Retention of doctors had been a big challenge for Ethiopian public hospitals. Private wing service in public hospitals was established in Ethiopia in 2009 with major objectives of retaining specialist doctors and improving access to health services.

ObjectiveThis study was conducted to assess the effectiveness of the private wing services in St. Paul Hospital.

MethodsQualitative and quantitative data were collected in January 2016. Focus group discussions, key informant interviews and documents review were conducted. A total of 37 participants were included in the study. The discussions and interviews were conducted with specialist doctors, nurses, anesthetists and members of the hospital management team. Consent was obtained from all participants before the data collection. All data were transcribed verbatim, typed and stored safely. Then content and thematic analysis was conducted.

ResultsMost of the participants agreed that the private wing arrangement had contributed to the motivation and retention of specialist doctors most notably the surgeons in the hospital. The number of specialist doctors in the hospital increased over the 6 years after the establishment of the private wing by 223%. Most participants mentioned that the hospital benefitted from the private wing. The number of major surgeries conducted in the regular service of the hospital increased by four folds over the six years. In the same period, a total of 8,975,967 ETB was generated to the hospital.

ConclusionThe private wing in St. Paul hospital was successful as it contributed to the retention and motivation of specialist doctors and improved access to health services. Other public hospitals may consider establishing private wing services.

It is widely acknowledged that the health work force, as an integral part of health systems, is a critical element in achieving universal health coverage. The migration of health workers to high-income countries has been of great concern to developing countries. Developing countries have particularly suffered from high attrition rates; geographical imbalance and an uneven skill mix of health workers. As a result, achieving universal health coverage has been a big challenge for many developing countries.1 It has also been noted that globalization has an impact on hospital management, in both public hospitals and private nonprofit hospitals, in order to achieve clinical, quality and financial objectives.2

Many African countries have started training more medical doctors to tackle the shortage of medical doctors. However, the rate of brain drain is incomparably high as compared to the rate production. Although many African countries are brain drain victims, the three severely affected ones in descending order are Ethiopia, Nigeria and Ghana. Therefore, because of the complex web of factors that influence the mobility of health workers, any efforts to scale up the health workforce in response to the shortage must be combined with effective measures to attract and maintain existing health professionals.3

Poor remuneration is a feature of many health systems in Africa. This is especially so because most health workers in African countries work for the government and poor remuneration of civil servants helps to reduce public spending. The salaries unrealistically low and the living conditions are not up to the required standards.4 Thus, many African countries tried to improve the remuneration packages of health professionals. In Zimbabwe, for example, a retention package was implemented in for health professionals. The financial incentives were found to be less effective in retaining staff, as they were eroded by high inflation rates. Sometimes, incentives were not uniformly applied to all health workers, and did not always reach all in the target category. In Kenya, for example, the incentives mainly targeted nurses and doctors.5

Even though the Ethiopian government has recognized the need to address the health workforce, migration of medical doctors significantly compromised the quality and access of health care services. Between 1987 and 2006, 73.2% of medical doctors left the public sector mainly due to attractive remuneration packages in other countries, international NGOs and the private sector in the country.6 Despite the rapid expansion of health training institutions and the production of physicians in Ethiopia, the gains made have been offset by brain drain.7

To address the high attrition rates of medical doctors, the government of Ethiopia approved the establishment of private wing services in public hospitals in 1998 as part of the health sector reform. Then, implementation of the private wing arrangement in public hospitals was launched in 2008.8 Establishing private wing in public hospitals is one of the options for private participation in hospitals recommended by the World Bank.9

The main objective of establishing private wing in public hospitals in Ethiopia is to increase motivation and reduce attrition rates among health workers especially specialist doctors. Other objectives are to improve the quality of services; to mobilize additional resources and to subsidize the public ward; and to provide alternative care access for clients. Private wing is an official arrangement where medical services are provided, on a fee for service basis, to inpatient and outpatient clients in public hospitals. Doctors and other health workers get additional income for providing services to the private clients in public hospitals.8

A literature review indicated that establishing well functioning private wings in public hospitals can result in retention of staff, increased client satisfaction and increased revenue flow to the hospital.10 A study conducted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia revealed that medical professionals had the intention to continue working in government health facilities at least for three more years indicating a positive outcome of the private wing arrangement in public hospitals in retaining medical professionals.11 A study conducted in Tygerberg Academic Hospital, Johannesburg, South Africa, revealed that the existence of private wards in public hospitals could increase revenue flow to the hospital to improve the quality of service in public wards.12

However, there is a significant research gap regarding the effectiveness of the private wing arrangement in Ethiopia. The effectiveness of the private wing arrangement in achieving the set objectives has not been studied to the researchers’ knowledge. Therefore, objective of this study was to assess the effectiveness of the private wing arrangement in St. Paul Hospital Millennium Medical College (SPHMMC) in achieving the set objectives.

