Infantile hepatic hemangioendothelioma (IHHE) is a benign liver tumor, associated with hypothyroidism and vascular malformations along the skin, brain, digestive tract and other organs. Here, we determined a single-center patient cohort by evaluating the effectiveness and safety of propranolol and sirolimus for the treatment of IHHE.

Patients and methodsWe performed a monocentric and observational study, based on clinical data obtained from 20 cases of IHHE treated with oral propranolol and sirolimus at the Shanghai Children's Medical Center (SCMC), between December 2017 and April 2019. All cases were confirmed by abdominal enhanced CT examination (18/20, 90%) and sustained decrease of alpha fetoprotein (AFP) (2/20, 10%).

Propranolol treatment was standardized as once a day at 1.0mg/kg for patients younger than 2 months, and twice a day at 1.0mg/kg (per dose) for patients older than 2 months. Sirolimus was used to treat refractory IHHE patients after 6 months of propranolol treatment, and initial dosing was at 0.8mg/m2 body surface per dose, administered every 12h. Upon treatment, abdominal ultrasound scanning was regularly performed to evaluate any therapeutic effects. All children were followed up for 6–22 months (mean value of 12.75 months). The clinical manifestations and therapeutic effects, including complications during drug management, were reviewed after periodic follow-up.

ResultsThe effective rate of propranolol for the treatment of children with IHHE was 85% (17/20). In most cases, the AFP levels gradually decreased into the normal range. A complete response (CR) was achieved in 3 cases, partial response (PR) for 14 cases, progressive disease (PD) for 2 cases and stable disease (SD) was only detected once. Lesions decreased in two PD patients after administration of oral sirolimus. No serious adverse reactions were observed.

ConclusionThis study indicates that both propranolol and sirolimus were effective drugs for the treatment of children with IHHE at SCMC.

Infantile hepatic hemangioendothelioma (IHHE) is a common benign liver tumor, with an incidence of approximately 1 in 20,000 live births. IHHE can be categorized into focal, multifocal and diffuse, and it is frequently associated with hypothyroidism and vascular malformations of skin, brain, digestive tract and other tissues/organs [1–3]. The clinical manifestations of IHHE typically start before 6 months of age. Major complications that may lead to higher mortality rates, such as congestive heart failure (CHF), Kasabach–Merrit phenomenon (KMP) and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), may be present due to increased intrahepatic vascular shunt [4,5]. The pathogenesis of IHHE appears to involve the multiplication of vascular endothelial cells during embryonic development but still, it has not been fully characterized. Typically, IHHE is diagnosed by Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), abdominal ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT) and contrast-enhanced arterial phase CT [5].

To date, some cases of IHHE with small focal lesions do not require therapy, since spontaneous regression frequently occurs over several months. In contrast, more aggressive therapies may be required for multifocal or diffuse IHHE, especially in cases involving other organ dysfunction. These potential therapies include orthotopic liver transplantation or hepatic artery ligation, often combined with the use of digitalis, diuretics, and steroids. Meanwhile, some studies have suggested that propranolol can be effective for IHHE treatment, and its side effects are manageable after symptomatic treatment. Indeed, propanolol has now been recommended as a first-line treatment for children with IHHE [6,7]. Due to the drug etiology, it may also regulate the proliferation of vascular endothelial cells via cathecholamines and/or modulate VEGF pathway [8]. Sirolimus is a serine/threonine kinase which, in turn, plays a pivotal role in cell mortality, angiogenesis and cell growth [9,10]. As such, it has been used to treat kaposiform hemangioendothelioma (KHE). In the present study, we examined 20 cases of IHHE patients treated with oral propranolol and sirolimus at SCMC.

2Methods2.1Patient cohortTwenty children with IHHE who were treated with oral propranolol at the SCMC, between December 2017 and March 2019, were included in this study. Written informed consent, supported by the Ethics Committee of SCMC (SCMCIRB-K2019043), was received by all participants. Standard IHHE diagnosis was based on abdominal enhanced CT and sustained decreased AFP. A series of tests including blood routine, liver and kidney function, electrocardiogram, echocardiography, and DIC were assessed before treatment. Two patients switched to sirolimus due to the poor efficacy of propranolol.

