Hepatitis B virus (HBV) has been classified into 8 genotypes (A-H). Genotypes A, D and F have been identified in some South American countries, but in Venezuela studies have been more restricted to aboriginal communities where genotype F is predominant. The aim of the present study was to identify the prevalence of HBV genotypes among native HBsAg carriers in Venezuelan urban areas. In addition, we correlated the predominant HBV genotype with epidemiological, serological and virological features of the infection. Non-Venezuelan migrant patients were excluded from this study. Serum samples from 90 patients (21 children and 69 adults) with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) were analyzed. Seventy-four patients had CHB e-antigen positive and 16 CHB e-antigen negative. HBV DNA serum levels of the whole group ranged from 4.1 to 8.8 log1H IU/mL. Patients with CHB e-antigen positive showed significantly higher viral loads (P = 0.0001) than the group with CHB e-antigen negative. Eighty-eight patients (97.8%) exhibited HBV genotype F while two non-related patients (2.2%) were infected with A + F genotypes. Genotype F is the main circulating HBV strain among HBsAg carriers from Venezuelan urban areas. This genotype is associated mostly with CHB e-antigen positive and high rate of transmission. Progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma could be major clinical events of this patient population independently of age at acquisition or transmission route.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) has been classified into 8 genotypes (A-H) by means of molecular evolutionary genetics analysis.1 There is growing evidence that HBV genotypes may influence the natural history of liver disease including mode of transmission, disease progression, seroconversion to HBe antibody, presence of HBV mutants and response to therapy.2 Today, the application of nucleic acid tests for clinical management of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is almost mandatory.3 This battery of tests includes measurement of viral load and genotyping of emergent resistant viral mutants during therapy.3 Moreover, in countries with high prevalence of HBsAg chronic carriers, HBV genotyping has been introduced as valuable test in the clinical management of CHB.4

Epidemiological data suggest that 7 to 12 million Latin Americans are infected with hepatitis B virus.5 Currently in Venezuela, the mean morbidity rate of HBV is approximately 3.8 x 100.000 inhabitants. Moreover, Venezuela is classified as having an intermediate prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in urban areas.6,7 Venezuelan aborigine population is categorized as having the highest rate of HBsAg,6,7 and HBV genotype F has been well-documented as the most prevalent.7 However, there is scarce data regarding HBV genotypes in HBsAg chronic carriers from Venezuelan urban populations. The present study was designed to identify the prevalence of HBV genotypes in native HBsAg chronic carriers in Venezuelan urban areas. In addition, we correlated the predominant HBV genotype with epidemiological, serological and virological features of the HBV infection.

Subjects and MethodsPatient populationThis study was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant. Patients with chronic HBV infection from different urban Venezuelan cities and referred to our tertiary diagnostic center (Intediag-HV, Caracas) were recruited into this study. Patients were not on treatment at the time of the investigation. Non-Venezuelan migrant patients were excluded from the study. Serum samples from each patient were collected, aliquoted and stored at-20 °C until analysis.

Serological and virological testsHepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) and antibodies (anti-HBe) were determined using the Axsym™ immunoassay system (Abbott Laboratories; Chicago, IL, USA). HBV DNA serum levels were measured by real-time PCR (Real-Art® HBV PCR assay, (Artus-Biotech, Qiagen, Hamburg, Germany)8-10 HBV genotypes were identified by PCR using type-specific primers in accordance to a commercial assay (Human Hepatitis B Virus Genotyping, Genekam Biote-chnology AG, Duisburg, Germany).11 Briefly, a nested PCR is carried-out based on differences in the conserved nucleotides in the envelope ORFs followed by a second PCR using two mixes of primers (group 1: A 68 bp, B 281 bp, C 122 bp; group 2: D 119 bp, E 167 bp, F 97 bp) to differentiate the HBV genotypes based on amplicon length.

