Efforts have been made in recent years to evaluate whether the presence of dilated Virchow–Robin spaces (dVRS) on MRI studies, which had previously been considered incidental, may play a role in such diseases as stroke, multiple sclerosis, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, and Alzheimer disease (AD), and whether dVRS cause any symptoms.

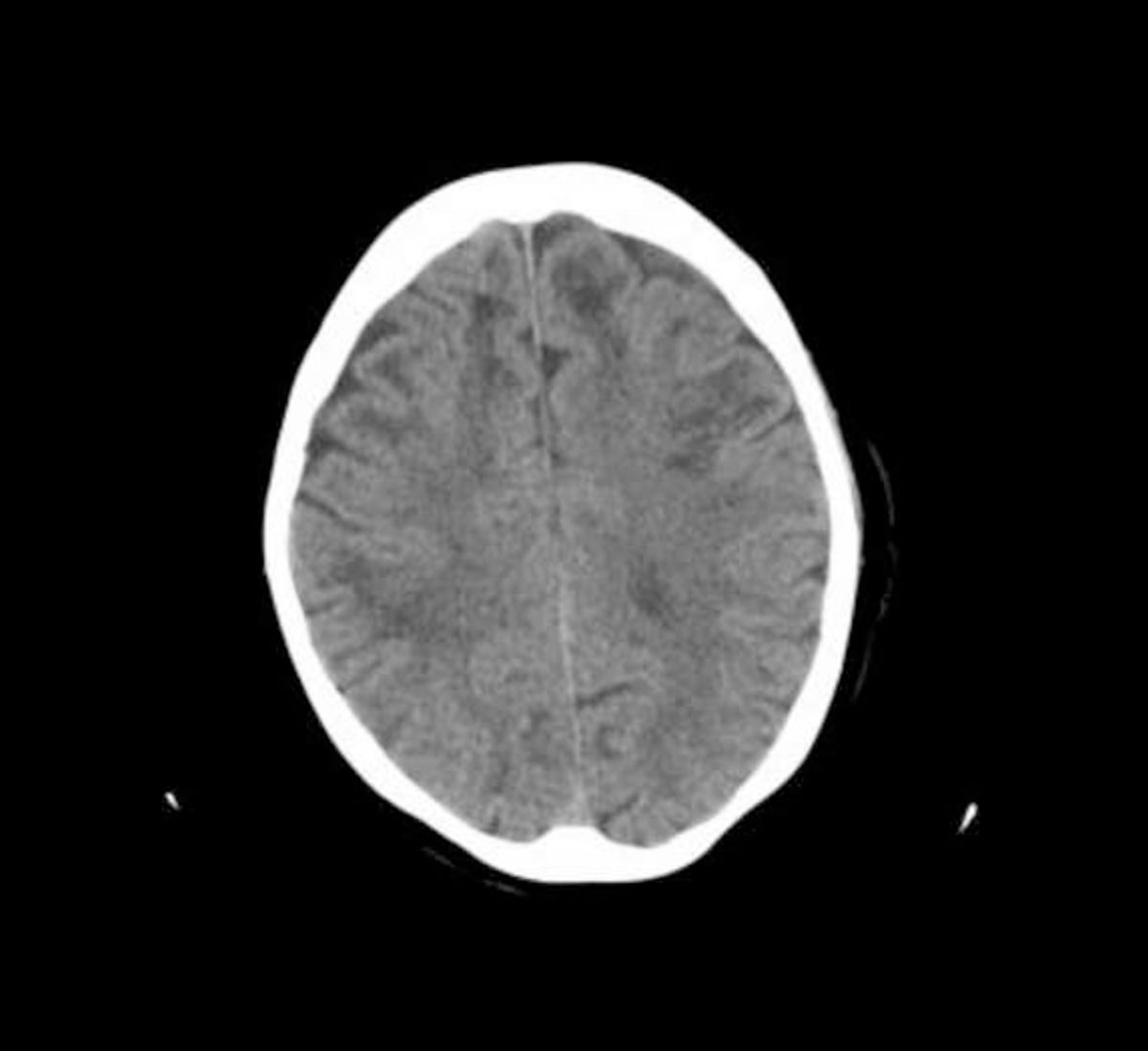

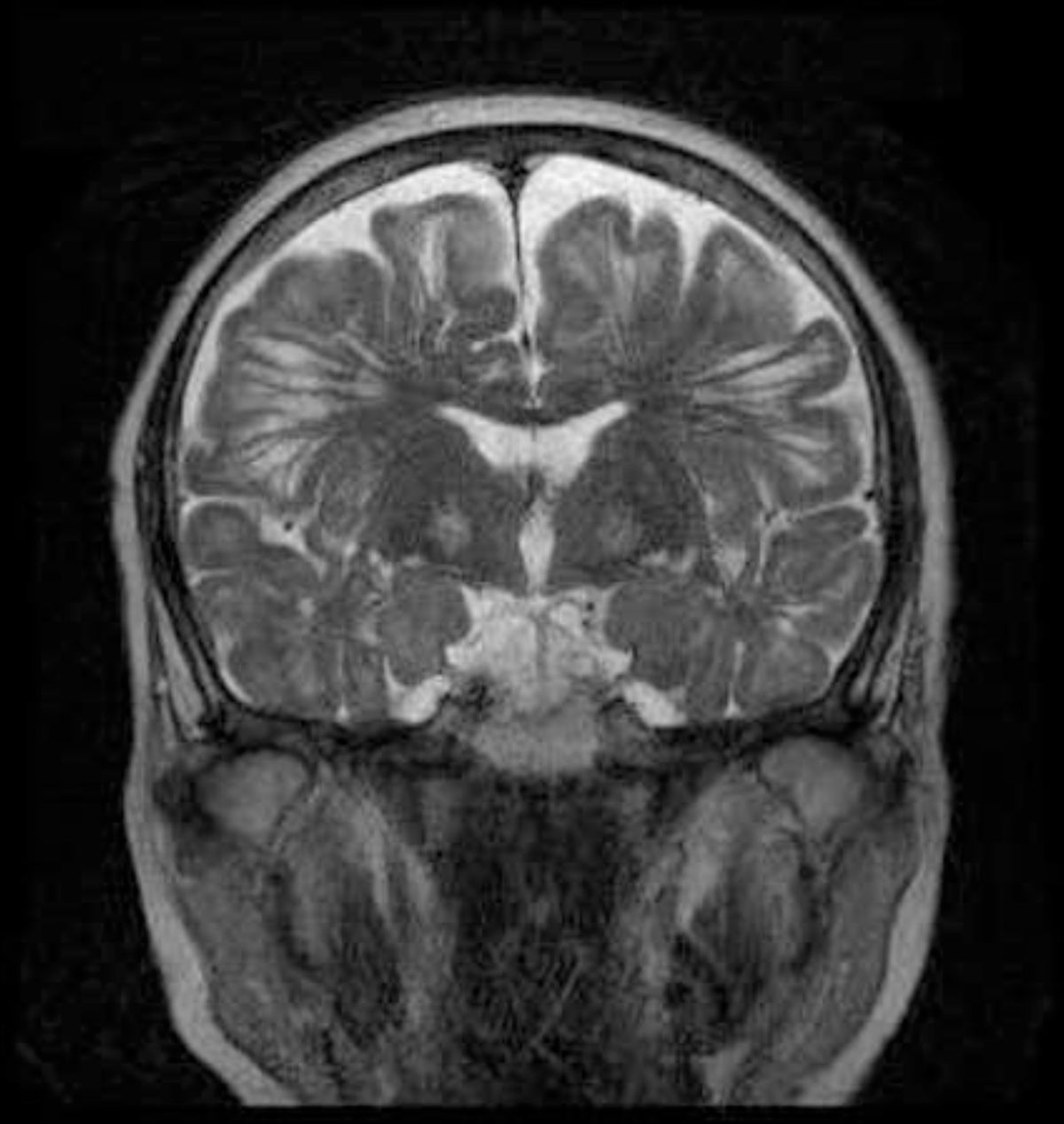

We present the case of a 74-year-old woman with no relevant clinical history, who was assessed due to a 3-year history of progressive cortical cognitive decline with anterograde amnesia, aphasia, agnosia, apraxia, and loss of initiative to perform instrumental activities of daily living, scoring 23/30 on the Mini-Mental State Examination (Folstein, 1975), and presenting mild parkinsonism with reduced arm swing during gait and resting tremor of the right hand. No falls or visual hallucinations were reported. A blood test ruled out treatable causes, and a brain CT scan revealed subcortical hypodense lesions in both hemispheres (Fig. 1). A brain MRI scan showed dilatation of the Virchow–Robin spaces, together with cortical fronto-temporo-parietal atrophy (Fig. 2). In view of these findings, we ruled out hyperhomocysteinaemia and vasculitis and diagnosed probable AD with parkinsonism of vascular origin.

Virchow–Robin spaces are perivascular, interstitial fluid-filled spaces surrounding cerebral vessels passing from the subarachnoid space through the brain parenchyma; they are considered a drainage route for residual metabolites of parenchymatous activity to the subarachnoid