The pathogenic association between Virchow-Robin spaces (VRS) and parkinsonism is unclear.1–11 We present a patient with midbrain VRS and a parkinsonian syndrome, and discuss the pathophysiology of this association.

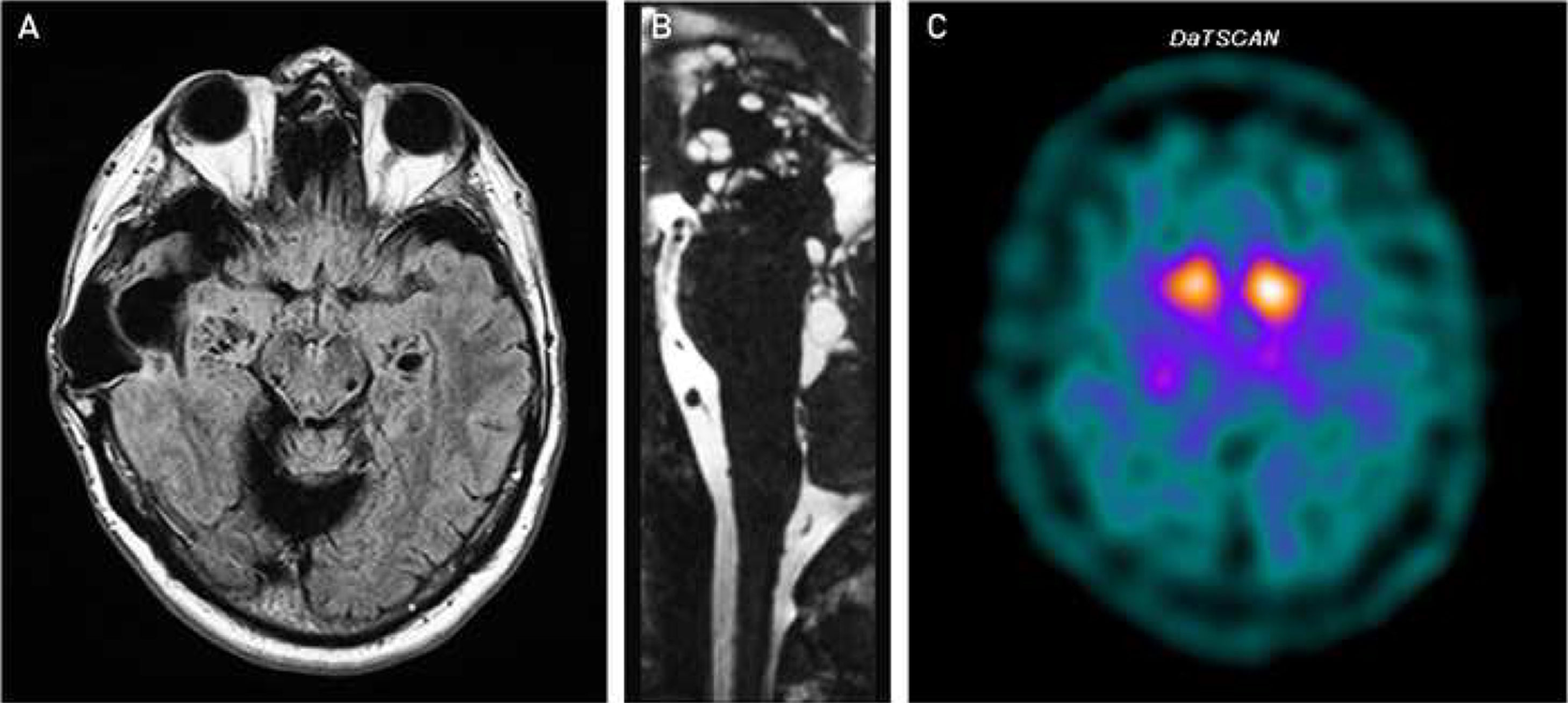

The patient was a 57-year-old man who consulted due to tremor in the right hand, slowness in everyday activities, and more monotonous tone of voice. He had presented tuberculous meningitis at the age of 8 years. Physical examination identified divergent strabismus of the right eye with limitation of adduction, peripheral facial palsy with synkinesis of the orbicularis oris muscle, and hypoacusia; all symptoms were considered to be secondary to previous tuberculous meningitis. He presented mildly inexpressive facies, moderate resting tremor in the right upper limb, mild stiffness and bradykinesia of both right limbs, reduced right arm swing when walking, and normal postural reflexes. A brain MRI study (Fig. 1A and B) detected cystic lesions in the cerebellum, hippocampus, caudal part of the striatum, and bilateral midbrain; the lesions behaved as cerebrospinal fluid on all sequences, and corresponded to perivascular spaces or VRS. Images also showed encephalomalacia of the right temporal lobe and cystic lesions in the fourth ventricle, which were judged to be sequelae of meningitis. A SPECT study with ioflupane (I-123) (DaTSCAN) showed reduced tracer uptake in the putamen bilaterally (Fig. 1C). We started treatment with levodopa at 400mg/24hours, which achieved a limited improvement; the following year, we added pramipexol up to 1.57mg, which achieved no clinically relevant changes. Two years after the initial consultation, the patient presented disabling postural tremor, which appeared when extending the limbs without latency; and irregular intention tremor, of high amplitude and low frequency, when picking up objects. He did not present dysmetria, and physical examination showed right-sided laterocollis. Five years after symptom onset, he began to present instability