2.2Treatment with propranolol and sirolimusTreatment with oral propranolol (Sinopharm Shantou Jinshi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, 10mg/piece) was performed once or twice a day, at a dose of 1.0mg/kg, in patients younger or older than 2 months, respectively. Sirolimus (Hangzhou Sino-American East China Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, 1mg/ml) was used to treat refractory IHHE patients after 6 months of propranolol treatment, and initial dosing was at 0.8mg/m2 body surface per dose, administered every 12h.

2.3Follow-up and evaluationUltrasound examination was performed to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy on a monthly basis. Clinical manifestations, treatment schedule, complications and prognosis follow-up were reviewed and analyzed. Specific indicators of therapeutic efficacy included reduction in lesion size, AFP level, heart rate, blood pressure and blood sugar levels.

The responsiveness to therapy was categorized as the following [11]: (i) Complete Response (CR), defined as a complete disappearance of either the lesion (clinical and/or radiological) and/or the symptoms, (ii) Partial Response (PR), defined as a reduction of >20% in size of the lesion (clinical and/or radiological) and improvement in symptoms, (iii) Progressive Disease (PD), defined as an enlargement of >20% in size of the lesion (clinical and/or radiological) or as new lesions appearing, and (iv) Stable Disease (SD) as none of above. Effective and ineffective groups were related to CR/PR and PD/SD categories, respectively.

2.4Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed using Graph Pad Prism software (Version 6). Chi-square and t-tests were used to evaluate the efficacy of prolonged propranolol treatment of IHHE. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3Results3.1Clinical characteristics of the patientsIn this study, 20 IHHE patients were evaluated and then treated with oral propranolol and/or sirolimus between December 2017 and March 2019. From the total amount of participants, 9 were male and 11 were female, and their age at diagnosis ranged from fetal to 48 months. The mean age at the treatment was 5.55 months, and the median was 2.0 months. All children were followed up for 6–22 months, with a mean value of 12.75 months. Multiple lesions were observed in 3 patients, while the rest presented single lesions (Table 1). Patients were examined by ultrasound scanning every month to confirm lesion reduction.

Characteristics for the 20 children with IHHE.

| Demographic | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender-no. (%) | ||

