The literature has usually omitted family factors from the development of strategic models of family firms. These businesses have instead been analysed using traditional models and this has led to divergent results about their performance. This paper considers the overlap of family, business, and individuals in producing the concept of familiness – whose composition is approached from the perspective of social capital and open systems. This approach bridges the research gap regarding the composition of familiness (which has been traditionally measured as an indicator of the implication of the family in the business) and the component and essence approaches to family business are compared.

La literatura ha eliminado tradicionalmente los factores familiares de los modelos estratégicos de las empresas familiares que han sido analizadas siguiendo modelos tradicionales, lo que ha conducido a resultados divergentes sobre su desempeño. Por ello, este trabajo considera el solapamiento de los sistemas familia, empresa e individuos para llegar al concepto de familiness, a cuya composición se aproxima desde la perspectiva de Capital Social y Sistemas Abiertos. De esta forma, se cubre la laguna existente en la investigación sobre la composición de familiness, para cuya medición se recurre, tradicionalmente, al indicador de implicación de la familia en el negocio, entre otros, equiparando de este modo los enfoques de componentes y de esencia de la empresa familiar.

The concept of familiness refers to the essence of the family business (FB). It is a concept related only to research associated with these businesses (Pearson, Carr, & Shaw, 2008). Familiness in the literature is used interchangeably with the terms ‘family involvement’ (Farrington, Venter, & Van der Merwe, 2011) and ‘family effect’ (Brines, Shepherd, & Woods, 2013). However, both these terms are linked with variables that are considered when defining FB (in terms of ownership and control) and symbolise the influence of the family on the business. These variables may be easy to observe and measure, but it is necessary to introduce other behavioural variables that enable researchers to determine the essence of FB and familiness, and so increase our knowledge of this diverse group of businesses.

This work contributes to the current literature on familiness and FB in two ways. Firstly, it proposes a composition of familiness from the perspectives of social capital (SC) and open systems (OS), and includes components (capital) not previously referred to as shapers of familiness. Secondly, it defines variables within each component of familiness that can be measured in all family businesses while considering both perspectives.

In addition to the introduction, this paper reviews the current approaches to the concept of familiness in the literature, from which the theoretical composition model has been shaped in, and several theoretical propositions to be tested empirically.

Familiness: concept and perspectivesFamiliness is a concept that is attracting considerable research interest regarding various aspects of FB (Rutherford, Kuratko, & Holt, 2008) while its definition goes back to work by Habbershon and Williams (1999). These authors were the first to define familiness from a focus of Resources and Capabilities approach to explain the competitive advantage or disadvantage of family businesses. Habbershon and Williams (1999) considered family businesses as ‘the unique bundle of resources a particular firm has because of the systems interaction between the family, its individual members, and the business’, and show the importance of individuals for fully understanding the processes related to FB (Klein & Kellermanns, 2008). This definition provides a unified system perspective of the competitive advantage and development capabilities of FB, and focuses on showing how the results obtained by a sub-system (family, business, or individual) affects the actions and results of other overall system components (Pieper & Klein, 2007).

The unified systems perspective shows continuous, systemic, and synergistic interactions between the parts of an FB as a social system: namely, the family that controls the business and is representative of the history, traditions, and life cycle of the family; the business, symbolising the structures and strategies used to generate wealth; and the individuals, family members who embody the interests, skills, and life stage of the managers/owners participating in the FB (Habbershon, Williams, & McMillan, 2003). However, this approach considers only the managers/family owners of the FB within the system of individuals, and excludes other family members who may, for example, be involved in the daily activities of the business without being managers or owners – as well as those family members who have no direct link with management, ownership, or the day-to-day running, but whose attitudes and behaviour can directly influence the competitive advantage or disadvantage of an FB.

It seems evident that for the familiness present in a business to be transformed into capacities that produce a competitive advantage, family involvement is required as a strategic element (Habbershon & Williams, 1999). This leads to the redefinition of familiness as: ‘resources and capabilities associated with the interactions and involvement of the family’ (Chrisman, Chua, & Litz, 2003).

In the literature, there are definitions that use the term ‘familiness’ interchangeably with the term ‘family involvement’ (Farrington et al., 2011) and ‘family effect’ (Brines et al., 2013), equating the component and essence approaches as analysed by Chrisman, Chua, and Sharma (2005).

However, Habbershon et al. (2003) focus on the notion of familiness and redefine it as the ‘idiosyncratic bundle of resources and capabilities at the company level that results from the interaction of systems’ and which in the case of an FB represents all the specific and systemic family influences in the business. Therefore, we in this definition of familiness a relationship between familiness and performance derived from competitive advantage (Pieper & Klein, 2007), with the resource and capabilities focus being the theoretical basis of this variable. Thus, the combination of resources from the interaction of these systems affects the management of family businesses, which achieve a competitive advantage if they accumulate and effectively manage such combinations (Chrisman et al., 2003; Colli, García-Canal, & Guillén, 2013).