Statistical analysisViral loads data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). In all cases, the Kolmogorov-

Smirnov test was applied to test for normal distribution (Graphpad Instant software for Window version 305). Unpaired Student t test was employed to compare differences in means of viral load levels between the e-antigen positive and the e-antigen negative HBsAg chronic carriers. The significance level was assessed at p < 0.05.

ResultsPatient populationOur study population comprised of 90 patients with chronic HBV infection from different Venezuelan urban cities. Patients were classified in two groups. Group A consisted of 21 children and adolescents (mean age 10 ± 6 years, 11 males and 10 females). The majority of patients were in the immune-tolerant phase of the infection and showing normal values of alanine-aminotransferase (ALT). Only two patients have mild elevation of ALT. Patients acquired HBV either via blood transfusion or health-care measures during chemotherapy. Group B comprised of 69 adults (mean age 46 ± 12 years, 36 males and 33 females), and they presented elevations (> 2.5 fold normal value) or fluctuations of ALT values. They mainly acquired HBV by sexual contact.

HBeAg and anti-HBeAll patients from group A were e-antigen positive. In group B, 53 patients showed e-antigen positive and 16 patients presented e-antigen negative with positive anti-HBe antibodies. Overall, 74 patients (82.2%) showed CHB e-antigen positive and 16 patients (17.8%) CHB e-antigen negative.

