Background. Transient elastography (TE) is a useful tool for the assessment of hepatic fibrosis as an alternative to liver biopsy, but it has not been validated as a screening procedure in apparently healthy people.

Aim. To determine the prevalence of advanced liver fibrosis diagnosed by TE in a socioeconomically challenged rural population.

Material and methods. We enrolled 299 participants aged over 18 years old from a vulnerable population in Mexico who responded to an open invitation. All participants had their history recorded and underwent a general clinical examination and a liver stiffness measurement, performed by a single operator according to international standards.

Results. Overall, 7.35% participants were found to be at high risk for cirrhosis. Three variables correlated with a risk for a TE measure ≥ 9 kPa and significant fibrosis: history of alcohol intake [7.95 vs. 92.04%, odds ratio (OR) 4.47, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.45-13.78, P = 0.0167], body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2 (30.87 vs. 69.12%, OR 4.25, 95%CI 1.04-6.10, P = 0.049), and history of diabetes mellitus (14.87 vs. 85.12%, OR 2.76, 95%CI 1.002-7.63, P = 0.0419). In the multivariate analyses BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 was the only significant risk factor for advanced liver fibrosis or cirrhosis (OR 2.54, 95%CI 1.02-6.3, P = 0.0460).

Conclusion. TE could be useful as a screening process to identify advanced liver fibrosis in the general and apparently healthy population.

Chronic liver diseases represent an important cause of morbidity and mortality in the Western world, affecting approximately 360 per 100 000 persons each year, and ranking as the twelfth leading overall cause of mortality, with about 800,000 deaths per year attributable to cirrhosis.1–3 Alcohol abuse, viruses and metabolic diseases are the most common causes of liver cirrhosis.4–6

Although the exact prevalence of cirrhosis worldwide is unknown, it is accepted that approximately 1% of the general population has histological cirrhosis.4 In Mexico, liver cirrhosis is the third highest cause of mortality in men and the seventh in women aged between 23 and 64 years. It is estimated that in Mexico there are 1.2 million people with hepatitis C (1.4% of the general population), 400,000-600,000 people with hepatitis B and three million alcohol addicts, all of whom have an increased risk of developing cirrhosis.5,7–9

Mexico is believed to have about 100,000 to 200,000 patients with cirrhosis, which is equivalent to 0.04-0.09% of the population,10 a seemingly low prevalence compared with that reported in other countries including the United States of America.11,12 These data could be an underestimation, as the high prevalence of undiagnosed cirrhosis in alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and hepatitis C infection is recognized. A similar prevalence has been reported in Europe, and numbers are even higher in most Asian and African countries where chronic viral hepatitis B or C are common.4 In Mexico it has been reported that liver cirrhosis mortality ranges from 11.6 to 47.4 per 100,000 inhabitants, with the highest mortality in the central area of the country.5,8,9

Most patients with chronic liver disease remain asymptomatic for a long period. Liver biopsy is considered an imperfect gold standard. Although it remains the best way to diagnose cirrhosis, it is by far too invasive and not acceptable for large-scale screening of populations.13 This is the rationale for developing noninvasive screening methods to detect advanced fibrosis or liver cirrhosis in the general population.

Currently there are two different approaches to assess fibrosis noninvasively: first, a biological approach based on the levels of serum biomarkers of fibrosis; and second, a physical approach based on liver stiffness measurement (LSM) using transient elastography (TE) (FibroScan®; Echosens, Paris, France). LSM has been correlated with the stages of hepatic fibrosis and has a good diagnostic accuracy for cirrhosis.14–17 Several studies have shown its utility in evaluating a general and apparently healthy population. Roulot, et al. demonstrated that in all individuals with LSM > 8 kPa, a cause of liver disease could be identified, conferring a positive predictive value for TE of 100% for cirrhosis diagnosed in 0.7% of the studied population.18

However, most of the studies screening for advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis have been performed in Caucasian populations in health-related facilities, and there is no information about vulnerable or indigenous populations in Latin America with a high risk of developing liver cirrhosis.19 The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of advanced liver fibrosis diagnosed by TE in socioeconomically challenged rural population of Tlapa de Comonfort Guerrero, Mexico which is a municipality in the southern of the state of Guerrero (Figure 1) that is characterized for vulnerable socioeconomic conditions. According to the last census of Mexican population realized in 2010, Tlapa de Comonfort recorded 65763 habitants of whom 31224 are men and 34539 women. It is a predominantly young population with a 53% of habitants under 20 years. The 48.5% of the population are indigenous, principally Nahuatl, Mixtec and Tlapanec.20

Material and MethodsThrough an open invitation to the adult population of Tlapa de Comonfort, 299 subjects were identified and underwent TE (FibroScan®; Echosens). Data were collected for clinical history, anthropometry, general physical examination and LSM. An interpreter explained the characteristics of the study to participants who did not speak Spanish. This study had been carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2008) of the World Medical Association, and has been approved by the Ethics Committee. All the participants accepted and gave written informed consent. Subjects with a previous diagnosis of cirrhosis or known chronic liver disease were excluded from this study.

