The purpose of this study was to analyse the predictive power of responsibility on the index of psychological mediators, this on the autonomous motivation, and this on the school climate and the perception of school violence through the Self-Determination Theory. A second objective was to verify the possible differences that may exist according to gender and educational stage. To this end, data were collected by means of self-reported questionnaires in different Secondary and Primary Education centres in Physical Education classes, with a sample of 1007 students from Primary (n = 294), Secondary (n = 601) and Baccalaureate and training cycles (n = 112), with a mean age of M = 13.30 (SD = 2.86). Of the participants, 53.6% were girls (n = 540) and 46.4% boys (n = 467). The data were analysed with IBM SPSS 25.0 and AMOS 23.0 software, using structural equation analysis. The results verified the predictive ability of accountability on the index of psychological mediators, autonomous motivation and on school climate and perception of school violence. The analysis of factorial invariance of the model confirmed its robustness to gender, but not to educational stage. According to educational stage, the analysis of variance showed significant differences between Primary School and Secondary School and Baccalaureate/Training, with younger students showing higher values for all variables except violence. It is concluded that responsibility has a relevant role in the educational environment, due to its predictive power on the school climate and school violence, as well as on the satisfaction of basic psychological needs and autonomous motivation, following the Self-Determination Theory. At the same time, students in higher educational stages presented lower values of responsibility, making it necessary to work on it in the classroom. It is recommended that future research should investigate, on the one hand, interventions where the central core is the promotion of responsibility, in addition to conducting longitudinal analyses with samples of students in different contexts, checking whether the model of this study is corroborated and allows creating a line of work for the improvement of school climate and the reduction of the perception of violence.

El propósito del presente estudio es analizar el poder predictivo de la responsabilidad sobre el índice de mediadores psicológicos, de este sobre la motivación autónoma y esta sobre el clima escolar y la percepción de violencia escolar a través de la Teoría de la Autodeterminación. Un segundo objetivo ha sido comprobar las posibles diferencias que puedan existir en función del sexo y la etapa educativa. Para ello, se han recogido datos mediante cuestionarios auto reportados en diferentes centros de Educación Secundaria y Educación Primaria en las clases de Educación Física, para lo que se ha contado con una muestra de 1007 estudiantes de Primaria (n = 294), Secundaria (n = 601) y Bachillerato y ciclos formativos (n = 112), con una edad media de M = 13.30. (DT = 2.86). De los participantes, un 53.6% han sido chicas (n = 540) y un 46.4% chicos (n = 467). Se han analizado los datos con el software IBM SPSS 25.0 y AMOS 23.0, mediante un análisis de ecuaciones estructurales. Los resultados verifican la capacidad de predicción de la responsabilidad sobre el índice de mediadores psicológicos, la motivación autónoma y sobre el clima y la percepción de la violencia escolar. El análisis de la invarianza factorial del modelo ha confirmado su robustez en función del sexo, pero no de la etapa educativa. Según la etapa educativa, el análisis de la varianza arroja diferencias significativas en Primaria respecto a Secundaria y Bachillerato/Ciclos Formativos, mostrando los estudiantes de menor edad valores más altos en todas las variables excepto en la violencia. Se concluye que la responsabilidad posee un papel relevante en el entorno educativo por su poder de predicción sobre el clima del centro y la violencia escolar, además de sobre la satisfacción de las necesidades psicológicas básicas y de la motivación autónoma, siguiendo la Teoría de la Autodeterminación. A su vez, los estudiantes de etapas educativas superiores presentan valores más reducidos de responsabilidad, haciéndose necesario su trabajo en las aulas. Se recomienda que futuras investigaciones indaguen, por un lado, en intervenciones donde el núcleo central sea el fomento de la responsabilidad, además de realizar análisis longitudinales con muestras de estudiantes en diversos contextos, comprobando si el modelo del presente estudio se corrobora y permite crear una línea de trabajo para la mejora del clima escolar y la reducción de la percepción de violencia.

The ability of students to regulate their behaviours proactively and effectively is an area of great interest in the educational context (Zimmerman & Schunk, 2011). Moreover, it is in the late primary and early secondary school stages that a major shift from childhood to adulthood occurs, increasing the need to acquire coping skills for adult life (Lang et al., 2017). It is therefore essential to promote responsibility as a variable that enables the development of educational values such as respect and effort, both in and out of school (Escartí et al., 2018). Nowadays, a variety of situations arising from different forms of violence are generated in the classroom, and it is considered a serious problem at international level (Salimi et al., 2021; Zuñiga et al., 2019). Therefore, it is necessary to promote an appropriate school climate in schools in order to have a positive influence on student behaviour (Rizzotto & França, 2022).

The promotion of responsibility is considered essential for people's personal development (Gordon et al., 2016) and has a great capacity for the promotion of values that enable their social growth (Melero et al., 2019). There are several studies that relate responsibility to variables such as motivation (Merino-Barrero, Valero-Valenzuela & Belando-Pedreño, 2019), violence (Lamoneda-Prieto, 2019) or school climate (Manzano-Sánchez, 2021). In this sense, it is worth highlighting the need to promote responsibility in schools, with the Personal and Social Responsibility Model (TPSR), which is widely used in the context of Physical Education and sport, being an essential tool. Donald Hellison (1985; 2011) has created this model and its origins date back to Boston (United States), as a programme for the promotion of values in young people in social exclusion through sport, seeking transfer to real life (Hellison & Wright, 2003).

