Schools play a fundamental role in promoting psychological and academic adjustment during adolescence. Given that the majority of students in the classrooms are of Spanish and Moroccan origin, the main objective of this study was to conduct a cross-cultural Spain-Morocco analysis of scholar, clinical, and personal maladjustment, taking into account both sex and age. In order to ensure a valid assessment, a preliminary objective was set to adapt and evaluate the psychometric properties of the Behavioural Assessment System for Children and Adolescents (BASC-S3) in the Moroccan context. A total of 1,707 students participated, 941 residing in Spain and 766 in Morocco, aged between 11 and 19 years. The results demonstrated adequate psychometric properties for both the Spanish and Moroccan versions of the questionnaire, along with sex and age invariance within each country and between the two countries. Comparisons within each country revealed few differences based on sex and age. However, comparisons between countries have revealed lower levels of scholar, clinical, and personal maladjustment in Spain than in Morocco. Considering these cultural differences may help to design more effective preventive interventions and improve psychological assessment and care.

Los centros educativos desempeñan un papel fundamental en la promoción del ajuste psicológico y escolar durante la adolescencia. Dado que el alumnado mayoritario en las aulas es de origen español y marroquí, este estudio ha tenido como objetivo principal hacer un análisis cross-cultural España-Marruecos del desajuste escolar, clínico y personal, atendiendo al sexo y la edad. Para garantizar una correcta evaluación, como objetivo preliminar se ha planteado adaptar y evaluar las propiedades psicométricas del Sistema de Evaluación de la Conducta de Niños/as y Adolescentes (BASC-S3) en el contexto marroquí. Han participado 1.707 estudiantes, 941 residentes en España y 766 en Marruecos, con edades entre los 11 y los 19 años. Los resultados han mostrado adecuadas propiedades psicométricas de las versiones española y marroquí del cuestionario, junto invarianza en función del sexo y la edad dentro de cada país y entre países. Las comparaciones dentro de cada país han revelado pocas diferencias en función del sexo y la edad. Sin embargo, las comparaciones entre países, han puesto de manifiesto menores niveles de desajuste escolar, clínico y personal en España que Marruecos. La consideración de estas diferencias culturales puede ayudar a diseñar intervenciones preventivas más eficaces y mejorar la evaluación y atención psicológica.

Throughout life, human beings progress through several developmental stages, with adolescence being one of the most critical due to the many physical, social, and psychological changes experienced (Bernaras et al., 2017). This transitional period between childhood and adulthood, spanning approximately from 10 to 19 years of age (World Health Organization [WHO], 2014), presents significant opportunities but also stressors, which, if not properly managed, can increase the risk of maladjustment. Safeguarding and promoting young people’s mental health within educational environments should be a priority (Zabaleta et al., 2022) for two primary reasons. Firstly, there is a high likelihood that common mental disorders in adulthood first manifest during childhood and adolescence (Solmi et al., 2022). Secondly, there is a tendency to misdiagnose and undertreat emotional symptoms in adolescents (Garaigordobil et al., 2023), which impacts multiple areas of young people’s lives (personal, family, school, social, etc.) in the short, mid, and long term (Arrondo et al., 2022). It is therefore essential to enhance assessment procedures for the early detection and identification of psychological and socio-educational difficulties or challenges and positive factors that promote adolescents’ adjustment, using comprehensive, reliable, and culturally adapted tools to facilitate informed decision-making. This can aid in both preventing maladjustment and promoting and evaluating interventions' effectiveness (Casares et al., 2024).

The first challenge encountered in quality assessments is that, to date, there is no universally accepted concept of psychosocial adjustment within the scientific community (Londono & McMillan, 2015). A review of the literature reveals the coexistence of two approaches (Lent, 2004). One approach defines adjustment by the absence of symptomatology, focusing research on psychological deficits and psychopathological problems. The other approach highlights the positive aspects of adjustment, investigating skills and abilities related to optimal personal, school, or social functioning and life satisfaction (Piqueras et al., 2019).

In 1992, Reynolds and Kamphaus proposed a relevant model, articulated around three key dimensions for adolescents, combining both perspectives. These dimensions are: (1) clinical maladjustment, which includes depression, anxiety, social stress, atypicality, external locus of control and somatisation. This dimension is particularly relevant given the overall prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents, estimated to range between 15.5 and 31% (Sacco et al., 2022; Silva et al., 2020); (2) school maladjustment, understood as negative attitudes towards school and teachers, feelings of inadequacy in response to academic demands, and extreme sensation-seeking. These factors are receiving increased attention, as students’ psychological and affective characteristics account for almost 50% of the variance in academic success (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2010); and (3) personal adjustment, which includes aspects such as family and peer relationships, self-esteem, and self-confidence, all of which are essential for adolescents’ optimal functioning (Bully et al., 2019; Robins et al., 2002).

It is also recognised that clinical, school and personal maladjustment are interrelated, with most psychological disorders causing emotional, cognitive, or social impairments. Adolescents with psychological disorders face an increased risk of negative school experiences, potentially leading to early school dropout (Esch et al., 2014). Numerous studies have also shown that low school satisfaction is associated with health-risk behaviours, such as substance use, a more negative perception of one’s health, and a higher incidence of somatic symptoms (Cosma et al., 2023).

Another important issue is the percentage of international students enrolled in the Spanish non-university education system, which was around 12.2% of the total student body for the 2023/24 academic year (Instituto Nacional de Estadística [INE], 2024). For this reason, the commitment to mental health in educational contexts must transcend cultural boundaries and adopt a global approach that recognises and values diverse experiences and perspectives. Furthermore, various studies and institutional reports indicate that migrants face significant adaptive challenges in the socio-cultural adjustment process to their new country of residence (González-Rábago, 2014). Several studies have pointed out that for migrant minors, this process may involve a period of heightened vulnerability to developing psychological and emotional problems (Rodríguez et al., 2002; Siguán, 1998), which warrants special attention.

A student integrated into the education system, both academically and socio-emotionally, is more likely to reach their full potential. However, the migrant population faces multiple obstacles that hinder this development, including the lack of linguistically and culturally adapted assessment tools. In this context, intercultural studies provide a valuable perspective, especially those considering the Moroccan population, as it represents the largest migrant population in Spain. During the last academic year, of the 1,066,875 international students, 200,439 (18.79%) were Moroccan (Instituto Nacional de Estadística [INE], 2024). This figure includes only those students who still hold Moroccan nationality. Including second-generation students (born in Spain to Moroccan parents) would further increase this proportion, as many of these students have Spanish nationality but come from immigrant Moroccan families. This makes Moroccan students one of the main groups of international students in Spain.

Several studies have examined psychological and personal adjustment during adolescence in Arab contexts such as Egypt (Seleem et al., 2023), Algeria (Petot et al., 2008), Tunisia (Chahed, 2010), and Qatar (Al-Hendawi et al., 2016), using data provided by parents via the Child Behaviour Checklist for Children (CBCL). Studies in Algeria and Tunisia suggest that adolescents may have higher scores on the CBCL (Chahed, 2010; Petot et al., 2008) compared to adolescent populations in other countries, whereas the Egyptian study found no differences (Seleem et al., 2023), underscoring variability across different Arab populations. However, studies focusing on Moroccan adolescents are scarce. As Zouini et al. (2019) noted, ‘despite its importance, the mental health and well-being of Moroccan adolescents is literally unexplored’ (p. 236). These authors found rates of antisocial and aggressive behaviour in Moroccan adolescents similar to those reported in other countries. Still, they highlighted the lack of internationally comparative data, indicating a need for further studies to describe cultural differences in adolescent populations. Cortés-Denia et al. (2020) explained that, within the Moroccan socio-cultural context, adolescence is not viewed as an age but rather as a biologically-based transitional stage. The lack of validated instruments for measuring psychological variables has left a gap in understanding the psychological adjustment of Moroccan adolescents. The limited studies on cross-cultural differences between Spanish and Moroccan adolescents focus exclusively on migrant populations (Sánchez-Castelló et al., 2022; Soriano, 2014), and no study has been found to explore differences in psychological and personal adjustment between adolescents in Spain and Morocco.

