The objective of this study has been to discover the mediating and moderating effect of peer support, family support and teacher support in the relationship between emotional intelligence and suicidal ideation in adolescents. For this purpose, a total of 898 adolescents have participated (MAge = 13.55, SD = 1.66) responding to the WLEIS Scale, the Perceived Social Support Scale, the adaptation of the School Climate Scale, and the Suicide Risk Inventory. The results indicate how: (1) teacher support and family support mediate the relationship between emotional intelligence and suicidal ideation; (2) regardless of gender and age, family support moderates the relationship between emotional intelligence and suicidal ideation, with emotional intelligence helping to reduce suicidal ideation only when there is medium or high family support; (3) peer support and age moderate the relationship between emotional intelligence and suicidal ideation, with peer support helping emotional intelligence reduce suicidal ideation only with older adolescents. These results showed how, in addition to working emotional intelligence in adolescents, introducing the participation of families in the learning process as far as possible, as well as encouraging quality relationships between peers, could have special effects in reducing one of the main causes of adolescent death, such as suicidal behaviour.

El objetivo del presente estudio ha sido el de conocer el efecto mediador y moderador del apoyo entre iguales, del apoyo familiar y del apoyo docente en la relación entre inteligencia emocional e ideación suicida en adolescentes. Para este fin, han participado un total de 898 adolescentes (MEdad = 13.55, DT = 1.66), quienes han respondido a la Escala WLEIS, a la Escala de Apoyo Social Percibido, a la adaptación de la Escala de Clima Escolar, y al Inventario de Riesgo Suicida. Los resultados señalan cómo: (1) el apoyo docente y el apoyo familiar median la relación entre inteligencia emocional e ideación suicida; (2) independientemente del sexo y la edad, el apoyo familiar modera la relación entre inteligencia emocional e ideación suicida, observando cómo la inteligencia emocional ayuda a reducir la ideación suicida solo cuando existe medio o alto apoyo familiar; (3) el apoyo entre iguales y la edad moderan la relación entre inteligencia emocional e ideación suicida, observando cómo el apoyo entre iguales ayuda a que la inteligencia emocional reduzca la ideación suicida solamente con adolescentes de mayor edad. Estos resultados evidencian como, además de tener que trabajar la inteligencia emocional en adolescentes, en la medida de lo posible, introducir también la participación de las familias en los procesos de aprendizaje, así como fomentar las relaciones de calidad entre iguales podría acarrear especiales efectos para reducir una de las principales causas de muerte adolescente, como es el caso de la conducta suicida.

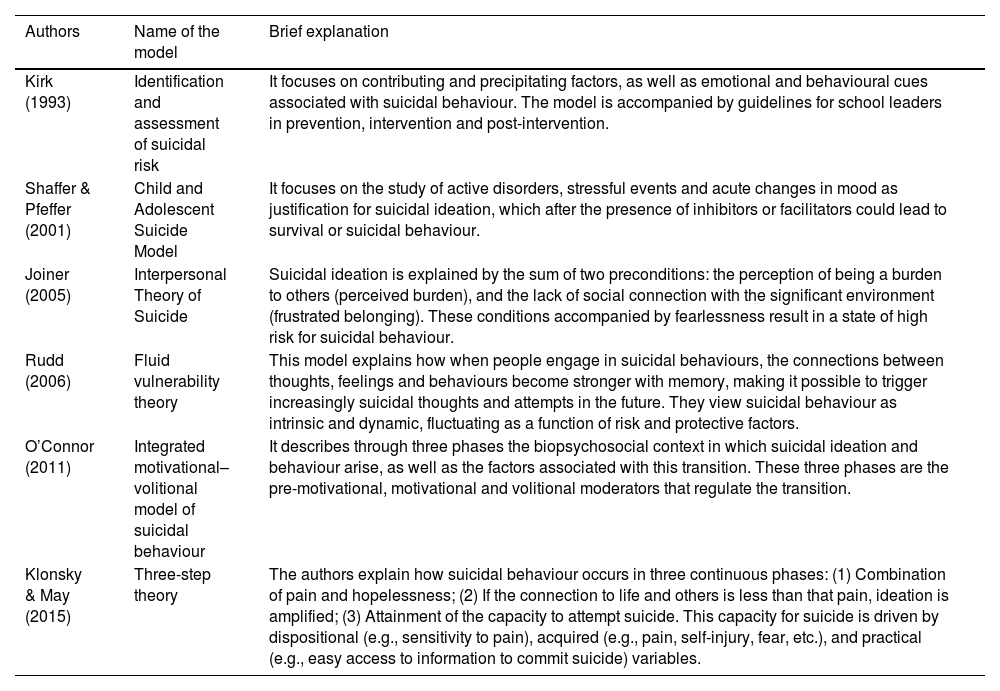

Suicidal behaviour is the third leading cause of death among adolescents worldwide, with 90% of cases occurring in adolescents from countries with low and middle socioeconomic levels (WHO, 2020). In fact, the recent work by Biswas et al. (2020) reveals, with a worldwide sample of almost 300,000 adolescents aged between 12 and 17 years, how the prevalence of adolescent suicidal ideation is 14.0% (95% CI 10.0-17.0%), with Africa being the continent with the highest adolescent suicidal ideation (21.0%) and Asia the continent with the lowest adolescent suicidal ideation (8.0%). These percentages are slightly reduced when talking about adolescent suicidal behaviour in the past year, placing the prevalence of this event at 4.5% (95% CI 3.4-5.9%) (Lim et al., 2019). In view of these developments, suicidal ideation and behaviour in adolescents have become a public concern that is requiring extensive effort to know how and when to prevent it (Hinduja & Patchin, 2018). Therefore, for decades there have been several psychological models that have tried to explain suicidal behaviour (Fonseca et al., 2022). Some of the main models are listed in Chart 1.

Main theoretical models of suicidal ideation and behaviour

| Authors | Name of the model | Brief explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Kirk (1993) | Identification and assessment of suicidal risk | It focuses on contributing and precipitating factors, as well as emotional and behavioural cues associated with suicidal behaviour. The model is accompanied by guidelines for school leaders in prevention, intervention and post-intervention. |

| Shaffer & Pfeffer (2001) | Child and Adolescent Suicide Model | It focuses on the study of active disorders, stressful events and acute changes in mood as justification for suicidal ideation, which after the presence of inhibitors or facilitators could lead to survival or suicidal behaviour. |

| Joiner (2005) | Interpersonal Theory of Suicide | Suicidal ideation is explained by the sum of two preconditions: the perception of being a burden to others (perceived burden), and the lack of social connection with the significant environment (frustrated belonging). These conditions accompanied by fearlessness result in a state of high risk for suicidal behaviour. |

| Rudd (2006) | Fluid vulnerability theory | This model explains how when people engage in suicidal behaviours, the connections between thoughts, feelings and behaviours become stronger with memory, making it possible to trigger increasingly suicidal thoughts and attempts in the future. They view suicidal behaviour as intrinsic and dynamic, fluctuating as a function of risk and protective factors. |

| O’Connor (2011) | Integrated motivational–volitional model of suicidal behaviour | It describes through three phases the biopsychosocial context in which suicidal ideation and behaviour arise, as well as the factors associated with this transition. These three phases are the pre-motivational, motivational and volitional moderators that regulate the transition. |

| Klonsky & May (2015) | Three-step theory | The authors explain how suicidal behaviour occurs in three continuous phases: (1) Combination of pain and hopelessness; (2) If the connection to life and others is less than that pain, ideation is amplified; (3) Attainment of the capacity to attempt suicide. This capacity for suicide is driven by dispositional (e.g., sensitivity to pain), acquired (e.g., pain, self-injury, fear, etc.), and practical (e.g., easy access to information to commit suicide) variables. |

As can be seen from these models, several of them link suicidal behaviour to emotional aspects. In fact, during adolescence, when there is a state of emotional exhaustion in which countless difficulties are perceived, suicidal behaviour may present itself as a way to cope with this situation (Spirito & Esposito-Smythers, 2006). It is worth mentioning how during adolescence intensified emotions and mood swings become frequent (Dawes et al., 2008). When such drastic swings occur, some authors allude to how coping with negative emotions to avoid suicidal attempts becomes essential (e.g., Dawes et al., 2008).

