The hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype is an important predictive outcome parameter for pegylated interferon plus ribavirin therapy. Most published therapeutic trials to date have enrolled mainly patients with HCV genotypes 1, 2 and 3. Limited studies have focused on genotype 4 patients, who have had a poor representation in pivotal trials. Our aim was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of treatment with standard dose pegylated interferon alfa-2a in combination with weight-based ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C genotype 4. In this prospective observational study, 198 patients with HCV-4 were included in this study from February 2004 to August 2005,188 patients who received at least 1 dose of drugs were included in the ITT analysis and they were treated with pegylated interferon alfa-2a and ribavirin for 48 weeks. Baseline and demographic characteristics, response to treatment at weeks 12, 48 and 72, and the nature and frequency of adverse effects were analyzed. Virological response at week 12 was achieved in 144 patients (76.6%). Virological response at the end of treatment was present in 110 patients (58.5%). At week 72, 99 patients presented SVR (52.7%). The reported adverse events were similar to those found in the literature for treatments of similar dose and duration. In conclusion, combined treatment with pegylated interferon alfa-2a and ribavirin was well tolerated and effective in chronic hepatitis C genotype 4, yielding response rates between those reported for genotype 1 and those of genotypes 2-3.

According to WHO estimates, 130-170 million people are chronically infected worldwide with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) and 3-4 million people are infected with HCV each year.1,2 HCV is a RNA virus characterized by genetic heterogeneity. It has been classified into 6 different genotypes, with several subtypes, according to the percentages of homologous sequences.3 These genotypes have different prevalence and geographical distribution. While strains, 2 and 3 are common in Europe and the United States, genotypes 4, 5 and 6 are more frequently found in Middle East and the African continent.1,4 Although genotype differences do not seem to influence the course of the disease,5 the HCV strain is one of the many factors that influence the outcome of antiviral therapy,6–8 It has been estimated that approximately 34 million people are chronically infected by genotype 4 worldwide. This genotype represents more than 80% of hepatitis cases in the Middle East and Africa. Egypt has the highest HCV prevalence (22% in 2011),2 with HCV-4 responsible in 90% of cases.9 Although the proportion of HCV-4 in African countries has currently stabilized, the frequency of HCV-4 infections in Europe, and particularly in Mediterranean countries, is increasing. HCV-4 prevalence is 10-24% in some areas of France, Italy, Greece and Spain.10–13 This increase has been related to immigration and also the movement of parenteral drug abusers across frontiers.9,13,14 Hepatitis patients with HCV-4 have been generally underrepresented in clinical trials for the registration of drugs usually used to treat hepatitis C, although these patients account for 20% of all chronic hepatitis C infection cases in the world.14,15 The availability of data on G4 patients is limited, although some information can also be extracted from studies performed with HIV and HCV-4 co-infected patients.16

Patients infected with HCV genotypes 1 and 4 have more difficulties in responding to interferon treatment, and percentages of response to combined interferon and ribavirin therapy are lower in these patients than response rates of those infected with genotypes 3 and 4. In the last few years, continuous improvements in therapies for chronic hepatitis C have considerably improved treatment efficacy.17 The combination of ribavirin (RBV) with pegylated interferon (peginterferon) constituted significant progress, increasing significantly response rates for all genotypes,18,19 including these difficult-to-treat genotypes 3 and 4.20 The use of peginterferon-α2a combined with RBV has shown SVR rates to be two-fold higher than with interferon monotherapy,21,22 and the combination of peginterferon and RBV produced SVR in 45% of a genotype 4 subgroup compared to 0% achieved with a combination of interferon and RBV.23 Two studies in Europe and Middle East have reported SVR results between 43 and 70%.24,25 Although this effect is clearly higher than SVR percentages achieved by genotype-1 patients (42-46%), HCV-4 response is still far from the 76-82% SVR rate reported for chronic hepatitis C genotypes 2 and 3.26 An unexpected finding in trials performed in Egypt was that HCV-4 patients achieved higher SVR rates than European and African patients, under the same therapeutic conditions.27

Our goal was to verify that the findings of previous studies are reproduced in routine clinical practice with a representative population of Spanish patients infected with genotype 4 who had not been previously treated. We analyzed both efficacy and safety of combination therapy with pegylated interferon alfa-2a and ribavirin in these patients.