MethodsThe study was conducted in St. Paul Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia from December 2015 to January 2016. Guided focus group discussions (FGDs) and key informant interviews (KIIs) were used to collect qualitative data. Relevant documents were also reviewed for additional qualitative and quantitative data.

The key informant interviews (KIIs) were conducted with purposively selected relevant managers in the Hospital based on their role in the management of the private wing: the Provost, Vice Provost for Medical Services, the Acting Vice Provost for Administration and Development and the Private Wing Coordinator. Participants of the focus group discussions (FGDs) were selected randomly from those departments that provided private wing services. Nurses, specialist doctors and anesthetists the relevant departments participated in the FGDs. Accordingly, a total of 4 key informant interviews and 4 focus group discussions were conducted. A total of 33 health professionals participated in the four FGDs. Reviewed documents include the National Private Wing Guideline; St. Paul Hospital Private Wing Financial Reports; the profile of doctors per speciality (obtained from the Planning Department of the Hospital); and the annual number of major and minor surgeries conducted (obtained from a document shared by the Planning Department).

The proposal was submitted to the institutional review board (IRB) of St. Paul Hospital Millennium Medical College (SPHHMC) and ethical approval was obtained. Oral consent was obtained from all interviewees and participants of the FGDs. The recorded interviews were used only for the purpose of the study and were deleted at the end of the research project.

A team of an experienced researcher and a public health specialist conducted the interviews, facilitated the FGDs and conducted the document reviews. The audio-recorded interviews and FGDs were transcribed. Then content and thematic analysis was conducted. For each transcription, issues relating to the study objectives were identified and coded without predefined categories. After the completion of the coding process, themes were developed and classified. A triangulation of data sources and methods were employed, comparing information from different respondents, different methods (KIIs and FGDs) and reviewed documents.

ResultsOverview and respondents profileThe provision of private wing services was started in 2009. The major services provided in the private wing include consultation, laboratory testing, imaging services, minor and major surgeries and inpatient care. Among the 17 clinical departments in the hospital, 12 departments were providing the services by January 2016.

A total of 37 health workers participated in the study. Thirteen were females while the remaining were males. Four of them participated in the key informant interviews while the remaining 33 were participants of the focus group discussions (FGDs). Out of the 33 who participated in the focus group discussions; 13 were specialist doctors, 14 were nurses and the rest 6 were anesthetists. Out of the 13 specialist doctors who participated in the FGDs, 9 of them were used to perform procedures/surgeries.

Familiarity with the objectives of the private wingKey informants were familiar with most of the objectives of the private wing. All the key informants mentioned at least two objectives of the private wing establishment by the Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) of Ethiopia. All of them were aware of motivating and retaining specialist doctors was the primary objective of private wing services.

The focus group discussants mentioned most of the objectives of the private wing establishment in the country. Motivating and retaining specialist doctors was mentioned as a primary objective of private wing in all the FGDs. A female nurse said, “Can I speak what I am feeling? The private wing service is established for the benefit of doctors. It is designed to retain and motivate doctors.” Improving access to services to clients at reasonable price; motivating and retaining other health workers; and reducing the burden on the regular medical services were mentioned by the study participants as objectives of the private wing.

Motivation and retention of health workers in the hospitalAll the key informants and FGD participants agreed that the private wing arrangement motivated, retained and attracted specialist doctors. This was true especially for those who were performing procedures/surgeries. They also mentioned that the hospital managed to keep most of its specialist doctors while the number of employment applications increased. Some of the key informants mentioned that health professionals working in the radiology department and anesthetists were also benefited from and motivated by the private wing arrangement. Anesthetist FGD discussants said that most health workers were benefitted from the private wing arrangement including the support staff. They argued that though the payment is small, the private wing arrangement benefited most health workers in the hospital.

