Introduction. Liver metastases (LM) are crucial prognostic manifestation of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST). With the advent of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI), management of metastatic GIST has radically changed. Long clinical follow-up provides an increased proportion of GIST patients with LM who are candidates for potentially curative therapy.

Material and methods. Patients who underwent treatment for liver metastases of GIST between 2000-2009 in our department were included in the study. Mean follow-up was 84 months (range 40-145) months. In retrospective analysis we investigated clinical, macro-/microscopic and immunohistochemical criteria, surgical, interventional and TKI therapy as well.

Results. In 87 GIST-patients we identified 25 (29%) patients with metastatic disease. Of these, 12 patients (14%) suffered from LM with a mean age of 60.5 (range, 35-75) years. Primary GIST were located at stomach (n = 4, 33%) or small intestine (n = 8, 67%); all of them expressed CD117 and/or CD34. LM were multiple (83%), distributed in both lobes (67%). They were detected synchronously with primary tumor in 33% and metachronously in 77%. All patients with liver involvement were considered to treatment with TKI. LM were resected (R0) in 4 patients (33%). In recurrent (2/4) and TKI resistant cases, interventional treatment (radiofrequency ablation) and TKI escalation were carried out. During a median follow-up of 84 months (range 30-152), 2 patients died (16.5%) for progressive disease and one patient for other reasons. Nine patients (75%) were alive.

Conclusion. Treatment of LM from GIST needs a multimodal approach. TKI-therapy is required at any case. In case of respectability, surgery must be carried out. In unresectable cases or recurrent/progressive disease, interventional treatment or TKI escalation should be considered. Therefore, these patients need to be treated in experienced centres, where multimodal approaches are established.

Before the advent of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI), surgical resection was the only curative treatment of primary gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST). Nowadays the specific molecular target therapy is revolutionary in the treatment of both primary and metastatic GIST, changing the role of surgery in the management of these patients.1 Liver metastases and/or peritoneal dissemination are the usual main prognostic relevant metastatic manifestations of GIST.1,2 Up to 72% present to have a liver involvement.3,4 Controversy exists in the clinical management of the hepatic metastases.

Resection of liver metastases arising from neuroendocrine or colorectal carcinoma is a well-established and effective treatment modality with reported 5-year survival rates of 30% to 76% in patients with liver-only disease.5–7 In contrast, the role of hepatic surgery for GIST metastasis to liver remains still undefined. Before the TKI era, liver metastases had to be resected but unfortunately the outcome was still rather poor and the patients could only achieve a 5-year overall survival of 27% to 34% after the surgical resection.8,9 But most studies on liver metastasis of GIST are retrospective and limited by small patient numbers,10,11 including other sarcoma subtypes in addition to GIST8–10,12 or short median follow-up.13,14 Some other interventional therapeutic possibilties for hepatic metastatic lesions of GIST, such as radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE), have been published in case reports.15–21 But it remains still undefined which treatment modality should be used in which clinical scenario and the role of TKI therapy during these procedures is not completely clarified.

In this study we present our experience with the management of liver metastases from GIST and we attempt to define the role of surgery and interventional procedures in the treatment of these patients given the emergence to the specific molecular approach in liver metastases from GIST.

Material and MethodsPatients and tumorsAt our institution, 87 patients with GIST were treated within a period of ten years (January 2000-December 2009). Our study encompassed those patients, who were identified with liver metastasis from GIST and underwent surgical or other treatment. The clinicopathological data of these patients and the date of last follow-up or death were collected from the sarcoma database of the Department of Surgery, University Hospital Erlangen and summarized in a retrospective analysis.

The diagnosis of GIST and their liver metastases was confirmed by experienced pathologist according to current criteria.1,21 A synchronous metastasis was defined as the detection of a liver metastasis during diagnosis of the primary tumor or within the first six months. Contrast-enhanced spiral computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and/or positron emission tomography (PET) were used to measure the target tumor every 3 months. The tumor response was assessed by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST)22,23 and modified CT response criteria (CHOI criteria)24 that assessed tumor density changes.