TPSR has now been consolidated as a basic pedagogical model for this subject (Pérez-Pueyo et al., 2021) that has shown how the promotion of responsibility can improve numerous psycho-social aspects, such as autonomous motivation or the satisfaction of the needs for autonomy, competence and social relations or school climate (Manzano-Sánchez & Valero-Valenzuela, 2019). In this sense, the systematic reviews carried out with interventions that have used the TPSR stand out, specifically that of Shen et al. (2022) with more than 40 studies in the context of sport or out-of-school physical activity, as well as that of Pozo et al. (2018) with more than 20 studies in Physical Education. There are also other studies in the field of education that have proven its viability at any educational stage since 2019 (Manzano-Sánchez & Valero-Valenzuela, 2019; Manzano-Sánchez et al. 2020), including other educational levels such as Early Childhood Education (Pavão et al., 2019) or contexts of social exclusion (Martins et al., 2022). It is also highlighted how the development of responsibility with this model also shows relatedness between the basic psychological needs of autonomy, competence, social relatedness and motivation (Hortigüela-Alcalá, Fernández-Río, Pérez-Pueyo et al., 2019).

In this sense, motivation is considered a fundamental element in teaching (Morris & Usher, 2011). Among the theories that analyse it, one of the most widespread is the Self-Determination Theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 1985, 1988, Deci et al., 2013; Ryan & Deci, 2000). This theory offers a theoretical framework that allows us to understand motivation from a scientific perspective that distinguishes a series of levels from the most intrinsic or self-determined motivation (autonomous motivation), through extrinsic motivation (controlled motivation) and ending with demotivation. The most self-determined motivation is a way of leading individuals to become more interested in activities and generate new actions (Unrau & Schlackman, 2006), and is therefore the one that produces the greatest adherence, allowing new behaviours to be generated and others to be maintained.

In turn, Deci and Ryan (2012) differentiate within SDT the so-called basic psychological needs, which act as mediators to generate a more self-determined motivation. Specifically, the needs for autonomy (freedom of choice in one's own behaviour), perceived competence (feeling effective and able to master one's environment) and relatedness (ability to feel connected to other people). Thus, there is well-known research that specifies the relatedness between basic psychological needs and more autonomous motivation, in which it is shown that greater satisfaction of needs improves more autonomous motivation (Leyton et al., 2020). Following the SDT, there are numerous existing research studies in the field of education, with the systematic review by Vasconcellos et al. (2020) being noteworthy, with more than 250 articles that meet the specified inclusion criteria, in which the broad scope of research in this field is observed. Moreover, this theory has traditionally worked in Physical Education or sport activities, but has recently been extended to other areas and subjects such as English (Pae, 2008), mathematics (León et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2022) or in the general context of education (Stover et al., 2014), thus reflecting its multidisciplinary scope. It is therefore not surprising that research has analysed its relatedness with variables such as accountability (Manzano-Sánchez et al., 2021), school climate (Verner-Filion et al., 2023) or perception of violence (Assor et al., 2018).

A next step to SDT has been the model devised by Vallerand (1997, 2007), called the “Hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation”, which has demonstrated a broad relatedness with SDT. This model reflects the existence of social antecedents including responsibility (Manzano-Sánchez, 2022; Merino-Barrero et al., 2017; Méndez-Giménez et al., 2012; Moreno-Murcia et al., 2013) which, following this theory, can enhance the satisfaction of the three basic psychological needs, which allows autonomous motivation to be enhanced (Valero-Valenzuela et al., 2021). In turn, this ultimately leads to more adaptive behavioural, cognitive and affective outcomes (Ryan & Deci, 2017), such as school climate (Manzano-Sánchez et al., 2020) or perceived violence (Valero-Valenzuela, Manzano-Sánchez et al., 2021).

Based specifically on the present study, only two studies have been found that, following Vallerand's sequence, have predicted certain behaviours. Specifically, from responsibility there is a prediction with friendship goals (Menéndez & Fernández-Río, 2017) and with sportsmanship, intention to be physically active and healthy lifestyle (Merino-Barrero, Valero-Valenzuela, Belando-Pedreño & Fernández-Río, 2019). Similarly, Manzano-Sánchez (2022) has shown how resilience can be predicted from the promotion of responsibility, taking into account Vallerand's sequence, as has been shown by the research of Valero-Valenzuela et al. (2021) in reference to perceived violence. In turn, school climate has acted, together with responsibility, as a trigger to reduce the perception of violence (Manzano-Sánchez et al., 2021), making it interesting to know whether responsibility, on its own, can predict this consequence.

The last step in Vallerand's sequence is formed by the consequences of this theory. In the first place, violence should be highlighted. Thus, in the school context, Álvarez et al. (2010), detail that violence is intentional behaviour that causes harm or damage, which has been inversely related to school climate (Carbonero et al., 2010), basic psychological needs (Carrasco & Trianes, 2010) and directly to less self-determined motivation (Valero-Valenzuela et al., 2021). It is not surprising, therefore, that in recent years there has been a proliferation of studies that have carried out interventions aimed at reducing violence in the classroom (Alférez et al., 2022; Navarro-Pérez et al., 2020). Among these, it is worth highlighting the study by Assor et al. (2018), which shows very positive results in the reduction of perceived violence, which is also based on the use of strategies related to SDT. Finally, the review by Mena et al. (2022) shows how school violence is a matter of high scientific interest, finding that while not all interventions are effective, about 90% (12 of the 14 studies analysed) are adequate for its reduction.

