Psychological distress is an increasing concern among adolescents worldwide. Cybervictimization is considered one of the stressors that adolescents may face, and it significantly impacts various indicators of suicide risk (i.e., symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress, and suicidal ideation). However, teacher emotionally intelligent behaviors (TEIB) might mitigate the links between cybervictimization experiences and suicide risk factors. This study aimed to examine the relationships between cybervictimization and several suicide risk indicators, as well as the potential moderating role of TEIB in these links. A sample of 1,866 (996 girls) adolescents (Mage = 13.99, SD = 1.44) participated in this study and completed widely validated measures. Moderation analyses revealed that TEIB moderated the positive associations between cybervictimization and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress, even after controlling for the effects of sociodemographic factors (i.e., age and gender) and emotional intelligence. However, TEIB did not moderate the link between cybervictimization and suicidal ideation. These novel findings both underscore the significance of students' perceptions of TEIB in shaping their psychological well-being and highlight potential avenues for research aimed at mitigating the consequences of cybervictimization.

El desajuste psicológico constituye una preocupación creciente en la adolescencia a nivel mundial. Se considera que la cibervictimización es uno de los factores estresantes que pueden sufrir los y las adolescentes y que afecta significativamente a varios indicadores de riesgo de suicidio (i.e., síntomas de depresión, ansiedad y estrés e ideación suicida). No obstante, los comportamientos emocionalmente inteligentes docentes (CEID) podrían mitigar los vínculos de las experiencias de cibervictimización y los factores de riesgo de suicidio asociados con estas. Este estudio ha tenido como objetivo examinar las relaciones entre la cibervictimización y varios indicadores de riesgo de suicidio, así como el posible papel moderador de los CEID en estas relaciones. Un total de 1.886 adolescentes (996 chicas; Medad = 13,99; DT = 1,44), participan en este estudio y han completado medidas ampliamente validadas. En los análisis de moderación se ha revelado que los CEID moderan las asociaciones positivas entre la cibervictimización y los síntomas de depresión, ansiedad y estrés, incluso después de controlar el efecto de factores sociodemográficos (i.e., edad y género) y la inteligencia emocional. Sin embargo, los CEID no moderan el vínculo entre la cibervictimización y la ideación suicida. Estos hallazgos novedosos destacan la importancia de la percepción del alumnado sobre los CEID en la formación de su bienestar psicológico y señalan líneas potenciales de investigación orientadas a reducir las consecuencias de la cibervictimización.

Psychological distress is a public health challenge with increasing rates that affect approximately 20% of the children and adolescents worldwide (World Health Organization, 2021). Adolescence is a period characterized by significant physical, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral development changes that encompasses vulnerability for several psychological problems (Rapee et al., 2019). During this period, adolescents are challenged by environmental factors such as social interactions with peers (Rapee et al., 2019), also in the digital realm (Boniel-Nissim et al., 2022). Certain social interactions within this digital realm involve acts of online aggression directed towards peers, often taking place under conditions of anonymity and power imbalances between the aggressor and the victim. This phenomenon of online social aggression is commonly referred to as cyberbullying, with cybervictimized adolescents often struggling to defend themselves effectively (Baldry et al., 2017).

The link between cybervictimization and suicide risk factorsThe theoretical framework posited by Bonner & Rich (1987) indicates that several factors contribute to an increased susceptibility to death by suicide during adolescence. Accordingly, findings from several studies have implicated depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation as significant risk factors associated with suicide in adolescent and adult populations (Chang et al., 2017; Mościcki, 2001). Adolescents who experience cybervictimization tend to report increased symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress, as well as a higher risk of suicidal ideation and thoughts compared to non-victims (Li et al., 2022; Marciano et al., 2020). Given the rising incidence of school bullying and cyberbullying, and their significant association with suicide risk factors (Katsaras et al., 2018; Li et al., 2022), it is crucial to examine potential and specific predictors of suicide risk during adolescence associated with negative experience at school, such as cybervictimization. On this basis, we have examined suicide risk factors as psychological distress symptoms (i.e., symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress), and suicidal ideation among adolescents in the context of cybervictimization.