The same is true for school maladjustment. No data have been found comparing attitudes towards teachers, school, or feelings of inadequacy in response to academic demands between the two countries. In terms of school failure in Spain, the number of adolescents who do not meet the expected academic standards increases throughout Compulsory Secondary Education (ESO): 12.1% of students are behind in the first year and 24.5% in the fourth, with 95.9% completing school at age 16, and 74.9% at age 19. Moreover, 80.9% obtain the ESO diploma, and only 55.7% obtain the Highschool diploma (Ministry of Education, Vocational Training and Sport [MEFD], 2024). In Morocco, educational problems have been prioritised due to the lack of universal schooling, low teaching quality, inequality in educational access, and high dropout rates. According to the World Bank (2014), the secondary education completion rate in Morocco is around 65%. However, in rural areas, enrolment rates are lower, with only 20% of students enrolled in secondary education compared to 64% in urban areas.

Additionally, it is important to investigate the influence of gender and age within and between countries, as years of study have yielded conflicting findings on adjustment differences during adolescence attributable to these factors. Regarding gender differences in clinical and personal maladjustment, some studies indicate that during adolescence, males and females exhibit problems in distinct ways, with females showing higher rates of internalising symptoms (depression, anxiety, stress, somatic complaints, low self-esteem, relationship problems, etc.) (Cosma et al., 2023; Moreno et al., 2016; Salk et al., 2017) and males displaying externalising symptoms (verbal aggression, delinquent behaviour, conduct disorders, etc.) (Sarracino et al., 2011). However, some research also suggests that the differences between males and females are minimal and that their similarities are more pronounced (Bernaras et al., 2017; Hyde, 2005; Orth et al., 2018). In terms of school maladjustment, some studies report higher maladjustment in males (Johnson et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2008), while others find that although females perform better academically, they also experience greater dissatisfaction and distress (Pomerantz et al., 2002), and some studies find no significant gender differences (e.g., Oramah, 2014). As for age-related differences in clinical maladjustment, some authors report that such differences increase with age (Compas et al., 2004; Cosma et al., 2023; Moreno et al., 2016). Other studies suggest this increase is less significant (Bernaras et al., 2017; Moksnes et al., 2010) or they find no differences (Jaureguizar et al., 2015). School maladjustment appears to increase as adolescents grow older (Jaureguizar et al., 2015). Lastly, personal adjustment, self-esteem and self-confidence are reported to improve with age (Naranjo, 2007; Orth et al., 2018).

The present studyThe general objective of this study is to compare the psychosocial adjustment of the adolescent population in Spain and Morocco, two geographically close but culturally distinct regions. For this purpose, the study sets out the following specific objectives: (1) to linguistically and culturally adapt the Behaviour Assessment System for Children (BASC-S3; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 1992) to the Moroccan context (in both French and Arabic); (2) to analyse the psychometric properties of the BASC-S3 in a sample of Moroccan adolescents within their country of origin; (3) to examine the test’s invariance across sex, age, and country of origin to assess any potential biases related to these variables; and (4) to identify similarities and differences between Spain and Morocco in school, clinical, and personal maladjustment, considering both the sex and age of the adolescents.

Concerning the hypotheses, we expect to: (1) confirm that the factor structure and reliability of the Moroccan version of the BASC-S3 are comparable to those found in the original Spanish and Basque versions; (2) demonstrate the test’s sex, age, and language invariance in relation; (3) to observe that in both Spain and Morocco, females obtain lower scores than males in school maladjustment and higher scores in clinical and personal maladjustment, with low to moderate effect sizes and moderate age-related differences; and (4) to identify differences between Spain and Morocco in school, clinical, and personal maladjustment, although it is not possible to predict the direction of these differences due to the lack of prior studies.

The aim is to expand our understanding of the factors influencing adolescent adjustment in underrepresented socio-cultural contexts. This can contribute to reducing prejudice and stereotypes by enabling a scientific and objective perspective on cultural differences and by supporting more effective interventions within the school environment.

MethodDesignThis study is descriptive, correlational, cross-sectional, and prospective.

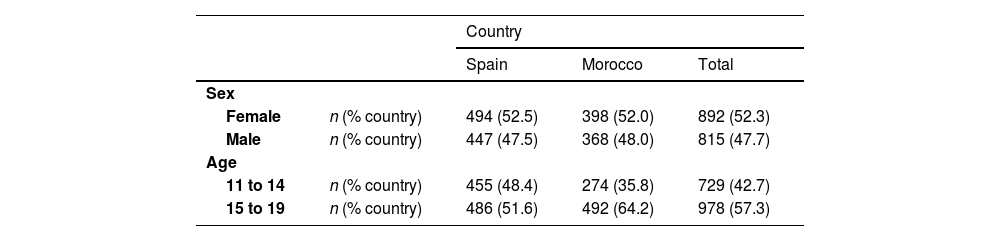

ParticipantsThe study was cross-cultural and multicentre. Incidental sampling was conducted in two stages: first, in Spain and then, in Morocco. To achieve a heterogeneous sample, we contacted public, subsidised and private schools in provincial capitals and smaller towns. A total of 1,707 students participated: 941 residents in Spain, from four different schools (two public and two subsidised), and 766 in Morocco, attending five different schools (all private) (see Table 1). The participants’s age ranged from 11 to 19 years (M = 14.88, SD = 1.72). Although adolescence is not a continuous, synchronous, and uniform process for all individuals, in the present study, we decided to divide the sample into two age ranges corresponding to early adolescence and mid-late adolescence. This division was based on the well-established consensus that psychosocial development in adolescence generally follows a progressive pattern with three phases: early (10-14 years), middle (15-17 years), and late (18-19 years) adolescence (Hornberger, 2006). A total of 93.2% of participants were from urban areas, and the majority had a medium-high socio-economic status.

InstrumentThe Behavioural Assessment System for Children and Adolescents (BASC; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 1992) was used in its self-report version for adolescents aged 12 to 18 years (S3), adapted to Spanish by González et al. (2004) and to Basque by Bernaras et al. (2017). This inventory consists of 185 items rated as true or false. The items are grouped into 14 subdimensions assessing clinical and adaptive issues. The clinical subdimensions are: negative attitude towards school (10 items), negative attitude towards teachers (9 items), sensation-seeking (14 items), atypicality (16 items), locus of control (14 items), somatisation (9 items), social stress (13 items), anxiety (15 items), depression (14 items), and sense of inadequacy (13 items). The four adaptive subdimensions are: interpersonal relationships (15 items), relationships with parents (9 items), self-esteem (8 items), and self-confidence (9 items). These 14 subdimensions are grouped into three global dimensions: school maladjustment, clinical maladjustment and personal adjustment. Both the Spanish and Basque adaptations of the test have shown adequate psychometric properties, with a good fit of the three-dimensional second-order model composed of the subdimensions, and high internal consistency, with coefficients ranging from .84 to .90 in the Spanish version (González et al., 2004) and from .83 to .94 in the Basque version (Bernaras et al., 2017).

ProcedureThe study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU) (file M10_2018_185). Following the guidelines of the International Test Commission (ITC, 2017), the intellectual property rights of the questionnaires were checked. The process of linguistic, conceptual and cultural adaptation was carried out entirely in Morocco following three steps: (1) linguistic adaptation of the instrument: a bilingual Moroccan translator with experience in education produced the first version of the instrument in French and Moroccan Arabic. A second translator validated it following a back-translation procedure. Similarities and discrepancies were assessed, taking into account the list for the quality control of the translation-adaptation of the items of Hambleton and Zenisky (2011); (2) adaptation to the cultural context: This was carried out by expert judgment in a multidisciplinary committee composed of a methodologist, three teachers, a school principal and a mother. The relevance of the content of the tests and their local comprehensibility were evaluated; and (3) Analysis of metric properties. For this purpose, we contacted the school management teams by telephone or e-mail and made appointments for a brief meeting to explain the aims of the study and the procedure to be followed if the managers were interested in participating., We established the conditions for sending the informed consent form to the families with the schools whose managers agreed to participate. Once these forms had been obtained, we assessed the pupils. The school management could choose the language in which to use the questionnaire: in Spain, Spanish or Basque, and in Morocco, French or Arabic. In Spain, 92% chose the application in Basque and 8% in Spanish. In Morocco, they all chose French. In both countries, the majority choice coincided with the language used in the schools. We administered tests in groups, in the usual classrooms, during school hours and always in the presence of a member of the research team. Students took between 20 and 30 minutes to complete the tests.