The following data were collected: ethnicity (assessed by self-report and by the dialect recognized by the physicians and interpreter making the evaluation), age, sex, level of education (illiterate, elementary school, junior high school, high school, professional), occupation, history of blood transfusions, daily alcohol intake (numbers of glasses of alcohol per week) or previous history of excessive alcohol consumption for more than 10 years, tobacco use(number of cigarettes per day in a period of years) or history of wood smoke exposure (years of exposure), medical history (self-reported) or medication for hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease or dyslipidemia, type and duration of antidiabetic and antihypertensive treatments. The physical evaluation included vital signs, pulse rate, breath rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, body temperature, height, weight, body mass index (BMI) and hip and waist circumferences.

TE measurements are expressed in kilopascals (kPa), corresponding to the median value of 10 validated measurements, and range from 2.5 to 75 kPa.21 Based on previous data, participants were divided into three groups: low risk (< 7 kPa), intermediate risk (7-8.9 kPa) and high risk (≥ 9 kPa) for cirrhosis.18,22 LSM was performed with medium or extra-large sized probes, depending on the anthropometric characteristics of the subject, to obtain the best measurement. The measurements obtained were evaluated by interquartile range (IQR) and IQR/me-dian (M) ratio. We categorized the results as “very reliable” (IQR/M ≤ 0.10), “reliable” (0.10 < IQR/M ≤ 0.30, or IQR/M > 0.30 with LSE median < 7.1 kPa) and “poorly reliable” (IQR/M > 0.30 with LSE median ≥ 7.1 kPa).22

Continuous variables were described as mean and standard deviations; differences between means were analyzed using Student’s t test or the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables are described as numbers and percentages; differences between proportions were analyzed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. To identify risk factors associated with advanced fibrosis, multivariate unconditional logistic regression analyses were conducted. Multicollinearity in the adjusted models was tested by deriving the covariance matrix. A P-value < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using the statistics program SPSS (version 12.0; IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA).

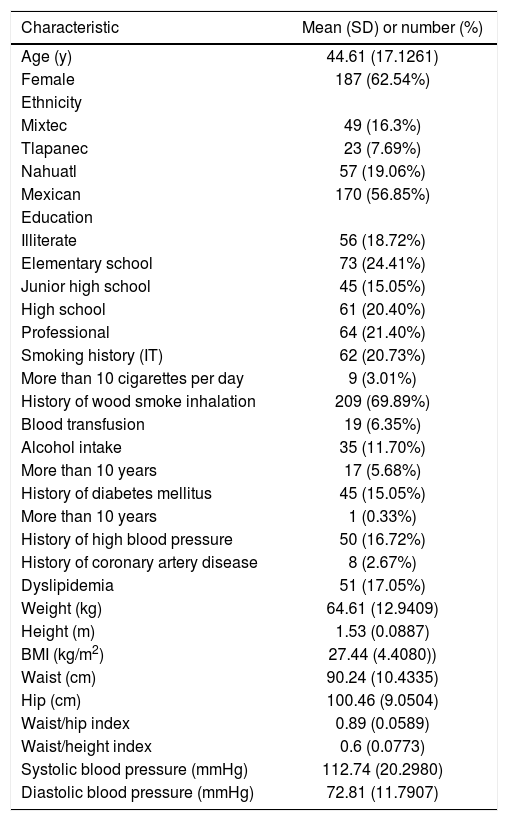

ResultsAt the end of the call for participants, 299 people had been evaluated. Their mean age was 44 ± 17 years, the majority were women (62.5%). More than half (56.8%) were not indigenous; Nahuatl (19.1%) and Mixtec (16.3%) were the two most frequent ethnicities followed by Tlapanec (7.6%). With respect to educational level, 18.7% were illiterate, elementary school was the most frequent educational level (24.4%) and high school and professional levels were the second and third in frequency with 20.4% and 21.4%, respectively. The main occupations were housewife (29.4%), general employee (14.4%) and farmer (13.4%), with only 3.01% of participants reporting being unemployed. A history of cigarette smoking was reported by 20.73%, but only 3.01% reported smoking more than 10 cigarettes per day. A history of wood smoke inhalation was reported by 69.9%. A history of blood transfusion history was reported by 6.3% of the population. Alcohol intake was reported by 11.70 and 5.68% reported alcohol consumption for more than 10 years (Table 1).

Main clinical characteristics of the population.