with falls and ataxic gait, and scored 2/4 in the retropulsion test; laterocollis had also worsened. Cervical dystonia improved with administration of botulinum toxin. Seven years after the initial consultation, the patient reported freezing of gait when beginning to walk and when turning, and scored 4/4 on the retropulsion test. Treatment was started with safinamide, but no improvements were observed. Throughout the progression of his disease, the patient never reported motor fluctuations or dyskinesia, and limb tremor and bradykinesia remained stable. Therefore, our patient presented a parkinsonian syndrome with several atypical characteristics: scarce response to dopaminergic treatment, early onset of highly disabling postural and intention tremor, and progressive laterocollis due to cervical dystonia. Five years after onset, he also began presenting instability, falls, ataxic gait, and freezing of gait.

A) Axial FLAIR MRI sequence, showing extensive right temporal encephalomalacia associated with a craniectomy performed due to tuberculous meningitis during childhood, as well as perivascular spaces in the hippocampus, caudal part of the striatum, and bilateral midbrain. B) Sagittal 3D T2-weighted (CISS) MRI sequence, showing cystic lesions in the fourth ventricle and perivascular spaces in the midbrain. C) SPECT study with ioflupane (I-123) (DaTSCAN), showing reduced tracer uptake in the putamen bilaterally.

While it is not possible to unequivocally rule out a degenerative cause, we believe that some of these manifestations may have been influenced by the presence of the midbrain VRS. Through compressive or ischaemic mechanisms, these spaces can damage such structures as the dentatorubrothalamic tract; this may explain the patient's tremor, which resembled rubral tremor due to the large amplitude and low frequency.12 The cervical dystonia, presenting as laterocollis, may also be explained by structural damage to the midbrain,13 as this is not a common form of presentation of cervical dystonia in atypical parkinsonism.