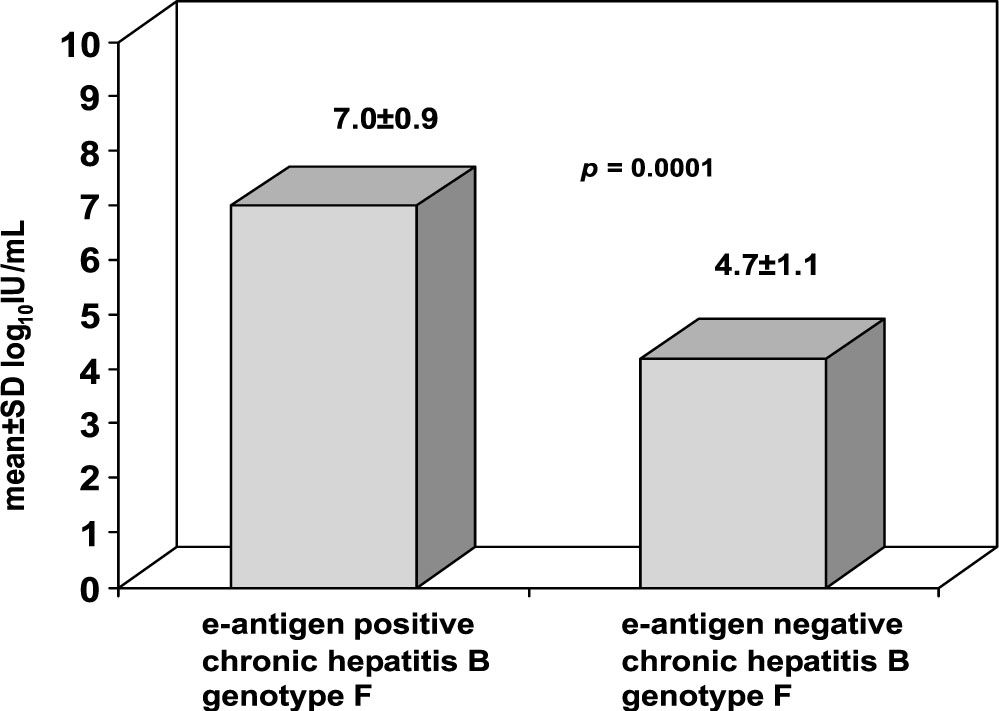

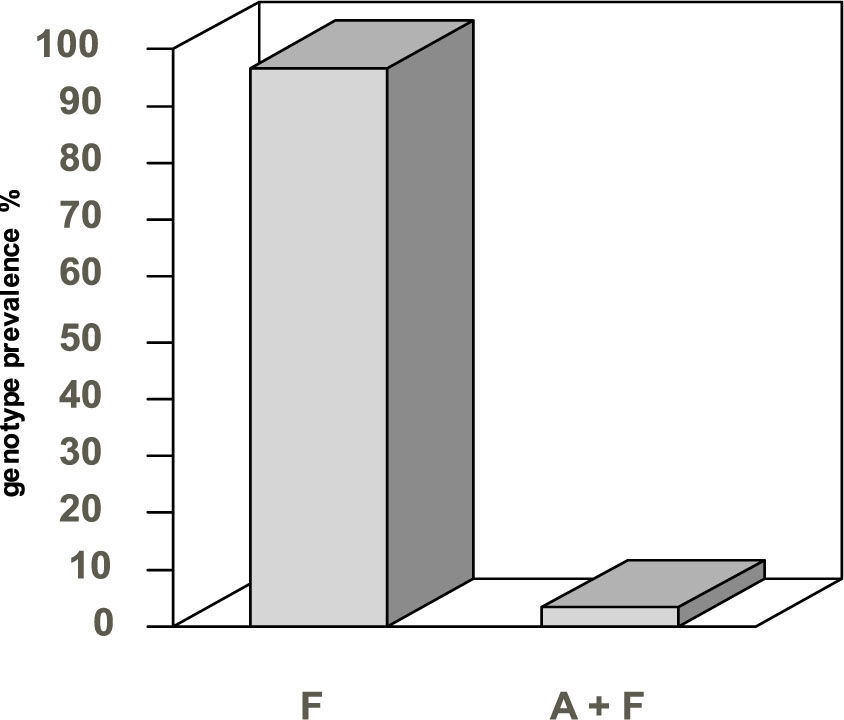

HBV DNA circulating viral load and HBV genotypesThe whole group showed HBV DNA levels ranging from 4.1 to 8.8 log10 IU/mL. No difference in viral load was found between groups A and B patient e-antigen positive. However, HBV DNA levels were significantly higher (P = 0.0001) in CHB patients with e-antigen positive compared with those with CHB e-antigen negative (see Figure 1). Genotype F hepatitis B predominated in 88 patients (97.8%). Only two non-related patients (child and adult), both with CHB e-antigen positive, showed to be co-infected with genotype A and genotype F hepatitis B (Figure 2).

HBV DNA viral loads shown by the group of urban patients with CHB, genotype F, e-antigen positive and e-antigen negative. HBV DNA levels expressed as log10 IU/mL, were significantly higher (P = 0.0001) in 74 patients with CHB e-antigen positive compared to 16 patients with CHB e-antigen negative.

We have demonstrated that HBV genotype F prevails in Venezuelan urban populations infected with hepatitis B virus regardless of the immune status of patients. This genotype was identified in either CHB e-antigen positive or e-antigen negative cases. Moreover, HBV genotype F was observed in patients who acquired the infection by different modes of transmission (sexual, blood transfusion, chemotherapy). Only two patients, both in the active phase of the disease, were co-infected with genotypes A and F.

HBV genotype F prevails in Amerindians from Western and Southern Venezuela.7 In addition, the circulation of this genotype has been reported in other communities such as hemodialysis patients and few patients with chronic hepatitis B.12 Our results are in good agreement with previously repor-ted data in South America. Indeed, genotype F has been predominantly found in groups of HBV patients from Colombia (Venezuela’s eastern-border country),13 but differs from those observed in Brazil (Venezuela’s southern border country) where the frequency of genotype F is lower even in northern areas of this country.14 This disparity could be related to differences in the ethnic origins of Brazilian inhabitants. Unlike the Venezuelan hybrid mestizo population (Mongoloid, Negroid and Caucasian), the Native Amerindian inhabitants have only made a minor contribution to the Brazilian population as a whole,14,15 We have now envisaged future genoty-ping studies including non-Venezuelan migrant HBV patients to determine whether this population exhibits a different genotype pattern. Interestingly, we thus far have identified two patients with genotype F and one with genotype F C C among five HBV carrier immigrants from China. This suggests a high grade of circulation and transmission of genotype F among our urban populations.