In the vast majority of cases, suicidal behaviour is understood as the end of a chronic problem that can have a variety of causes, although one of the main risk factors is the presence of a shocking and negative event for the adolescent, such as a breakup with a partner, a crisis, the experience of being bullied at school, or the death of a family member, among others (Galindo-Domínguez & Losada, 2023; Valois et al., 2015). Along with this risk factor, the use of drugs and/or alcohol can increase the risk of suicidal behaviour by causing disinhibition in parts of the brain related to judgment and impulse control (Dawes et al., 2008; Valois et al., 2015), as well as having access to firearms or bladed weapons can also increase the risk of suicidal behaviour due to the effectiveness of these tools to cause death (Bridge et al., 2010; Glenn et al., 2020). Recent studies (e.g. Biswas et al., 2020; Glenn et al., 2020) even report new risk factors for suicidal behaviour, such as being female, being an older adolescent, having a low socioeconomic status or having no close friends.

In order to seek avenues for its solution, one of the protective factors against suicidal ideation and behaviour in adolescents that has aroused greater interest in the literature in recent years is that of emotional intelligence (Bonet et al., 2020; Domínguez-García & Fernández-Berrocal, 2018; Galindo-Domínguez & Losada, 2023; Quintana-Orts et al., 2019; Rey et al., 2019), with a statistically significant association observed between low emotional intelligence and high suicidal ideation in adolescents (e.g., Galindo-Domínguez & Losada, 2023).

Understanding what is meant by emotional intelligence is not easy because this construct can vary depending on the theoretical model used as a reference, being the main models to understand the emotional intelligence the mixed models and the ability models. Regarding the mixed models, these understand emotional intelligence from a broad approach, as a series of constant personality traits, socioemotional competencies, motivational perspectives and cognitive skills (Bar-On, 1997; Goleman, 1995), while the ability models understand emotional intelligence only as the ability to process information obtained from emotions (Mayer et al., 2008). Thus, emotionally intelligent people are characterized by understanding the causes of their emotions, in order to subsequently apply regulatory strategies that manage these emotional states (Mayer et al., 2000). For the fieldwork of this study, emotional intelligence will be understood from the ability model, since it will allow us to know how adolescents are able to identify and manage their emotions.

The role of social support in the relationship between emotional intelligence and constructs related to well-beingSocial support refers to the quantity and quality of social networks a person has in his or her life; that is, the relationships and connections he or she has with other people. This support can include love and affection from family and close friends, membership in groups and communities, and participation in social activities. Social support can be an important protective factor against suicidal behaviour and other forms of emotional and psychological distress (Agbaria & Bdier, 2020).

Some recent studies have found that emotional intelligence predicts the social support of significant others, family and friends in a significant sample of adolescents, with the explanatory effect being greater in girls than in boys, and in middle-aged adolescents than in young adolescents (Jiménez et al., 2020). This could be explained by the fact that adolescents able to identify, evaluate and manage their emotions and those of others may be able to generate richer social interactions, thanks to active listening, empathy, respect and mutual help. Consequently, these conditions would be optimal for developing greater positive affect and less negative affect, as well as for developing to a greater degree their life satisfaction and subjective happiness (Hidalgo-Fuentes et al., 2022; Kong et al., 2019).

First, it is observed from the current literature that important efforts have been made for understanding the mediating role of social support in the relationship between emotional intelligence and adolescent well-being. In this line, Zhao et al. (2020) hypothesize how emotional intelligence in adolescents can help to generate better social support to face personal challenges. This hypothesis is supported in their study by demonstrating how resilience, social support, and prosocial behaviours mediate the relationship between emotional intelligence and positive (happiness, fun, being energetic, etc.) and negative (sadness, fear, anxiety, etc.) affect. Similar findings are found by Shuo et al. (2022), who reveal how emotional intelligence helps adolescents perceive greater social support. This, in turn, makes them psychologically more resilient, and thanks to these two conditions, they ultimately develop better well-being. These findings can be explained in that a series of personal characteristics (self-efficacy, self-esteem, etc.) and social characteristics (social support, social climate, etc.) can contribute to building a better predisposition to perceive problems with greater optimism, and in turn, this phenomenon becomes a condition for developing better well-being and mitigating the negative effects associated with personal and academic events (Galindo-Domínguez et al., 2020). Similarly, He et al. (2020) reveal how perceived social support partially mediated between emotional intelligence and mental health in undergraduate students. In this line, it should also take into consideration the works of Aldrich (2017) and Mérida-López et al. (2018) who expose that the development of emotional skills could help to increase perceived social support, and in turn, this help to reduce existing barriers in help-seeking behaviours in adolescents. Likewise, López-Zafra et al. (2019) demonstrate how social support and life satisfaction act as mediators in the relationship between emotional intelligence and depression.

Although most of the works discussed above justify the mediation model tested in the present study, it should be highlighted that other studies reverse the order of the variables and obtain statistically significant results. This is the case of works such as that of Zhao et al. (2019), who observe in university students how a greater amount of childhood trauma leads to a lower amount of perceived social support, and in turn, this lack of social support hinders the development of the different dimensions of emotional intelligence. Finally, this lack of emotional intelligence leads to the development of various psychopathological symptoms (e.g., somatization, anxiety or paranoia).

Second, in the current literature, there is some evidence that studies the moderating effect of certain constructs in the relationship between emotions and mental health. For example, Sharaf et al. (2009) demonstrate how social support moderates the relationship between self-esteem and suicidal risk. Specifically, these authors observe how self-esteem is increasingly effective in reducing suicidal ideation when social support is high. Likewise, Wang et al. (2011) conclude that self-esteem and emotional adjustment moderate the relationship between levels of depressive stress and suicidal ideation in adolescents. Finally, Extremera et al. (2019a) observed in a sample of teachers how peer support moderates the relationship between emotional intelligence and job satisfaction so that, at medium or low levels of social support, having low emotional intelligence is associated with lower scores in engagement, compared to those with high emotional intelligence.