Secondly, following Vallerand's sequence and taking into account the fundamental role that school climate plays in schools to minimise social problems (Reaves et al., 2018), reduce aggression (Amaral et al., 2019) or reduce school violence (Varela et al., 2019), it is particularly relevant to study this second variable. School climate can be defined as the set of socio-ecological influences of individuals, teachers, peers, school-level organisations, families and neighbourhoods that can be targets for prevention (Mischel & Kitsantas, 2019), being a fundamental aspect for the development of teaching (López & Oriol, 2016). Finally, it is worth highlighting the study by Da Cunha et al. (2021), which indicates the relatedness between social responsibility and a positive school climate in order to reduce aggressive behaviour. Thus, it is advisable to promote social climates in schools that encourage support and an adequate structure to reduce the levels of aggression and victimisation through the promotion of responsibility (Amaral et al., 2019).

Based on SDT and the research described above, teachers tend to highlight the development of accountability as fundamental and how it can lead to an improvement in student behaviour and school climate (Manzano-Sánchez et al., 2020). In this sense, no research has been found in which accountability alone predicts school climate and perceived violence. There is only research that analyses the violence variable, either separately (Valero-Valenzuela et al., 2021), or using school climate as a trigger together with responsibility (Manzano-Sánchez et al., 2021).

Hence, it is necessary to analyse the socio-demographic variables that may influence the relatedness indicated. Some of the studies cited in the field of education indicate that variables such as responsibility, motivation or basic psychological needs vary according to the age and gender of their students. For example, Kipp and Bolter (2020) found that the only variable that reported significant differences in responsibility was the perception of autonomy, with younger children (8-10 years) having higher values than those found in early adolescence (sixth or seventh grade or 11-13 years). These findings are similar to those of Manzano-Sánchez (2021), who conclude that both levels of responsibility and more self-determined motivation and school climate are higher in primary school children, while violence is lower in secondary school children. Similarly, gender can influence the results in terms of the psychological profile of children and adolescents. In this line, Manzano-Sánchez et al. (2019) have shown how when implementing methodologies in Physical Education, the results can be different, in this case, with greater improvements in girls than in boys.

Therefore, the first objective of this study was to analyse the predictive power of responsibility on school climate and perceived violence, using satisfaction of basic psychological needs and autonomous motivation as mediators. As a second objective, we sought to find possible differences between psychosocial variables according to gender and educational stage of the students. It is hypothesised that: (1) responsibility has a positive effect on the index of psychological mediators, predicting positively autonomous motivation and school climate, and negatively school violence; (2) the average levels of the different psychosocial variables are similar according to gender but differ according to educational stage, showing worse values for responsibility, satisfaction of basic psychological needs, autonomous motivation and violence for older ages.

MethodParticipantsA total of 1,007 students selected by accessibility from four schools in the Region of Murcia took part. The socio-economic characteristics of the families were similar, with a medium-low profile. Data collection was carried out during the 2018-2019, 2019-2020 and 2020-2021 academic years, specifically in the months of September and October, coinciding with the start of the school year. The student body of the study corresponds to the Primary Education stage (n = 294), Compulsory Secondary Education (n = 601) and Baccalaureate and Training Cycles (TC) in administration and finance (n = 112). Of the total sample, 540 (53.6%) were male and 467 (46.4%) female, aged between 9 and 23 years, with an average age of M = 13.30 (SD = 2.86).

InstrumentsA multiple-choice questionnaire with a Likert-type scale was used, comprising a series of socio-demographic variables (date of birth, educational stage and gender) and four questionnaires for the analysis of the variables under study.

Questionnaire for the analysis of levels of personal and social responsibility (PSRQ; Li et al., 2008; Spanish version by Escartí et al., 2011). It seeks to measure levels of personal responsibility (e.g. “I want to improve”) and social responsibility (e.g. “I respect others”). It starts with the following premise: “It is normal to behave sometimes well and sometimes badly, we are interested in knowing how you normally behave during class”, consisting of a Likert-type scale with a minimum value of one and a maximum of five and a total of 14 items. In this research, the reliability values for each dimension were α = .87 (social responsibility) and α = .76 (personal responsibility). Confirmatory factor analysis was performed for a two-factor hierarchical model, obtaining acceptable fit indices: χ2(67, N = 1,007) = 190.40, p < .01, χ2/df = 2.84, CFI = .98, IFI = .98, TLI = .98, RMSEA = .04, RMSR = .03.

Questionnaire for the Analysis of Basic Psychological Needs (PNSE; by Vlachopoulos & Michailidou, 2006; Spanish version by Moreno-Murcia et al., 2008). To measure the basic psychological needs of autonomy (e.g. “I believe I can make decisions regarding my activities”), perceived competence (e.g. “I believe I can complete exercises that are a personal challenge”) and social relatedness (e.g. “I believe I get along well with those I relate to when we exercise together”). It consists of a Likert-type scale with a minimum value of one to five and a total of 12 items. Reliability values were α = .74 (autonomy), α = .76 (competence) and α = .76 (relatedness). The confirmatory factor analysis yielded the following values: χ2(47, N = 1,007) = 160.62, p < .01, χ2/df = 3.42, CFI = .97, IFI = .97, TLI = .96, RMSEA = .05, RMSR = .04.

Échelle de Motivation en Éducation (EME; Vallerand, 1997, 2007; Spanish version Nuñez et al., 2005). To measure student motivation. The 16 items that make up autonomous motivation are used in four scales, namely intrinsic motivation towards knowledge (e.g. “for the pleasure of knowing more about the subjects I am attracted to”), towards achievement (e.g. “for the satisfaction I feel when I excel in my studies”), towards stimulating experiences (e.g. ““because of the pleasure I experience when I feel completely absorbed”), and identified regulation (e.g. “because it will help me to make a better choice of career direction”), always under the premise of” Why do you go to school or high school? For the analysis of this questionnaire, the variable called Autonomous Motivation was generated (from the average obtained in the four scales). The reliability values of the four scales separately were α = .82 (intrinsic motivation towards knowledge), α = .83 (intrinsic motivation towards achievement), α = .77 (intrinsic motivation towards stimulating experiences), α = .68 (identified regulation). The measurement model yielded the following fit indices: χ2(95, N = 1,007) = 365.18, p < .01, χ2/df = 3.84, CFI = .97, IFI = .97, TLI = .96, RMSEA = .05, RMSR = .03.