However, both key informants and FGD participants mentioned that the effect of the private wing arrangement in the motivation and retention of other health professionals and administrative staff was not that significant. This was because a small proportion of the revenue from the private wing services were divided among other health professionals. Especially nurses were not motivated by the arrangement as they were dissatisfied by the payment they were getting for participating in the private wing services. One nurse FGD participant said, “Nurses prefer to work in private clinics as they can get more money. Nurses are not motivated. There is a high turnover rate of nurses in the hospital.”

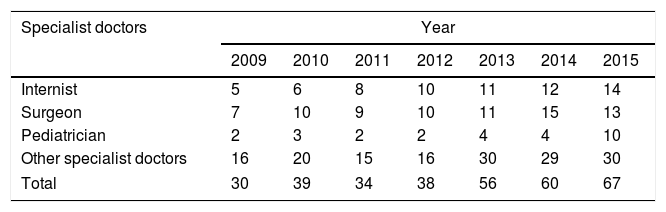

Document review revealed that the number of specialist doctors in the hospital had increased by 223% from 30 in 2009 to 67 in 2015 over the 6 years after the establishment of the private wing (see Table 1).

Total number of specialist doctors in the six years after the establishment of private wing services in St. Paul Hospital, January 2016.

| Specialist doctors | Year | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

| Internist | 5 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 14 |

| Surgeon | 7 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 15 | 13 |

| Pediatrician | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 10 |

| Other specialist doctors | 16 | 20 | 15 | 16 | 30 | 29 | 30 |

| Total | 30 | 39 | 34 | 38 | 56 | 60 | 67 |

Key informants and FGD participants had mixed opinions on the quality of the private wing services.

Some key informants said that the quality of private wing services was very good as experienced specialists provided services and clients were provided with timely medical and surgical treatment. Clients had the right to choose the specialist they wanted to get service from and this increases their satisfaction. Clients were not required to wait for a long period of time for surgical interventions. However, one key informant revealed that clients had hard time making payment for services, which affected their satisfaction. He said, “There is no separate triage/card room for the private wing clients. The waiting area is overcrowded especially after 5:00 PM. Payment is a problem; two payment receipts are issued for the client, one for the surgeon and the other for the hospital. The location of card room and outpatient department (OPD) is not adjacent and some departments are located far from the card room.”

Other key informants felt that the quality of private wing medical services was not better than that of the regular medical services. The services were provided with the existing medical equipment and materials. The facilities were the same in both private and regular service, and nursing care was provided in a similar fashion. They also felt that clients expectations were not fulfilled regarding post surgery follow up. Clients expected to be followed by the surgeon who performed the surgical operation but sometimes the surgeon might delegate other surgeon or residents to follow the patients post surgery. Sometimes, follow up problems could happen even in the out patient department. Specialists provide consultation services and order various examinations. When the patient comes back on the next day with the examination result, the specialist doctor might not be available.

In the FGDs, most specialist doctors agreed that the quality of the private wing medical services was not up to the standard. They mentioned the following reasons for considering the quality of the services to be substandard.

- •

The post operative follow up was poor particularly in weekends.

- •

The private wing services were not reported while the regular services were reported in the morning sessions. There was no system for follow up and reporting of the private wing cases. Audit report was also not in place in the private wing.

- •

Major surgeries were performed by fewer number of team members in the private wing while in the regular services at least three professionals were involved in each major surgery. In the regular program a surgeon and two assistants (residents) operated on a patient while in the private wing a surgeon and only one assistant (mostly nurses) operated on a client.

- •

Patient history was not taken and recorded properly; the specialists wrote no preoperative note or preoperative order. In the regular program the specialists write orders on patient charts to be executed by the nurses. The specialist was expected to take and document patient history that was not practical in many instances.

Some specialists mentioned that the only advantage of the private wing arrangement to the clients is that clients could get the services without waiting for a long period of time. A specialist doctor said, “If your definition of quality is short waiting time, there is no long queue in the evening but the clinical service is the same both during the day and in the evening. Nothing more, except the number of clients admitted in private wing (in the evening) may be fewer than that of the regular services (during the day time).”

Most of the nurses perceived the quality as poor except the services provided by the radiology unit where the services were getting improved due to high tech equipment like magnetic resonant imaging (MRI) and qualified radiologists who had joined the hospital lately. The number of beds in the private wing was limited and even if clients got bed there was no proper follow up of patients especially compared to private health facilities. Nurses were not working hard especially in the ward due to low payment. One nurse said, “If you go to private clinics the nurses ‘sneeze’ when the patient ‘sneezes”’.