Recurrence was defined as any relapse of tumor either local or distant identified by imaging (MRI or CT) or verified by histological examination. Perioperative mortality was defined as death within the first 2 weeks after surgery. Morbidity included any complication, either surgical or non-surgical, and was rated according to Clavien’s classification with five severity grades.25 Last follow up was June 30th 2014 or death.

Treatment of liver metastasesA preoperative TKI therapy was performed in each case at an initial dose of 400 mg per day. Surgical therapy was performed when resectability was achieved, determined from radiological imaging which estimated the tumor response. The extent of surgery was specified by the estimated hepatic functional reserve. This was assessed by a combination of the preoperative liver biochemistry, the distribution of the metastatic lesions within the liver and the predicted remnant liver volume to maintain hepatic function after resection with the aim of achieving negative surgical margins. Resection was classified according to the Brisdan terminology.26 Postoperatively imatinib mesylate was administered at an initial dose of 400 mg per day. In case of tumor progression or recurrence, the dose level was upgraded to 600 mg or to maximal 800 mg per day. By persistent progression, the therapy was converted to sunitinib malate, nilotinib hydrochloride monohydrate or to sorafenib. Furthermore, in case of recurrence after surgical resection of LM a radiofrequency ablation of hepatic lesions was performed.

Histological and immunohistochemistry of GISTGIST diagnosis was verified according to current diagnosis criteria.21 Immunohistochemical staining was performed using antibodies against CD117, CD34, a-smooth muscle actin, desmin and protein S100. Mitoses were counted in 50 high-power fields. One high power field (HPF) corresponded to an area of 0.238 mm2. The risk category was defined by assessing the tumor size and mitotic count following the consensus guidelines of the National Institutes of Health-(NIH-NCI) workshop and the Miettinen’s criteria.18,21

ResultsPatient and tumor characteristics87 patients (M:F 52:35) were treated with GIST within ten years at our institution and 25 patients (29%) presented with metastatic disease. Twelve patients (14%) suffered from hepatic metastases. No patients in this study had a preoperative diagnosis of liver failure (e.g. cirrhosis). Median laboratory values for liver synthetic and secretory function were within normal range.

Patients who developed liver metastases suffered from primary tumors in the small intestine (67%) and in the stomach (33%), with a median tumor size of 12.75 cm. The majority of them (92%) were symptomatic (e.g. abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding, anemia) except for a case, where the tumor was detected within a routine work-up. In 5 cases the mitotic activity was low (< 5/50HPFs) and in 7 cases higher than 5/50HPFs. According to the classification of Fletcher,27 only one patient was classified as intermediate risk patient and eleven patients as high risk. According to the classification by Miettinen,21 on patient was classified to the low risk and eleven patients to the high risk group.