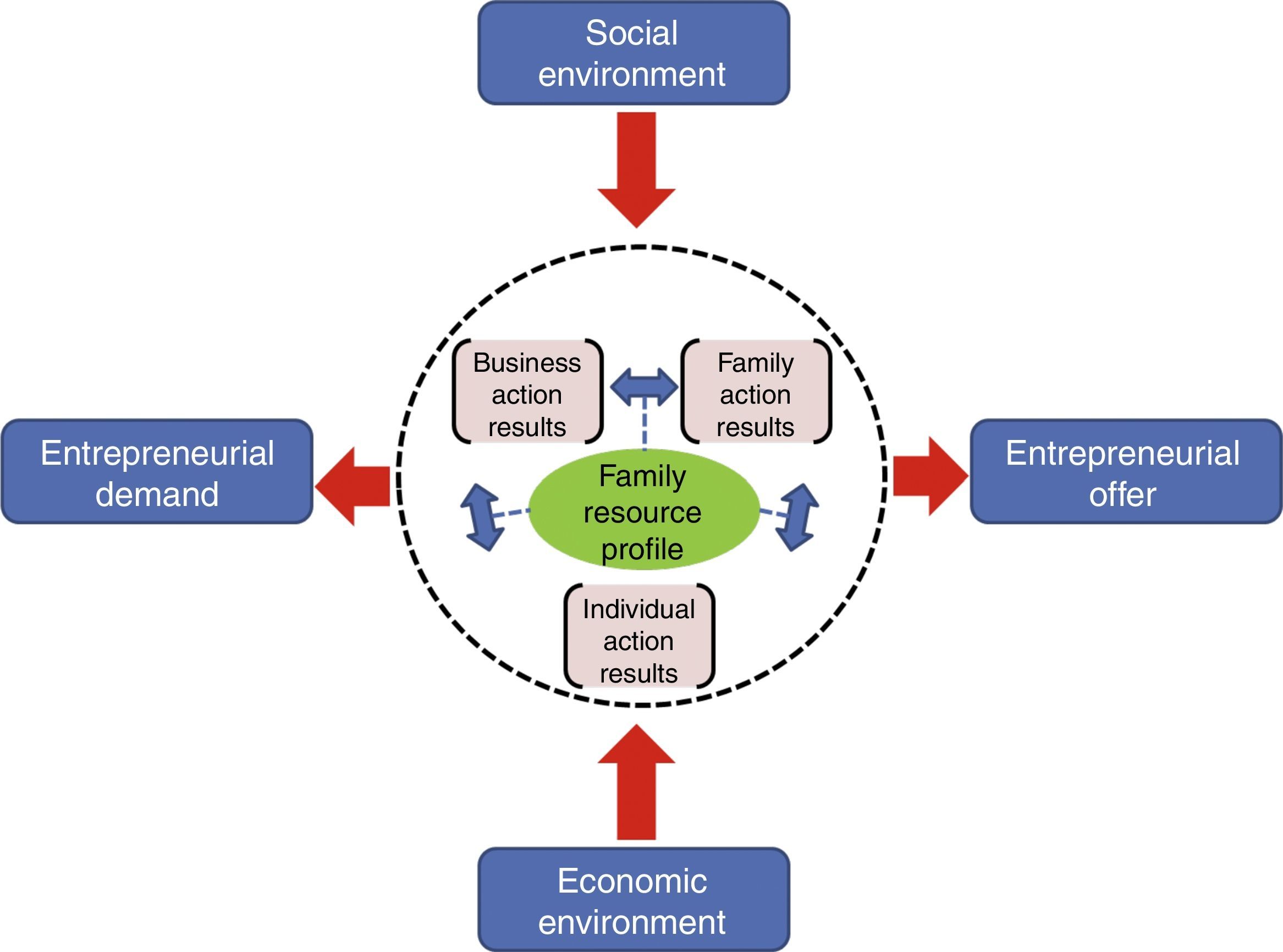

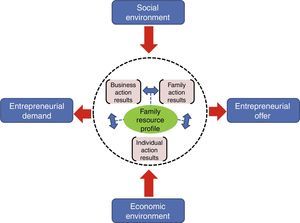

The analysis of this accumulation, management, and resource allocation is made through the family ecosystem approach as a perspective for the study of familiness (see Fig. 1). This perspective does not introduce variations to the concept of Habbershon and Williams (1999), but facilitates an understanding of the development processes and resource allocation from the reciprocal input–output interactions between the entrepreneur and the context (Habbershon, 2006). This approach warns that family and business cannot be separated without destroying the ecosystem in which they live. In this ecosystem, an important role is played by agents and the economic and social environment that promotes certain entrepreneurial and business activities, while limiting the development of others (Zacharakis, Shepherd, & Coombs, 2003).

This approach is based on concentric circles of contextual factors and input-output relationships. The outer ring shows the social and economic factors in the external environment that influence the FB. The middle circle shows the FB as the interaction between family, family members as individuals, and the business. As these parts of the subsystem interact within the ecosystem, they generate resources and distinctive capabilities that constitute the resource profile shown in the inner circle (representing an output of interactions in the system, as well as an input that returns to the business process).

Hence this model of ecosystem shows how the form of family organisation is a distinct context for entrepreneurship and causes practices and concepts of agency that impact on the business (Habbershon, 2006), especially when there is a clear ‘tangle’ between the role of family members and the business process. Thus, we refer to the resource profile (the familiness factor) as an explanation for the success or otherwise of an FB.

Finally, it highlights the open ecosystem approach created by Pieper and Klein (2007) and followed by Rautiainen, Pihkala, and Ikävalko (2012) who considered that we must analyse the interactions of each of the subsystems of the FB with the environment by applying a dynamic perspective and enabling the integration of multiple levels of analysis and various theories of FB. This perspective emphasizes that the FB system is in continuous contact with the environment through each of its subsystems (which have their own personalities and interact with each other).

Special importance is acquired by the stakeholders with who the individual (at a basic level of analysis) and the family and FB (at more advanced levels of analysis) creates, maintains, and/or destroys ties and connections that influence the configuration of social capital.

Moreover, this open system perspective considers various family models and cultural differences, and the effect on its evolution. This enables us to analyse and compare the endowment of familiness in family businesses in various cultural contexts and the evolution of its essence in the same cultural context.

Therefore, differing system perspectives change the focus of the analysis of FB from an indivisible whole to a set of subsystems in continuous interaction with the environment; and which incorporate inputs whose results affect and configure its social capital. Thus, this work focuses on the organisational social capital (Leana & Van Buren, 1999) associated with the employees of an organisation and which is considered as ‘a resource that reflects the character of social relations within a company’ (Su & Carney, 2013).