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) or number (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 44.61 (17.1261) |

| Female | 187 (62.54%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Mixtec | 49 (16.3%) |

| Tlapanec | 23 (7.69%) |

| Nahuatl | 57 (19.06%) |

| Mexican | 170 (56.85%) |

| Education | |

| Illiterate | 56 (18.72%) |

| Elementary school | 73 (24.41%) |

| Junior high school | 45 (15.05%) |

| High school | 61 (20.40%) |

| Professional | 64 (21.40%) |

| Smoking history (IT) | 62 (20.73%) |

| More than 10 cigarettes per day | 9 (3.01%) |

| History of wood smoke inhalation | 209 (69.89%) |

| Blood transfusion | 19 (6.35%) |

| Alcohol intake | 35 (11.70%) |

| More than 10 years | 17 (5.68%) |

| History of diabetes mellitus | 45 (15.05%) |

| More than 10 years | 1 (0.33%) |

| History of high blood pressure | 50 (16.72%) |

| History of coronary artery disease | 8 (2.67%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 51 (17.05%) |

| Weight (kg) | 64.61 (12.9409) |

| Height (m) | 1.53 (0.0887) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.44 (4.4080)) |

| Waist (cm) | 90.24 (10.4335) |

| Hip (cm) | 100.46 (9.0504) |

| Waist/hip index | 0.89 (0.0589) |

| Waist/height index | 0.6 (0.0773) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 112.74 (20.2980) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 72.81 (11.7907) |

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus was 15%, but only one person reported disease duration of more than 10 years. High blood pressure was observed in 50 participants (16.7%), a history of coronary artery disease identified as acute myocardial infarction was present in 2.67%, dyslipidemia in 17.1% and retinopathy in only one person. According to the World Health Organization BMI categories, our participant population was distributed as underweight, two participants (0.7%), normal weight, 102 participants (34.1%), overweight, 138 participants (46.2%) and obese, 63 participants (21.1%).Of the obese participants, 50 (16.7%) were classified with grade 1 obesity, 11 (3.7%) as grade 2 obesity, and only two (0.7%) with grade 3 obesity.

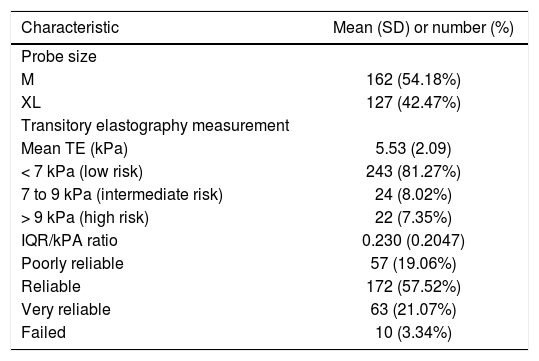

The mean BMI of participants was 27.34 ± 4.41 kg/m2, the mean waist/hip index was 0.89 ± 0.05 and the mean waist/height index was 0.6 ± 0.0773. The mean systolic blood pressure was 112.7 ± 20.3 mmHg and the mean diastolic blood pressure was 72.8 ± 11.8 mmHg (Table 1). For TE, a medium probe was used in 162 subjects and an extra-large probe in 127 subjects, 54.2% and 42.5%, respectively. Measurement failed in 10 subjects, representing 3.34% of the studied population (Table 2).

Transitory elastography characteristics.

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) or number (%) |

|---|---|

| Probe size | |

| M | 162 (54.18%) |

| XL | 127 (42.47%) |

| Transitory elastography measurement | |

| Mean TE (kPa) | 5.53 (2.09) |

| < 7 kPa (low risk) | 243 (81.27%) |

| 7 to 9 kPa (intermediate risk) | 24 (8.02%) |

| > 9 kPa (high risk) | 22 (7.35%) |

| IQR/kPA ratio | 0.230 (0.2047) |

| Poorly reliable | 57 (19.06%) |

| Reliable | 172 (57.52%) |

| Very reliable | 63 (21.07%) |

| Failed | 10 (3.34%) |

The majority of the participants (81.27%, 243 participants) were in the low-risk group for cirrhosis; the intermediate-risk group included 24 participants (8.02%) and the high-risk group included 22 participants (7.35%), including 11 males and 11 females. The quality of the LSM was “reliable” (172 subjects, 57.52%) or “very reliable” (63 subjects, 21.07%) in most participants, and only 19.06% (57 participants) had “poorly reliable” results (Table 2). Ten (3.34%) participants with measurement failure were excluded from statistical analyses.

Three variables correlated with risk for TE ≥ 9 kPa: history of alcohol intake (odds ratio (OR) 4.47, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.45-13.78, P = 0.0167), BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 (OR 4.25, 95% CI 1.04-6.10, P = 0.049), and history of diabetes mellitus (OR 2.76, 95% CI 1.002-7.63, P = 0.0419) (Table 3).