| Male | 9 | 45 |

| Female | 11 | 55 |

| Age at diagnosis, months | ||

| Median age | 2 | |

| Range | 0–48 | |

| Age group-no. (%) | ||

| 0–6 months | 16 | 80 |

| 6–36 months | 3 | 15 |

| >36 months | 1 | 5 |

| Diagnosis mode-no. (%) | ||

| Ehanced MRI | 18 | 90 |

| Decreased AFP level | 2 | 10 |

| Lesion, no. (%) | ||

| Multiple | 3 | 15 |

| Single | 17 | 85 |

| IHHE maximum diameter (cm) | ||

| Median diameter | 5.36 | |

| Mean diameter | 5.3 | |

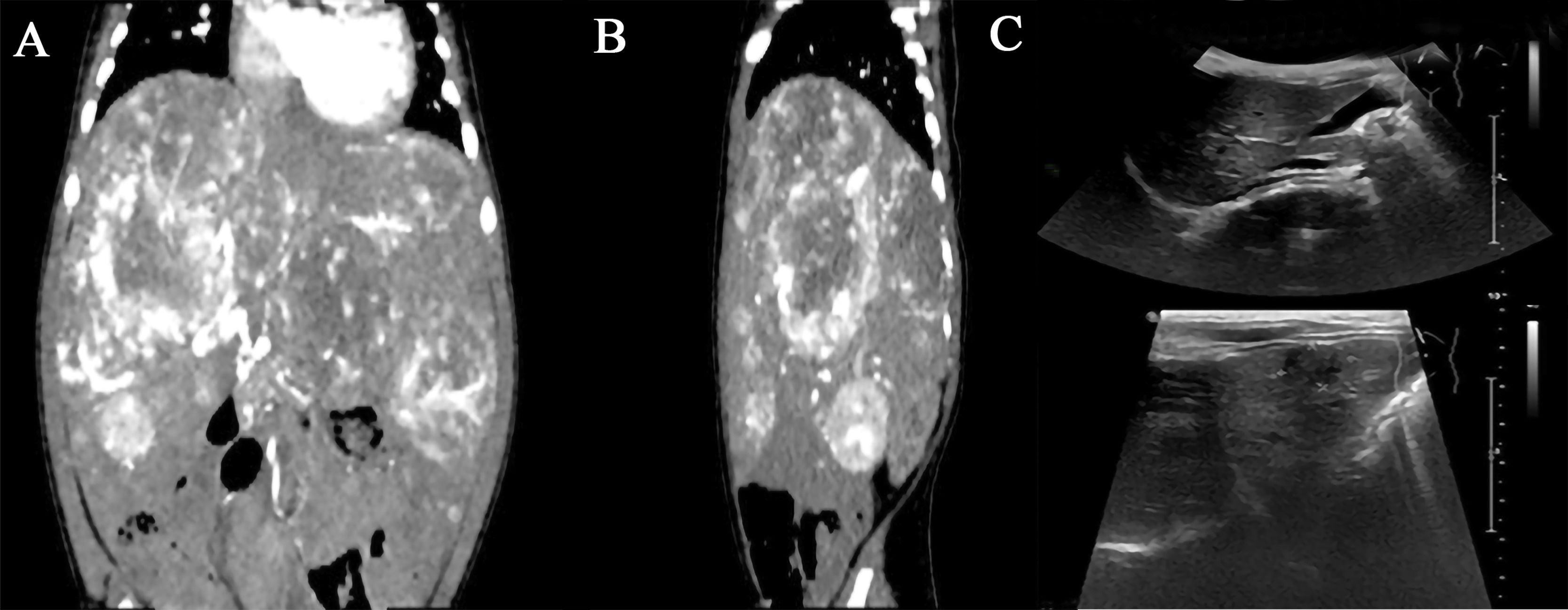

We conducted a long-term follow-up of 20 patients with IHHE, who had been treated with propranolol, and further assessed the drug efficacy in terms of changes to the lesion size. Blood, liver and kidney functions as well as DIC were re-examined monthly during medical follow-up. Likewise, ultrasonic examination was performed every month. The longest period of treatment with the medication was 22 months, while the shortest period was 4 months. Overall, 85% (17/20) of children obtained a satisfactory response to the treatment with oral propranolol, and therapy ended when patients had a good or excellent response. In fact, CR was observed in 3 cases, PR in 14 cases, PD in 2 cases and SD was only detected in one case (Table 2). A remarkable reduction in lesion size was found in three patients after oral propranolol treatment. In this case, one patient was treated for about two months (Fig. 1), one for 5 months and another for ten months (Fig. 2). Sirolimus was successfully administered for about three months in patients where propranolol treatment was ineffective and then discontinued. For instance, one SD patient was treated with propanolol for 20 months with good efficacy, but treatment was later ineffective or dosing was slightly increased due to refractory effects. Although this patient was treated with hormonal therapy, no significant improvement was observed. So, upon alternate treatment with sirolimus, lesion was diminished but the patient's family discontinued the use of sirolimus due to severe oral mucositis. To investigate the therapeutic effects of propranolol, patients were divided into three subgroups according to the time of administration with oral propranolol (Table 3). No serious adverse reactions were found after propranolol treatment. Grade 3 mucositis was also found after sirolimus treatment.

Oral propanolol in IHHE.

| Average medication time, months | 12.75 | |

| Median of medication time, months | 10.5 | |

| Treatment for 0–6 months, no. (%) | 3 | |

| Effective | 2 | 66.7 |

| Ineffective | 1 | 33.3 |

| Treatment for 7–12 months, no. (%) | 11 | |

| Effective | 10 | 90.9 |

| Ineffective | 1 | 0.1 |

| Treatment for 13–24 months, no. (%) | 6 | |

| Effective | 5 | 83.3 |

| Ineffective | 1 | 16.7 |

Since clinical data, related to the use of propranolol and sirolimus in IHHE, is still very limited, here we successfully evaluated 20 cases of IHHE patients treated with oral propanolol combined with (or not) sirolimus. Our study aimed to assess the efficacy of propanolol and sirolimus in the treatment of IHHE. The overall response of propanolol was 85% (17/20). Likewise, no serious side effects due to propranolol treatment in the enrolled IHHE patients were identified. Sirolimus was eventually used for patients who were refractory after oral propranolol treatment. Two PD patients were still in remission after sirolimus treatment.