space for removal. They are typically located on the lenticulostriate arteries in basal ganglia (type I), perforating arteries of the corona radiata and semioval centres (type II), and brainstem (type III).1 They are considered to be dilated when their diameter is equal to or larger than 1mm. Larger spaces may be detected on CT studies, but MRI provides more specificity on their nature, since they behave in the same way as cerebrospinal fluid. Recent studies associate findings of dVRS with parkinsonism2 and with such neurodegenerative diseases as AD.3 Some authors propose performing a uniform radiological evaluation of the lesion load and localisation before dVRS should be considered predictors of stroke or AD.4 Some interesting studies with animal models have assessed the potential pathogenic mechanism explaining the association between dVRS and AD, suggesting that accumulation of amyloid protein in the vascular walls may occlude the space surrounding them and interfere with perivascular drainage, hindering the passage of beta-amyloid from the interstitium to the subarachnoid space for removal, decreasing clearance of cerebral amyloid and favouring its deposition.5

In our patient, the presence of dVRS on CT is of interest considering the parkinsonism symptoms attributable to them and their implication in AD pathogenesis.

Please cite this article as: Casadevall Codina T, Espada Olivan F, Guerrero Castaño C, Ruscalleda Morell N. Relación de los espacios de Virchow–Robin con la enfermedad de Alzheimer: a propósito de un caso. Neurología. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nrl.2017.07.007