Purpose of the studyFollowing the previous literature review, it is possible to observe certain evidence on how social support could serve as a mediator and moderator of the relationship between emotional intelligence and constructs that directly affect personal well-being. However, previous works such as Mosqueiro et al. (2015) or Suárez et al. (2016) indicate how, despite the existence of literature that supports the impact of emotional intelligence on adolescent well-being, there are few studies that analyse the influence that certain constructs, such as resilience, social support, self-esteem, or coping style, among others, could have on this relationship. Similarly, López-Zafra et al. (2019) add that despite knowing that emotional intelligence shows a statistically significant relationship with a number of dependent variables that affect mental health, such as subjective well-being (e.g. Sánchez-Álvarez et al., 2016), or burnout (e.g. Fiorilli et al., 2019), there is still a lack of knowledge about the intermediate mechanisms of this relationship. Finally, as a limitation of the studies reviewed, it should be emphasized that the vast majority of studies that perform mediation and moderation analyses considering suicidal ideation or behaviour as a dependent variable are scarce. For this reason, the main objectives (O) of this work are the following: (O1) To analyse the mediating effect of social support on the relationship between emotional intelligence and suicidal ideation in adolescents; and (O2) To analyse the moderating effect of social support on the relationship between emotional intelligence and suicidal ideation in adolescents.

For this purpose, the starting hypotheses (H) are: (H1) All types of social support statistically significantly mediate the relationship between emotional intelligence and suicidal ideation in adolescents; and (H2) All types of social support statistically significantly moderate the relationship between emotional intelligence and suicidal ideation in adolescents.

MethodParticipantsThe present study involved a total of 898 Spanish adolescents (MAge = 13.55, SD = 1.26) from 13 schools located in the provinces of Guipúzcoa and Álava (Basque Country, Spain). Of the total, 188 (20.9%) came from public schools and 710 (79.1%) from subsidized schools. This apparent imbalance, in part, can be justified when considering that almost 60% of the centres in this autonomous community are subsidized. Furthermore, of the total sample, 448 participants (49.9%) were boys and 450 (50.1%) girls. In terms of grade, the sample is divided into 195 students (21.7%) in the 1 st year of Secondary Education, 275 (30.6%) in the 2nd year of Secondary Education, 216 (24.1%) in the 3rd year of Secondary Education and 212 (23.6%) in the 4th year of Secondary Education. Likewise, 764 (85.0%) of them have never repeated a grade in Primary or Secondary Education, while 134 (15.0%) of them have.

The study was initiated by contacting all the secondary schools in Guipúzcoa (112 schools) and all the secondary schools in Álava (20 schools) through their main e-mail addresses. These two provinces have been selected because the researchers of this study work in them, making it easier to be close to the centres in person if necessary. A total of 38 secondary education classrooms from a total of 13 schools participated (acceptance rate of 9.8%)

As discussed, schools were selected by non-probability methods. As the data of Coppock et al. (2018) show, after replicating 27 studies originally conducted with nationally representative samples through convenience sampling, there is a high association in the results between both types of sampling, stating that it could be equally valid for research to use this type of sampling.

InstrumentsFirst, information was requested on a series of personal and sociodemographic questions, such as sex, age, grade, and whether or not the student had repeated a grade. Next, to measure emotional intelligence, we used the Spanish adaptation of the WLEIS Scale (Extremera et al., 2019b). Despite the existence of a variety of instruments to measure emotional intelligence depending on the theoretical conceptualization of the construct (as a mixed model or as an ability model), one of the most widely used scales in the academic field is the WLEIS Scale. In addition to its international support, it is a scale that is easy to administer as it is a scale with a small number of items. Specifically, it consists of 16 7-point Likert-type items (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree), divided into four dimensions: self-emotion appraisal (e.g., "I have a good sense of why I have certain feelings most of the time"), other’s emotion appraisal (e.g., "I am a good observer of others’ emotions"), use of emotion (e.g., "I would always encourage myself to try my best"), and regulation of emotion (e.g., "I can always calm down quickly when I am very angry"). Although the scale validated by Extremera et al. (2019b) is used in a 7-point range, for the present work it has been transformed into a 5-point Likert-type scale to unify with all other scales. This change could facilitate student responses by not having to change the graduation of their answers. Likewise, previous works that have used this same scale in 5-point Likert type have demonstrated a validity and internal consistency estimated through Cronbach's α equally optimal as in 7-point Likert scales (e.g., Merino et al., 2016). The validation of this scale, following Extremera et al. (2019b) shows an internal consistency of between α = .79 and .84 for the different dimensions, and goodness-of-fit indices of: χ2 = 610.3, NNFI (Non-Normed Fit Index) = .947, CFI (Comparative Fit Index) = .954, RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) = .068; these values being acceptable for research, given the conditions of α > .70, CFI > .90, and RMSEA < .08 (Galindo-Domínguez, 2020). Although the Extremera et al. (2019b) scale is validated in adult population, from previous studies it is known that the 16 items of the WLEIS also show optimal psychometric properties in Spanish- and English-speaking adolescent population (e.g., Di et al., 2022; Ríos, 2019).

Next, two different instruments were used to measure social support. First, the Perceived Social Support Scale (Arechabala & Miranda, 2002) was used, consisting of 12 items measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree to 5 = totally agree) divided into 2 dimensions: family support (e.g., My family gives me the help and emotional support I need) and peer support (e.g., "I am sure that my friends try to help me"). The validation of this scale, following these authors, shows an internal consistency of between α = .84 and .85 for the different dimensions, and goodness-of-fit indices of: χ2 = 7.6, p < .01, GFI (Goodness of Fit Index) = .850, CFI = .904; these values being optimal for research, given the conditions of α > .70, CFI > .90 (Galindo-Domínguez, 2020). Second, to measure teacher support, the dimension called interpersonal context was used, extracted from the Spanish adaptation of the School Climate Scale (Villa, 1992). This dimension is made up of 4 items measured on a 5-point Likert scale (e.g., My teacher dedicates a lot of time to helping us in our school work and in our personal problems) and in previous works shows an excellent internal consistency of α = .908 (e.g., Cornejo & Redondo, 2001), this value being suitable for research (Galindo-Domínguez, 2020). The Perceived Social Support Scale (Arechabala & Miranda, 2002) was used as it accurately captures the construct to be measured, although only from the point of view of family and friends. For this reason, data collection was complemented with the interpersonal context dimension, taken from the School Climate Scale (Villa, 1992), since this provides relevant information on the support perceived by teachers, in addition to having good psychometric properties.

Finally, to measure suicidal ideation it was used the suicidal ideation dimension (e.g., I have wished to be dead), consisting of 8 items measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) within the Suicide Risk Inventory (Hernández-Cervantes & Gómez-Maqueo, 2006). Following these authors, the internal consistency for the dimension is excellent (α = .900). Although the authors of the scale do not yield statistics assessing goodness of fit, the factor loadings of the items of this dimension range between λ = .366 and .812, and assessing criterion validity, the dimension correlates statistically significantly and inversely with family (r = −.24, p < .01) and personal well-being (r = −.23, p < .01) as well as positively with failure (r = .20, p < .01) and behavioural problems (r = .16, p < .05). This has made this dimension useful and appropriate for measuring suicidal ideation in the adolescent population.