Data analysisFirst, we analysed the presence and type of missing data and outliers. Secondly, we extracted 40% of the participants to analyse the psychometric properties of the questionnaire. Third, we studied the unidimensionality of each of the 14 primary subdimensions through confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) using the weighted least squares robust mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimation method, reliable with small samples and valid for dichotomous items. Their reliability was assessed through the Kuder-Richardson 20 (KR2o) and McDonald omega (ω) coefficients. Fourthly, given that the subdimensions were psychometrically adequate, we calculated descriptive statistics for the sum of the scores in the primary subdimensions (% floor, % ceiling, mean and its 95% confidence interval, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis and homogeneity index). Fifthly, we analysed the relationship between the test’s subdimensions and their agreement with the theoretical model used for its construction through AFCs (unidimensional—a single global maladjustment score—, two-dimensional—clinical scales-adaptive scales—, and three-dimensional —school, clinical and personal maladjustment) with the same estimation method, given robustness to the lack of normality in the distribution of the scores in the subdimensions. The assessment of the fit of the models to the data was based on the value of the chi-square/df ratio (χ2/df), together with information provided by the incremental goodness-of-fit index (CFI), the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) and its standardisation (SRMS). Models with values equal to or less than 5 in the ratio χ2/df, equal to or greater than .95 in CFI, and equal to or less than .08 in RMSEA and SRMS were considered acceptable (Hu & Bentler, 1999). For the choice between alternative models, the Akaike information criterion (AIC) was used (the smaller the better). The KR20 and ω reliability coefficients were also calculated for each dimension, thus obtaining indicators of the scores’ internal consistency in the two language versions. The minimum good value was .70 for both indicators.

Finally, we analysed the possible cross-cultural differences and described the questionnaire scores based on the dimensionality in two steps. In the first step, we performed a stepwise invariance analysis of the instruments between groups (by gender, age and country), taking into account their asymmetric nature (Tse et al., 2023). As an acceptance criterion for metric, scalar and strict invariance models, we used the variation in fit indices; that is, the change in CFI (CFI1 - CFI2 < .01), in RMSEA (RMSEA2 - RMSEA1 < .015), and in SRMR (SRMR2 - SRMR1 < .030) between nested models (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). In the second step, using 60% of the participants not included in the validation analyses, we calculated the differences in latent mean scores derived from the above models as a function of country, gender and age. Effect sizes were assessed using Cohen's d parameter, splitting the latent mean difference by the pooled standard deviation across countries (Hong et al., 2003), according to the procedure described by Hancock (2001). The Spanish sample was established as the reference group, so its latent mean values were set to zero. Values lower than 0.20 were considered small, while values higher than 0.8 were considered large (Cohen, 1988). The analyses were carried out in the R environment (R Development Core Team, 2022).

ResultsAdaptation processThe process of linguistic adaptation went smoothly. The French version can be found in Appendix 1.

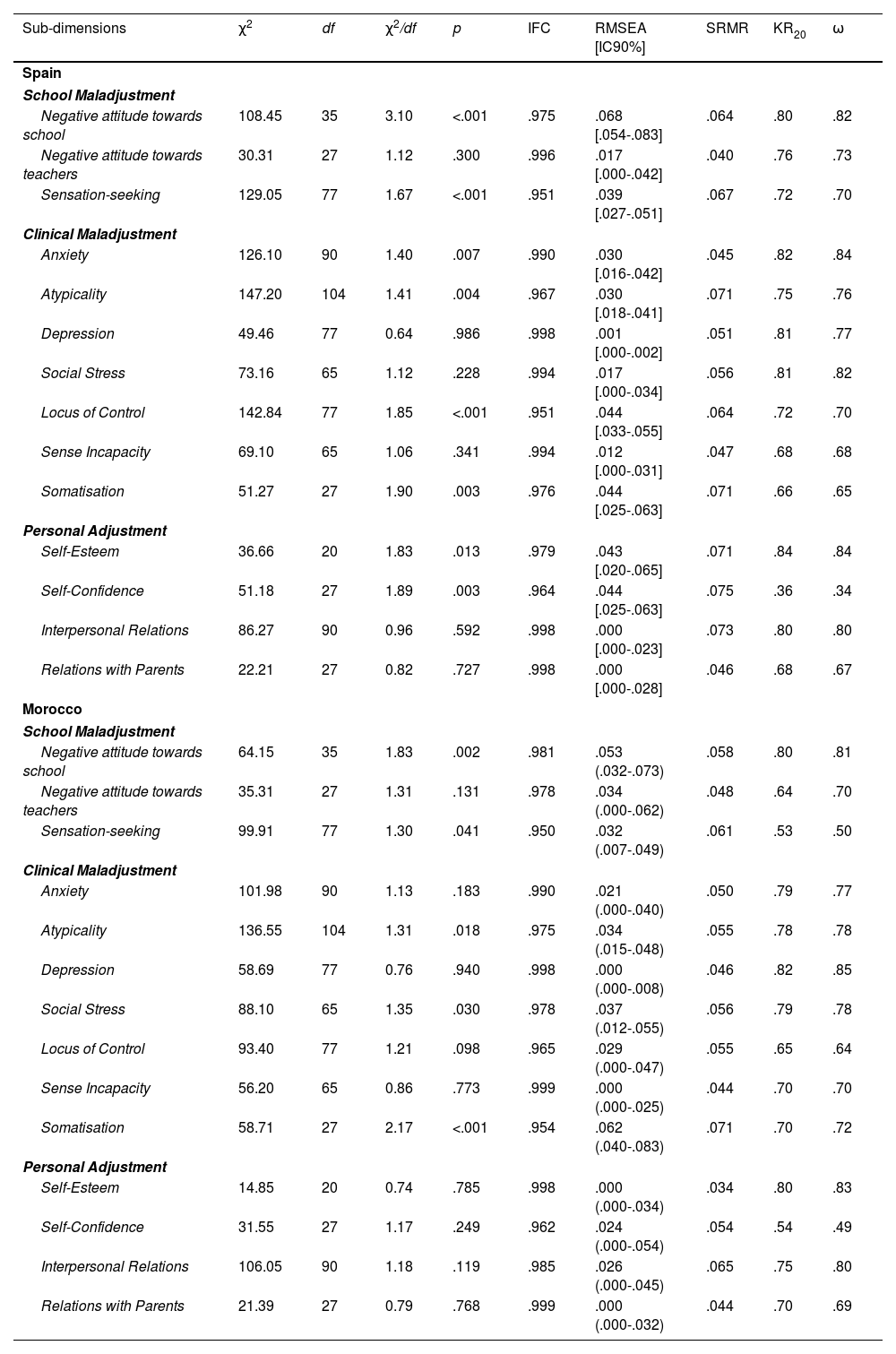

Psychometric properties of the BASC-3S in Spain and MoroccoDespite some missing values, they did not exceed 8% of the cases in any item or subdimension, nor did they follow a defined pattern. Therefore, we decided not to use imputation procedures to replace them. The fit indices to the unidimensional model and the internal consistency coefficients obtained (Table 2) support the psychometric adequacy of the 14 sub-dimensions of the BASC-S3.