The nurses mentioned that, once the patient had the operation, doctors were not coming back immediately to see how the patient was doing. The surgeons did not appear though the patients demanded for the visit of the specialist doctor who operated on them. They often came the following day and follow up in the weekends was particularly poor. There was no schedule for regular post-operative follow up by the specialists. Some specialists gave instructions regarding the patient through telephone. On the other hand, clients were not pre-informed or oriented about the services and they did not know what, how, where, from whom they receive the services especially after the operation. As a result, some clients were dissatisfied with the services and angry with the providers.

Anesthetist FGD discussants agreed that the quality of the private wing services was good. The clients could choose the specialist doctor who provide them with the required services. The private wing bedrooms were better than that of the regular bedrooms as they were less crowded with patients. The patients got the services within a short period of time as compared to the regular services with reasonable payment. However, few anesthetists considered the private wing service quality was similar to that of the regular services.

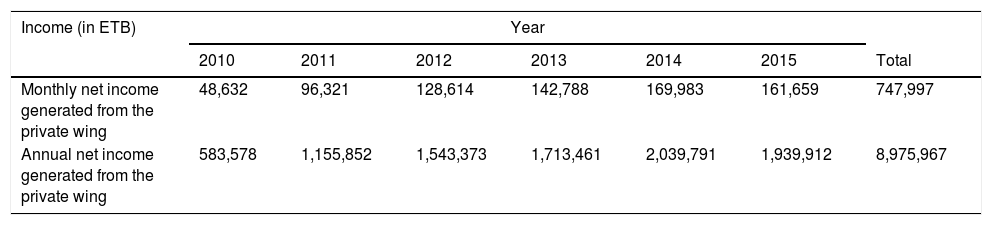

Revenue generation to the hospitalOver the six years period after the establishment of the private wing, a net total of 8,975,967 ETB was generated to the hospital. The income generated to the hospital as a result of the private wing arrangement increased from time to time. The net annual income generated to the hospital by the private wing significantly increased by 332% from 583,578 ETB in 2010 to 1,939,912 ETB in 2015 (see Table 2). Key informants mentioned that 15% of the income from the private wing services had been kept as revenue generated for the hospital. Though the hospital could not fully utilize the revenue due to unclear income utilization policy by the Ministry of Finance and Economic Development of Ethiopia, the hospital was courageous enough to purchase reagents, equipment and 6 vehicles for department heads in the hospital. One key informant said, “We bought 6 service vehicles for department heads including the private wing coordinator. This empowers the management to assign capable department heads. That was the turning point of SPHMMC for its current improvement.”

Net revenues generated (to the hospital) from the private wing services in St. Paul Hospital, January 2016.

| Income (in ETB) | Year | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Total | |

| Monthly net income generated from the private wing | 48,632 | 96,321 | 128,614 | 142,788 | 169,983 | 161,659 | 747,997 |

| Annual net income generated from the private wing | 583,578 | 1,155,852 | 1,543,373 | 1,713,461 | 2,039,791 | 1,939,912 | 8,975,967 |

The participants mentioned a number of positive effects on the private wing on the regular health services of the hospital.

Both the key informants and FGD discussants mentioned that the private wing arrangement improved accessibility of specialist doctors in the duty hours including the evening, at night and the weekends. Before the establishment of the private wing, it had been very difficult to find and consult specialist doctors in the evening sometimes even in the afternoon. The specialists used to leave the hospital in the afternoon to work in private health facilities to earn some more money. After the private wing started, specialist doctors stayed in the hospital waiting for their private wing clients in the evening. Whenever they had to conduct procedures or see patients at the OPD, then they would stay in the hospital even at night. This facilitated better care for emergency patients in the regular service at any time including the weekends.

Another positive effect mentioned by both the key informants and FGD participants was that the load on the regular services had been reduced. As many patients were getting treatment in the private wing with reasonable cost, the number of those patients waiting for treatment in the regular service decreased. One key informant related, “Before the private wing service establishment, patients had to wait for three years to get operated. Currently the waiting time has been reduced to three months.”