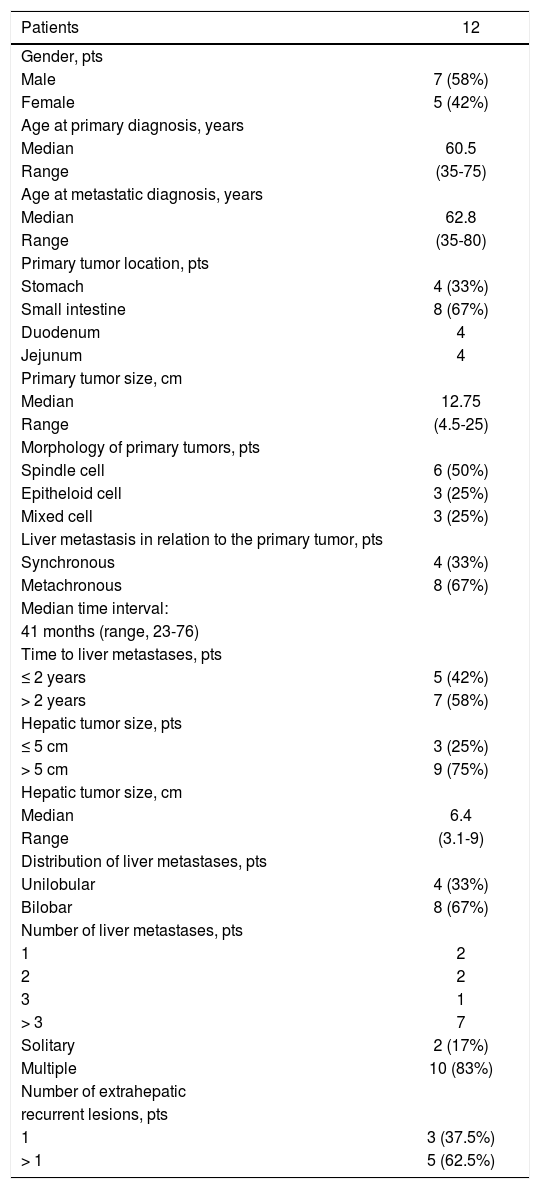

In 4 patients (33%) the liver metastases occurred synchronously with the primary tumor and in 8 cases (77%) metachronously, with a median time interval of 41 months (range, 23-76). The liver metastases were verified by MRI, CT or PET-CT (Figure 1). In four cases with unclear radiological findings, histopathological examination after CT guided needle biopsy was performed. In immunohis-tochemical analysis, all metastases presented typical morphology for GIST metastasis and KIT positivity. The clinical characteristics of primary tumors and of liver metastases are listed in table 1.

A. MR-enteroclysis: solitary liver metastasis (segment 6). B. Abdominal CT: GIST of the duodenum (yellow arrow) with synchronous liver metastasis (segment 4; white arrow) and cystic lesion (segment 6; red arrow). C and D. Abdominal CT: multiple hepatic metastatic disease of GIST. E. Abdominal PET-CT: bilobar liver metastase (segment 6 with contact with diaphragm, Standard Uptake Values-SUV max 6.7 and segment 2/3, SUV max. 7.6).

Characteristics of primary and metastatic tumors.