School Climate Scale (CECSCE; Trianes et al., 2006): This scale has been used to analyse the climate perceived by students in relation to teachers and in relation to the school. The questionnaire is composed of two subscales called school climate (e.g. “students really want to learn”), composed of eight items, and teacher climate (e.g. “teachers at this school are nice to students”), composed of six items with a five-point Likert-type scale, from one to five, with a total of 14 items. Both scales were combined in the so-called climate. Reliability values were α = .86 (school climate), α = .77 (teacher climate). The confirmatory factor analysis yielded the following fit indices: χ2(74, N = 1,007) = 242.65, p < .01, χ2/df = 3.28, CFI = .97, IFI = .97, TLI = .96, RMSEA = .05, RMSR = .03.

Cuestionario de Violencia Escolar (CUVE; Álvarez et al., 2006, 2013). It is divided into a version for secondary school with eight subscales and one for primary school with seven subscales. In the case of secondary school, the subscale of violence through information and communication technologies is included (which has not been used to homogenise the responses of both groups). The scale has a value between one and six, with a total of 34 items. The subscales are teacher violence towards students with ten items (e.g. “teachers do not listen to their students”), indirect physical violence by students with five items (e.g. “students steal things from teachers”), direct physical violence between students with five items (e.g. “students get into fights within the school premises”), verbal violence by students towards teachers with three items (e.g. “students make annoying remarks to their classmates”), verbal violence by students towards classmates with three items (e.g. “students make annoying remarks to their classmates”, “students use nicknames to their classmates”), social exclusion with three items (e.g. “certain students are discriminated against by their classmates”) and classroom disruption with three items (e.g. “students make it difficult for teachers to explain things by talking in class”). The reliability values for each of the scale constructs are α = .80 (teacher violence towards students), α = .72 (indirect physical violence by students), α = .80 (direct physical violence between students), α = .75 (verbal violence by students towards peers), α = .78 (verbal violence by students towards teachers), α = .80 (social exclusion), α = .76 (disruption in the classroom). To improve the fit indices of the model, items 1, 2, 20, 40 and 43 belonging to the subscales of verbal violence from students to peers, violence from teachers to students, verbal violence from students to teachers, direct physical violence between students and disruption, respectively, were eliminated. The measurement model yielded acceptable values: χ2(345, N = 1,007) = 1658.77, p < .01, χ2/df = 4.81, CFI = .92, IFI = .92, TLI = .90, RMSEA = .06, RMSR = .04.

ProcedureA research design approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Murcia (1685/2017) was carried out. The directors of the schools were contacted to inform them about the project and, once they had given their approval, a series of information sheets were administered to the schools, as well as to the participants, to confirm their willingness to take part in the study and to obtain the informed consent of the parents or guardians. In order to pass the questionnaire, a power point presentation was prepared together with an explanation for the pupils, in addition to advising them on any possible doubts during the test, which lasted between 15 and 25 minutes.

Data analysisAverage, standard deviations, skewness and kurtosis values and reliability were analysed for all the variables under study. It was considered acceptable that the reliability coefficients of the scale were above .70 (Nunnally, 1978). A two-step maximum likelihood (ML) approach suggested by Kline (2016) was used. For cut-off points, the following were considered acceptable: CFI and TLI ≥ .90, and RMSEA and RMSR ≤ .80, following several recommendations (Marsh et al., 1994; Hair et al., 2014). Finally, measurement invariance has been reviewed, evaluating configural, metric, scalar and strict invariance (Byrne, 2016) taking as a criterion the variation of CFI (ΔCFI < 0.01; Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). Finally, to determine the differences in the average of the different variables regarding to gender and educational stage, a MANOVA was used. Box's test, Bartlett's test and Levene's test were carried out to test the initial hypotheses and whether the results can be considered conclusive. The MANOVA was carried out to analyse all the dependent variables together. Differences between gender and educational stage were analysed using a one-way multiple ANOVA. All analyses were carried out with the statistical package SPSS 25.0 and Amos 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

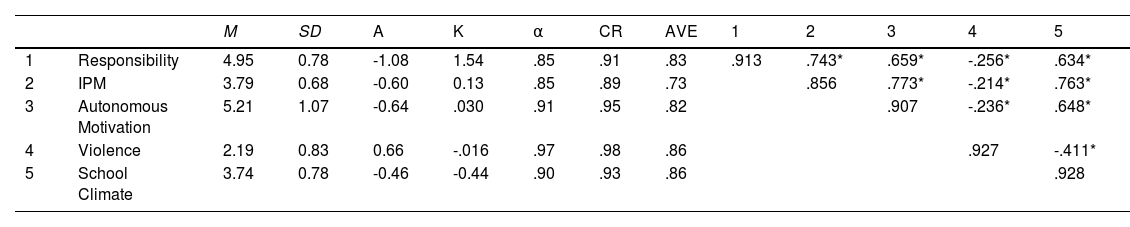

ResultsReliability of scalesIn Table 1, the first columns show the values of the descriptive statistics, skewness and kurtosis, as well as the Cronbach's alpha value. All variables show an acceptable value above .70.

