Antisynthetase syndrome is a rare disease, with varying degrees of lung, muscle, joint, and skin involvement. Due to the introduction of new diagnostic tests, it is possible to detect the disease earlier and to determine the best treatment strategy. However, in our country the availability of these tests is limited. We present the case of a patient with antisynthetase syndrome associated with anti-PL7 antibodies in whom, thanks to the early identification of these antibodies, timely initiation of treatment for the disease was achieved.

El síndrome antisintetasa corresponde a una enfermedad infrecuente, con grados de compromiso variable a nivel pulmonar, muscular, articular y cutáneo. Gracias a la introducción de nuevas pruebas diagnósticas, es posible detectar de forma más temprana la enfermedad y determinar la mejor estrategia de manejo. Sin embargo, en nuestro país la disponibilidad de estas pruebas es limitada. Se presenta el caso de una paciente con síndrome antisintetasa asociado con anticuerpos anti-PL7 en quien, gracias a la rápida identificación de dichos anticuerpos, se logró el inicio oportuno del tratamiento para la enfermedad.

Antisynthetase syndrome (ASS) is an infrequent autoimmune disease, with a heterogeneous clinical presentation that encompasses different degrees of muscle, lung, articular and cutaneous involvement.1 Since its initial description 30 years ago,2 the evidence in this regard has increased. Currently, there are many specific serological markers additional to anti-Jo1 antibodies, that not only allow us to establish the diagnosis, but also to predict the clinical behavior.3 We present the case of a patient who started with interstitial lung disease (ILD), cutaneous manifestations and incipient muscle involvement indicative of inflammatory myopathy (IM) in whom, thanks to the early identification of the anti-PL7 antibody, which is specific for ASS, a timely intervention of the disease was achieved.

Case presentationA 36-year-old woman, born in and coming from Bogotá, evaluated by our service for the first time in January 2021, reported the onset of symptoms in July 2020 with dry, intermittent cough, without other associated respiratory symptoms. In addition, she reported the appearance of erythematous macules and papules on the back of the hands over the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints, associated with non-pruriginous, non-painful erythematous-violaceous macules in the periorbital region and elbows in September 2020. Likewise, she also had a feeling of muscle weakness that resolved after 2weeks. The patient reported alopecia, appearance of intermittent non-painful oral ulcers on the palate, dysphagia for solids, arthralgias with inflammatory characteristics in the hands, carpus, elbows and knees, associated with morning stiffness for 3h and Raynaud phenomenon (RP), all these symptoms with the same time of evolution. In October 2020, she presented exacerbation of the cough, accompanied by dyspnea that progressed from functional class I/IV to III/IV, which led her to require hospital management.

Prior to the assessment, she was hospitalized on 2 occasions, the first in October 2020 due to the presence of the respiratory symptoms described. COVID-19 infection was ruled out and the patient received antibiotic management for a week with a presumptive diagnosis of bacterial pneumonia. On the second opportunity, in December 2020, due to similar symptoms, she received antibiotic treatment for 2weeks and was discharged with a diagnosis of ILD associated with probable dermatomyositis, for which she was being treated with azathioprine 50mg every 12h, prednisolone 20mg/day and supplemental oxygen via nasal cannula at 2l/min 24h a day. As antecedents, the patient presented a COVID-19 infection in June 2020, for which she required outpatient management, and reported a history of left oophorectomy due to ovarian tumor of uncertain characteristics. Her mother has a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The physical examination documented heliotrope erythema, Gottron papules, Gottron sign and mechanic’s hands (Figs. 1 and 2). The presence of RP was also found, with no evidence of synovitis in the evaluation. On auscultation, the presence of rales at both pulmonary bases was observed. No alterations were found in the abdominal or neurological physical examination.