Fit Indices of the unidimensional model of the 14 sub-dimensions of the BASC-S3 to the Spanish and Moroccan adolescent population

| Sub-dimensions | χ2 | df | χ2/df | p | IFC | RMSEA [IC90%] | SRMR | KR20 | ω |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain | |||||||||

| School Maladjustment | |||||||||

| Negative attitude towards school | 108.45 | 35 | 3.10 | <.001 | .975 | .068 [.054-.083] | .064 | .80 | .82 |

| Negative attitude towards teachers | 30.31 | 27 | 1.12 | .300 | .996 | .017 [.000-.042] | .040 | .76 | .73 |

| Sensation-seeking | 129.05 | 77 | 1.67 | <.001 | .951 | .039 [.027-.051] | .067 | .72 | .70 |

| Clinical Maladjustment | |||||||||

| Anxiety | 126.10 | 90 | 1.40 | .007 | .990 | .030 [.016-.042] | .045 | .82 | .84 |

| Atypicality | 147.20 | 104 | 1.41 | .004 | .967 | .030 [.018-.041] | .071 | .75 | .76 |

| Depression | 49.46 | 77 | 0.64 | .986 | .998 | .001 [.000-.002] | .051 | .81 | .77 |

| Social Stress | 73.16 | 65 | 1.12 | .228 | .994 | .017 [.000-.034] | .056 | .81 | .82 |

| Locus of Control | 142.84 | 77 | 1.85 | <.001 | .951 | .044 [.033-.055] | .064 | .72 | .70 |

| Sense Incapacity | 69.10 | 65 | 1.06 | .341 | .994 | .012 [.000-.031] | .047 | .68 | .68 |

| Somatisation | 51.27 | 27 | 1.90 | .003 | .976 | .044 [.025-.063] | .071 | .66 | .65 |

| Personal Adjustment | |||||||||

| Self-Esteem | 36.66 | 20 | 1.83 | .013 | .979 | .043 [.020-.065] | .071 | .84 | .84 |

| Self-Confidence | 51.18 | 27 | 1.89 | .003 | .964 | .044 [.025-.063] | .075 | .36 | .34 |

| Interpersonal Relations | 86.27 | 90 | 0.96 | .592 | .998 | .000 [.000-.023] | .073 | .80 | .80 |

| Relations with Parents | 22.21 | 27 | 0.82 | .727 | .998 | .000 [.000-.028] | .046 | .68 | .67 |

| Morocco | |||||||||

| School Maladjustment | |||||||||

| Negative attitude towards school | 64.15 | 35 | 1.83 | .002 | .981 | .053 (.032-.073) | .058 | .80 | .81 |

| Negative attitude towards teachers | 35.31 | 27 | 1.31 | .131 | .978 | .034 (.000-.062) | .048 | .64 | .70 |

| Sensation-seeking | 99.91 | 77 | 1.30 | .041 | .950 | .032 (.007-.049) | .061 | .53 | .50 |

| Clinical Maladjustment | |||||||||

| Anxiety | 101.98 | 90 | 1.13 | .183 | .990 | .021 (.000-.040) | .050 | .79 | .77 |

| Atypicality | 136.55 | 104 | 1.31 | .018 | .975 | .034 (.015-.048) | .055 | .78 | .78 |

| Depression | 58.69 | 77 | 0.76 | .940 | .998 | .000 (.000-.008) | .046 | .82 | .85 |

| Social Stress | 88.10 | 65 | 1.35 | .030 | .978 | .037 (.012-.055) | .056 | .79 | .78 |

| Locus of Control | 93.40 | 77 | 1.21 | .098 | .965 | .029 (.000-.047) | .055 | .65 | .64 |

| Sense Incapacity | 56.20 | 65 | 0.86 | .773 | .999 | .000 (.000-.025) | .044 | .70 | .70 |

| Somatisation | 58.71 | 27 | 2.17 | <.001 | .954 | .062 (.040-.083) | .071 | .70 | .72 |

| Personal Adjustment | |||||||||

| Self-Esteem | 14.85 | 20 | 0.74 | .785 | .998 | .000 (.000-.034) | .034 | .80 | .83 |

| Self-Confidence | 31.55 | 27 | 1.17 | .249 | .962 | .024 (.000-.054) | .054 | .54 | .49 |

| Interpersonal Relations | 106.05 | 90 | 1.18 | .119 | .985 | .026 (.000-.045) | .065 | .75 | .80 |

| Relations with Parents | 21.39 | 27 | 0.79 | .768 | .999 | .000 (.000-.032) | .044 | .70 | .69 |