Descriptive analysis of the sample, correlations, reliability and validity

| M | SD | A | K | α | CR | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Responsibility | 4.95 | 0.78 | -1.08 | 1.54 | .85 | .91 | .83 | .913 | .743* | .659* | -.256* | .634* |

| 2 | IPM | 3.79 | 0.68 | -0.60 | 0.13 | .85 | .89 | .73 | .856 | .773* | -.214* | .763* | |

| 3 | Autonomous Motivation | 5.21 | 1.07 | -0.64 | .030 | .91 | .95 | .82 | .907 | -.236* | .648* | ||

| 4 | Violence | 2.19 | 0.83 | 0.66 | -.016 | .97 | .98 | .86 | .927 | -.411* | |||

| 5 | School Climate | 3.74 | 0.78 | -0.46 | -0.44 | .90 | .93 | .86 | .928 |

Note. IPM = index of psychological mediators; M = mean; SD = Standard Deviation; A = Asymmetry; K = Kurtosis. CR = Composite reliability; AVE = Average variance extracted. *p < .001. The diagonal of the correlation matrix is the square root of the AVE.

In addition, Table 1 shows the composite reliability (CR), the reliability of the constructs or latent variables, which must have values equal to or greater than .7. For the study of convergent validity, the average variance extracted (AVE) has been included, which must be greater than .5. As for discriminant validity, the value of the squared correlations of the different variables was compared with the square root of the AVE (Table 1), showing adequate values for all variables.

In order to check the multivariate normality of the factors, we followed Bollen (1989) who states that such normality exists if the Mardia coefficient is less than p (p + 2), where p is the number of variables observed. Taking into account that in this study there are 75 observed variables and the Mardia coefficient provided by the AMOS program is equal to 186.92, the existence of multivariate normality can be affirmed. In addition, the assumption of multicollinearity has been fulfilled as the bivariate correlations between the variables are lower than .85.

Different absolute and relative fit indices were calculated. The indices obtained were: χ2(215, N = 1,007) = 6303.7, p < .01, χ2/df = 2.39, CFI = .90, IFI = .91, TLI = .90, RMSEA = .04, RMSR = .05. The standardised regression weights of the items ranged from .55 to .98, being statistically significant, with a satisfactory error variance (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