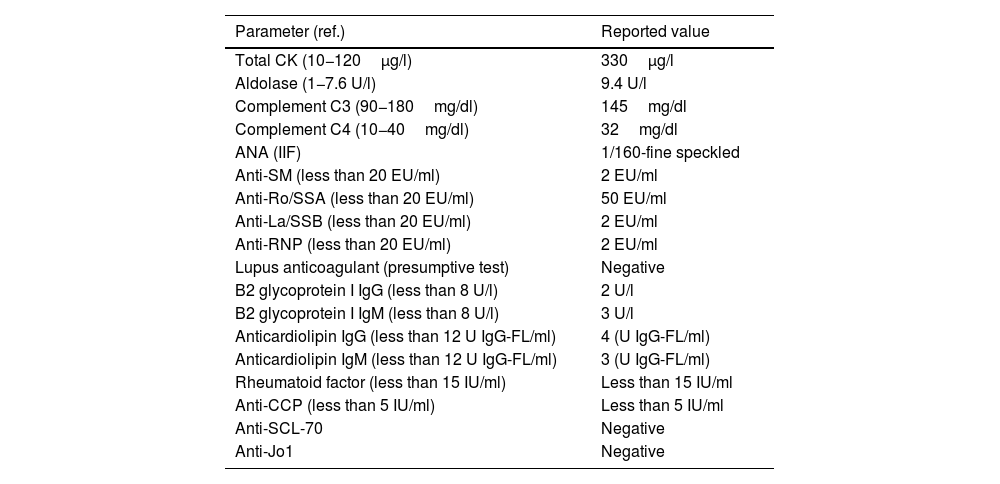

The laboratory tests of December 2020 showed: mild leukocytosis, normal kidney function, urinalysis without alterations, normal lipid profile, normal thyroid function, slight elevation of total creatine kinase and aldolase, as well as elevation of transaminases. The chest X-ray of October 2020 showed ground glass opacities with a peripheral distribution in both lung fields. In December 2020, a chest tomography (HRCT) was performed with findings of ground glass patches of peripheral and random distribution in both lung fields, with involvement of approximately 20% of the lung parenchyma. The immune profile is presented in Table 1. During her hospitalization in December 2020, a transthoracic echocardiogram was performed, with no alterations, while during the 6min walk test, a drop in oxygen saturation (SatO2) during exercise was observed as the only pathological finding. The spirometry with flow-volume curve found a forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1), with moderate to severe decrease, and a normal forced vital capacity (FVC).

Immune profile of the patient during December 2020.

| Parameter (ref.) | Reported value |

|---|---|

| Total CK (10−120μg/l) | 330μg/l |

| Aldolase (1−7.6 U/l) | 9.4 U/l |

| Complement C3 (90−180mg/dl) | 145mg/dl |

| Complement C4 (10−40mg/dl) | 32mg/dl |

| ANA (IIF) | 1/160-fine speckled |

| Anti-SM (less than 20 EU/ml) | 2 EU/ml |

| Anti-Ro/SSA (less than 20 EU/ml) | 50 EU/ml |

| Anti-La/SSB (less than 20 EU/ml) | 2 EU/ml |

| Anti-RNP (less than 20 EU/ml) | 2 EU/ml |

| Lupus anticoagulant (presumptive test) | Negative |

| B2 glycoprotein I IgG (less than 8 U/l) | 2 U/l |

| B2 glycoprotein I IgM (less than 8 U/l) | 3 U/l |

| Anticardiolipin IgG (less than 12 U IgG-FL/ml) | 4 (U IgG-FL/ml) |

| Anticardiolipin IgM (less than 12 U IgG-FL/ml) | 3 (U IgG-FL/ml) |

| Rheumatoid factor (less than 15 IU/ml) | Less than 15 IU/ml |

| Anti-CCP (less than 5 IU/ml) | Less than 5 IU/ml |

| Anti-SCL-70 | Negative |

| Anti-Jo1 | Negative |

ANA: antinuclear antibodies; anti-CCP: anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies; anti-La/SSB: anti-La/SSB antibodies; anti-RNP: anti-U1RNP antibodies; anti-Ro/SSA: anti Ro/SSA antibodies; anti-SCL-70: anti-SCL70 antibodies; anti-SM: anti-Smith antibodies, CK: creatine kinase; IIF: indirect immunofluorescence; IgG: type G immunoglobulin; IgM: type M immunoglobulin.

