Previous studies have shown that platelets are involved in the inflammatory process. Mean platelet volume (MPV) has been frequently used as an inflammatory marker in various diseases associated with inflammation. The role of MPV in children with chronic spontaneous urticaria (CU), however, has not yet been evaluated. In this study we compared MPV levels between children with and without CU.

MethodsChildren with CU and age-matched healthy children were enrolled in the study. Complete blood count and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were assessed in children with CU whilst MPV levels were compared between children with and without CU.

ResultsForty children with CU (19 males; mean age: 8.0±3.8 year; range: 3–15 years) and 40 healthy children (17 males; mean age: 6.9±3.0 year; range: 2–14 year) were enrolled on the prospective, case-control study. MPV (fL) levels were significantly lower in children with CU when compared to healthy children (7.42±0.77 and 7.89±0.65, respectively; p=0.004). Both mean platelet number and median CRP levels were significantly higher in children with CU when compared to healthy children (p=0.008, p=0.014, respectively).

ConclusionTo our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate the role of MPV as an inflammatory marker in children with CU. A decline in MPV may be considered as an indicator of inflammation in children with CU.

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CU) is defined by urticarial symptoms which last for six or more weeks. CU is usually observed following an inflammatory response mediated by mast cells. Its prevalence is reported to be around 0.6% in adults. In children, however, chronic urticaria is less common and has been reported to affect 0.1–0.3% of all children.1,2 Although the etiology of chronic urticaria is usually considered idiopathic, acute and chronic infections, as well as food and drug hypersensitivity reactions and autoimmunity are recognized as potential etiologic factors.3

Platelets are implicated in the pathogenesis of CU inflammation.4 While the number of platelets increases during inflammation, their volume tends to decrease or increase.5,6 The role of mean platelet volume (MPV) as an inflammatory marker has been previously demonstrated in various diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), acute rheumatic fever (ARF), familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) and cystic fibrosis (CF).7–11 Studies assessing the association of CU and MPV in adults, however, are limited. Indeed, to our knowledge, there are, as yet, no published data showing this association in children. In the current study we sought to assess MPV levels in children with CU and to compare them with healthy controls.

Materials and methodsStudy populationIn this study, we prospectively enrolled children who have presenting to the pediatric allergy outpatient clinic of Fatih University due to CU between January 2012 and February 2013. CU, based on the current guidelines, was defined as urticarial symptoms lasting for six or more weeks. Children with physical urticaria and other types of chronic urticaria were excluded.3 Age and sex-matched healthy children who presenting to the outpatient clinic for regular control visits were enrolled on the control group. Complete blood counts and CRP (C reactive protein) levels were investigated for both groups and MPV levels were compared between the two groups.

Venous blood samples were collected in Vacuette tubes (Greiner Bio-One, Monroe, North Carolina). A Complete blood count analyses were performed using the LH-780 system (Beckman Coulter Diagnostics, Image 8000, Brea, CA, USA). CRP levels (normal range:0–8mg/dL) were measured by way of the turbidimetric assay method using a Roche P 800 modular system (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Serum IgE levels were measured with the ECLIA (Electrochemiluminescence) method using the ELX-800 system (DIAsource, Nivelles, Belgium). We assessed atopy using the skin prick test (SPT) and specific IgE (sIgE) measurements. We defined a positive SPT test as a wheal with a mean diameter of at least 3mm greater than that of a saline control. Each child was tested with a core battery of allergens (e.g. dust mite, cockroach, cat, dog, mold, grass, tree, weed, milk, egg, peanut) and a clinic-specific battery of locally relevant allergens (ALK Abelló, Hørsholm, Denmark).

Statistical analysisStatistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPPS) for Windows, version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). We expressed categorical variables as percentages and continuous variables as mean±standard deviation (SD). We used the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test to evaluate whether the distribution of continuous variables was normal. We used the Chi-square test to analyze categorical variables, whilst the student t-test was used for continuous variables with normal distribution, and the Mann–Whitney U test was used for continuous variables which did not exhibit normal distribution. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. For all possible multiple comparisons, the Bonferroni Correction was applied for controlling Type I error. The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of Fatih University Medical School.