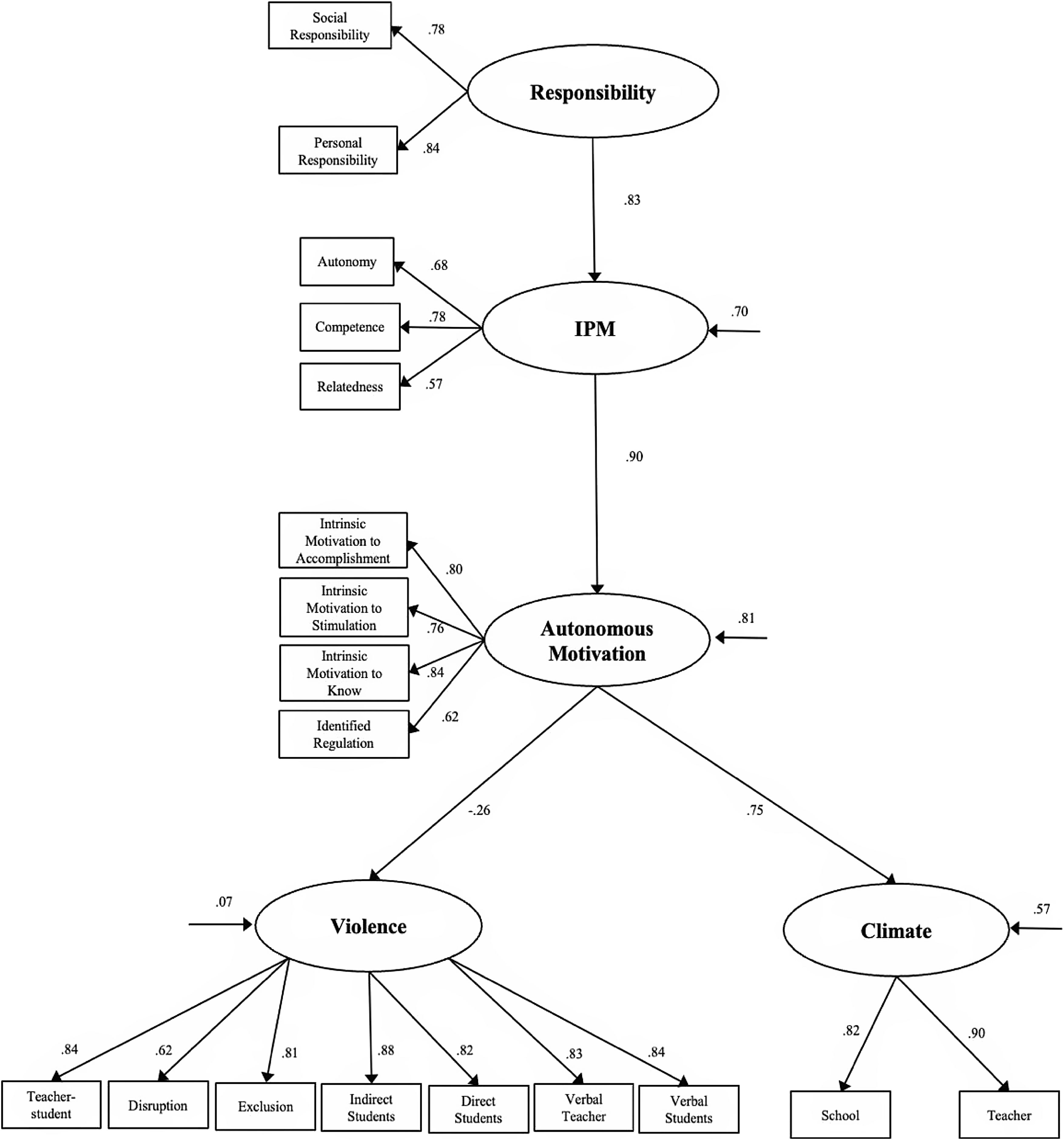

Predictive power of reliabilityThis analysis responds to the first hypothesis of the study. The model was recursive and identifiable. The Mardia coefficient (43.69) was used, with multivariate normality, since the resulting coefficient according to Bollen (1989) is less than p (p + 2), where p is the number of observed variables. The maximum likelihood estimation method was used in the analysis. The goodness-of-fit test of the model has shown adequate fit values (Hu & Bentler, 1999), conforming to the established parameters: χ2(118, N = 1,007) = 905.1, p < .01, χ2/df = 7.67, CFI = .93, IFI = .93, TLI = .91, RMSEA = .08, RMSR = .07. All relatedness were significant, with regression weights ranging between .75 and .90, except for autonomous motivation and violence with -.26 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 also shows the variance explained by each of the variables, with responsibility accounting for 70% of the variance predicting IPM. Thus, IPM explains 81% of the variance of the autonomous motivation variable. Finally, autonomous motivation explains 57% of the variance of climate and 7% of violence.

Direct effectsIn terms of direct effects, responsibility has a positive effect on the psychological mediators index (beta = .83). In turn, the psychological mediators index positively and significantly predicts autonomous motivation (beta = .90). Finally, autonomous motivation has a statistically significant and negative effect on violence (beta = -.26) and a positive effect on school climate (beta = .75).

Indirect effectsThe mediated effects or standardized indirect effects have revealed that responsibility has had a positive effect on autonomous motivation (beta = .75), on climate (beta = .56) and a negative effect on violence (beta = -.19). ). For its part, the IPM has had positive effects on the school climate (beta = .68) and negative effects on violence (beta = -.23).

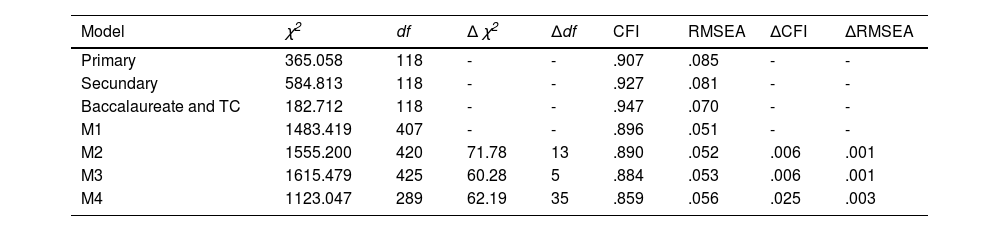

Factorial invariance according to sex and educational stageThis analysis responds to the second hypothesis of the study. Because the structural model presented a good fit, a multigroup confirmatory factor analysis was used to verify its factorial invariance depending on sex and educational stage. Firstly, the configural model (M1) wes established and from this a series of nested models (M2, M3 and M4) were tested. The fit indices have all been favorable, complying with the strict invariance criterion.

In the case of the educational stage (Table 2), the strict variance (M4), referring to the statistical equality of the residuals, the variation of the goodness values of the model has were not been found within the margins necessary for its compliance, with an increase in the CFI > .01, specifically .025, so the most restrictive model has been was rejected.

Measurement invariance of the model depending on the educational stage

| Model | χ2 | df | Δ χ2 | Δdf | CFI | RMSEA | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | 365.058 | 118 | - | - | .907 | .085 | - | - |

| Secundary | 584.813 | 118 | - | - | .927 | .081 | - | - |

| Baccalaureate and TC | 182.712 | 118 | - | - | .947 | .070 | - | - |

| M1 | 1483.419 | 407 | - | - | .896 | .051 | - | - |

| M2 | 1555.200 | 420 | 71.78 | 13 | .890 | .052 | .006 | .001 |

| M3 | 1615.479 | 425 | 60.28 | 5 | .884 | .053 | .006 | .001 |

| M4 | 1123.047 | 289 | 62.19 | 35 | .859 | .056 | .025 | .003 |

Note. M1 = Configural, M2 = Metric, M3 = Scalar, M4 = Strict.

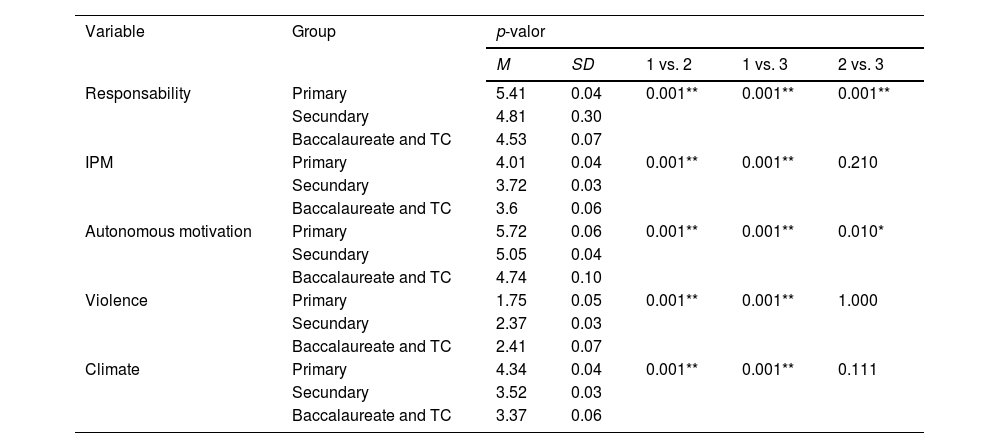

The results obtained from the multivariate analysis show that at the level of educational stage, significant differences were found for responsibility (F = 89.569, p < .001), IMP (F = 25.319, p < .001), autonomous motivation (F = 55.245, p < .001), violence (F = 64.957, p < .001) and climate (F = 164.623, p < .001).