Material and MethodsExperimental procedures- •

Study design and patients. We performed multicenter, prospective and observational study to assess the safety and efficacy of combined therapy with pegylated interferon alfa-2a (Pegasys®, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and ribavirin (Cope-gus®, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) in patients with previously untreated chronic hepatitis C genotype 4. This observational study included patients from 31 participating centers, with the original intention of reaching 150 G4 participants. As no comparison was intended, no sample size calculation was performed. Patient enrollment started in February 2004 and the study ended in August 2005. Only patients between 18 and 65 years of age, with a histological hepatitis diagnosis, HCV seropositive status, detectable HCV-RNA levels in serum (genotype 4) and aspartate transaminase levels higher than 1.5 times normal values during at least 6 months were included. Exclusion criteria were any other hepatic disorder, decompensated cirrhosis, viral co-infections, immunodeficiency, drug abuse in the past 6 months before treatment onset, active alcoholism and severe comorbidities (respiratory or renal insufficiencies, epilepsy, depression, insomnia). Pregnant or lactating women and patients with abnormal laboratory findings suggesting anemia, altered coagulation or autoimmunity were excluded. Informed, written consent was obtained from all participants, and studies were performed according to the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. All procedures were approved by the ethics committee of the coordinating center.

- •

Treatment and assessment of efficacy. All participating patients received combined therapy with peginterferon-α2a (180 μg/week) and weight-adjusted RBV (1,000-1,200 mg/day) for 48 weeks. This regimen was decided according to the revision made by Diago, et al.,28 this being the optimum dose for genotype 4 patients. The main outcome of interest was response to treatment, defined as undetectable HCV-RNA in serum 24 weeks after treatment completion (sustained virological response, SVR) and serum ALT reduction below the upper limit of normal range. Secondary variables were undetectable serum HCV-RNA 12 weeks (early virological response, EVR), 24 weeks, and 48 weeks (end of treatment viral response, ETVR) after treatment onset. HCV-RNA levels were measured in each center with AMPLICOR-HCV following their protocols. Treatment continued after 12 weeks only if a 2-log10 decrease of HCV-RNA was observed at this time point, which was otherwise suspended, and maintained until negative levels of viral RNA could be verified after 48 weeks of treatment. Baseline and demographic characteristics were recorded at the beginning, and efficacy and safety variables at all time points.

Routine laboratory tests were scheduled throughout the duration of the study, first at 2-week intervals in the first months, monthly until 12 weeks of treatment and then every 3 months until the end of treatment. The patients were monitored for adverse events and medication compliance. Adverse events were graded as mild, moderate, or severe according to WHO guidelines and treatment suspended or modified according to severity: both drug doses were reduced to 50% in case of moderate and severe adverse events and suspended if severe adverse events did not disappear. Dosage could be again increased to the original levels if adverse events disappeared.

Statistical analysesEfficacy analysis was based on intention-to-treat analysis (ITT) with IC 95%, and per-protocol analysis (PP) analysis was also applied. Patients who discontinued the study or were lost during the follow-up period were considered non-responders. Response to treatment at different time points in relation to different analytical and demographic characteristics were analyzed using Student t-test or Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney as appropriate and χ2 test performed for categorical variables. All statistical analyses were carried out using the SAS® software package (version 8.2). Descriptive values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or percentages. The severity of adverse was classified according to WHO guidelines and causal association following FDA guidelines to calculate rates within the safety population (SP).

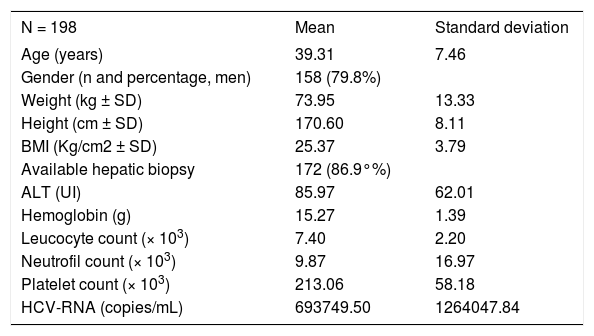

Results and DiscussionThe baseline characteristics of the final 198 Spanish patients included (ITT) are presented in table 1. A total of 63 participants did not finish the study (33.5%): 11 due to patient’s decision; 13 because of adverse events; 35 did not respond to treatment at week twelve. Baseline ALT was 95 IU/mL (SD = 62) and HCV-RNA quantified mean 693,749 copies/mL (SD = 1,264,047).