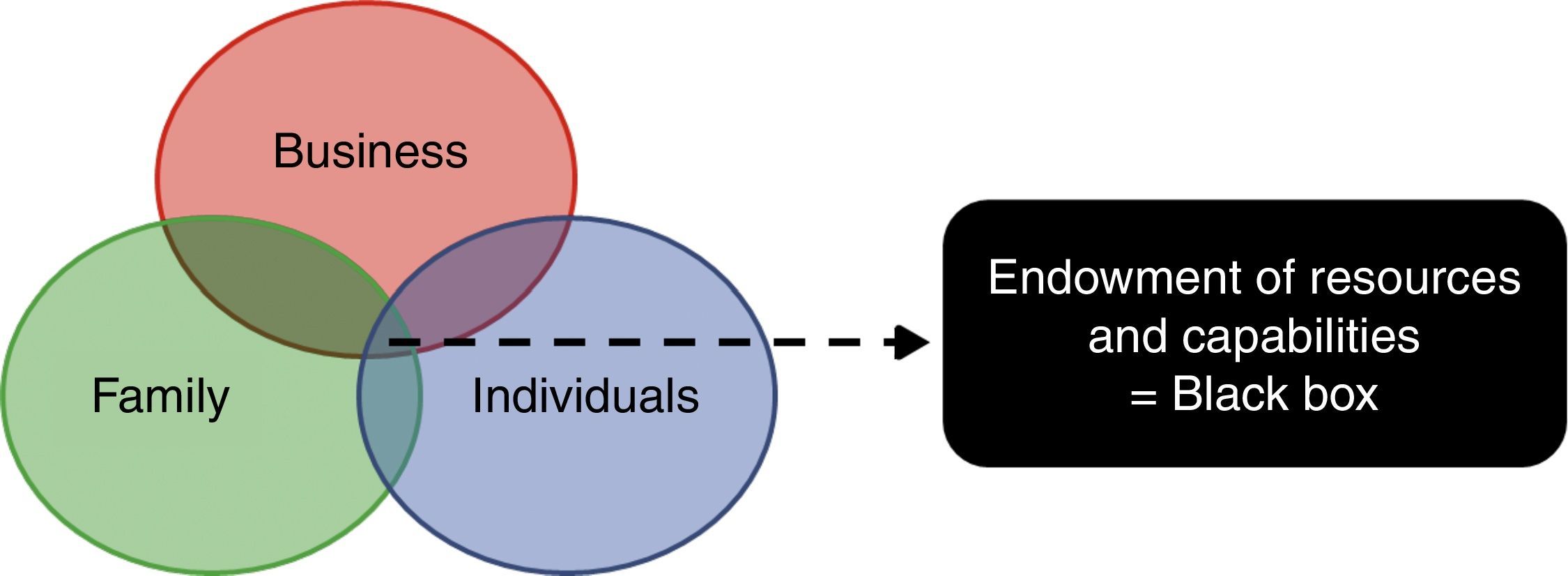

An examination of the various perspectives of familiness reveals that this is a difficult concept to empirically specify (López, Serrano, Gómez, & García, 2012). This difficulty has led to its consideration using proxy variables that are included in the definition of FB. However, there are no current studies determining exactly what forms familiness, nor what it contains. Thus, familiness is an unknown black box (Pearson et al., 2008), as shown in Fig. 2, that represents a gap in the research and on which this paper attempts to throw some light from the social capital perspective and considering the FB as the unit of analysis (seen as an open system in which each of its subsystems interacts with the environment and generate reciprocal effects with the other subsystems).

Familiness from the perspective of social capitalIn the literature, we can find various definitions of social capital (Arrègle, Hitt, Sirmon, & Very, 2007; Bourdieu, 1980; Gordon & Cheah, 2014; Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). They all refer to a set of possibly valuable current and potential resources that are associated with lasting relationships that can generate value – both at an individual and an organisational level. For Adler and Kwon (2002) social capital is within the internal structure of a group. This capital shows the nature of organisational social relations produced by the collective goals and shared trust of its members – and which translates into successful group actions that create value (Leana & Van Buren, 1999). In these definitions, a relation can be seen between the endowment of social capital in the business and the achievement of a competitive advantage through the creation of value.

The focus of this work on social capital is due to the consideration within the variable of familiness of dimensions associated with social and behavioural aspects of FB that have not been resolved in the various studies made in this field (specific to this type of business) and may configure its essence.