| Patients | 12 |

|---|---|

| Gender, pts | |

| Male | 7 (58%) |

| Female | 5 (42%) |

| Age at primary diagnosis, years | |

| Median | 60.5 |

| Range | (35-75) |

| Age at metastatic diagnosis, years | |

| Median | 62.8 |

| Range | (35-80) |

| Primary tumor location, pts | |

| Stomach | 4 (33%) |

| Small intestine | 8 (67%) |

| Duodenum | 4 |

| Jejunum | 4 |

| Primary tumor size, cm | |

| Median | 12.75 |

| Range | (4.5-25) |

| Morphology of primary tumors, pts | |

| Spindle cell | 6 (50%) |

| Epitheloid cell | 3 (25%) |

| Mixed cell | 3 (25%) |

| Liver metastasis in relation to the primary tumor, pts | |

| Synchronous | 4 (33%) |

| Metachronous | 8 (67%) |

| Median time interval: | |

| 41 months (range, 23-76) | |

| Time to liver metastases, pts | |

| ≤ 2 years | 5 (42%) |

| > 2 years | 7 (58%) |

| Hepatic tumor size, pts | |

| ≤ 5 cm | 3 (25%) |

| > 5 cm | 9 (75%) |

| Hepatic tumor size, cm | |

| Median | 6.4 |

| Range | (3.1-9) |

| Distribution of liver metastases, pts | |

| Unilobular | 4 (33%) |

| Bilobar | 8 (67%) |

| Number of liver metastases, pts | |

| 1 | 2 |

| 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 1 |

| > 3 | 7 |

| Solitary | 2 (17%) |

| Multiple | 10 (83%) |

| Number of extrahepatic | |

| recurrent lesions, pts | |

| 1 | 3 (37.5%) |

| > 1 | 5 (62.5%) |

Four patients presented with synchronous liver metastases. One of them was operated as emergency case for acute bleeding from a GIST in stomach; thereby the liver metastases were identified. In this case the metastases were resected after neoadjuvant treatment with TKI (imatinib mesylate, 400 mg). The metastases recurred and the therapy was switched to sunitinib matate. The other three patients were treated by neoadjuvant TKI-therapy and no one was operated neither for the primary tumor nor for the metastatic disease and there was not any progression of the disease. During the last follow up these patients presented a stabile disease under TKI-therapy (sunitinib matate or sorafenib) except for one case with progressive disease.

Treatment of patients with metachronous liver metastasesWithin a median time interval of 41 months, eight patients presented metachronous metastases. In all of these cases, the primary tumor was already R0-resected either without (n = 4) or after (n = 4) neoadjuvant TKI-therapy. Neoadjuvant TKI-therapy because of hepatic disease was given to all these patients for a median duration of seven months (range, 5-8 months) because of the borderline resectable or unresectable primary disease.

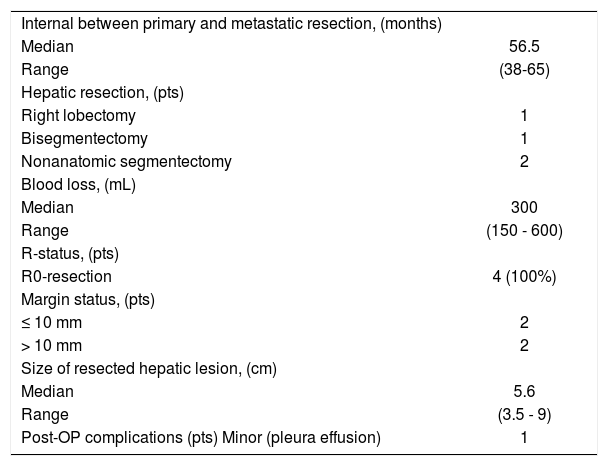

After TKI-therapy, the liver metastases were estimated as resectable in three patients. The data regarding the surgical treatment of liver metastases are listed in table 2. Postoperatively all patients received imatinib mesylate (400 mg pro day) therapy which was converted to other types (nilotinib or sorafenib) due to local recurrence in two cases within a period of nine months; all of them finally demonstrated a complete response.

Surgical treatment of hepatic metastases from GIST (n = 4).

| Internal between primary and metastatic resection, (months) | |

| Median | 56.5 |

| Range | (38-65) |

| Hepatic resection, (pts) | |

| Right lobectomy | 1 |

| Bisegmentectomy | 1 |

| Nonanatomic segmentectomy | 2 |

| Blood loss, (mL) | |

| Median | 300 |

| Range | (150 - 600) |

| R-status, (pts) | |

| R0-resection | 4 (100%) |

| Margin status, (pts) | |

| ≤ 10 mm | 2 |

| > 10 mm | 2 |

| Size of resected hepatic lesion, (cm) | |

| Median | 5.6 |

| Range | (3.5 - 9) |

| Post-OP complications (pts) Minor (pleura effusion) | 1 |

The other five patients which did not undergo surgery for metastatic disease were treated with imatinib mesylate (400 mg). In three cases we observed a complete or partial response and in the other two cases we switched to sunitinib matate and stable disease was temporarily achieved.

Adverse effects of imatinib mesylate were generally rare, mild and were well tolerated (nausea, vomiting, vertigo) No grand medical treatment was needed. Only a patient discontinued the imatinib mesylate treatment because of its toxicity (prerenal acute renal failure) and in another one the dosis was reduced. Effects of sunitinib malate therapy included hand foot syndrome which was mild and treated with cream containing urea 40% or tazarotene.