Most key informants mentioned that efficiency of the hospital had been increased as a result of the private wing establishment. Given the existing facilities more patients were served. One key informant said, “Before the private wing establishment, some surgeries were canceled due to various reasons. After the private wing establishment the number of patients operated per physician increased.” One of the key informants reported that before the private wing establishment gynecology department used to serve 400 clients per month while after the establishment around 1000 clients were served per month. Similarly, the FGD participants felt that the regular hospital services were upgraded and efficiency increased as a result of the private wing establishment.

Another positive outcome of the private wing mentioned by key informants was improvement in the quality of medical education in the hospital. Resident doctors were benefiting from the private wing arrangement as they assist in various procedures in the private wing in addition to those conducted in the regular services. Accordingly, residents had got more exposure to various types of procedures and they would be more competent.

On the other hand, the key informants and FGD participants revealed that the private wing establishment also had a few negative effects on the regular health service provision. Bedrooms were taken from regular service that could affect service provision in the regular ward. There had been conflicts of interest among health workers that brought additional burden to the hospital managers. Complaints were continuously reported as a result of staff dissatisfaction on the private wing arrangement.

One of the key informants noted that health professionals were more motivated and creative in the private wing than the regular services. Knowingly or unknowingly those health providers who benefited from the private wing service showed the tendency to push patients to the private wing service by extending the waiting list of clients for operation in the regular program. He explained, “In some cases, clients are forced to wait for three weeks to get operated in the regular program, but in the private wing service they can get operated within three days for the same health problem. Hence, sometimes clients are forced to use the private wing service though it may not be their preference.” Similarly, the FGD discussants observed a tendency to prioritize the private wing services than the regular services by some health care providers. As a result, working time of the regular services was compromised in some cases. According to the Private Wing Guideline, the private wing services should be provided outside of the working hours. This means, in the working days, the private wing services should be started after 5:00 pm. However, FGD participants mentioned that in some cases services were started before 5:00 pm even before 4:00 pm.

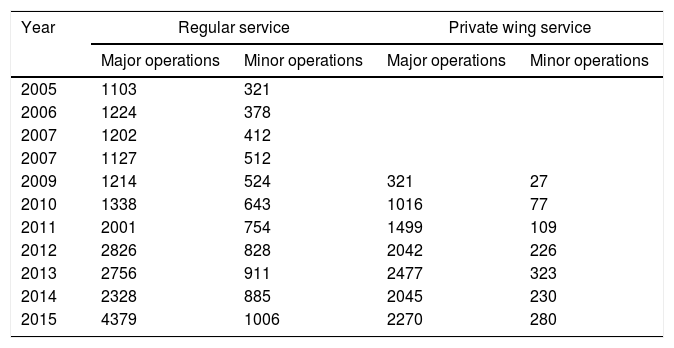

Overall, key informants and FGD participants agreed that the positive effects of the private wing on the regular health services outweigh the negative effects. In addition, document review showed that the efficiency of the hospital improved after the establishment of the private wing. The number of surgeries conducted each year before the establishment of the private wing was compared with the number of surgeries conducted each year after the establishment of the private wing in 2009. It was found out that the number of both major and minor surgeries conducted in the regular service increased every year especially after the establishment of the private wing. The number of major surgeries conducted in the regular service of the hospital increased by four folds from 1214 in 2009 at the establishment of the private wing to 4379 in 2015. The number of minor surgeries conducted in the regular program increased by two folds from 524 in 2009 to 1006 in 2015 (see Table 3).

Average number of surgeries (minor and major) per year before and after private wing service establishment (2009) in St. Paul Hospital, January 2016.

| Year | Regular service | Private wing service | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major operations | Minor operations | Major operations | Minor operations | |