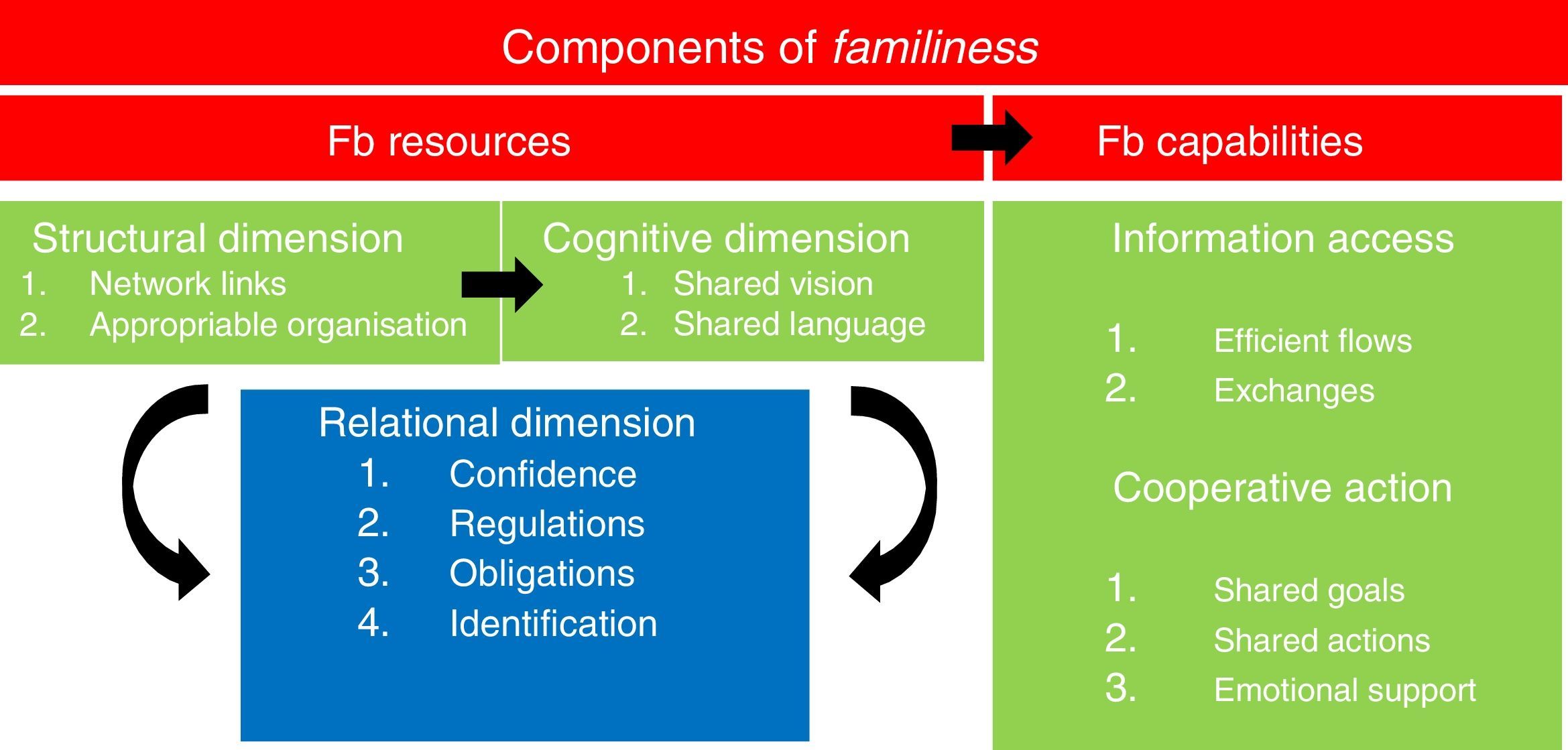

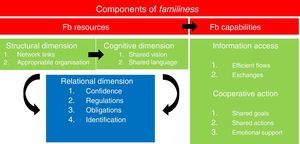

Arrègle et al. (2007) applied the social capital theory to depict mechanisms that described the effect of family social capital on the development of organisational social capital. Pearson et al. (2008) focused on identifying the components that make up familiness from the perspective of social capital, and considered that system focuses were inadequate to reveal the specific elements of that variable. The model of Pearson et al. (2008) focuses only on the interior of the FB and introduces elements difficult to define and measure (see Fig. 3).

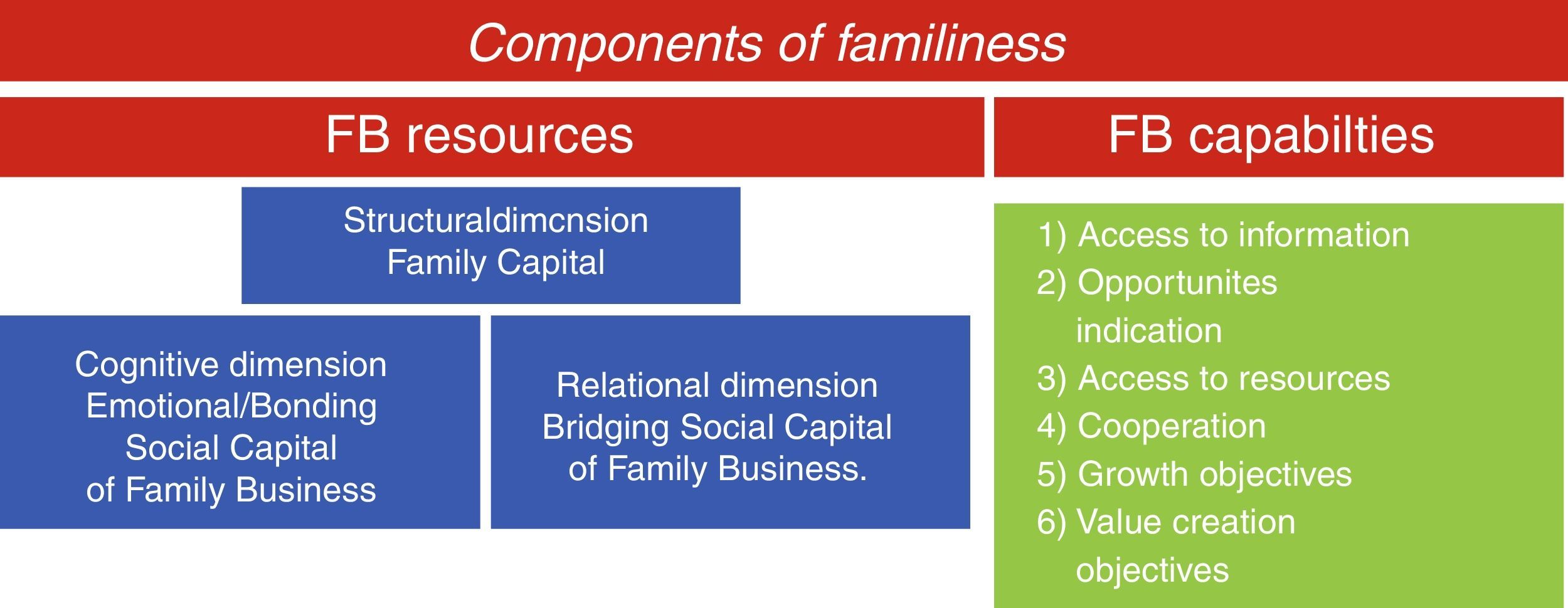

From this model, it can be concluded that FBs contain several resources of a structural, cognitive, and relational character that make up its capabilities in terms of access to information and cooperative actions. These resources can become a source of competitive advantage – or the opposite.

In the structural dimension, Pearson et al. (2008) consider that families have abundant internal links or connections that are appropriated by the FB. The cognitive dimension includes “resources that provide shared representations, interpretations, and systems of meaning among parties” (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998) and “include shared vision and purpose, as well as unique language, stories, and culture of a collective that are commonly known and understood, yet deeply embedded” (Tsai & Ghoshal, 1998), and these explain the importance of business continuity for the family (Pearson et al., 2008). Finally, the relational dimension considers the resources and capabilities derived from personal relationships (including confidence regulations, obligations, and identity) to be crucial for creating lasting bonds between individuals within a group (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). These relationships influence behaviour, and aspects such as cooperation, trust, communication, commitment, and the setting of shared objectives.