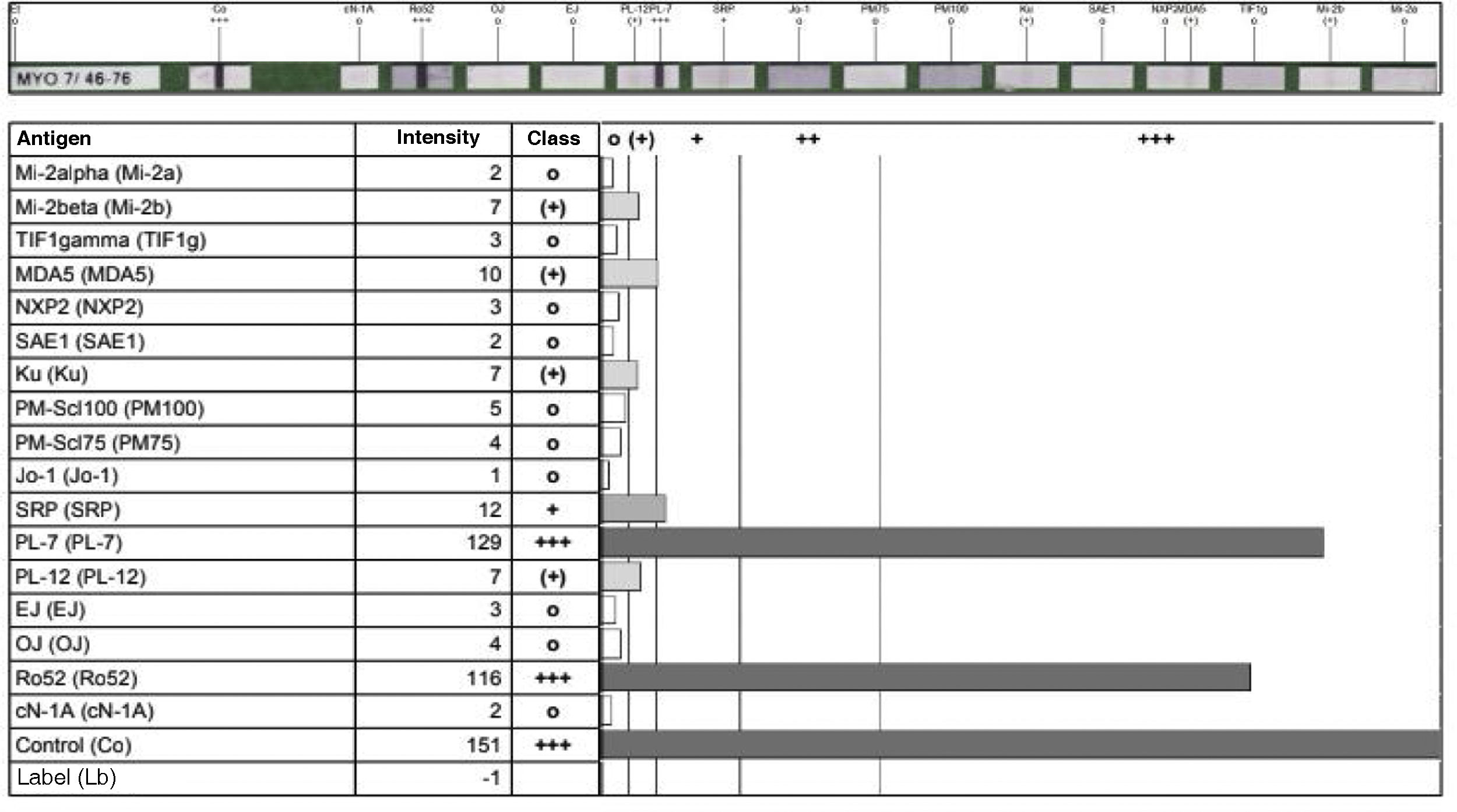

All these findings were interpreted as a probable case of ASS, so the measurement of specific antibodies was performed (Fig. 3), after which the diagnosis of ASS was confirmed. Due to the antibodies found and the rapidly progressive lung involvement, it was considered a disease of poor prognosis, so treatment with cyclophosphamide in monthly boluses of 750mg intravenously was started and azathioprine was discontinued. Treatment with prednisolone 20mg/day was continued.