ProcedureThe procedure was initiated by preparing a database of potential participating schools. All schools in the provinces of Guipúzcoa and Álava (Basque Country, Spain) were selected due to their proximity to the researchers. After preparing the database, the management teams were contacted by email and those interested in participating were provided with all the documentation needed to decide whether or not to participate. Specifically, they were asked to read carefully and sign a document that includes the objective of the study, data treatment, and ethical considerations of voluntariness, anonymity and privacy in participation, as well as informed consent for the families. Once the participating centres had agreed, a period of two months was opened to manage the informed consents with the families and to answer the questionnaires. During this period, the students answered the different scales by telematics means during school hours during tutoring time, after being succinctly informed about the purpose of the questions and about the conditions of anonymity and confidentiality of the data, as well as about their voluntary participation in the process and their ability to withdraw when they consider it necessary. These conditions have made it possible to respect all the ethical principles of research of these characteristics. The error in the administration of the tests was corrected by providing the teachers with a document containing precise instructions for informing the students. In this way, in part, it was possible to control potential biases in the application of the test, such as the Hawthorne effect. The anonymity of the answers has been ensured by avoiding asking for personally identifiable information, such as the National Identity Number. In addition, the confidentiality of the data has been maintained by storing and processing them in an exclusive database with access only by the authors of the study.

Finally, each centre has been provided with a personalized report with the general results of both its own school and the total sample, explaining the most significant findings, as well as future guidelines for action based on scientific evidence, based on the results obtained in each school.

Data analysisInitially, a series of preliminary analyses were carried out to obtain a better view of the data used in the main objectives of the study. Specifically, a descriptive analysis was carried out with arithmetic means and standard deviations, correlational analysis with Pearson's r index, and reliability analysis with Cronbach's α and McDonald's ω indices, using SPSS Statistics 24 software. This first phase concluded by studying the goodness of fit of the theoretical model, through the χ2/df, CFI, RMSEA, SRMR (Standardized Root Mean squared Residual) and AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) indices in SPSS AMOS 24 software. Secondly, in order to respond to main objective 1, a mediation analysis was carried out using the Process macro, embedded in SPSS Statistics 24, and the direct, indirect and total effects of the proposed model were analysed. In this analysis, emotional intelligence was considered as an independent variable, the different types of social support as mediating variables, and suicidal ideation as a dependent variable. Finally, in order to respond to main objective 2, a moderation analysis was also carried out through Process. In this analysis, the interactions of the independent variables and the moderating variables were studied, as well as their respective conditional effects. The analysis was carried out considering emotional intelligence as the independent variable, the different types of social support, age and sex as moderating variables, and suicidal ideation as the dependent variable.

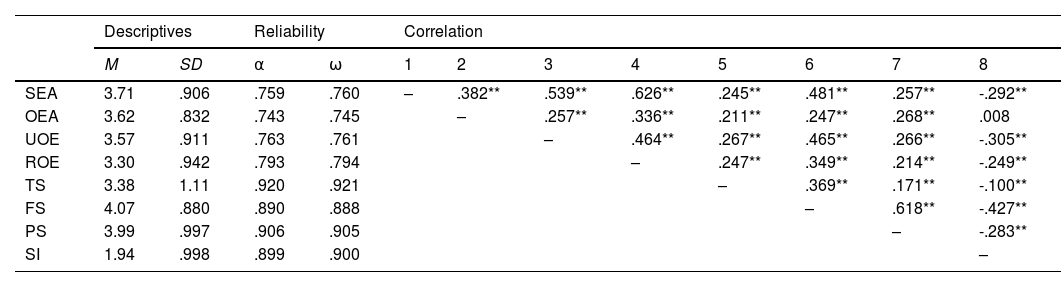

ResultsDescriptive statisticsInitially, in order to get an overview of the data, a descriptive, correlational and reliability study of the main dimensions of emotional intelligence, social support and suicidal ideation was carried out (Table 1). Descriptive analyses show moderate values for the means of the emotional intelligence dimensions, moderate to high values for the means of the social support dimensions, and considerably low values for the mean of the suicidal ideation dimension. Likewise, statistically significant and positive correlations are observed between all dimensions of emotional intelligence and the different types of social support, and statistically significant and negative correlations between all dimensions of social support and suicidal ideation. Statistically significant correlations are also found between all dimensions of emotional intelligence and suicidal ideation, except for the dimension of appraisal of others' emotions. Reliability, calculated through both Cronbach's α and McDonald's ω, yields adequate values for investigations. This analysis is complemented with the calculation of Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values, yielding favourable values for all dimensions: self-emotion appraisal (CR = .848, AVE = .585); other’s emotion appraisal (CR = .842, AVE = .575); use of emotion (CR = .849, AVE = .586); regulation of emotion (CR = .868, AVE = .624); teacher support (CR = .943, AVE = .807); family support (CR = .913, AVE = .569); peer support (CR = .934, AVE = .781); suicidal ideation (CR = .925, AVE = .611). Similarly, the theoretical model yields optimal goodness-of-fit values (χ2/df = .309, CFI = .928, RMSEA = .048, SRMR = .064, AIC = 2496.56).

Descriptive, correlational and reliability analysis of the different dimensions

| Descriptives | Reliability | Correlation | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | α | ω | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| SEA | 3.71 | .906 | .759 | .760 | – | .382** | .539** | .626** | .245** | .481** | .257** | -.292** |

| OEA | 3.62 | .832 | .743 | .745 | – | .257** | .336** | .211** | .247** | .268** | .008 | |

| UOE | 3.57 | .911 | .763 | .761 | – | .464** | .267** | .465** | .266** | -.305** | ||

| ROE | 3.30 | .942 | .793 | .794 | – | .247** | .349** | .214** | -.249** | |||

| TS | 3.38 | 1.11 | .920 | .921 | – | .369** | .171** | -.100** | ||||

| FS | 4.07 | .880 | .890 | .888 | – | .618** | -.427** | |||||

| PS | 3.99 | .997 | .906 | .905 | – | -.283** | ||||||

| SI | 1.94 | .998 | .899 | .900 | – | |||||||

Note. * p < .05. ** p < .01. SEA = Self-emotion appraisal; OEA = Other’s emotion appraisal; UOE = Use of emotion; ROE = Regulation of emotion; TS = Teacher support; FS = Family support; PS = Peer support; SI = Suicidal ideation.

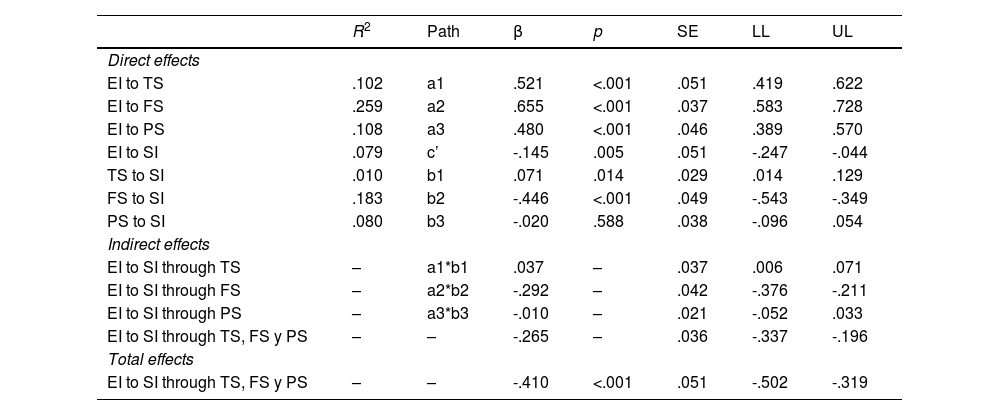

Subsequently, in response to the first main objective of the study, a mediation analysis is carried out, considering emotional intelligence as an independent variable, suicidal ideation as a dependent variable, and teacher support, family support and peer support as mediating variables. The mediation analysis is helpful to know whether emotional intelligence serves to reduce suicidal ideation thanks to social support, which could function as an intermediate piece of this relationship.