| 2005 | 1103 | 321 | ||

| 2006 | 1224 | 378 | ||

| 2007 | 1202 | 412 | ||

| 2007 | 1127 | 512 | ||

| 2009 | 1214 | 524 | 321 | 27 |

| 2010 | 1338 | 643 | 1016 | 77 |

| 2011 | 2001 | 754 | 1499 | 109 |

| 2012 | 2826 | 828 | 2042 | 226 |

| 2013 | 2756 | 911 | 2477 | 323 |

| 2014 | 2328 | 885 | 2045 | 230 |

| 2015 | 4379 | 1006 | 2270 | 280 |

All key informants mentioned that the private wing arrangement motivated, retained and attracted specialist doctors. This was true especially for those who were performing procedures/surgeries. After the private wing establishment, the hospital managed to keep most of its specialist doctors while the number of employment applications increased. Most focus group discussants agreed with the key informants in that the arrangement motivated and retained specialist doctors who were performing procedures. This was objectively verified as the number of specialist doctors in the hospital had steadily increased over the 6 years after the establishment of the private wing arrangement as per the document review finding. Though we cannot say for sure that the increment in the number of specialist doctors is solely due to the existence of the private wing, we can recognize that the private wing has contributed to the retention of specialist doctors in the hospital. This finding is consistent with a study conducted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia which revealed that medical professionals had the intention to continue working in government health facilities at least for three more years as a result of the private wing arrangement in the public hospitals they practice.11

The income generated to the hospital as a result of the private wing arrangement increased from time to time. The estimated net annual income generated to the hospital by the private wing significantly increased from 583,578 ETB in 2010 to 1,939,912 ETB in 2015. The increment in revenue was more than three folds, which is very significant even in the presence of high inflation rates. Overall, the hospital benefitted from net revenue of 8,975,967 ETB from the private wing over the six years after the establishment of the private wing. A similar finding was reported in a study conducted in Tygerberg Academic Hospital, Johannesburg, South Africa, which revealed the existence of private wards in public hospitals, could increase revenue flow to the hospital.12

The private wing was found to have a number of positive and some negative effects in the regular health services of the hospital. After the establishment of the private wing, specialist doctors were available all the time even at night and weekends for consultation. Patient who could afford were getting treatment in the private wing reducing the workload of the regular program to some extent. Respondents felt that as a result of retention of experienced specialists, the quality of the regular medical services was maintained. All these factors could sum up to significantly improve the quality of medical services provided in the hospital.

Interestingly, the number of both major and minor surgeries conducted in the regular service increased every year after the establishment of the private wing. The rate of increment in the number of both major surgeries is more than that of the rate of increase in the number of surgeons. It seems like the private wing establishment resulted in increased number of surgeries conducted in the regular program due to increased number and efficiency of surgeons. Most notably, in 2015, the number of major surgeries conducted was almost twice that of 2014. This is inconformity that that the hospital claimed that it used the private wing arrangement to motivate the surgeons to perform more in the regular program.

On the other hand, bedrooms were taken from regular service that could affect service provision in the regular ward. There had been conflicts of interest among health workers that brought additional burden to the hospital management. A tendency to give more emphasis to the private wing services than the regular services was observed and as a result working time of the regular services was compromised for the private wing services.

ConclusionsThe private wing arrangement had significantly contributed to the motivation and retention specialist doctors especially those who performed procedures most notably the surgeons. Other health workers like anesthetists and pharmacists were also benefited from and motivated by the private wing. However, it seems like nurses were not happy by the payment they were receiving for providing private wing services.

Access to health services improved due to the establishment of the private wing services providing health care for those who can afford with reasonable price and access to the regular health services was also increased due to increased efficiency doctors especially the surgeons.

Significant amount of revenue had been generated to the hospital as a result of the private wing establishment. The amount of revenue generated had been increasing every year since the establishment of the private wing in the hospital.

The private wing establishment was found to have a number of positive and some negative effects in the regular health services of the hospital. After the establishment of the private wing, specialist doctors were available all the time even at night and weekends for consultation, which improved the quality of services. On the other hand, bedrooms were taken from regular service that could affect service provision in the regular ward.

Therefore, it is recommended that St. Paul Hospital,

- •

Continue providing the private wing services to retain and motivate specialist doctors and improve the quality of services in the hospital.

- •

Dedicate a separate building/ward including consultation rooms, inpatient wards, pharmacy and the card section for the private wing services to mitigate the unfavorable effect of the private wing on the regular services.

- •

The nurses complained a lot about the amount of payment they were receiving. Though it is difficult to satisfy everyone, the payment distribution should be fair. Therefore, the hospital may consider reviewing the payment distribution for fairness and acceptability and make the necessary measures as needed.

- •

Other public hospitals may learn from the experience of St. Paul hospital and consider establishing the private wing services to motivate and retain their doctors and other health professionals.

This work is supported by Millennium Medical College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank the health professionals and key informants who participated in the study. We would also like to thank the data collectors for conducting the key informant interviews and facilitating the focus group discussions. Finally, we would like to thank St. Paul Hospital Millennium Medical College for covering the costs of data collection of the study.