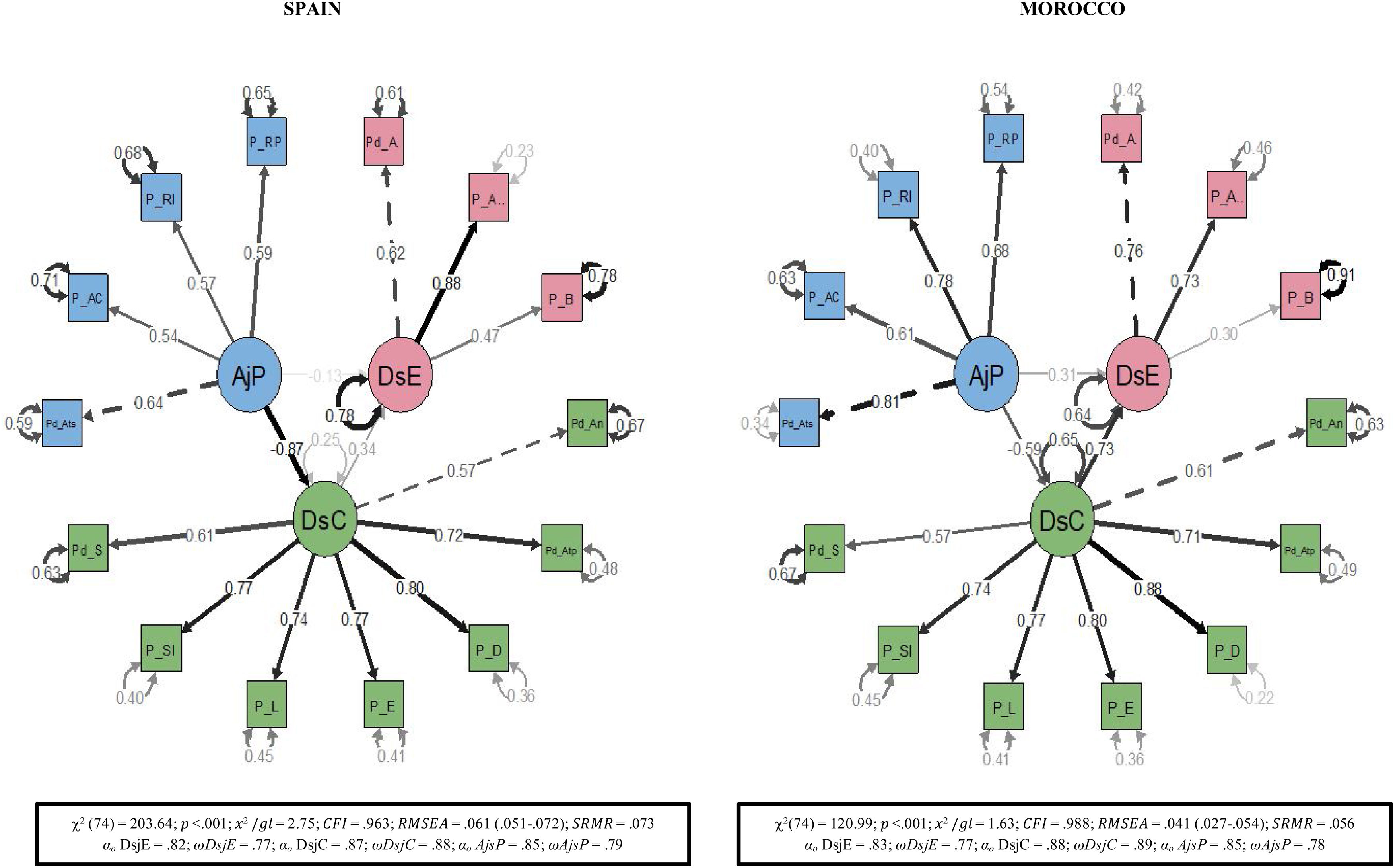

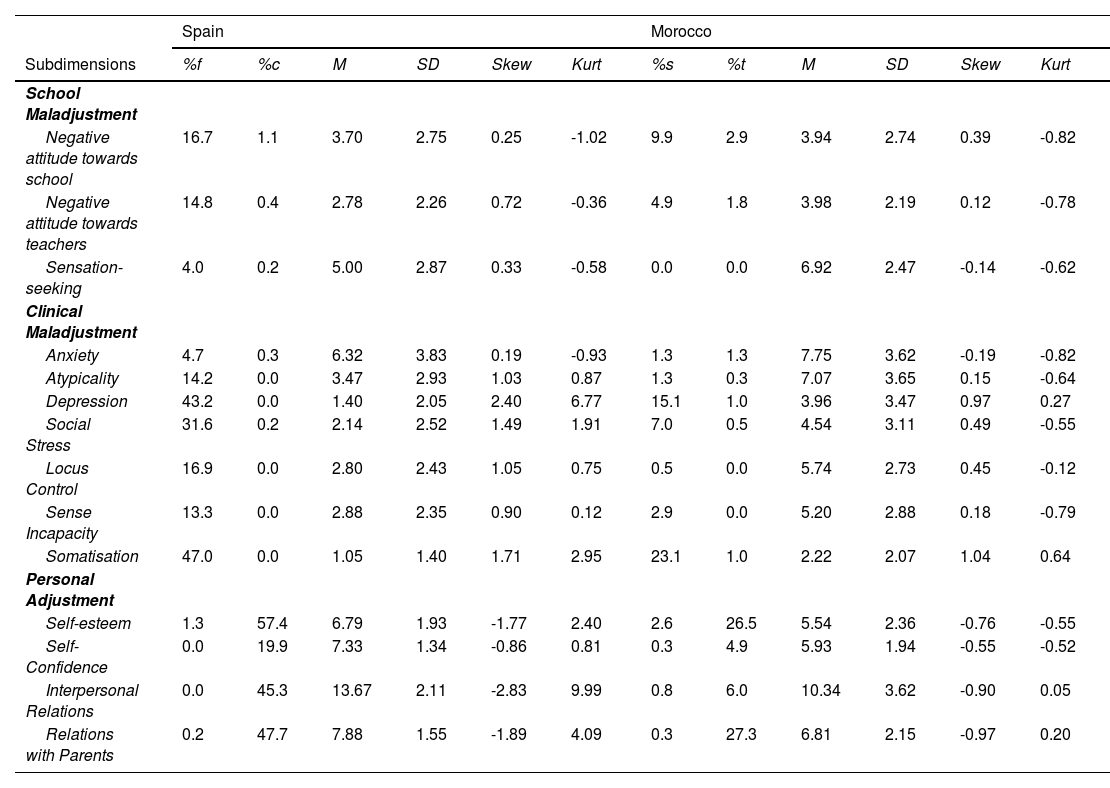

Table 3 shows the formal description of the sub-dimensions that make up the final questionnaire in Spain and Morocco. In both countries, the averages were well below the theoretical mean in all the negative aspects evaluated and above it in the positive aspects. Skewness and kurtosis statistics, together with the presence of floor and ceiling effects, indicated a distribution of scores with a tendency to accumulate in the asymptomatic pole. All items had homogeneity indices equal to or above the accepted minimum of .30. When the internal structure of the questionnaire was tested, both in Spain and Morocco, the model that showed the best results was the three correlated factor model (as opposed to the unidimensional and the two-dimensional models) with values of the ratio χ2/df below 5, CFI above .95, and RMSEA and SRMR below .08. As for the relationships between factors, in Spain the association was highly negative between personal adjustment and clinical maladjustment, moderately negative between personal adjustment and school maladjustment, and moderately positive between school maladjustment and clinical maladjustment. In contrast, in Morocco, the association between school maladjustment and clinical maladjustment was strong and positive. See Figure 1 for more details. Regarding reliability, internal consistency was high in all three dimensions in both countries, with all coefficients exceeding .70.

Descriptive statistics for the 14 subdimensions of the adapted version of the BASC-S3 to the Spanish and Moroccan adolescent populations

| Spain | Morocco | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subdimensions | %f | %c | M | SD | Skew | Kurt | %s | %t | M | SD | Skew | Kurt |

| School Maladjustment | ||||||||||||

| Negative attitude towards school | 16.7 | 1.1 | 3.70 | 2.75 | 0.25 | -1.02 | 9.9 | 2.9 | 3.94 | 2.74 | 0.39 | -0.82 |

| Negative attitude towards teachers | 14.8 | 0.4 | 2.78 | 2.26 | 0.72 | -0.36 | 4.9 | 1.8 | 3.98 | 2.19 | 0.12 | -0.78 |

| Sensation-seeking | 4.0 | 0.2 | 5.00 | 2.87 | 0.33 | -0.58 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.92 | 2.47 | -0.14 | -0.62 |

| Clinical Maladjustment | ||||||||||||

| Anxiety | 4.7 | 0.3 | 6.32 | 3.83 | 0.19 | -0.93 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 7.75 | 3.62 | -0.19 | -0.82 |

| Atypicality | 14.2 | 0.0 | 3.47 | 2.93 | 1.03 | 0.87 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 7.07 | 3.65 | 0.15 | -0.64 |

| Depression | 43.2 | 0.0 | 1.40 | 2.05 | 2.40 | 6.77 | 15.1 | 1.0 | 3.96 | 3.47 | 0.97 | 0.27 |

| Social Stress | 31.6 | 0.2 | 2.14 | 2.52 | 1.49 | 1.91 | 7.0 | 0.5 | 4.54 | 3.11 | 0.49 | -0.55 |

| Locus Control | 16.9 | 0.0 | 2.80 | 2.43 | 1.05 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 5.74 | 2.73 | 0.45 | -0.12 |

| Sense Incapacity | 13.3 | 0.0 | 2.88 | 2.35 | 0.90 | 0.12 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 5.20 | 2.88 | 0.18 | -0.79 |

| Somatisation | 47.0 | 0.0 | 1.05 | 1.40 | 1.71 | 2.95 | 23.1 | 1.0 | 2.22 | 2.07 | 1.04 | 0.64 |

| Personal Adjustment | ||||||||||||

| Self-esteem | 1.3 | 57.4 | 6.79 | 1.93 | -1.77 | 2.40 | 2.6 | 26.5 | 5.54 | 2.36 | -0.76 | -0.55 |

| Self-Confidence | 0.0 | 19.9 | 7.33 | 1.34 | -0.86 | 0.81 | 0.3 | 4.9 | 5.93 | 1.94 | -0.55 | -0.52 |

| Interpersonal Relations | 0.0 | 45.3 | 13.67 | 2.11 | -2.83 | 9.99 | 0.8 | 6.0 | 10.34 | 3.62 | -0.90 | 0.05 |

| Relations with Parents | 0.2 | 47.7 | 7.88 | 1.55 | -1.89 | 4.09 | 0.3 | 27.3 | 6.81 | 2.15 | -0.97 | 0.20 |

% floor effect (%f), % ceiling effect (%c), arithmetic mean (M), standard deviation (SD), skewness (Skew), kurtosis (Kurt).