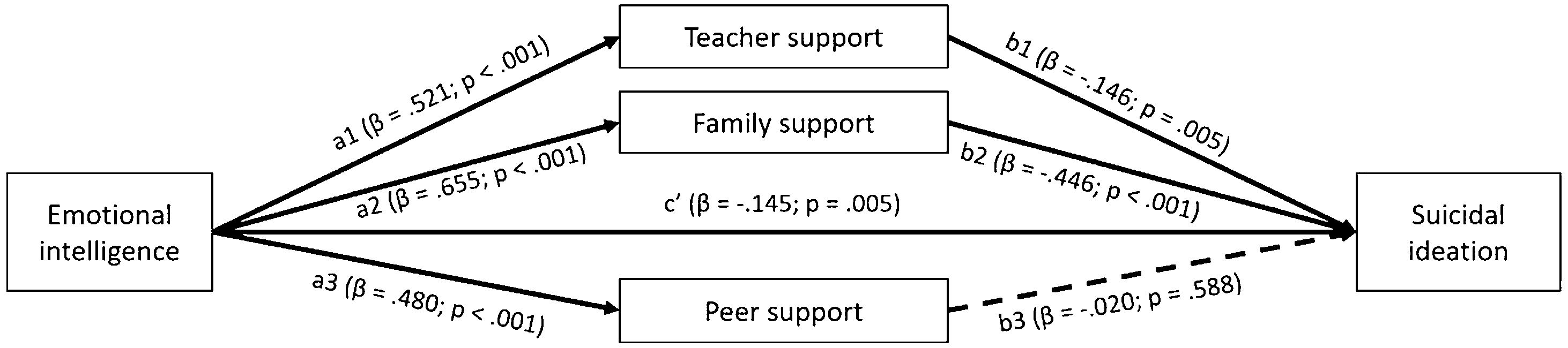

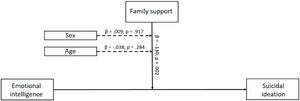

As seen in Figure 1, the direct effects of emotional intelligence towards teacher support (R2 = .102, β = .521, p < .001), family support (R2 = .259, β = .655, p < .001), peer support (R2 = .108, β = .480, p < .001) and suicidal ideation (R2 = .079, β = -.145, p = .005) are statistically significant. This is also the case for the direct effects of teacher support (β = -.146, p = .005) and family support (β = -.466, p < .001) towards suicidal ideation, although this is not the case for peer support, where a statistically non-significant association towards suicidal ideation is observed (β = -.020, p = .588). Of all these direct effects, especially high values are found between emotional intelligence and family support (β = .655, p < .001), as well as from family support towards suicidal ideation (β = -.446, p < .001).

Next, the indirect effects of the mediation model are analysed. These values in Table 2 show that the indirect effects of emotional intelligence towards suicidal ideation via teacher support (β = .037, LI = .006, LS = .071), and via family support (β = -.292, LI = -.376, LS = -.211) are statistically significant in that the value 0 is not included in the interval. This is not the case for the path from emotional intelligence to suicidal ideation via peer support (β = -.010, LI = -.052, LS = .033), which is statistically non-significant in that for the 95% confidence interval the cut-off includes the value 0 in this range (Galindo-Domínguez, 2020).

Results of the mediation analysis

| R2 | Path | β | p | SE | LL | UL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effects | |||||||

| EI to TS | .102 | a1 | .521 | <.001 | .051 | .419 | .622 |

| EI to FS | .259 | a2 | .655 | <.001 | .037 | .583 | .728 |

| EI to PS | .108 | a3 | .480 | <.001 | .046 | .389 | .570 |

| EI to SI | .079 | c’ | -.145 | .005 | .051 | -.247 | -.044 |

| TS to SI | .010 | b1 | .071 | .014 | .029 | .014 | .129 |

| FS to SI | .183 | b2 | -.446 | <.001 | .049 | -.543 | -.349 |

| PS to SI | .080 | b3 | -.020 | .588 | .038 | -.096 | .054 |

| Indirect effects | |||||||

| EI to SI through TS | – | a1*b1 | .037 | – | .037 | .006 | .071 |

| EI to SI through FS | – | a2*b2 | -.292 | – | .042 | -.376 | -.211 |

| EI to SI through PS | – | a3*b3 | -.010 | – | .021 | -.052 | .033 |

| EI to SI through TS, FS y PS | – | – | -.265 | – | .036 | -.337 | -.196 |

| Total effects | |||||||

| EI to SI through TS, FS y PS | – | – | -.410 | <.001 | .051 | -.502 | -.319 |

Note. SE = Standard error; LL = Lower Limit; UP = Upper Limit; EI = Emotional intelligence, TS = Teacher support; FS = Family Support; PS = Peer Support; SI = Suicidal Ideation; Analysis performed with 10,000 bootstrap samples.

These data support the idea that emotional intelligence contributes to reducing suicidal ideation, thanks in part to the fact that emotional intelligence helps adolescents perceive that they are receiving support from teachers and family to a greater degree, making this a necessary condition for significantly reducing suicidal ideation. However, as previously stated in the theoretical review, it is necessary to comment that this model could also be significant and theoretically justifiable if social support were considered as an independent variable and emotional intelligence as a mediating variable. In this sense, the interpretation could indicate that the social support of the people closest to the adolescents, thanks to certain characteristics (their behaviour, personality, etc.), makes them improve their emotional intelligence, and this in turn contributes to reducing distress (Zhao et al., 2019). Even being aware of this interpretation, it is noted that this alternative model is theoretically and statistically supported, but with the data from the present study, the predictive ability of emotional intelligence towards social support is greater than in the case of social support towards emotional intelligence. Similarly, the indirect effect of the chosen model is considerably higher than the alternative model.

Social support moderation analysisFinally, in response to the second main objective of the study, a moderation analysis was carried out, considering emotional intelligence as an independent variable, suicidal ideation as a dependent variable and teacher support, family support and peer support as a moderating variable. The moderation analysis is helpful to find out whether the strength of emotional intelligence towards suicidal ideation varies according to the degree of perceived social support. Initially, when teacher support is introduced as a moderating variable, a statistically non-significant interaction between emotional intelligence and teacher support is observed (β = -.055, p = .151). These results indicate that the impact of emotional intelligence on suicidal ideation, which was found in the previous mediation analysis, remains stable in intensity regardless of the perceived teacher support.