Interventional therapyTwo patients who received a surgical resection of liver metastases were treated with RFA (Figure 2) because of tumor recurrence after liver resection. The size of ablated liver lesion in the first patient was 2.5 cm (segment 4a). The second patient received twice RFA in a time interval of 30 months. The size of the two ablated lesions was 4 and 1.3 cm accordingly (segment 4a and 5). In both patients, a complete response at the RFA site was achieved and no complication was emerged. Of the patients who did not undergo surgical resection, noone received hepatic artery embolisation.

Extrahepatic diseaseIn four patients (33%) the metastases were confined only to the liver, in the other eight patients (67%) the liver metastases were accompanied by extrahepatic metastases; in all of them the extrahepatic metastatic disease was peritoneal metastases accompanied with either lung or lymph node or abdominal wall or adrenal grand or acetabulum metastases. Specifically, in 4 of the eight patients with peritoneal metastases an operation was performed either as ongological R0-resection or as emergency operation because of ileus or perforation. One patient had pulmonal metastasis and metastasis of adrenal grand as well and underwent a simultaneous metastasectomy with negative surgical margins. Lymph node metastases were also resected with negative surgical margins either intraabdominal in the framework of D2-lympadenectomy of GIST of stomach or extraabdominal as an axillary node dissection.

Follow-upThe median follow-up of 12 patients was 84 months (range, 30-152 months). No patient was lost during observation. Till the last follow-up, nine patients (75%) were alive; four of them remained free of disease, one with partial response, two with stable disease and two with disease’s progression. Death for progressive disease occurred in two cases (17%) and death for unrelated causes in one case. The overall 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year survival rates were 100, 100, and 91.6%, respectively.

The median follow-up period in the patients who received liver resection was 52 months (range 38-888). Three (75%) of these patients are alive with a mean survival time of 60 months (range 38-88). The 2-year und 3-year survival rates were 100% and 75%, respectively. Two patients (50%) developed recurrence within the remnant liver 3 and 14 months, after the hepatic resection. The recurrence was treated with RFA in the first patient or with further hepatic resections (bisegmentectomy, nonanatomic segmentectomy) and RFA in the second one.

DiscussionThe management of hepatic metastases from GIST remains a challenging clinical problem. Liver resection is the preferred and valuable treatment for liver metastases from GIST when complete resection can be achieved.10,11,28–30 Nowadays, major and extended hepatic resections can be safely performed since, as a result of advances in surgical and perioperative care, the risks of major hepatic resections have decreased remarkably.30 Therefore, surgical resection may provide a potential cure to an increasing proportion of these patients. In the series by DeMatteo et al 31 the 1-year and 3-year survival rates for patients who underwent hepatic resection of all visible disease were 90% and 58%, respectively. However, a large tumor burden in the hepatic parenchyma may prohibit resection given the risk of insufficient remaining liver tissue and subsequent postoperative liver failure. Furthermore, a partial hepatectomy could be of unclear benefit in case of multifocal liver disease involving both liver lobes. Generally, many patients with liver metastases from GIST are either unresectable due to diffuse intrahepatic disease or inoperable due to extrahepatic disease.11,32

The introduction of TKI is revolutionary in the treatment of metastatic GIST, representing a real major paradigm shift in cancer therapy, since it targets the specific molecular abnormalities, crucial in the etiology of tumor.33–35 Patients with primary unresectable liver deposits are clearly candidates for TKI treatment and may benefit from a neoadjuvant setting.36,37 However, neither the intervals between the start of treatment with IM and operation, nor the significance of surgical resection for the patients with metastatic GIST who have been treated with IM, has been completely elucidated.38–40 These questions may formulate the basis for future prospective studies of imatinib with complete resection of liver metastases of GIST. Generally surgical resection is recommended among responders either within six months of initiating TKI therapy to minimize the risk of acquiring secondary mutations responsible for TKI resistance38 or when patients demonstrate early signs of TKI resistance, such as “stagnation of tumor shrinkage” on radiographic imaging.41,42 In a workup of GIST for assessment of therapeutic response and detection of disease relapse, positron emission tomography using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG-PET) has been successfully involved, since a marked change in the glycolytic metabolism can be seen one month after therapy, and as early as 24 h after treatment initiation (Figure 3),43–45 in contrast to CT measuring conventional objective response criteria.46