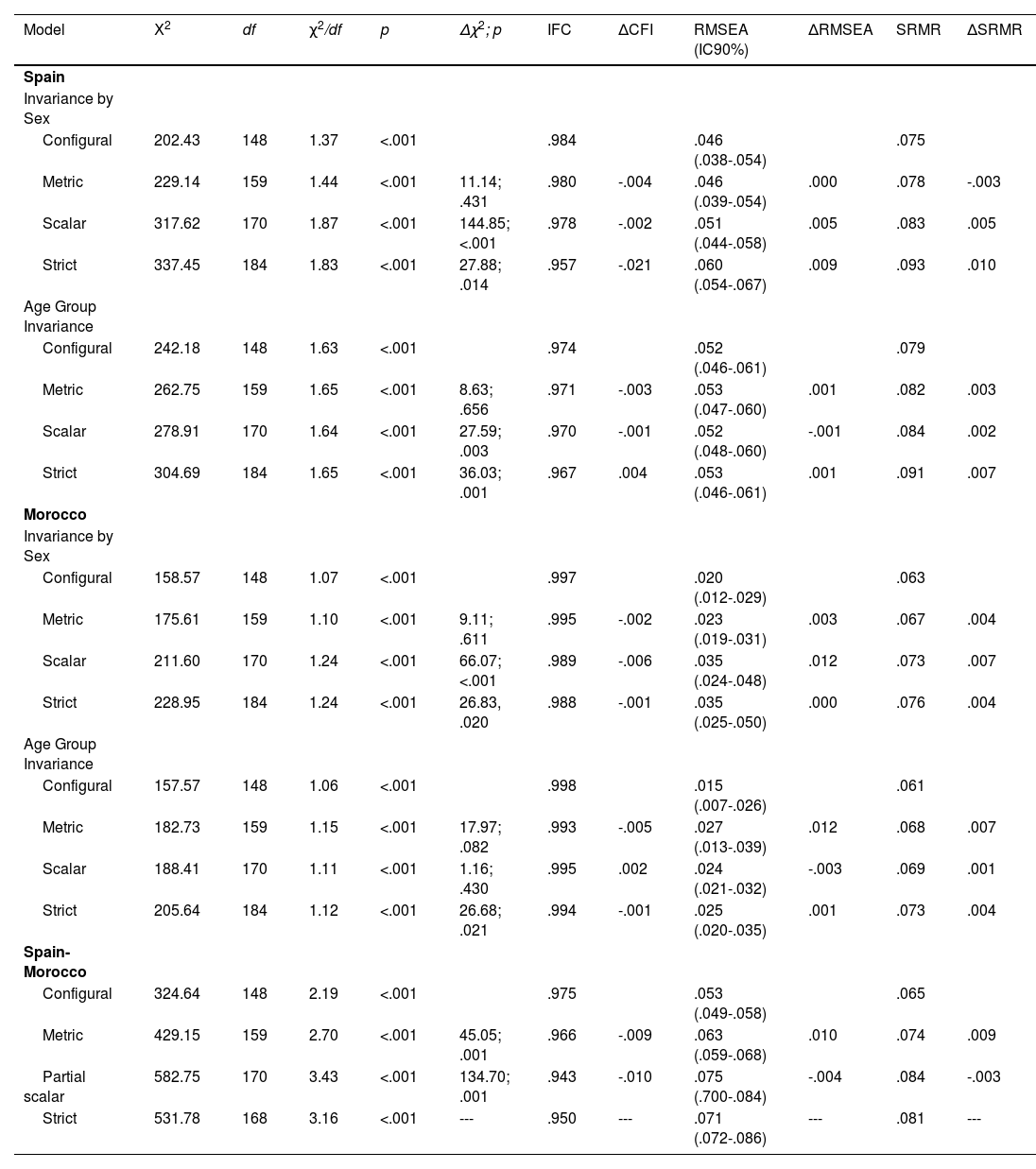

Regarding subgroup differences, the analysis began with the preliminary study of stepwise invariance, with scalar invariance being the minimum requirement to compare means (latent and observed). In the case of Spain, the fit indices obtained (Table 4) showed the equivalence of the measurement model across sexes. Adding restrictions to the regression coefficients, the differences between χ2, RMSEA and SRMR indicated the metric invariance of the model, through which we assessed the equivalence of the intercepts’ values. Given these values, we accepted scalar invariance. Then, by adding restrictions to the residuals, we tested strict invariance, which was not met. The analyses according to age bracket showed that the metric, scalar and strict invariance were confirmed. For Morocco, the fit indices indicated the model’s strict equivalence across sexes. We also found strict invariance by age group.

BASC-S3 Factorial invariance fit indices by sex and age within and across countries

| Model | Χ2 | df | χ2/df | p | Δχ2; p | IFC | ΔCFI | RMSEA (IC90%) | ΔRMSEA | SRMR | ΔSRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain | |||||||||||

| Invariance by Sex | |||||||||||

| Configural | 202.43 | 148 | 1.37 | <.001 | .984 | .046 (.038-.054) | .075 | ||||

| Metric | 229.14 | 159 | 1.44 | <.001 | 11.14; .431 | .980 | -.004 | .046 (.039-.054) | .000 | .078 | -.003 |

| Scalar | 317.62 | 170 | 1.87 | <.001 | 144.85; <.001 | .978 | -.002 | .051 (.044-.058) | .005 | .083 | .005 |

| Strict | 337.45 | 184 | 1.83 | <.001 | 27.88; .014 | .957 | -.021 | .060 (.054-.067) | .009 | .093 | .010 |

| Age Group Invariance | |||||||||||

| Configural | 242.18 | 148 | 1.63 | <.001 | .974 | .052 (.046-.061) | .079 | ||||

| Metric | 262.75 | 159 | 1.65 | <.001 | 8.63; .656 | .971 | -.003 | .053 (.047-.060) | .001 | .082 | .003 |

| Scalar | 278.91 | 170 | 1.64 | <.001 | 27.59; .003 | .970 | -.001 | .052 (.048-.060) | -.001 | .084 | .002 |

| Strict | 304.69 | 184 | 1.65 | <.001 | 36.03; .001 | .967 | .004 | .053 (.046-.061) | .001 | .091 | .007 |

| Morocco | |||||||||||

| Invariance by Sex | |||||||||||

| Configural | 158.57 | 148 | 1.07 | <.001 | .997 | .020 (.012-.029) | .063 | ||||

| Metric | 175.61 | 159 | 1.10 | <.001 | 9.11; .611 | .995 | -.002 | .023 (.019-.031) | .003 | .067 | .004 |

| Scalar | 211.60 | 170 | 1.24 | <.001 | 66.07; <.001 | .989 | -.006 | .035 (.024-.048) | .012 | .073 | .007 |

| Strict | 228.95 | 184 | 1.24 | <.001 | 26.83, .020 | .988 | -.001 | .035 (.025-.050) | .000 | .076 | .004 |

| Age Group Invariance | |||||||||||

| Configural | 157.57 | 148 | 1.06 | <.001 | .998 | .015 (.007-.026) | .061 | ||||

| Metric | 182.73 | 159 | 1.15 | <.001 | 17.97; .082 | .993 | -.005 | .027 (.013-.039) | .012 | .068 | .007 |

| Scalar | 188.41 | 170 | 1.11 | <.001 | 1.16; .430 | .995 | .002 | .024 (.021-.032) | -.003 | .069 | .001 |

| Strict | 205.64 | 184 | 1.12 | <.001 | 26.68; .021 | .994 | -.001 | .025 (.020-.035) | .001 | .073 | .004 |

| Spain-Morocco | |||||||||||

| Configural | 324.64 | 148 | 2.19 | <.001 | .975 | .053 (.049-.058) | .065 | ||||

| Metric | 429.15 | 159 | 2.70 | <.001 | 45.05; .001 | .966 | -.009 | .063 (.059-.068) | .010 | .074 | .009 |

| Partial scalar | 582.75 | 170 | 3.43 | <.001 | 134.70; .001 | .943 | -.010 | .075 (.700-.084) | -.004 | .084 | -.003 |

| Strict | 531.78 | 168 | 3.16 | <.001 | --- | .950 | --- | .071 (.072-.086) | --- | .081 | --- |

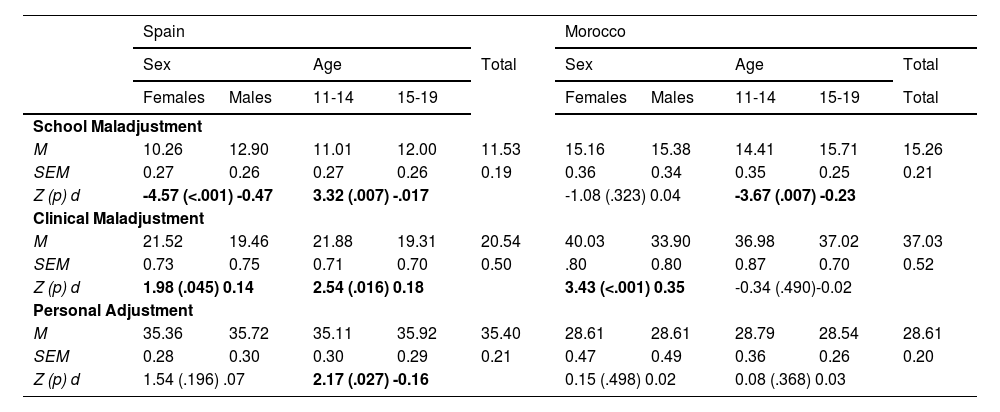

Cross-country invariance analyses yielded fit indices that rejected scalar invariance (Δχ2 = 193.24, p < .001, ΔCFI = -.023, ΔRMSEA = .012, ΔSRMR = .010), but partial scalar invariance was accepted after releasing the intercepts of the sensation-seeking subdimension that did not support this level of restrictions, with factor loadings remaining invariant. These findings indicated that comparisons by sex, age group and countries are feasible (see Table 5).