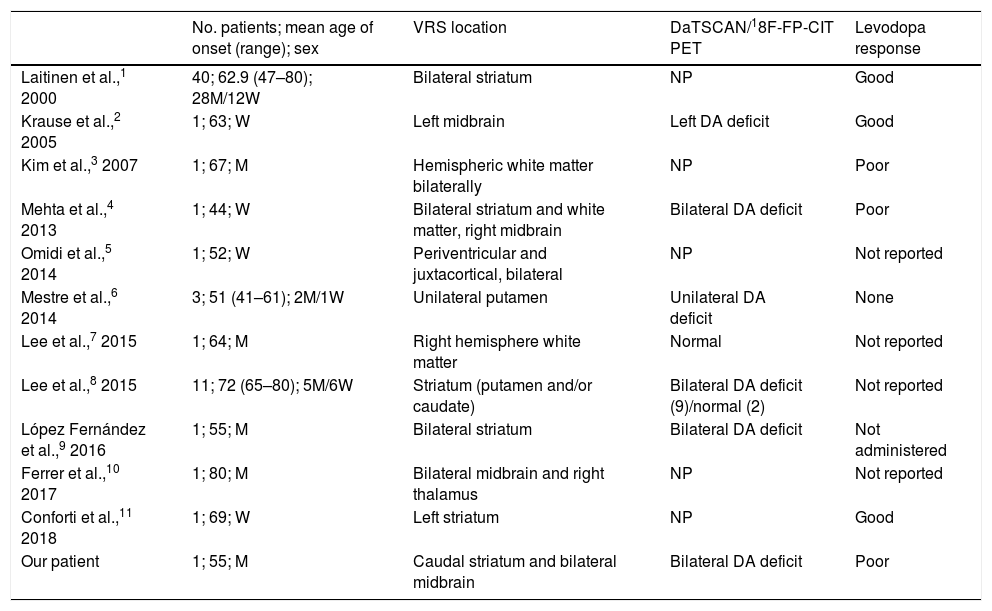

Perivascular spaces or VRS are interstitial fluid – filled spaces that surround blood vessels along their course through the brain parenchyma; they are continuous with the subpial space and do not directly connect with the subarachnoid space. It has been suggested in recent years that they may play a role in the lymphatic drainage of the brain.14 The precise reason that they appear is unknown. One hypothesis suggests that they originate from altered arterial wall permeability due to vasculitis; this may be related to the history of tuberculous meningitis in our patient. VRS are generally not considered to be pathological, although cases have been reported of an association with parkinsonian syndromes; a pathogenic role is probable when they are located in the midbrain or striatum (Table 1). Some patients present clinical manifestations of atypical parkinsonism, as is the case with our patient.8,9

Cases of Virchow-Robin spaces associated with parkinsonian syndromes.

| No. patients; mean age of onset (range); sex | VRS location | DaTSCAN/18F-FP-CIT PET | Levodopa response | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laitinen et al.,1 2000 | 40; 62.9 (47–80); 28M/12W | Bilateral striatum | NP | Good |

| Krause et al.,2 2005 | 1; 63; W | Left midbrain | Left DA deficit | Good |

| Kim et al.,3 2007 | 1; 67; M | Hemispheric white matter bilaterally | NP | Poor |

| Mehta et al.,4 2013 | 1; 44; W | Bilateral striatum and white matter, right midbrain | Bilateral DA deficit | Poor |

| Omidi et al.,5 2014 | 1; 52; W | Periventricular and juxtacortical, bilateral | NP | Not reported |

| Mestre et al.,6 2014 | 3; 51 (41–61); 2M/1W | Unilateral putamen | Unilateral DA deficit | None |

| Lee et al.,7 2015 | 1; 64; M | Right hemisphere white matter | Normal | Not reported |

| Lee et al.,8 2015 | 11; 72 (65–80); 5M/6W | Striatum (putamen and/or caudate) | Bilateral DA deficit (9)/normal (2) | Not reported |

| López Fernández et al.,9 2016 | 1; 55; M | Bilateral striatum | Bilateral DA deficit | Not administered |

| Ferrer et al.,10 2017 | 1; 80; M | Bilateral midbrain and right thalamus | NP | Not reported |

| Conforti et al.,11 2018 | 1; 69; W | Left striatum | NP | Good |

| Our patient | 1; 55; M | Caudal striatum and bilateral midbrain | Bilateral DA deficit | Poor |

DA: dopaminergic; M: men; NP: not performed; VRS: Virchow-Robin spaces; W: women.

In conclusion, while VRS are a common finding in neuroimaging studies, we believe that they may play a pathogenic role when they are large and numerous, and when they involve structures related to the patient's symptoms.

Please cite this article as: Iridoy MO, Clavero P, Cabada T, Erro ME. Espacios de Virchow-Robin mesencefálicos y parkinsonismo: caso clínico y revisión de la literatura. Neurología. 2021;36:171–173.