With the aim of comparing the dependent variables depending on the educational stage, the differences between Primary, Secondary and Baccalaureate-Training Cycles were analysed. The estimated average and standard errors for the participants based on the measured variables are presented in Table 3, differentiating by age group and including the p-value obtained by comparing the estimated average (using the Bonferroni correction).

Multivariate analysis based on educational stage (MANOVA)

| Variable | Group | p-valor | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | 1 vs. 2 | 1 vs. 3 | 2 vs. 3 | ||

| Responsability | Primary | 5.41 | 0.04 | 0.001** | 0.001** | 0.001** |

| Secundary | 4.81 | 0.30 | ||||

| Baccalaureate and TC | 4.53 | 0.07 | ||||

| IPM | Primary | 4.01 | 0.04 | 0.001** | 0.001** | 0.210 |

| Secundary | 3.72 | 0.03 | ||||

| Baccalaureate and TC | 3.6 | 0.06 | ||||

| Autonomous motivation | Primary | 5.72 | 0.06 | 0.001** | 0.001** | 0.010* |

| Secundary | 5.05 | 0.04 | ||||

| Baccalaureate and TC | 4.74 | 0.10 | ||||

| Violence | Primary | 1.75 | 0.05 | 0.001** | 0.001** | 1.000 |

| Secundary | 2.37 | 0.03 | ||||

| Baccalaureate and TC | 2.41 | 0.07 | ||||

| Climate | Primary | 4.34 | 0.04 | 0.001** | 0.001** | 0.111 |

| Secundary | 3.52 | 0.03 | ||||

| Baccalaureate and TC | 3.37 | 0.06 | ||||

Note. *p < .05; ** p < .01; M = Media; SD = Standard Deviation; IPM: index of psychological mediators; VT: Vocatonal training; 1: Primary; 2: Secundary; 3: Baccalaureate and Training Cicles.

Most of the variables differ from one educational stage to another, except for the IPM (p = .210), violence (p = 1.000) and climate (p = .111) for the Secondary and Baccalaureate-Training Cycles stages. The rest of the variables present significant differences for the different educational stages.

DiscussionThe first objective of the present study was to analyse the predictive power of responsibility on the school climate and perceived violence through autonomous motivation and the satisfaction of basic psychological needs. Based on the results obtained, it has been proven how the increase in responsibility in students is positively related to the satisfaction of basic psychological needs and autonomous motivation and this, in turn, predicts a better school climate and less perceived violence. This result is of the utmost importance, since it suggests that Physical Education teachers structure their methodology through tasks that encourage student commitment, thus being able to self-regulate their practice and demonstrate what they have learned in each of the applied contents. This fact, associated with their perceived competence, both individually and as a group, results in an improvement in group socialization and less violence, as indicated by the results of the study. Therefore, the first hypothesis proposed is confirmed, since responsibility has a positive effect on the index of psychological mediators, positively predicting autonomous motivation, school climate and negatively predicting school violence. From here a series of implications are drawn for teachers, such as: (1) proposing activities based on the student's perceived competence; (2) develop learning situations that allow students to make decisions about the tasks to be carried out; (3) delimit evaluable productions in each of the learning situations in which the student, individually and in a group, has to demonstrate what they have learned; and, (4) promote student responsibility in daily practice through group work and reflection.

In this sense, research such as that of Romi et al. (2009) attach great importance to promoting responsibility among students, demonstrating how this affects greater involvement in the tasks required. As a consequence, this involvement results in more lasting, transferable and meaningful learning, as long as self-assessment and metacognition processes are favored (Braund & Deluca, 2018). To do this, it is essential to guarantee the subjective value that the student gives to the task, adjusting this perception with that of the teacher himself. In this way, the chances of the student showing greater autonomy towards performance and emotional well-being are increased (Collie, 2021). In this sense, research such as that of Van Aart et al. (2017) have demonstrated, in students between 9 and 12 years old, the positive influence that responsibility has on basic psychological needs, especially influencing autonomous motivation for Physical Education. Considering this effect in the specific area of motivation, it is essential to focus on the relationship with between teachers and classmates, the latter being a determining factor in the generation of autonomous motivation (De Bruijn et al., 2022).

Regarding the school climate, certain research has analysed the direct relationship that exists between a positive classroom climate, based on the interpersonal relationships established among the students, and the responsibility of each of its members (Barksdale et al., 2019). This responsibility must be managed by the teacher from a dual perspective, both individual and shared, thus increasing the possibilities of transfer towards intrinsic motivation in carrying out tasks (Adé et al., 2018). This is related to decision making, which, articulated in a shared way, increases satisfaction with success in the task, also improving the school climate and the cultural environments themselves (Perry-Hazan & Somech, in press), since it allows for the establishment in the classroom of the habit of acceptance towards others, regardless of their level of ability, their physical and/or psychological characteristics, their origin and their socioeconomic level.

Closely related to this is the promotion of responsibility through specific elements of cooperative learning such as positive interdependence, as well as promoting interaction and shared help, which result in less perceived violence, and the promotion of autonomous learning (Shi & Han, 2019). In relation to the cooperative learning model, the existing literature in Physical Education is diverse, having shown benefits in relation to the scope of students' social interactions (Hortigüela-Alcalá, Fernández-Río, González-Calvo, et al., 2019), the professional identity of future teachers (Hortigüela-Alcalá et al., 2020), understanding and learning (Darnis & Lafont, 2015) and the improvement of intrinsic motivation towards tasks (Fernández-Río et al., 2017).