Since 2008, propranolol has been used for the treatment of hemangiomas [12], and some studies have even supported the use of propranolol for the treatment of IHHE [6,13–15,19,20]. Maalouland colleagues [13] reported that a 5-month-old girl with IHHE was treated with low-dose propranolol, initially at 0.5mg/kg/day and gradually increasing to 1.5mg/kg/day. The dose was maintained for 12 months and then gradually decreased. After 12-month follow-up, IHHE lesions was completely subsided. Fortunately, the safety level of propranolol treatment is very high and, basically, no side effects were detected in Patients’ growth and development. In fact, Avagyan and colleagues [6] have recommended propranolol as a first-line drug for the clinical treatment of diffuse IHHE. Again, Varrasso and colleagues have reiterated that propranolol is still a first-line treatment for life-threatening IHHE [19].

Approximately 80% (16/20) of these lesions are initially identified within 6 months, which is consistent with previous studies [6,13]. Specifically, the average diagnosis time in our study was 2 months, in contrast to other studies performed for one [1] and three [7] months. Compared with these other studies, no serious complications, such as CHF, KMP, DIC, were observed before administration of oral propranolol. Additional studies have pointed out an average reduction of ∼50% in lesion diameter, after one month of propranolol treatment [17]. However, in our current study, most of the cases required treatment for 6–8 months before the lesion volume could shrink by ∼50%.

Sirolimus is a serine/threonine kinase which, in turn, plays a pivotal role in angiogenesis cell growth and viability [15]. Therefore, the efficacy of sirolimus in IHHE is possibly due to its anti-proliferative properties. As a benign liver tumor, IHHE is often associated with malformations of the digestive tract. Since this association is of particular concern, more attention is warranted to the individualized treatment of severe IHHE. Similarly, individualized treatment may be required when IHHE is linked to arteriovenous shunt and other related complications. Other reports have indicated that IHHE lead to additional complications such as KMP and CHF [15,16], but no severe clinical manifestations were identified in our 20 cases. Since no major complications have been reported, propranolol was routinely used for children with lesions over 4cm. Besides the three cases of multiple IHHE identified in our study, all remaining patients acquired single lesions. In this work, patients were treated with propranolol immediately after diagnosis and/or clinical appearance. Surgery and interventional therapy were not applied to the 20 enrolled patients. After diagnosis, we were required to distinguish IHHE from hepatoblastoma. After treatment with propranolol, the AFP level of most patients decreased significantly. Since propranolol treatment presents a good efficacy and very limited side effects, it may be recommended as a first line of treatment. On the other hand, sirolimus may be used as an adjuvant, but this alternate drug should be administered with more caution.

Here we introduced, for the first time, the use of sirolimus in patients with refractory IHHE in China. After treatment with propranolol for 20 months, patient was treated with sirolimus and, therefore, lesions were dramatically reduced but rebounded after stopping the drug treatment. A selection bias might be involved in our study, since some patients had relatively mild symptoms. Due to the small number of cases analyzed and the mild symptoms that were identified, the effectiveness of sirolimus is not yet validated.

Based on our results and other published reports [13,17,18], oral propranolol appears to be effective for decreasing lesions in IHHE patients. Sirolimus may be a potentially effective option for IHHE patients who were refractory to propranolol.AbbreviationsIHHE infantile hepatic hemangioendothelioma congestive heart failure Kasabach–Merrit phenomenon disseminated intravascular coagulation magnetic resonance imaging computed tomography

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participateThis study was given approval by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Children's Medical Center (SCMCIRB-K2019043), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.

We thank Dr. Song Gu for sharing his expertise in treating patients with IHHE as well as for his selfless help.