Latent means in school maladjustment, clinical maladjustment and personal adjustment by sex and age within and across countries

| Spain | Morocco | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Age | Total | Sex | Age | Total | |||||

| Females | Males | 11-14 | 15-19 | Females | Males | 11-14 | 15-19 | Total | ||

| School Maladjustment | ||||||||||

| M | 10.26 | 12.90 | 11.01 | 12.00 | 11.53 | 15.16 | 15.38 | 14.41 | 15.71 | 15.26 |

| SEM | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.21 |

| Z (p) d | -4.57 (<.001) -0.47 | 3.32 (.007) -.017 | -1.08 (.323) 0.04 | -3.67 (.007) -0.23 | ||||||

| Clinical Maladjustment | ||||||||||

| M | 21.52 | 19.46 | 21.88 | 19.31 | 20.54 | 40.03 | 33.90 | 36.98 | 37.02 | 37.03 |

| SEM | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.70 | 0.50 | .80 | 0.80 | 0.87 | 0.70 | 0.52 |

| Z (p) d | 1.98 (.045) 0.14 | 2.54 (.016) 0.18 | 3.43 (<.001) 0.35 | -0.34 (.490)-0.02 | ||||||

| Personal Adjustment | ||||||||||

| M | 35.36 | 35.72 | 35.11 | 35.92 | 35.40 | 28.61 | 28.61 | 28.79 | 28.54 | 28.61 |

| SEM | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.21 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.36 | 0.26 | 0.20 |

| Z (p) d | 1.54 (.196) .07 | 2.17 (.027) -0.16 | 0.15 (.498) 0.02 | 0.08 (.368) 0.03 | ||||||

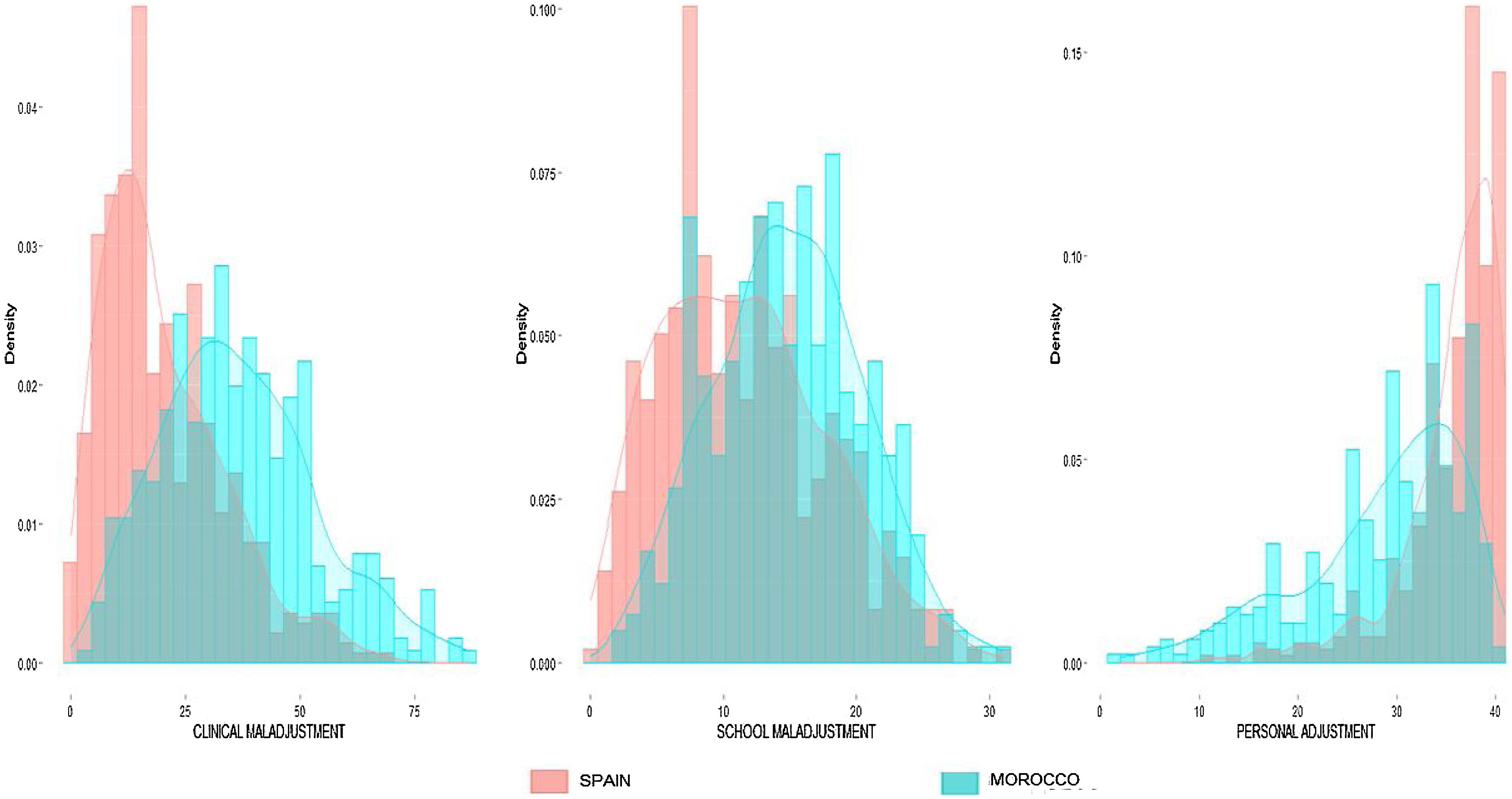

It should be noted that the subdimension sensatio-seeking was retained to calculate the latent mean in the school maladjustment factor because this variable did not significantly affect the overall interpretation of the construct, and the rest of the subdimensions offered a sufficient level of invariance to make valid comparisons across countries. In Spain, statistically significant sex differences were found, but with low effect sizes for school maladjustment and very low for clinical maladjustment. No significant sex differences were found in personal adjustment. When considering age range, significant differences were found for school maladjustment, clinical maladjustment and personal adjustment but with very low effect sizes. In Morocco, something similar occurred; sex differences were detected but with a low effect size in clinical maladjustment, and no differences were detected in school maladjustment or personal adjustment. There were also no significant age group differences in clinical maladjustment or personal adjustment, but there were significant differences in school maladjustment, although also with a low effect size. As shown in Table 5 and Figure 2, the cross-country comparison showed higher scores in Morocco than in Spain in school maladjustment (ΔM = -3.73, ΔSEM = 0.12, Z = -10.89, p < .001, d = -0.66), clinical maladjustment (ΔM = -16.49, ΔSEM = 0.11, Z = -19.55, p < .001, d = -1.04) and lower on personal adjustment (ΔM = 6.79, ΔSEM = 0.08, Z = 19.62, p < .001, d = -1.09) with effect sizes associated with very high differences.