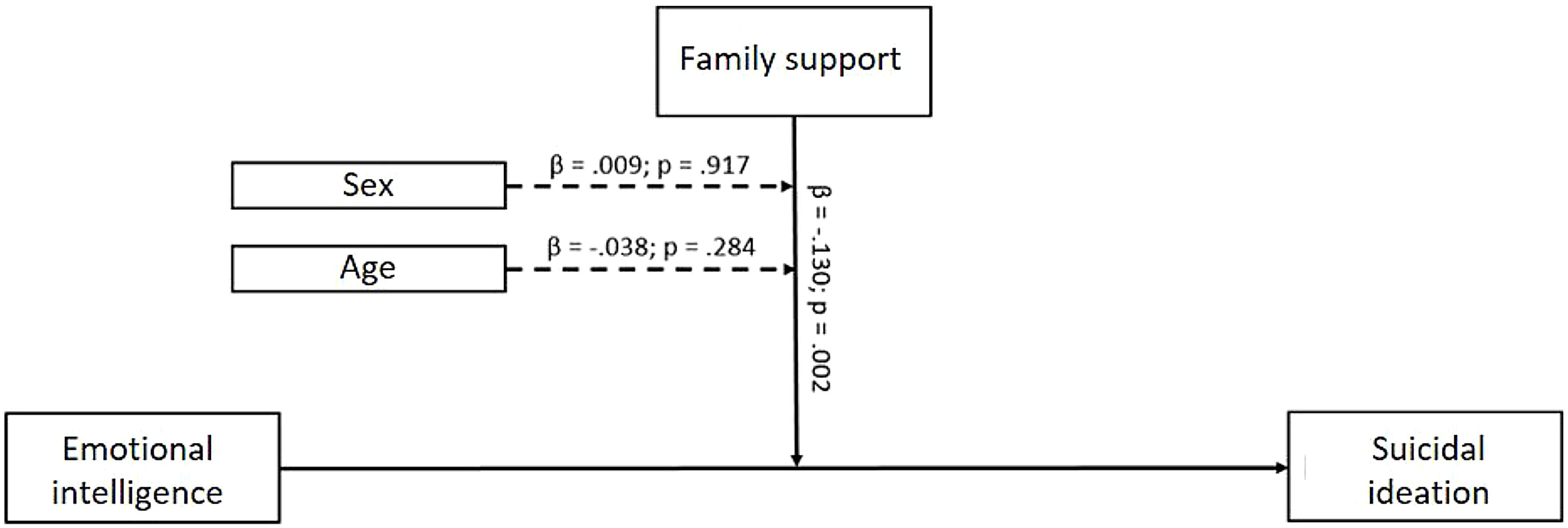

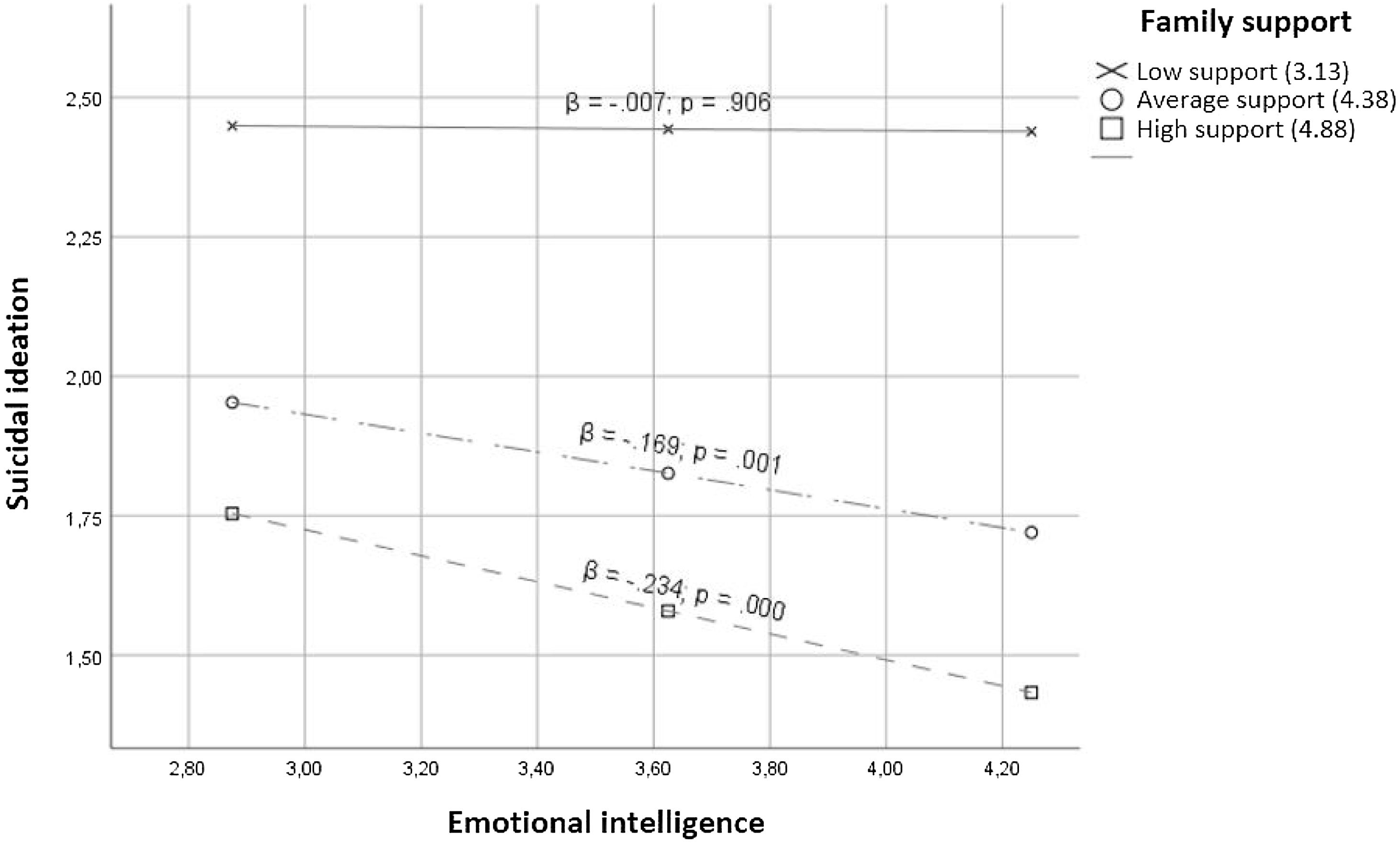

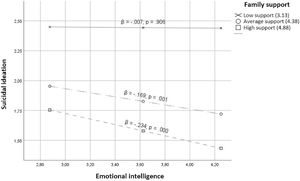

Next, in Figure 2, we observe how, regardless of sex (β = .009, p = .917) and age (β = -.038, p = .284), family support moderates the relationship between emotional intelligence and suicidal ideation (β = -.130, p = .002). In this line, the conditional effects of this analysis yield information on how regardless of the values of emotional intelligence (low, medium or high), when one has low family support, suicidal ideation is not reduced (β = -.007, p = .906, LI = -.131, LS = .116). Furthermore, this analysis reveals how having medium (β = -.169, p = .001, LI = -.272, LS = -.065) or high family support (β = -.234, p < .001, LI = -.354, LS = -.113), having increasingly better emotional intelligence contributes to a more marked reduction in suicidal ideation. This effect can be seen visually in Figure 3.