Baseline and demographic characteristics.

| N = 198 | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 39.31 | 7.46 |

| Gender (n and percentage, men) | 158 (79.8%) | |

| Weight (kg ± SD) | 73.95 | 13.33 |

| Height (cm ± SD) | 170.60 | 8.11 |

| BMI (Kg/cm2 ± SD) | 25.37 | 3.79 |

| Available hepatic biopsy | 172 (86.9°%) | |

| ALT (UI) | 85.97 | 62.01 |

| Hemoglobin (g) | 15.27 | 1.39 |

| Leucocyte count (× 103) | 7.40 | 2.20 |

| Neutrofil count (× 103) | 9.87 | 16.97 |

| Platelet count (× 103) | 213.06 | 58.18 |

| HCV-RNA (copies/mL) | 693749.50 | 1264047.84 |

EVR at week 12, defined as undetectable HCV-RNA or a 2-log decrease from the baseline HCV-RNA levels, was achieved in 76.6% (n = 144). Nine patients discontinued before week 12. The 144 responding patients continued treatment and 110 (58.5%) achieved viral response at treatment completion (ETVR) and 27 abandoned between week 12 and week 48 of treatment. Seven of these patients presented only transitory response. SVR (72 weeks from treatment onset) was verified in 52.7% (n = 99), and 9 patients (4.8%) relapsed (Figure 1).

A total of 849 adverse events were observed in 183 patients (92.4%), and 177 (89.4%) were considered to be treatment-related. The most prevalent adverse events were general disorders such as asthenia (n = 94; 42.93%) and irritability (n = 35; 17.17%), as well as polymyalgia (n = 13; 6.57%) and cephalea (n = 29; 13.13%). Psychiatric disorders included anxiety (n = 16; 8.08%), depression (n = 20; 8.59%) and insomnia (n = 52; 25.25%). A total of 20 (10.1%) were classified as severe, 19 (9.6%) were treatment-related. The most prevalent severe adverse events reported included neutropenia (n = 6; 2.53%), anemia, thrombocytopenia, and weight loss (n = 2; 1.01% each).

Our study results, with an SVR rate of 53% in Spain, confirmed the hypothesis that patients with genotype 4, traditionally considered “difficult to treat”,15 can achieve response rates higher than those of genotype 1 patients under the same conditions. These findings are similar to those described in previous studies. The small genotype-4 patient population of Fried and Hadziyannis29,30 receiving doses of 1,000-1,200 mg/day (by weight < 75 kg or > 75 kg) and treated for 48 weeks, achieved the highest SVR rates (79%), but efficacy results of a previous study is lower, with the SVR rates in genotype 4 patients at 43%.20 This study, performed in a usual clinical practice environment and with a much higher sample size of HCV-4 patients than the aforementioned trials, presents a lower SVR rate, but our SVR results are still higher than sustained response rates of genotype 1 patients.29 Greater sustained response rates are obtained in populations of the Middle East and Egypt, supporting previous observations on the differences in response to treatment caused by interindividual characteristics, ethnicity, viral subtypes and mode of transmission described by several authors.24,31,32 Although the concept of response-guided therapy has not been validated at present for patients with HCV-4, the kinetics of viral clearance as shown in previous studies suggest that patients with RVR may be candidates for short treatment at 24 weeks and patients with RVT at 36 weeks.15 Continuation of treatment to 72 weeks can be considered for patients with slow response.18,19 The percentage of patients who discontinued in our study was slightly higher than in randomized trials (20%),33 but dropout rates were similar or even lower than the usual occurrence in clinical practice.34 Our observations indicate that the combination of pegylated interferon alfa-2a and ribavirin was well tolerated and adverse effects appeared were often in accordance with those previously reported in the literature. Most of these were mild to moderate reported adverse events not unusual nor unexpected.35 This study has the limitation that HCV-RNA levels 4 weeks after treatment onset were not collected to assess rapid viral response (RVR), which is a predictive parameter of more recent appearance than the dates of our study.36,37 Our design was not randomized, so there is no control group, and at the time recent techniques to detect interleukin 28B, currently offering such good results,38,39 were not available.

A study including a larger number of patients with genotype 4 could be of use in the immediate future, assessing the impact of new treatments for hepatitis C in this genotype, such as protease inhibitors (tela-previr and boceprevir), polymerase and cyclophilin inhibitors (R7128, Debio 025), nitazoxanide, etc.40 In conclusion, our results show that, although the high SVR rates achieved in randomized trials could not be reproduced in routine clinical practice conditions, patients traditionally considered very difficult to cure could benefit from double therapy with pegylated interferon alfa-2a and ribavirin with more success than genotype-1 patients. This is the study with the highest number of monoinfected patients with genotype 4 in Spain, and our findings indicate that combination therapy with peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin is safe and effective for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C genotype 4, with rates response between genotype 1 and those of 2-3.

Grants and Financial SupportNone.

AcknowledgementWriting support was provided by Dr. Blanca Piedrafita of Medical Statistics Consulting S.L. and funded by Roche.

Abbreviations- •

HCV: hepatitis C virus.

- •

G: genotype.

- •

SVR: sustained virological response.

- •

RBV: ribavirin.