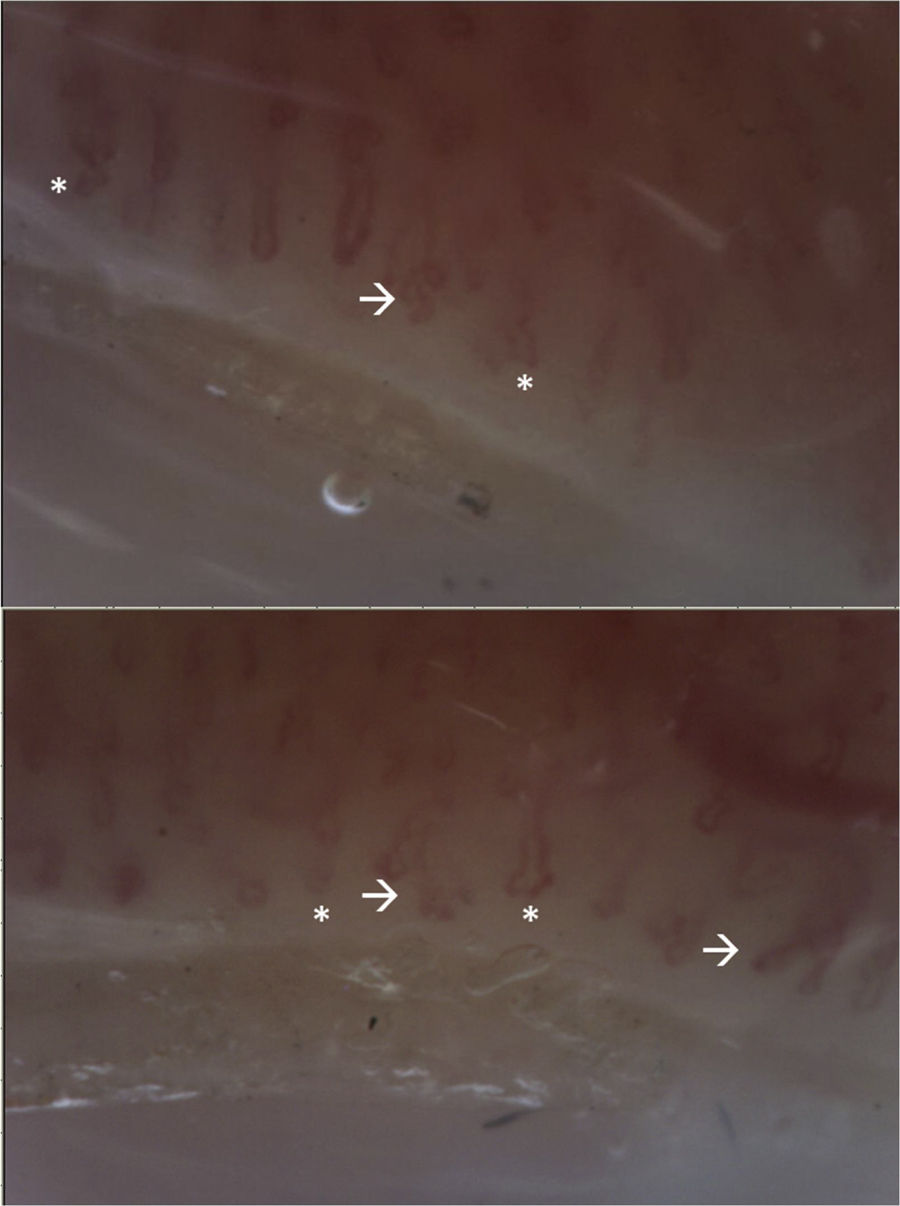

The patient attended a control consultation in March 2021 and received the first dose of cyclophosphamide without complications. Due to the presence of RP, a capillaroscopy was performed with a report of non-scleroderma pattern (Fig. 4). In addition, a lung scintigraphy was performed, which was normal, as well as an electromyography and nerve conduction study of the 4 extremities – without alterations – and a transvaginal ultrasound, which was within normal limits. It was indicated to continue management with cyclophosphamide and prednisolone.

Video-capillaroscopy. Vascular bed with marked papillary edema, linear tortuosities and on its same axis (*), without microhemorrhages or megacapillaries. Branches are evident (arrow). Abnormal pattern, corresponding to non-sclerodermal pattern. The presence of multiple branches suggests the presence of dermatomyositis.