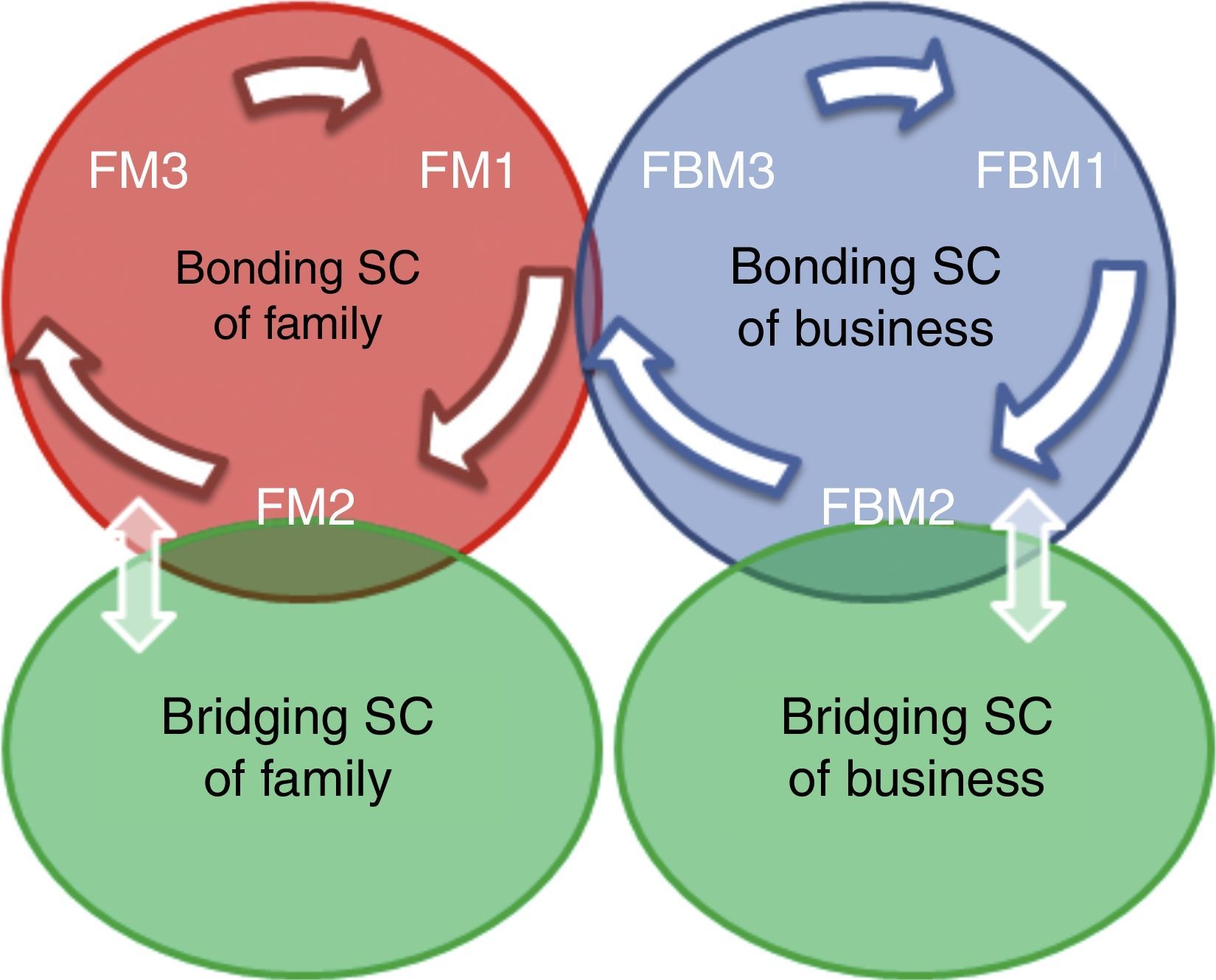

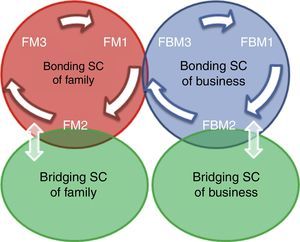

However, the contributions of Sharma (2008) enable us to deepen the relational dimension of familiness defined by Pearson et al. (2008). Thus, Sharma (2008) broadens the focus of analysis from inside the FB to outside – and includes the interactions of the family and the FB with the environment. Social capital is broken down into different types that reflect: how it is configured within the family (bonding social capital of the family); how it develops inside the FB (bonding social capital of the business); the result of family relations with external actors (bridging social capital of the family); or the result of relations of the FB with external actors (bridging social capital of the business) (see Fig. 4).

This paper considers the unit of analysis of the FB as an open system in which the family, business, and individuals are configured as subsystems with their own personality and in continuous interaction with the environment. In these interactions, inputs are received and outputs are created through relationships and the establishment and access to networks. These interactions encourage the creation, access, and use of resources and capabilities configured within familiness that are decisive in gaining a competitive advantage (or disadvantage).

Components and elements of familinessAfter reviewing the literature, in this section the composition of familiness is proposed in response to the call by Pearson et al. (2008). The composition is viewed from the perspective of social capital and open systems, given that social capital can replace other resources (such as the shortage of human and financial capital) because of ‘superior’ connections. Social capital can complement other forms of capital by reducing transaction costs and improving efficiency (Gordon & Cheah, 2014). In addition, unlike tangible capital, the various manifestations of social capital (arising from interactions among individuals and/or groups) are characterised by being attached to and specific to the individual, and are therefore difficult to transfer or exchange (Sharma, 2008). This argument reinforces the importance of the interaction of the individual system as an intangible resource in the analysis of the composition of familiness (as detailed below).

Proposed composition of familinessFollowing the suggestions of Pearson et al. (2008), Sharma (2008), and Zellweger, Eddleston, and Kellermanns (2010) on future research, this paper proposes a composition of familiness that considers: family capital, bonding social capital of the FB, and bridging social capital of the FB.