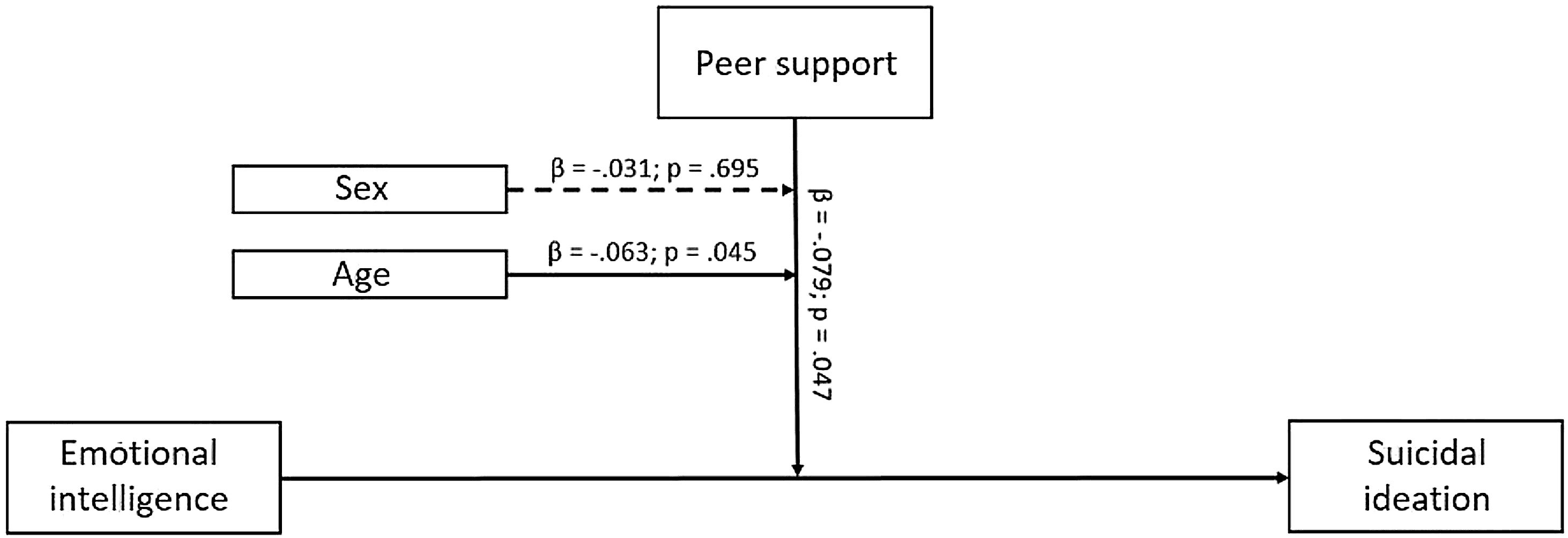

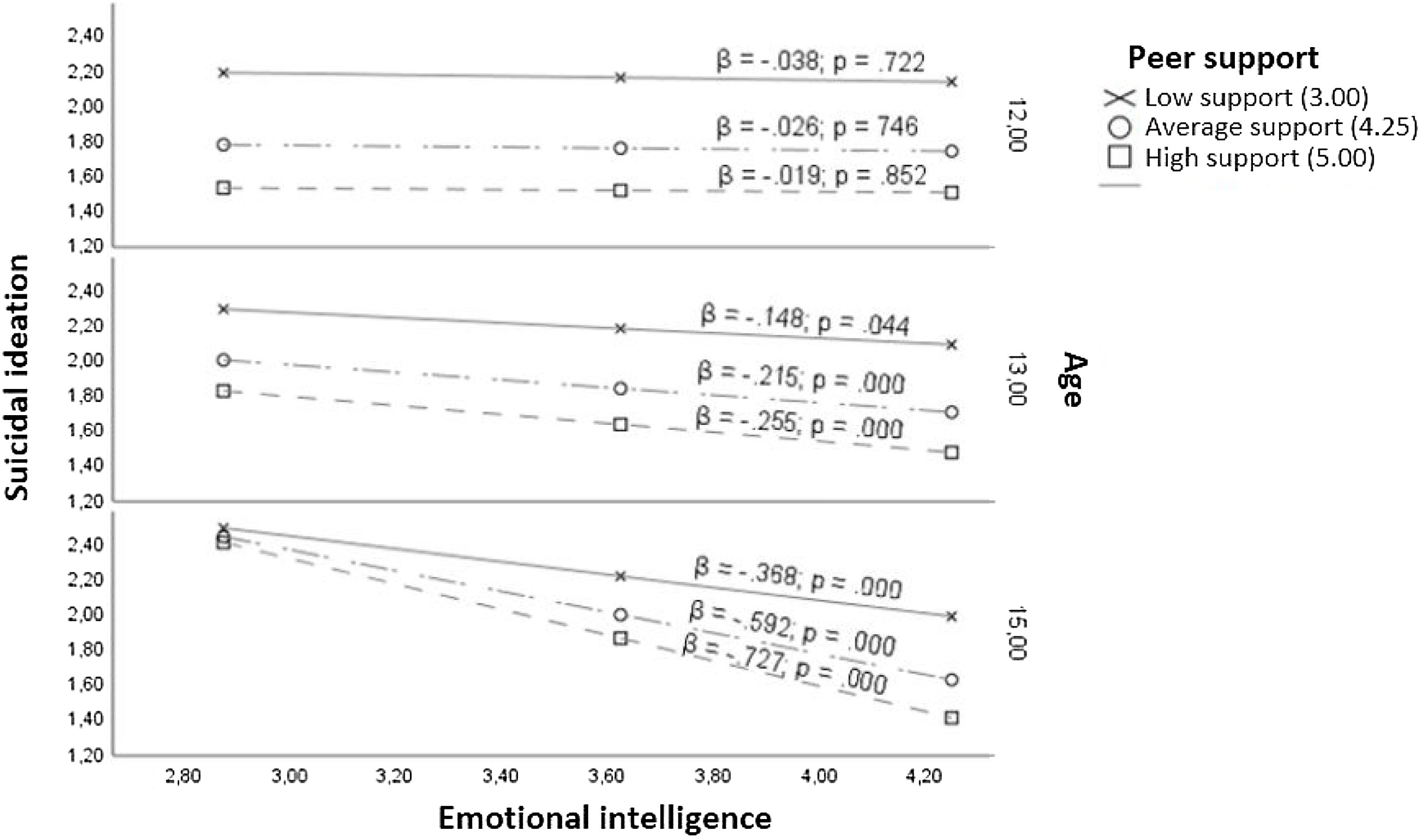

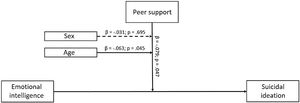

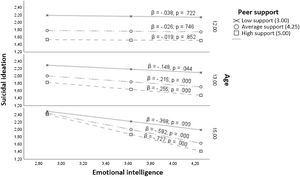

Likewise, as shown in Figure 4, we observe that the interaction between emotional intelligence and peer support is statistically significant (β = -.079, p = .047). Furthermore, using the moderated moderation analysis, we observe that the interaction between age, emotional intelligence and peer support is statistically significant (β = -.063, p = .045), while the introduction of the sex variable causes it not to be statistically significant (β = -.031, p = .695).