Based on previous reports, HBV genotype A has been associated to CHB e-antigen positive while genotypes B, C and D (often present precore mutants) are serologically associated with positive anti-HBe antibodies.3,4 One of few published articles on HBV infection and genotype F documented that this pa-tient population, who were all HBeAg positive, had the lowest rate of remission.16 Furthermore, the proportion of patients who presented with hepatic decompensation or died were higher than those infected with genotype A or D. In addition, none of these subjects cleared HBsAg from the serum. We have previously reported that over 60% of our adults HBV carriers have the presence of anti-HBe antibodies but they are clinically in inactive state.17-20 In addition, more than 80% of patients with active disease presented CHB e-antigen positive and 12% to 18% CHB e-antigen negative.19,20 In the present study, we also found that 82% of patients had CHB e-antigen positive and significantly higher viral load. Taken together, although these results demonstrate that genotype F is mainly associated with CHB e-an-tigen positive, we have to be aware that an important segment of our HBsAg carriers with positive anti-HBe antibodies might represent CHB e-antigen negative instead of inactive HBV carrier state. Therefore, we have to make the effort to quantify HBV-DNA levels to assess the appropriate diagnosis and management of these patients.21,22

A recently published study among Alaska Native young populations infected with HBV demonstrated that genotype F strain compared to genotypes A, B, C or D was significantly associated with the occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).23 The incidence of HBV-induced HCC has not been accurately established in our country. However, Leon, et αl. reported that over a 8-year period they had diagnosed 14 patients infected with HBV (40-50 years old) who developed HCC, twelve of them already with liver cirrhosis and two without.20 Another study compiling 68 Venezuelan patients with HCC, most of them in the sixth decade of life, described HBV as the main etiologic agent in 347 of cases.24 The development of cirrhosis and liver cancer during the fourth and sixth decade of life has also been described in other Latin American countries, where HBV transmission occurs primarily from sexual contact like in Venezuelan urban areas.25,26 On the other hand, the progress to chronic liver disease and HCC in Asian HBV carriers, who have acquired the infection perinatally, occurs early in childhood.27 In Venezuela, these complications in HBV-infected children have been described in four (10.2 7) out of thirty nine children over a 9-year follow-up.28 However, they acquired the infection during chemotherapy rather than perinatally. This finding is not surprising since nosocomial HBV infection in Venezuela remains a common unsolved problem nationwide from many decades ago.29,30 It is noteworthy to mention that thus far our children and adolescents with CHB do not seroconvert earlier to antiH-Be antibodies.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that genotype F is the main circulating HBV strain among HB-sAg carriers from Venezuelan urban areas. This genotype is associated mostly with CHB e-antigen positive and showed a high rate of transmission. Progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma could be major clinical events of this patient population independently of age at acquisition or transmission route. Longitudinal studies are encouraged to further describe the natural history of this disease in Venezuela.

Abbreviations- •

HBV: Hepatitis B Virus

- •

HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface Antigen

- •

CHB: Chronic hepatitis B

- •

HBeAg: Hepatitis B e antigen

- •

anti-HBe: Hepatitis Be antibody

- •

PCR: Polymerase Chain Reaction

- •

SD: Standard deviation

- •

HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma

This project was supported, in part, by an award to Intediag-HV granted by Fondo Pro-Salud 2007, Cámara Venezolana de Fabricantes de Cerveza (CAVEFACE), Venezuela. A preliminary report of this work was presented in an abstract form at the 13th International Symposium on Viral Hepatitis and Liver Disease, March, 2009, Washington, USA. www.ishld2009.org/pdf/ISVHLD_Poster_Presentation_Abstractspdf