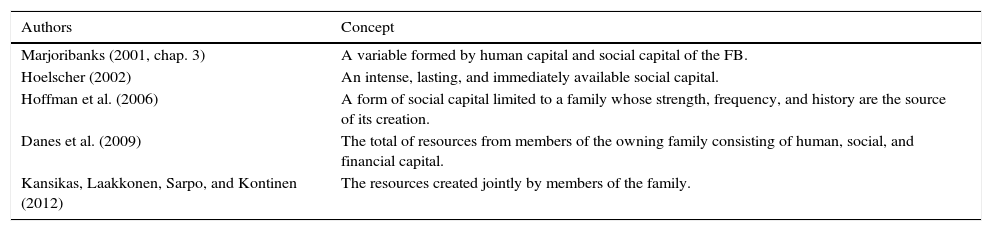

Family capital (FC): identification and reciprocal altruismThe term family capital (FC) has been used in many studies on FB but there is no consensus as to conceptualisation. Table 1 shows how various authors have used the term.

Family capital concepts.

| Authors | Concept |

|---|---|

| Marjoribanks (2001, chap. 3) | A variable formed by human capital and social capital of the FB. |

| Hoelscher (2002) | An intense, lasting, and immediately available social capital. |

| Hoffman et al. (2006) | A form of social capital limited to a family whose strength, frequency, and history are the source of its creation. |

| Danes et al. (2009) | The total of resources from members of the owning family consisting of human, social, and financial capital. |

| Kansikas, Laakkonen, Sarpo, and Kontinen (2012) | The resources created jointly by members of the family. |

Family capital is part of the structural dimension of familiness in Pearson et al. (2008), and is understood as social interactions among members of a group, the density, and connectivity of these ties, and the ability of those members to use and reuse the social connections that may be appropriate, or used for other purposes (Hoffman, Hoelscher, & Sorenson, 2006) in different units. Carr, Cole, Ring, and Blettner (2011) consider this structural dimension as the way in which people can perceive being part of a network of connections. This is capital created by people and the organisational structure of the business that creates a sense of belonging, and this capital may lead to additional resources (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998), or the ability to build capabilities and organisational processes.

These ties among individuals may provide the structure to access additional benefits such as emotional support and identification with the group (Oh, Labianca, & Chung, 2006). This identity is defined as the meaning that family members give to the family for internal processes of self -confirmation (Zellweger, Nason, Nordqvist, & Brush, 2013) and is the principal statement of a family character in a social context (Stryker & Burker, 2000). Thus, identity is configured as an instrument of self-definition of organisations that forms a central, durable, and distinctive element of a group and which allows the group to be distinguished from others (Bingham, Dyer, Smith, & Adams, 2011).

Sundaramurthy and Kreiner (2008) argue that the specificity of the identity of the family within the FB is extremely difficult to copy by competing businesses, and forms part of the firm's ability to create competitive advantage. If this identity is used to support the business, then it can create and maintain this advantage.

Zellweger et al. (2010) analysed how familiness may vary between firms using organisational identity as a key dimension of this variable. In addition, this identity captures the perception that a family has of the business when responding to the question ‘Are we a family business?’ and so directly recognises those families who are more likely to create familiness. Thus, Zellweger and Kellermanns (2008) provided preliminary results suggesting that identity within an FB explains significant variances in business performance.

Gómez-Mejías, Tàkacs, Núñez-Níquel, Jacobson, and Moyano-Fuentes (2007) consider that the identity, family influence, and permanence of the family dynasty are key to satisfying the emotional needs of the family and this leads to certain behaviours by FBs.

Reaching similar affirmations, Berrone, Cruz, and Gómez-Mejía (2012) highlight how the family is tied to the business that normally carries the family name. Internally, it this is likely to have a significant influence on employees and other internal processes and the quality of services and products supplied (Carrigan & Buckley, 2008; Teal, Upton, & Seaman, 2003). Externally, this makes family members more sensitive to the image they project to clients, suppliers, and other stakeholders (Micelotta & Raynard, 2011).

Because of the need to include behavioural variables, it is necessary to resort to theories that explain behavioural variation between companies, such as the stewardship theory.

This theory is used as an alternative to the agency theory to explain the relationship between owners and managers (Vallejo, 2009). Thus, stewardship theory argues that family members are servants of their organisations and are therefore motivated to achieve organisational goals and maximise business development in sales growth and profitability (among other objectives). The family is a resource of the FB when members of the organisation work in favour of it and when they can be trusted (Davis, Schoorman, & Donaldson, 1997). Strong links encourage family members to act as stewards and create conditions conducive to ethical behaviour in the family and, by appropriation, in the FB.

Stewardship is embodied in this type of business (Zahra, 2003) in reciprocal altruism, through a greater dedication of its members to the business and the belief that they have a common family responsibility to succeed (Cabrera-Suárez, De Saá-Pérez, & García-Almeida, 2001). Thus, the devotion that an FB gives to its employees (with the family hoping that this devotion is reciprocated) is such that a dedicated and motivated workforce is configured as an intangible and inimitable resource for family businesses (Miller, Lee, Chang, & Le Breton-Miller, 2009).

Thus, altruism converts employees into ‘de facto owners’ (Schulze, Lubatkin, & Dino, 2003), and so enables an accumulation of social capital that becomes a specific emotional variable of FB (Berrone et al., 2012).

However, family businesses are a heterogeneous group and it is expected that those with a high degree of altruism have high levels of communication and cooperation (Daily & Dollinger, 1992; Simon, 1993), and this strengthens the interdependence of family members and the strength of family ties (Corbetta & Salvato, 2004). Conversely, when the level of altruism is low the possibility of opportunistic behaviour increases alongside the creation of conflicts within the FB (Eddleston & Kellermanns, 2007). Such a lack of altruism may threaten family ties and damage decision-making and communication within the family (Gersick, Davis, Hampton, & Lansberg, 1997; Lubatkin, Schulze, Ling, & Dino, 2005).

This reciprocal altruism between family members may explain why some family business members can work together successfully, while members of other families are full of resentment with everyone demanding rights to the point that business development deteriorates (Kellermanns & Eddleston, 2004). This leads to the following proposition:Proposition 1

Identity and reciprocal altruism are configuring variables of family capital in an FB.

The composition of FC is based on two dimensions (identity and reciprocal altruism) whose positive aspects help produce a competitive advantage over family businesses that have less of this type of capital, or non-family firms (Danes, Stafford, Haynes, & Amarapurkar, 2009).