Illustrated in Figure 5, and based on the conditional effects of the analysis, it can be seen that emotional intelligence only contributes to reducing suicidal ideation when there is high peer support in middle-aged and older adolescents.

DiscussionThe main objectives of the present study were to find out whether perceived social support mediates and moderates the relationship between emotional intelligence and suicidal ideation. The results leave three interesting findings. The first finding, in line with main objective 1, permits us to partially accept hypothesis 1 by demonstrating how the perceived social support of teachers and families mediates the relationship between emotional intelligence and suicidal ideation. This finding gives rise to two interpretations. First, it shows how students with good emotional intelligence are capable, among other things, of judging the actions and emotions of others more solidly, which contributes to perceiving more accurately the support that teachers and family members are providing through empathy, active listening, respect, encouragement, etc., this being a key factor in reducing suicidal ideation. Second, this finding demonstrates how emotional intelligence can serve as a basis for improving the prosocial behaviour of adolescent students, thus generating higher quality social relationships that contribute to improving their life satisfaction and subjective happiness (Hidalgo-Fuentes et al., 2022; Kong et al., 2019). This finding is complementary to the results of previous studies showing the mediating role of social support in the relationship between emotional intelligence and positive dependent variables, such as well-being (e.g. Shuo et al., 2022), positive mental health (He et al., 2020), positive affect (Zhao et al., 2020) and help-seeking (Aldrich, 2017; Mérida-López et al., 2018), as well as the mediating role of social support in the relationship between emotional intelligence and negative dependent variables such as negative affect (Zhao et al., 2020) or depression (López-Zafra et al., 2019).

The second and third findings, associated with main objective 2, also permit us to partially accept hypothesis 2. Specifically, we observe that, on the one hand, regardless of the age and sex of the adolescent, emotional intelligence is much more effective in reducing suicidal ideation when there are medium or high levels of social support from the family. On the other hand, it is observed that, in younger adolescents, greater peer support does not contribute to a greater degree of emotional intelligence in reducing suicidal ideation, as it does in middle-aged and older adolescents. These two findings are partially related to previous studies revealing how social support functions as a buffer both in the relationship between self-esteem and suicidal risk (Sharaf et al., 2009), and in the relationship between emotional intelligence and enthusiasm for work (Extremera et al., 2019a), or even in findings showing how older adolescents were more prone to suicidal behaviour (Biswas et al., 2020; Glenn et al., 2020). However, the results of this study are considerably novel and useful as there is little literature on the moderating impact of social support on the relationship between emotional intelligence and suicidal ideation. These moderating effects lend strength to the conclusion that emotional intelligence may be considerably more effective in reducing suicidal ideation when there are especially adequate levels of family support, and adequate levels of peer support, especially in older adolescents.

All these findings have a number of interesting theoretical and practical implications that should be discussed. With regard to the theoretical implications, the present analyses contribute to a more solid corpus of studies aimed at analysing protective factors for suicidal ideation in adolescents. Specifically, these findings are of interest to researchers, psychologists, trainers and educators in that they shed light on why suicidal ideation can be reduced through social support (mediation analysis), and what influence social support has when emotional intelligence tries to reduce suicidal ideation (moderation analysis).

With regard to the practical implications, firstly, these results highlight the importance of working on emotional intelligence to reduce suicidal ideation in adolescence, as it is known from previous studies that, through well-designed interventions, it is possible to improve emotional intelligence and reduce suicidal ideation in adolescents (e.g. Mohamed et al., 2017; Mamani et al., 2018). To this end, it is necessary to teach students in education-related degrees in their initial training, as well as in-service teachers in their in-service training, ideas for working on emotional intelligence with their students in the classroom. For this reason, teachers should be aware of the dynamics that allow them to work on emotional intelligence in the classroom and at school, both transversally and specifically in tutoring hours. In this sense, there is a variety of resources that could serve as a reference for working on emotional intelligence with students (e.g., Basses et al., 2021).

Secondly, these results are useful for assessing the essential role of families in the teaching-learning processes, both inside and outside the classroom, when it comes to reducing suicidal ideation. Specifically, Hoover-Dempsey et al. (2005) discuss a number of actions that can be implemented by the school to encourage family involvement, including: (1) Creating an attractive and welcoming school climate (e.g., creating a visual display in the entrance areas and hallways of the school that reflects all families in the school, recruiting families or finding volunteer families who can provide other parents with information about how the school works, translations as needed, celebrations on special days, conferences and trainings for families, or workshops with families, etc.); (2) Empower teachers to improve family involvement (set up regular meetings for discussion on family involvement, analysis of proposals that have been successful at the school, showcasing student projects and performances, providing opportunities to improve two-way communication, providing opportunities for families to collaborate with other families, etc.); and (3) Enable families to participate in the school's activities (e.g., to provide opportunities for parents to share their experiences with other families, etc.). ); and (3) Enabling families to join existing structures to improve participation (setting up after-school programmes to increase school communication with families, using existing groups in the AMPA to invite new families, etc.).

Thirdly, these results may serve to make teachers in general, and Secondary Education teachers in particular, reflect on the significant role they have in reducing suicidal ideation in their students through the development of emotional competences they work with them, as well as through the social support they can provide them with.

Fourthly, these results can be used at the political and institutional level to address suicidal ideation, providing families and teachers with opportunities (e.g., through social events that allow for greater closeness between family-children, or through training programmes for families on how to work on emotions at home and how to provide social support, etc.) and resources (economic, personal, material, etc.) to help their children and students, respectively, to reduce suicidal ideation. In addition, authors such as Turecki et al. (2019) advocate the importance of carrying out preventive interventions against suicidal behaviour in a coordinated manner between psychologists and health and social initiatives.

Finally, these findings are not exempt of limitations that must be taken into account when interpreting the results. The first limitation refers to the characteristics of the sample. More specifically, the fact that this sample comes exclusively from adolescents in the Basque Country. This is why it might be interesting for future studies to replicate the same data analysis applied to students from other parts of Spain, or even from different cultures, in order to compare results. The second limitation refers to the type of cross-sectional research that has been carried out. This limitation is relevant to take into consideration because despite finding a statistically significant model, as has been commented both in the literature review and in the results referring to the mediation analysis, the model that considers social support as an independent variable and emotional intelligence as a mediating variable is also statistically significant. Consequently, in order to clarify which of the two pathways is more relevant in the mediation and moderation analyses, it would be necessary to collect longitudinal data. The third limitation refers to the lack of data on other relevant personal variables, such as socioeconomic status, previous history of emotional problems, or previous history of suicide attempts, as well as data on other complementary scales that could have helped to reduce response bias to a greater degree, such as the social desirability scales. Finally, the fourth limitation refers to the fact that, despite having respected the ethical principles (confidentiality, privacy, informed consent, etc.) for research set out in the Declaration of Helsinki, the present study was not submitted for evaluation to the university's Research Ethics Board.

Despite the limitations explained above, this work hopes to be the beginning of a series of future research that will help to understand the role of social support and the impact of various protective and risk factors in reducing one of the main adolescent problems, such as suicidal ideation and behaviour.

FundingOpen Access funding provided by University of Basque Country.