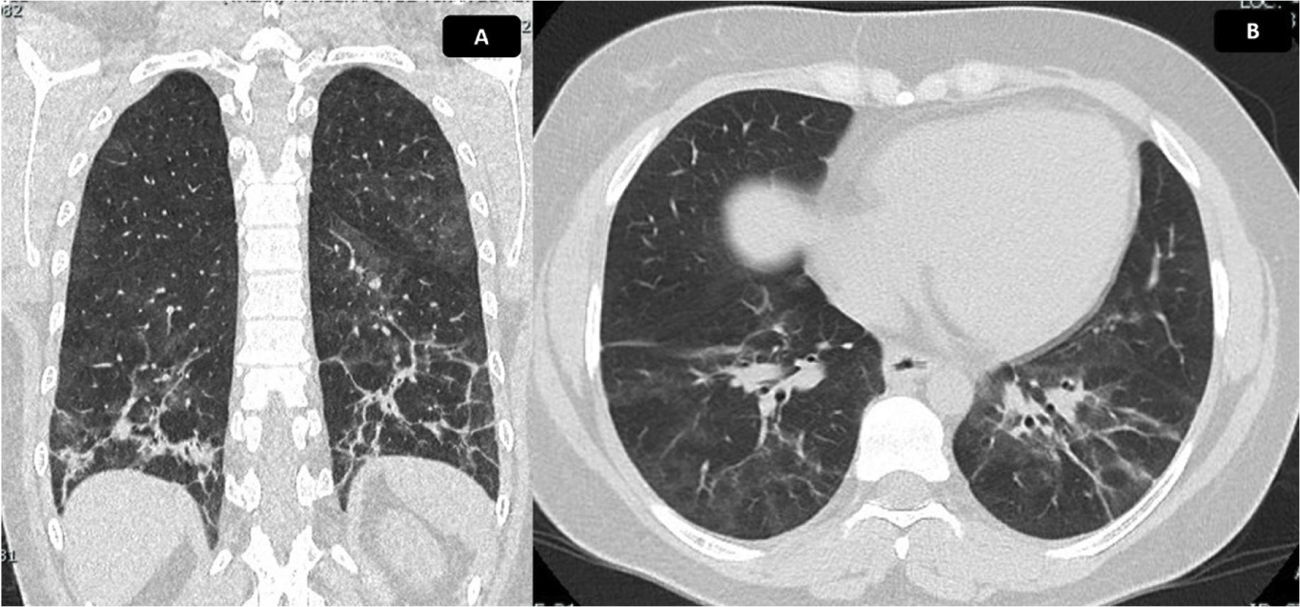

In April 2021, the patient received the second dose of cyclophosphamide without presenting complications. A control of pulmonary function tests (PFT) was performed, which showed a diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide adjusted for altitude moderately decreased, with a value of 60%. The spirometry reported a FVC of 69%, a FEV1 of 68% and a FEV1/FVC ratio of 86. It was indicated to continue the same treatment, with monthly clinical follow-up; however, due to administrative procedures with her insurance company, she attended control until June 2021, without pharmacological treatment since May of that same year. She also reported worsening of cough and dyspnea 20 days before the consultation, associated with fever, myalgia, asthenia and adynamia. A significant drop in SatO2 was documented, in addition to synovitis and RP, and for this reason the patient was hospitalized to rule out an active infectious process. Blood and urine cultures were taken, with negative reports; molecular tests for SARS-CoV-2 were carried out, with negative reports, in addition to negative bacilloscopies and a new control chest tomography (Fig. 5), in which progression of ILD was documented. Symptoms secondary to reactivation of ASS were considered, so prednisolone was restarted at a dose of 20mg/day; the third bolus of cyclophosphamide was administered in-hospital and the patient was discharged with an order for the fourth bolus of cyclophosphamide. After this fourth dose, the evolution was stationary, therefore, control of PFT and HRCT was indicated after completing a treatment scheme of cyclophosphamide for 6months to determine the need to start rituximab.

Chest CT scan with findings of ILD. Chest tomography in coronal (A) and axial (B) sections. Ground glass of peribronchovascular distribution is evident, with greater involvement of posterior segments and lower lobes, where reticulation, parenchymal bands, thickening of bronchial walls and traction bronchiectasis with associated volume loss are identified, due to retraction of fissures. Findings compatible with fibrotic NSIP. Calculated extension of 30%.

ASS corresponds to a rare clinical entity that is currently recognized as a subtype of IM characterized by different degrees of muscle, lung, articular and cutaneous involvement.4 Its pathogenesis is not fully understood, however, the importance of the antibodies directed against tRNA-synthetases (ASab) is increasingly recognized. The interaction of genetic and environmental factors is required for their development. Due to mechanical factors or by the action of local microorganisms, injury to the lung endothelium is generated, which leads to the exposure of autoantigens that in genetically predisposed individuals trigger phenomena of loss of tolerance and production of autoantibodies.5

A prevalence of 1–9/100,000 inhabitants is estimated and may account for up to one third of IM cases, being less prevalent than dermatomyositis and polymyositis, but more frequent than inclusion body myopathy and immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy.6 Thanks to the introduction of new diagnostic techniques and the identification of new ASab, it is probable that these values will change in the coming years.