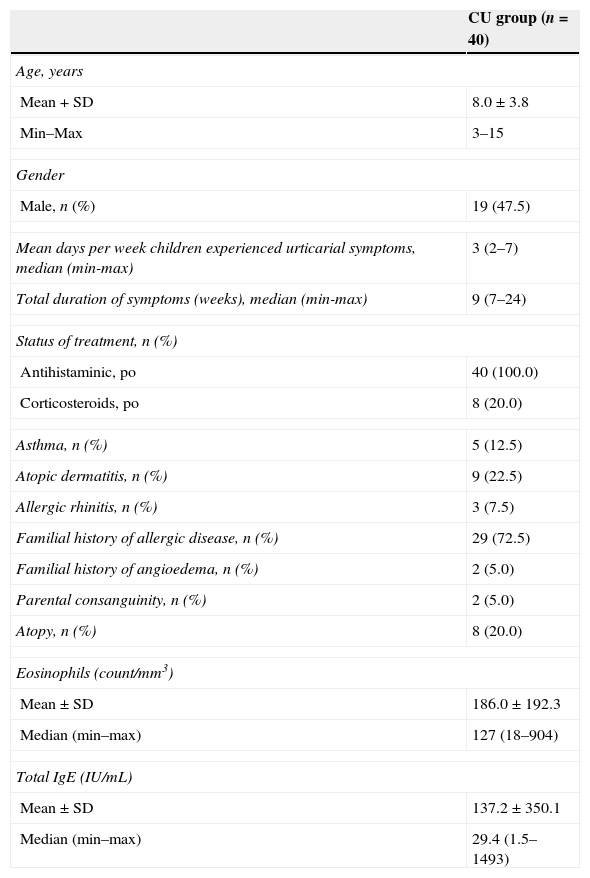

ResultsForty consecutive children with CU (19 males; mean age: 8.0±3.8 year; age range: 3–15 year) were enrolled in the study group and 40 healthy children (17 males; mean age: 6.9±3.0 year; age range: 2–14 year) in the control group. The two groups were well matched in terms of mean age and gender (p>0.05). The demographic characteristics of children with CU are presented in Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of children with CU.

| CU group (n=40) | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| Mean+SD | 8.0±3.8 |

| Min–Max | 3–15 |

| Gender | |

| Male, n (%) | 19 (47.5) |

| Mean days per week children experienced urticarial symptoms, median (min-max) | 3 (2–7) |

| Total duration of symptoms (weeks), median (min-max) | 9 (7–24) |

| Status of treatment, n (%) | |

| Antihistaminic, po | 40 (100.0) |

| Corticosteroids, po | 8 (20.0) |

| Asthma, n (%) | 5 (12.5) |

| Atopic dermatitis, n (%) | 9 (22.5) |

| Allergic rhinitis, n (%) | 3 (7.5) |

| Familial history of allergic disease, n (%) | 29 (72.5) |

| Familial history of angioedema, n (%) | 2 (5.0) |

| Parental consanguinity, n (%) | 2 (5.0) |

| Atopy, n (%) | 8 (20.0) |

| Eosinophils (count/mm3) | |

| Mean±SD | 186.0±192.3 |

| Median (min–max) | 127 (18–904) |

| Total IgE (IU/mL) | |

| Mean±SD | 137.2±350.1 |

| Median (min–max) | 29.4 (1.5–1493) |

IgE, immunoglobulin E; CU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; SD, standard deviation.

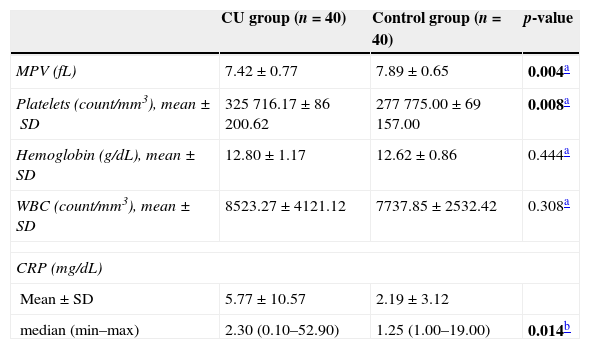

MPV (fL) levels in the CU group were significantly lower than those in the control group (7.42±0.77 and 7.89±0.65, respectively; p=0.004). Platelet count was, though not clinically significant, higher in the study group when compared to the control group (p=0.008). Mean hemoglobin and WBC levels were similar between groups (p>0.05). Median CRP (mg/dL) levels were significantly higher in children with CU when compared to healthy children (2.30 and 1.25, respectively; p=0.014). Comparative laboratory values for the study group are presented in Table 2.