In case of disease relapse under IM-therapy, the major problem is the tumor’s resistance caused by development of secondary mutations in exons 13 through 17 of the KIT gene or, less frequently, the PDGFR-a gene.47,48 An increase of the imatinib mesylate dose to 600 mg per day or a maximal dose of 800 mg per day is useful but its effectiveness only lasts for a short time. A change to another targeting agent, such as sunitinib, nilotinib or sorafenib, could improve the outcome and stabilize the disease,49,50 as shown in our cohort. But TKI-treat-ment for patients with recurrent or metastatic GIST seems be critical for achieving long-term survival.48 Therefore, measures to prevent acquired resistance are vitally important, since the combination of TKI-therapy with surgery really seems to prolong survival.29,42 Indeed, in the current study, patients with LM from GIST who underwent liver resection and TKI in a neo- and an adjuvant setting had a long disease-free and overall survival. But, on the other side, if a surgical resection is not feasible, a stabilisation of the disease can be though achieved, as it is shown in our study, even if a disease relapse or TKI resistance appears, because of the multiple TKI choice. Other authors have already proposed that surgery in combination with adjuvant TKI-therapy results in improved survival10,42 but to our knowledge, it is the first study concerning GIST patients with liver metastases which shows that TKI-therapy in neoadjuvant setting may improve the survival. Depending on individual circumstances, we should choose the most desirable treatment modality, and the combination of surgical and TKI therapy should help to improve the prognosis of GIST patients in most cases.

Sometimes, liver resections may be inappropriate in patients not only because of bilobal metastases but also because of liver dysfunction, or severe co morbidities. In these cases interventional therapy (RFA) can be feasible, tolerable and effective local treatment as shown in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma and liver metastases secondary to colorectal cancer or other malignancies.15,16,51,52 Generally, it is proposed that patients with GIST who have stable systemic disease under TKI-therapy but have progression at one metastatic site seem to be particularly suitable for RFA. Consequently, RFA can delay a change in systemic therapy by achieving local control at the site of solitary disease progression in such patients. Furthermore, by combining RFA with resection, more patients may become candidates for surgical treatment, as the surgeon can resect larger tumors while ablating residual smaller lesions.52 RFA was well tolerated in our series of patients treated by experienced interventional radiologists. This is why RFA can be a potentially curative option for patients exhibiting partial response to imatinib with focal residual disease.53,54

The current study is based on a small number of patients, like most reports that address the issue of hepatic GIST metastasis and is limited by the fact that neoadjuvant and adjuvant TKI therapy was variable. However, this study provides further evidence indicating that hepatic resection in combination with TKI therapy improves survival for patients with GIST liver metastases with acceptable morbidity and mortality. In light of current evidence reported both here and elsewhere, we recommend that all patients with hepatic GIST metastases be treated aggressively with both surgery and TKI therapy in neaodjuvant and adjuvant setting before clinical signs of TKI resistance become apparent.

ConclusionA well-planned multidisciplinary approach should be the mainstay of the management of hepatic metastatic GIST.55 Selection of appropriate patients for hepatic resection of metastatic GIST must be individualized and must include an extensive evaluation of the extent of the disease. But surgery can form only part of the therapy for hepatic metastatic GIST. Combining surgery with TKI treatment not only in adjuvant but also in neoadjuvant setting is the most effective management for these patients. But even TKI therapy alone could improve overall survival. In selected cases, interventional methods may also play an important role. Powerful multicenter studies are needed to establish general guidelines for the appropriate treatment of these patients.

Financial Support or Grant for this WorkNone.

Conflict of InterestNone to declare.