Different diagnostic criteria have been proposed and, although so far none is universally accepted, all recognize the importance of autoantibodies for the diagnosis of this syndrome.7–9 However, given the heterogeneity of the disease, and the fact that they only include anti-Jo1 antibodies, the need to establish clear classification criteria for ASS has been raised. Currently, at least 8 ASab are recognized, each of them with special characteristics regarding their clinical manifestations, among which anti-PL7 and anti-PL12 stand out, since they confer a worse prognosis at the level of the lungs.10

ASS associated with anti-PL7 (ASS-PL7) is characterized by frequently presenting severe ILD, associated with variable degrees of muscle and skin involvement.3,11,12 Cavagna et al. described the clinical characteristics of a cohort of 95 patients with ASS-PL73 and found that up to 76% presented ILD, being the most common characteristic, as well as the most frequent form of onset of the disease. 49% presented arthritis during the course of the disease and erosions were documented in up to 11% in conventional X-ray. Muscle involvement was present in 80%. Only 30% presented this manifestation at the onset of the disease, however, 61% developed myositis in the course thereof.

With respect to skin involvement, 50% of patients presented RP and the presence of mechanic's hands was documented in 42%. Mortality reached 13% in an average follow-up of 93 months.3 In turn, it has been described that muscle involvement is usually mild and responds adequately to treatment, which is why it can be clinically imperceptible, unlike lung involvement, which does not exclude the diagnosis of ASS-PL7.10,11 Jiang et al. also found that non-specific interstitial pneumonia is the type of ILD found most frequently in this group of patients (72.7% of cases), presenting itself as the main pattern or associated with organizing pneumonia.12

Since its introduction, the identification of anti-PL7 has played an important role among the patients with ASS. Marie et al. compared the clinical profile of patients with ASS-PL7, ASS associated with anti-Jo1 (ASS-Jo1) and anti-PL12 (ASS-PL12)13 and found that patients with ASS-Jo1 presented a higher degree of muscle and joint involvement when compared with ASS-PL7 and ASS-PL12. In turn, patients with ASS-PL7 and ASS-PL12 presented ILD more frequently, with earlier and more severe onset in the course of the disease when compared with ASS-Jo1.13 Due to the impact of lung involvement in patients with ASS, the identification of anti-PL7 and anti-PL12 impacts long-term outcomes and entails a worse prognosis when compared with anti-Jo1.10,13

There is no consensus for the management of ASS and the evidence in this regard derives most of the time from observational studies and the treatment of IMs.14 Early identification of the disease subtype will make it possible to determine the best treatment strategy, based on the combination of different immunosuppressive drugs.15 In relation to ILD secondary to ASS, the first line of treatment corresponds to glucocorticoids associated with immunosuppressive drugs such as azathioprine, mycophenolate, tacrolimus, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide or rituximab.16 There are also reports of the use of immunoglobulin, plasmapheresis and lung transplantation.17,18 It is primordial to identify the severity of the ILD and its degree of progression. In the case of rapidly progressive ILD and acute and subacute forms associated with the presence of poor prognostic factors, there is evidence that suggests that the use of cyclophosphamide in combination with glucocorticoids may improve muscle involvement, in addition to pulmonary function tests, and be well tolerated by patients.19 On the other hand, when chronic progressive ILD occurs, the use of glucocorticoids in combination with other immunosuppressants, such as azathioprine, mycophenolate or cyclosporine, is recommended.20 In the case of refractory ILD, there is evidence of the use of rituximab, tofacitinib or plasmapheresis.20,21

Due to the multiple reports and observational studies of the use of rituximab in ILD associated with connective tissue diseases, the RECITAL study was developed, a randomized clinical trial that compared the use of rituximab with the use of cyclophosphamide in the treatment of ILD associated with connective tissue diseases, including ASS, and sought to define its possible role as a first-line therapy.22 The final results are currently awaited.

In the case of our patient, the clinical course has been similar to that reported in the literature. In addition, thanks to the early identification of anti-PL7 antibodies, the need to initiate immunosuppression with cyclophosphamide was determined, which has allowed to reach a stabilization of the disease. However, taking into account the poor prognostic factors it has, especially the presence of anti-PL7, strict follow-up is required to determine the need to start second-line therapies such as rituximab.

Currently, ASab are the main paraclinical tool to make a timely diagnosis and initiate treatment according to the condition of each patient. The present case illustrates the importance of having these diagnostic tests in our setting, in addition to the need to sensitize pulmonologists, dermatologists and rheumatologists about the possibility of being faced to this disease in cases of IM.

Ethical considerationsAs this is a case report, it does not require an ethics committee, and the patient’s signed authorisation is available.

FundingThis case report did not receive any funding.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest for the preparation of this article.

None.