The laboratory characteristics of the CU and control groups.

| CU group (n=40) | Control group (n=40) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MPV (fL) | 7.42±0.77 | 7.89±0.65 | 0.004a |

| Platelets (count/mm3), mean±SD | 325716.17±86200.62 | 277775.00±69157.00 | 0.008a |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL), mean±SD | 12.80±1.17 | 12.62±0.86 | 0.444a |

| WBC (count/mm3), mean±SD | 8523.27±4121.12 | 7737.85±2532.42 | 0.308a |

| CRP (mg/dL) | |||

| Mean±SD | 5.77±10.57 | 2.19±3.12 | |

| median (min–max) | 2.30 (0.10–52.90) | 1.25 (1.00–19.00) | 0.014b |

CU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; CRP, C reactive protein; MPV, mean platelet volume; WBC; white blood cells.

Although various infectious and autoimmune disorders as well as certain food and drug hypersensitivity reactions are known to predispose to CU, the etiology for the majority of children with CU is unknown. CU is usually observed following the release of histamine and other mediators from activated mast cells. The persistence of urticaria beyond six months results in chronic skin inflammation. Previous studies have shown that disease activity is associated with an increase in several inflammatory markers such as CRP and interleukin-6 (IL-6).12,13 Furthermore, several authors have claimed that CRP could be used as an indicator of disease activity in patients with CU.14 The role of platelets in immune-inflammatory processes is well established. Kasperska-Zajac et al.15 showed that platelet factor 4 (PF-4), beta-thromboglobulin (beta-TG), chemokine levels displayed an increase in patients with delayed pressure urticaria, a subtype of chronic urticaria. In addition, platelets are implicated in the pathogenesis of diverse, inflammation-driven skin diseases such as urticaria, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis.4,16,17

In our study, the fact that CRP levels and platelet counts were higher in children with CU when compared to healthy children supports the view that these patients have chronic inflammation. Indeed, previous studies reported an increase in CRP levels in patients with CU.18 We found significantly lower MPV levels in children with CU when compared to healthy children. We also demonstrated that platelets are affected by the mast cell driven inflammatory process,4,19 resulting in a decline in their mean volume levels. In view of these results, we suggest that MPV may be used as a potential marker of inflammation in children with CU. Besides, we also believe that strategies incorporating platelets in the treatment of the disease could be promising.

Studies assessing the role of MPV as an inflammatory marker in adults with chronic urticaria are scarce. However, Confino-Cohen et al.,20 using a large case series of patients with chronic urticaria, demonstrated that the prevalence of auto-immune disorders in these particular group of patients was high and that mean MPV levels were increased. Magen et al.18 after assigning 373 patients to either the autologous serum skin test (ASST) positive or negative groups, demonstrated that ASST-positive patients had higher mean MPV levels. Also, they also showed that MPV levels correlated with disease severity in ASST-positive patients with chronic urticaria. In another study, Magen et al.21 found higher CRP and MPV levels in CU patients resistant to antihistamines. All of these studies confirm the view that inflammation is implicated in the pathogenesis of chronic urticaria and that MPV plays an important role in this process. Nevertheless, the role of MPV as an inflammatory marker in children with CU has not yet been studied. In the present study, we found that MPV, in contrast to adult studies, was lower in children with CU when compared to healthy children. These results are in accordance with previous studies which showed decreased MPV levels in children with various inflammatory diseases. Sert et al.11 demonstrated that erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and CRP levels increased and that MPV levels decreased in patients with ARF due to the inflammatory process. Moreover, Makay et al.8 reported that MPV levels were lower during both the acute and disease-free period of children with FMF when compared to healthy children. Uysal et al.10 found that patients with cystic fibrosis had lower MPV levels during disease exacerbation when compared to healthy controls and the attack-free period.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, data pertaining to MPV levels in the remission state are missing. Secondly, we did not assess the urticaria severity scores of the patients; hence we were unable to evaluate the correlation between MPV levels and urticaria severity. The disease severity scale is actually used in adult patients3 and is not validated for use with children.1

In conclusion, to our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the role of MPV as an inflammatory marker in children with CU. We found that MPV levels were significantly lower in children with CU than in healthy children. Our study suggests the view that inflammation is implicated in the pathogenesis of chronic urticaria and that MPV plays an important role in this process.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Gulsen Mutluoglu for her sincere contributions in translation of this article.