Risk factors for liver cirrhosis (transitory elastography ≥ 9 kPa).

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | |||

| Elementary schooling | 2.38 | 0.97-5.85 | 0.051 |

| Indigenous | 0.75 | 0.30-1.86 | 0.6544 |

| Alcohol intake | 4.47 | 1.45-13.78 | 0.0167 |

| Transfusion | 1.76 | 0.37-8.39 | 0.359 |

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 2.53 | 1.04-6.10 | 0.049 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.76 | 1.002-7.63 | 0.0419 |

| Multivariate | |||

| Alcohol intake | 1.64 | 0.65-4.15 | 0.291 |

| Transfusion | 1.39 | 0.27-7.24 | 0.689 |

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 2.53 | 1.02-6.32 | 0.046 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.55 | 0.89-7.34 | 0.081 |

In the multivariate analyses adjusted for history of alcohol intake, history of diabetes mellitus, BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, transfusion history and educational level, BMI > 30 kg/m2 was the only significant risk factor for advanced liver fibrosis (OR 2.54, 95% CI 1.02-6.33, P = 0.0460) (Table 3).

DiscussionLiver cirrhosis is the twelfth leading cause of death in the Western world, accounting for more than 800,000 deaths per year. In developing countries such as Mexico, many programs designed to detect disease do not operate in areas with limited accessibility because their geographical location makes it difficult for their inhabitants to access health care systems. We considered it necessary to make an assessment of this type of population in Tlapa de Comonfort, Guerrero, Mexico, in a population that is almost half (48.56%) of indigenous origin and young (53.3% aged less than 20 years old), using a noninvasive and simple procedure such as TE.

We studied 299 subjects (just 0.45% of the population of the town) and found a prevalence of cirrhosis of 7.35% with no sex predominance. The main risk factor for advanced fibrosis in the adjusted multivariate analysis was BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, which is consistent with the current trend of increasing nonalcoholic steatohepatitis as a major cause of chronic liver disease.23 The mean BMI in our population was higher (27.44 kg/m2) compared with other studied populations. For example, Liu, et al. in 2010 described a study in women in the UK from 1996 to 2001, in which a BMI of 22.5 kg/m2 or above was associated with an increased incidence of liver cirrhosis. In that study, the adjusted relative risk of liver cirrhosis increased by 28% (relative risk 1.28, 95% CI 1.19-1.38, P < 0.001) for every 5-unit increase in BMI.24 The level of education (mainly elementary school) or ethnicity was not considered in this British population.25,26

We found a prevalence for TE results compatible with cirrhosis of 7.35%, which is similar to that found in other studies such as that performed by Roulot, et al. in Bobigny, France, which found a prevalence of cirrhosis of 8%.

We obtained better performance with the LSM procedure compared with other series,18 with only 10 participants in whom measurement failed (3.34%). However, unreliable LSM results were obtained in 19.1% of participants (n = 57), which is higher than the 7.1% reported by Roulot, et al.

Chronic diseases and poverty are related. Poor people are more vulnerable for several reasons, including greater exposure to risks including use of tobacco products, consumption of energy-dense and high-fat food, being physically inactive and overweight or obese, and decreased access to health services. In all countries, poor people are more likely to die after developing a chronic disease. In middle- and high-income countries, the poor tend to be more obese than the wealthy, which has been viewed as something of a paradox.27 In Latin America, especially in low- and middle-income countries like Mexico, the mean population BMI is 27 kg/m2, overweight and obesity (BMI ≥ 25) is observed in 65% of the population and 26% of the Mexican population is obese (BMI ≥ 30).27

It is projected that the number of deaths worldwide in 2030 because of non-communicable diseases in lower-middle income countries will increase from 13 million in 2005 to nearly 19 million,28 so cirrhosis will be one of the most preventable diseases causing death around the globe.

The main limitations of the present study are the missing blood laboratory results because of the difficulty of access to the study location, difficulties maintaining all the samples in good condition for processing in an established laboratory, and that only those subjects who answered the invitation to participate were evaluated.

In conclusion, the assessment of advanced fibrosis by TE in a population with a socioeconomic profile different from the general or health-system-related population shows a higher prevalence of advanced fibrosis than is evident in the available data from Mexico. Obesity is considered an independent risk factor for advanced fibrosis in this population. Further research is needed to establish preventive measures in this vulnerable population.

Abbreviations- •

BMI: body mass index.

- •

IQR: interquartile range.

- •

kPa: kilopascals.

- •

LSM: liver stiffness measurement.

- •

M: median.

- •

TE: transient elastography.

None.

AcknowledgmentsThe authors would like to thank the Medicine & Social Assistance Foundation for use of their facilities for patient evaluation.