However, strong group identification can block and stall the development of an FB by producing hostility to new ideas or the incorporation of people from outside the family, and so causing a lack of professionalism and a shortage of talent. Conflicts between family members (Arrègle & Mari, 2010) can also be reduced by the presence of altruism in the organisation (Eddleston & Kellermanns, 2007). These issues shape the more negative aspects of FC that could influence ownership and management structures, as well as the strategic development of an FB.

Nevertheless, altruism may encourage a participatory strategic process by family members in the business, as there are strong ties among them, as well as trust, loyalty, and a sense of shared responsibility (Kepner, 1991). Zahra (2003) argues that altruism encourages family members to ‘work together in defining the mission of the company, designing its strategy, and developing effective ways to achieve goals’. These arguments lead to the following proposition:Proposition 2

Family capital in a business influences the configuration of its familiness.

Bonding social capital (BSC): shared goals and long-term orientationThere is little in the literature that analyses bonding social capital (BSC). Arrègle et al. (2007) discuss the formation of FB social capital from the social capital of the family because of isomorphic business practices with respect to the institution of the ‘family’, and which Pearson et al. (2008) consider the ‘appropriable organisation’. These authors understand that interactions between the individuals within an FB provide ‘meaning’ to the firm. This argument is supported by Sharma (2008) who makes explicit reference to the bonding social capital of an FB as an intangible resource obtained by an FB from internal interactions among members.

While there are many studies on the economic and non-economic objectives of FBs (Argota & Greve, 2007; Astrachan & Jaskiewicz, 2008; Chrisman et al., 2005) and on the differentiating criteria between family and non-family businesses (Chrisman, Chua, Pearson, & Barnett, 2012), there is a shortage of articles in the literature that focus on the importance of these objectives being shared by all members of the business: family and non-family. Thus, when a business has a high level of family resources and transaction costs are low, these goals are shared by both the owners and managers of the business: thereby eliminating problems of agency (Lambrecht & Lievens, 2008). However, these agents do not always coincide within the business.

Thus, the shared mission of the business by family members (Zahra, 2003) is configured as a mechanism of emotional attachment that enables communication to be increased and ideas to be shared and integrated (Tsai & Ghoshal, 1998) and this must be present in the family unit before it can be used in the FB. When its members accept shared responsibility and objectives, it is more likely that business strategies will be effective (Ensley & Pearson, 2005). Families who embrace a collectivist orientation describe their behaviour as a search for the benefit of a larger group – the FB (Bingham et al., 2011).

It has been shown that family members are more committed to their organisations and have higher growth expectations than members of non-family businesses (Beehr, Drexler, & Faulkner, 1997). High levels of involvement by family members create a sense of psychological ownership that motivates the family to behave and act in the best interests of the business (Eddleston & Kellermanns, 2007; Zahra, 2003). According to Eddleston and Kellermanns (2007) reciprocal altruism is crucial to the pursuance of collective goals, given that members exercise self-control and consider the effects of their actions on the business (Corbetta & Salvato, 2004; Kellermanns & Eddleston, 2004), resulting in opportunistic risk reduction, as well as more trust and cooperation (Peng & Beamish, 2014).

However, the objectives of family businesses are usually numerous, complex, and likely to include non-economic objectives to create value through the generations (Chrisman et al., 2003). This type of business therefore includes economic and non-economic goals for profitability, sales growth, market penetration, improved business image, greater customer loyalty, self-reliance, the creation of jobs for family members, and so on. These are the non-financial aspects that Gómez-Mejías et al. (2007) considered as socioemotional wealth (SEW).

Various studies have analysed the non-economic goals of the family and emphasised autonomy and control (Olson et al., 2003; Ward, 1990); cohesion, support, and loyalty of the family (Sorenson, 1999); harmony, sense of belonging, and trusting relationships (Sharma & Manikutty, 2005); pride (Zellweger & Nason, 2008); recognition for the family name, respect, status, and benevolence for the community (Tagiuri & Davis, 1992); as well as security and protection, job creation for family members, and long-term survival of the FB. In short, specific objectives for creating value in these businesses (Mignon & Ben Mahmoud-Jouini, 2014) can be shared by all its members and will enhance the endowment of BSC.

In creating bonding social capital for the FB, the strengthening of emotional ties acts as a stimulus to define the objectives shared by all members of the business. In the establishment of common objectives, long-term orientation implies less pressure to achieve short-term results and more attention on business longevity (Dunn, 1995), since the values of the family are transferred to the FB (Brice & Richardson, 2009). Family businesses can only ensure continuity by having a ‘shared dream’ that embraces the aspirations of the oldest and youngest generations so that the energy and enthusiasm the family needs to ensure survival can be generated (Vallejo & Langa, 2010). Therefore, long-term orientation (Zahra, Hayton, & Salvato, 2004) is configured as one of the competitive characteristics of these businesses (Basco, 2010) because short-term returns are not required and decisions are based on the BSC of the firm (Berrone et al., 2012).

Danes et al. (2009) conclude that in the long-run, social capital plays a more important role than the combination of human and financial capital in the perception of success and so encourages members of the FB to work to achieve the objectives of the organisation. Collective effort and results lead to a shared vision and serve to minimise opportunistic and individualistic behaviour (Ouchi, 1980).

This temporality is manifested in FB with patient capital investments intended to perform over the long rather than short-term; and survival capital which represents accumulated personal resources that family members are prepared to lend or share with the FB to increase or encourage the success of the business (Sirmon & Hitt, 2003).

Thus, it is considered that the variables of shared objectives and long-term orientation represent the cognitive dimension of the model proposed by Pearson et al. (2008). These shared representations and systems of meaning between members of the FB result in lasting bonds that influence behaviour, and determine a degree of cooperation, trust, communication, commitment, and the setting of common objectives. This leads to the following propositions:Proposition 3

Shared objectives and long-term orientation are variables that form the bonding social capital of an FB.

Proposition 4The BSC present in a business influences the configuration of its familiness.

Bridging social capital (BRSC): market orientation and relations with stakeholdersAn FB and family are open systems that interact with their environment and develop lasting relationships with clients, suppliers, and state organisations (among others) (Huybrechts, Voordeckers, Lybaert, & Vandemaele, 2011), and configure the bridging social capital (BRSC) analysed in this section.