DiscussionThe first step for an adequate intervention is to ensure correct assessment using culturally and linguistically adapted instruments with good metric properties. This study has provided evidence of the suitability of the BASC-S3 for its application in Spain and Morocco. Specifically, the results showed that the questionnaire’s behaviour was similar to that found in the original version (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 1992), with an optimal fit to the model of three related global dimensions and high internal consistency of both dimensions and subdimensions. Although one subdimension in Spain (self-confidence) and two in Morocco (sensation-seeking and self-confidence) showed lower reliability, similar to the Spanish adaptation (González et al., 2004) and the Basque adaptation of the BASC-S2 (Jaureguizar et al., 2012) and BASC-S3 (Bernaras et al., 2017), the first hypothesis proposed in the study was confirmed.

This study provides the Moroccan community with a valid, reliable and culturally appropriate tool for detecting and assessing psychosocial and school adjustment and alleviates the scarcity of validated tools for the adolescent population in this country (El-Ammari et al., 2023). It also increases the cross-cultural projection of the BASC-S3, an instrument that complies with the recommendation to collect direct information from the children themselves (Thapa-Bajgain et al., 2023). Moreover, unlike other instruments, the BASC-S3 offers a balanced perspective of the adolescent's attributes because it considers both negative and adaptive aspects.

Using the BASC-S3 in both Spain and Morocco can help educational institutions identify students who are at risk of academic or personal maladjustment, enabling the implementation of more personalised intervention programmes. In addition, schools can evaluate the effectiveness of their emotional and academic support policies based on the questionnaire. For political and health institutions, it is a valuable tool for collecting large-scale data on adolescent mental health and well-being. This can help design public policies focused on promoting psychological and educational well-being, through specific programmes.

Secondly, we found measurement invariance, by which we assumed the similarity in attributing meanings between sexes, age groups and countries, confirming the second hypothesis. By discarding these biases (Putnick & Bornstein, 2016), we could perform the comparisons needed to achieve the main objective: to know the similarities and differences between Spain and Morocco. Concerning this issue, both in Spain and Morocco, the average scores obtained in the dimensions assessed indicated that adolescents presented adequate adjustment in the school, clinical and personal spheres. As for sex differences, although females obtained higher scores in clinical maladjustment and lower scores in personal adjustment, the magnitude of the differences was small in both countries. In the case of school maladjustment, something similar occurred, as males obtained higher scores, but the effect size associated with the differences was small in both countries. This absence of significant sex differences aligns with the works of Bernaras et al. (2017) and Mancinelli et al. (2021), providing further evidence for the hypothesis of sex similarity advocated by Hyde (2005). As for the differences according to age, in both countries, we only found differences in the scores obtained in early and mid-late adolescence in the case of school maladjustment, but with small effect sizes, in line with the findings of Jaureguizar et al. (2015), results that partially contradict the third hypothesis proposed.

In the comparison of the countries, we found large differences, with higher scores in clinical and school maladjustment and lower scores in personal adjustment in Morocco than in Spain. These differences confirm the fourth hypothesis and point in the direction of the results in the studies by Chahed (2010) with Algerian adolescents and by Petot et al. (2008) with Tunisians. However, these results are not directly comparable, as they were conducted with information reported by parents in the CBCL. Differences between countries could be influenced by a variety of factors, including cultural aspects of conceptions of mental health, and access to medical and psychological care (Gautam et al., 2019). Spain may have a greater public awareness of mental disorders and a more developed medical and socio-educational care system along these lines, with more specific intervention programmes promoting adolescents’ emotional well-being. One of the main measures is the Law for the Comprehensive Protection of Children and Adolescents, passed in 2021, which promotes suicide prevention protocols, specialised training for teachers and the creation of the figure of “well-being coordinator.” These coordinators oversee the implementation of strategies to reduce bullying, improve coexistence and provide emotional support in educational institutions. In addition, roles such as the ‘student helper’, where selected students are trained to identify and support at-risk peers, have been proposed. However, although there are some school-based well-being programmes in Morocco that include collaborate with local and international organisations to promote emotion-regulation skills and reduce school dropout, unlike in Spain, intervention policies are less structured at the national level. However, at the moment, there is a lack of data to support these hypotheses, and they should be treated with caution and tested in future studies.

These results suggest that cultural and contextual factors have a greater impact on school, clinical and personal adjustment than sex or age per se. Future studies should explore this issue, as sex differences involve important social and cultural stereotypes that carry over into clinical and educational practice when, in fact, these differences do not seem to occur equally in all cultural contexts. Knowing the particular characteristics of adolescents in different cultures allows designing more inclusive intervention programmes that consider the specific needs of each group. This is particularly important for migrant adolescents, who often face additional challenges. The Moroccan migrant population is the most numerous in Spanish classrooms. Thus, having a standardised questionnaire to compare the experience of young people in the country of origin and the receiving country can provide key information to create support programmes to promote their social and academic integration and eliminate the language barriers they often encounter in the early stages.

However, it should be noted that the choice of appropriate scales for psychosocial assessment of the migrant population is a crucial aspect that directly influences the accuracy of the assessments and the equity of access to psychological care. If Moroccan scales are used, they can be designed to reflect the cultural norms and behavioural patterns expected within that context. This is beneficial for newly arrived Moroccan adolescents or those who maintain strong cultural ties to their country of origin. Moroccan scales favour a more accurate assessment of the expectations and behaviours of the culture of origin, avoiding the misinterpretation of certain behaviours as dysfunctional when, in fact, they may be normative within their culture. In this case, it would facilitate a more comprehensive assessment, less biased towards the Spanish context.

However, the exclusive use of Moroccan scales may not fully capture the reality of adolescents who were born or raised in Spain and who are exposed to a process of acculturation. In these cases, the cultural experiences of Moroccan youth in Spain are likely to differ significantly from those of their counterparts in Morocco, making scales based on the Moroccan population less accurate in assessing their psychosocial adjustment in a multicultural context such as Spain. Given that the Moroccan school population in Spain is heterogeneous (foreign population, nationalised or with Spanish nationality), one solution could be to develop mixed or adapted scales. These would include a sample made up of both native Spanish adolescents and adolescents of Moroccan and other cultural backgrounds, thus reflecting the cultural diversity of the school context. This would allow for a more accurate and useful assessment for each subgroup of students, adapted to their socio-cultural reality, integrating the nuances of acculturation and the integration process in the country. However, such mixed scales do not exist at present, so it would be advisable to continue working in this direction.

LimitationsThe main limitation was the possible lack of representativeness of the sample due to incidental sampling, which compromised the generalisability of the results. Moreover, in Morocco, only private schools were included because the inclusion of public schools attended by students from rural areas and low socio-economic backgrounds would have precluded the comparison between countries due to the important academic and educational differences present in these social strata in Morocco. There is a high percentage of illiteracy, school drop-out rates, difficulties in accessing academic resources, etc. in Morocco, which are not so frequent in Spain. An additional issue to bear in mind is the possible differences between the samples in other aspects that may be important and were not measured (age and educational level of parents, employment status, etc.). Moreover, the Self-Confidence scale in Spain and the Sensation-Seeking and Self-Confidence scales in Morocco should be studied in more detail, given their lower consistency and the lack of scalar invariance between countries in the Sensation-Seeking subdimension. The fit of the factor models was not investigated either in adolescents from the clinical population diagnosed with any of the most prevalent disorders in this stage— as defined in the DSM-5—or in Moroccan adolescents residing in Spain in order to compare the three groups, which could be very interesting.

ConclusionsPromoting psychosocial and educational adjustment during adolescence requires a multidisciplinary approach that integrates research, clinical intervention, education and social action, with the aim of generating knowledge and promoting positive change in the two cultural contexts under study (Spain and Marocco). Although psychological problems during adolescence are universal, the differences found in this study alert us to the need to consider each culture's idiosyncrasies to develop more specific assessment and intervention tools to increase their effectiveness (Casares et al., 2024). Furthermore, exchanging knowledge between different cultures can enrich existing practices and open new avenues to address challenges in promoting young people's mental health. Finally, accurate, objective and replicable assessment not only has advantages in clinical or educational practice, but is also essential for successful research. Understanding, synthesising and interpreting research findings in diverse populations is only possible if existing assessment instruments can be used reliably and validly across multiple cultural and ethnic groups. The scarcity of such instruments has limited cross-cultural studies, particularly, the contribution of psychoeducational research with Arab children and adolescents to the international research community.