Regarding the second of the objectives, related to the differences in psychosocial variables depending on sex and educational stage, differences were found concerning the educational stage, while in the case of sex there was similar behaviour between boys and girls. In this sense, the results reflect how there were only differences in the independent variable of educational stage, while the sex variable and the stage-sex interaction did not present significant values. At the level of the educational stage, significant differences were found for responsibility, autonomous motivation and for violence. Specifically, the Primary Education stage presents significant results when compared to both Secondary and Baccalaureate-Training Cycles, always presenting higher means for each of the dependent variables, except for violence. This result is of great importance, since it allows reflection and the taking of pedagogical measures depending on the stage at which the student is. In this way, the second hypothesis proposed is confirmed, since the average levels of the different psychosocial variables are similar regarding sex, but differ when it comes to the educational stage, showing worse values of responsibility, satisfaction of basic psychological needs, motivation, autonomy and violence for older ages. From this a series of implications can be derived for educational centres and teachers, such as: (1) delimit regulations of codes of conduct and disciplinary transversal to different subjects, establishing a connection between the Primary and Secondary stages; (2) propose, in the Secondary stage, methodologies that integrate personal and social responsibility as an essential element; and, (3) establish collective tasks that favour the heterogeneity of groups, promoting responsibility to aid achievement, both individual and collective.

These data contrast with those of some previous studies in which it was shown how girls have greater responsibility than boys, not only in the academic field, but in relation to family commitments (Redmon et al., 2022). This difference is based on cultural, family and psychoevolutionary factors, which reflect how, from society, often subliminally, girls are encouraged to assume more responsibility and commitment, especially academic, penalizing and judging them more than others (Haugan et al., 2021). It has been shown how from the family unit there is greater pressure, in many cases unconscious or assumed, concerning the generation of responsibility towards academic performance, which in many cases causes them to have to stop practicing other activities, such as sports. (Abadi & Gill, 2020). In any case, the sociocultural and economic level of the families directly influences the academic performance of their children, with the students who repeat the most grades and have the worst record being those who come from families with fewer resources (Bellibas, 2016).

Considering the educational stages, the results of the present study are in accordance with those presented by Kipp and Bolter (2020) and Manzano-Sánchez (2021), who conclude that the levels of responsibility, motivation and school climate are higher in the educational stage of Primary. Therefore, it seems that the didactic approaches carried out in the early stages, due to their more playful and less demanding nature, favour the motivation, involvement and social climate of the student, thus reducing violence, both generated and perceived. However, in the Secondary stage, in which adolescence flourishes, students give a lot of importance to the relationship with their peers (sometimes excessive), something that causes ego orientations to appear, which sometimes results in unstructured classroom climates, and the possibility of bullying (Hortigüela-Alcalá, Fernández-Río, González-Calvo et al., 2019). Furthermore, it has been shown how in the early stages of development it is parents who largely shape children's behaviour, due to the greater impact they have on the construction of their personality (Saracho, 2023).

Therefore, following this idea, pedagogical models such as Personal and Social Responsibility, applied longitudinally, obtain improvements in various variables, in addition to responsibility, such as the satisfaction of basic psychological needs or more self-determined motivation (Manzano-Sánchez & Valero-Valenzuela, 2019). Specifically, in Physical Education, it is essential that this model is worked on from the initial training of teachers, connecting motor skills with the values of respect and acceptance of others. Studies such as that of Meléndez et al. (2021) demonstrate how novice teachers value it very positively, especially as a way to develop student values throughout life. In this sense, teachers state that the model allows the identification of the most common emotions among students, and as a consequence favours actions to increase commitment in class and the adoption of adaptive personal and social responsibilities, in areas both within and outside of school (Simonton & Shiver, 2021).

ConclusionsIt can be stated that responsibility has a predictive value on the school climate and perceived violence, and that it occurs regardless of sex but not educational stage, with the satisfaction of basic psychological needs and autonomous motivation acting as mediators. The youngest students, belonging to the Primary stage, present better values in terms of responsibility, satisfaction of basic psychological needs, autonomous motivation, classroom climate and violence compared to the Secondary, Baccalaureate and Training Cycles stages. This leads to the need to propose work focused on improving responsibility in the Secondary, Baccalaureate and Training Cycles stage for the prevention of violent behavior and the improvement of the school climate.

When identifying the limitations of the present study, it should be noted that the model presented is one of many that can be proposed. Although the fit and goodness indices in general they have been adequate, there are also certain values that have not been adequate, such as the value of Box's test for homogeneity of variances. Furthermore, due to its transversal and correlational nature, the model reflects a specific section in time and doesn’t support any causal explanations. Other types of samples can also be used, which respond to a broader spectrum of various educational centres and autonomous communities.

As suggestions for future research, it would be interesting to promote the responsibility of students in a variety of subjects, applying active methodologies that allow encouragement of this variable, and with it, the satisfaction of the three basic psychological needs and autonomous motivation. Hybridization with other models, such as cooperative learning, can also be considered, checking the social effects that this may entail, given that no research in this sense has been contemplated. At the same time, one can try to replicate research similar to the current one, testing theoretical models that take into account controlled motivation and demotivation, in addition to autonomous motivation (Sánchez-Oliva et al., 2014). It is also desirable to consider the measurement of other mediating variables, such as the emotional sphere, the attitude towards the subject of Physical Education or the satisfaction with the learning acquired. Finally, it is possible to propose courses aimed at teachers to apply active methodologies that provide them with tools to promote life skills and maintain a good school climate, as well as useful elements for conflict resolution.

FundingThis work has received funding from the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports, through a FPU contract (16/00062).