An FB may build effective relationships with suppliers, clients, and stakeholders that enable it to obtain resources from these networks or connections (Sirmon & Hitt, 2003) and so create BRSC. This type of capital focuses on direct and indirect external links of any agent (an individual, group, or organisation) with other agents beyond the immediate group. These links facilitate the achievement of objectives by acting as a ‘bridge’ between the main actor and other resources – such as access to capital, information, and markets. This process typically enables the identification of productive opportunities, enables advice to be obtained for business operations (Lester & Cannella, 2006), as well as information for positioning in terms of power and influence (Burt, 1997).

The long-term orientation that characterises family businesses can lead to a market orientation that enables cooperation among groups – so enabling inequalities to be overcome. This action may encourage tolerant behaviour (Nordstrom & Steier, 2015). Such an orientation can be seen as a cultural feature of FB and lead its managers and employees to worry about quality and how to deliver superior value to clients. A high-level of interest in quality is a key factor for achieving a sustainable competitive advantage through customer satisfaction and the maintenance of a good image in the area in which the firm works – as well as improving product quality and prompting the continuous pursuit of customer satisfaction (Tokarczyk, Hansen, Green, & Down, 2007).

These actions generate good reputation, a resource that can lead to gaining a competitive edge. Within this approach are the relations the FB maintains with clients and suppliers, many of whom can be considered as almost family members (Berrone et al., 2012).

Businesses with a high level of social capital are willing to explore new ways of operating in the market because social capital and relationships within networks help reduce the costs of searching for information (Huybrechts et al., 2011). Similarly, social capital can detect business opportunities and this favours the long-term survival of the business (a key goal in family businesses). In fact, the founder of the business can easily study the market situation and work to ensure that the business matches the needs of the market (Lester, Maheshwari, & McLain, 2013). In this way, market orientation drives behaviour that influences the establishment of the strategic business direction and so reflects the qualities that characterise familiness.

In this way, value is created for clients and additional benefits include building trust with clients and flexibility in decision-making (Tokarczyk et al., 2007). Ultimately, bridging social capital will be created and for this to become a source of competitive advantage in the long-term, it needs to be transferred and managed efficiently (Steier, 2001). This BRSC forms a key part of the familiness variable.

It is relevant to include relations with stakeholders as an integrating relational resource of bridging social capital in an FB as it is likely that family bonds also create strong social ties with the whole community (Berrone et al., 2012) where a family business is deeply embedded. In fact, these businesses often found associations and sponsor local charitable and sporting activities. Moreover, when an FB performs some type of social action in the community, it develops a set of values that pervade the family and business unit.

That is, these organisations carry out corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities driven by the wish to improve the welfare of all those who surround the business, even if there is no transactional financial gain in doing so (Brickson, 2005, 2007). These actions generate social capital and are institutional responses that heighten the chances of survival and generate prestige for the FB (Le Breton & Miller, 2013). These arguments lead us to state the following proposition:Proposition 5

Market orientation and relations with stakeholders are variables that configure the bridging social capital of an FB.

Families have unique advantages in developing BRSC between themselves and the stakeholders of an FB (Cabrera-Suárez & Olivares-Mesa, 2012). This bridging capital shapes the relational dimension of familiness. It is thus seen that both the family and the business generate networks for the benefit of the firm and this action creates advantages in terms of brand and reputation; as well as advantages in terms of emotional and financial value because the family can use both types of assets to help the business (Tàpies, 2011). The social capital of the family and the social capital of the FB are interconnected because the family can normally expand its structure and benefit the organisation through relational trust and feelings of closeness and solidarity (Berrone et al., 2012). In addition, transfers of information and resources between the family and the business can occur (Carr et al., 2011), which is what Pearson et al. (2008) called ‘appropriable organization’ since the FB uses the resources created in the family to achieve its goals. This leads to the following proposition:Proposition 6

Bridging social capital within the business influences the configuration of its familiness.

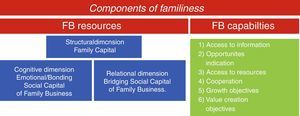

Thus, the arguments explained so far lead to the composition of familiness shown in Fig. 5.

This work examines the composition of familiness, a variable that is widely used in the literature on FB, but which is often approached through proxy variables that are more easily observed and measured. Thus, from the definition of familiness given by Habbershon and Williams (1999), an analysis from the social capital perspective of Pearson et al. (2008) and Sharma (2008) and considering the FB as an open system, we have established a series of propositions regarding the composition of the concept of familiness. Once the proposed theoretical model has been verified and validated, these propositions will enable the measurement and evaluation of the relationship of familiness with competitive advantage (and disadvantage) for FBs in general (when compared with other types of companies), or for specific types of FBs.

We introduce the constituents of social capital in the family unit, its relevance to the social capital of an FB, and how this social capital is determined by the ‘bridge’ relations between the family and the FB and their environments. The familiness of an FB is configured by family capital, bonding social capital, and bridging social capital.

In turn, each of these capitals is set by variables that have been drawn from a review of the literature. Thus, family capital in a business depends on the identity and reciprocal altruism within the business. Bonding social capital is determined by shared goals and long-term orientation. Finally, bridging social capital is configured by market orientation and stakeholder relations.

The theoretical framework used in this article has led us to propose this composition of familiness (a concept difficult to observe and measure) by making a series of theoretical propositions that require empirical testing. Future work should follow an inductive method and/or apply quantitative methodologies to throw light on the proposed composition of familiness and make measurements. This approach will clarify the presence, or otherwise, of this construct within firms, its type, and establish what endowment of familiness leads to a competitive advantage (or disadvantage) in FBs.

The limitations of the established propositions and theoretical model include the possibility that the heterogeneity of family businesses, as well as their distinct cultural contexts and sectors of activity, may influence in their endowments of familiness.

Finally, among the practical implications and recommendations for management, it is worth highlighting that the proposed model and defined components enable ‘measuring’ the endowment of familiness in an FB – and so ‘managing’ this construct with the aim of finding guidelines for increasing competitiveness. Firms with a limited availability of other types of resources can ‘encourage, develop, and nourish’ familiness to enhance business growth.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.