The protective role of teacher emotional intelligenceAn expanding body of research has delved into the association between cybervictimization and the risk of suicide among adolescents (e.g., Li et al., 2022). However, there remains a scarcity of understanding regarding the specific microsystem factors, particularly those related to teachers, that may modulate this link (Divecha & Brackett, 2020). Applying the Prosocial Classroom Model proposed by Jennings & Greenberg (2009), several dimensions pertaining to teachers’ social and emotional resources may exert an indirect impact on adolescents’ mental health. More specifically, one critical dimension to maintain a classroom where everyone feels safe, connected, and engaged in learning relates to teachers’ emotional intelligence (EI; Divecha & Brackett, 2020). Following the ability EI model, teachers may put into practice their own EI abilities, including appraisal, use, understanding, and regulation of emotions to foster motivational resources among students (Brackett et al., 2019). Moreover, teachers’ EI abilities including empathy both plays a key role in accounting for differences in students’ behavioral difficulties and promotes school connectedness, which eventually affects the onset of health-risk behaviors and engagement in risk behaviors (Aldrup et al., 2022).

Beyond the role of teachers’ EI on cyberaggression, teachers’ emotion regulation is significantly related with adolescents’ emotional distress (Braun et al., 2020). Braun et al. (2020) found that students reported low emotional distress (including depressive and anxiety symptoms) when their teachers tended to use cognitive reappraisal. Finally, a recent study with Australian high school teachers revealed that teachers’ EI was a positive predictor of the seriousness of indirect bullying and self-efficacy. These two variables were found to mediate the effect of teacher EI on the likelihood of intervening in students’ indirect bullying (Shute et al., 2022). However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have explored students’ perceptions of their teachers’ EI abilities. Investigating this aspect constitute a novel approach that could contribute the field, as teachers’ EI is regarded as a crucial resource for the effectiveness of preventive programs aimed at reducing aggressive behaviors (Divecha & Brackett, 2020; Shute et al., 2022).

The moderating role of teacher emotionally intelligent behaviors in the links between cybervictimization and suicide risk factorsIn the present study, we focused on a novel school-related factor, namely, teacher emotionally intelligent behavior (TEIB) as a construct referring to those behaviors involving teachers’ emotional abilities that are perceived by students in school settings. We adapted this construct from work settings considering the salient influence of teachers’ EI on students’ outcomes (Brackett et al., 2019; Jennings et al., 2021). Following the Prosocial Classroom model (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009), teachers with EI are more attentive to students’ needs and, therefore, would reduce the likelihood of students’ classroom misbehavior (Nizielski et al., 2012).

Adolescents perceiving high TEIB may identify their teachers as positive role models who appraise students’ emotions and that understands how their decisions and behaviors affect how others feel at classroom (Jennings et al., 2021; Nizielski et al., 2012). Moreover, students identifying their teachers as EI models may display more reliance on their educators’ competence to deal with interpersonal issues like bullying and cyberbullying (Divecha & Brackett, 2020; Konishi et al., 2010). Thus, TEIB may nurture teacher-student relationship and even have an indirect effect on seeking support and psychological health (Braun et al., 2020; Jennings & Greenberg, 2009). Conversely, adolescents perceiving low TEIB may view their teachers as ineffective at helping students feel better when they are disappointed or upset. Consequently, they may feel hesitant to express their emotions to their teachers, perceiving them as unable to understand the reasons behind certain emotions in the classroom (Zoromski et al., 2021). Although there is evidence regarding the impact of teachers’ responses to classroom disruptive behaviors, the role of TEIB in relation to adolescents’ suicide risk in the context of cybervictimization remains unclear.

As indicated in the Prosocial Classroom Model (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009), it is plausible that adolescents’ perceptions of TEIB may indirectly influence their psychological adjustment in the context of cyberbullying. However, literature in this field is scarce. Available evidence focuses on the perceptions teachers hold regarding their own abilities, thereby lacking relevant data on whether adolescents perceiving high TEIB may benefit from this school-related factor. Given that the levels of TEIB perceived in classrooms may act as critical assets for reducing mental health problems among adolescents (Braun et al., 2020; Jennings & Greenberg, 2009), providing results on the potential moderating role of TEIB may strengthen the persistence and efficacy of anti-bullying programs (Ng et al., 2022). Thus, it seems relevant to explore whether TEIB could act as a school resource that can diminish the link between cybervictimization and suicide risk factors.

Control variables: Sociodemographic and emotional intelligenceThe traditional gender and age variables have undergone extensive examination in cyberbullying contexts. Regarding gender, girls report more often being a cybervictim than boys do (e.g., Baldry et al., 2017), and they suffer more from psychological maladjustment (e.g., Rapee et al., 2019). In relation to age, older adolescents are more at risk for cybervictimization than younger adolescents due possibly to their easier access to technologies (Evangelio et al., 2022; Lozano-Blasco et al., 2023). Prior research has suggested that middle-to-late adolescence is a pivotal period for susceptibility to experience a variety of negative outcomes (Rapee et al., 2019), which also appear to be associated with the intensity and problematic use of technologies and social media (Boniel-Nissim et al., 2022).

Apart from the sociodemographic variables, adolescents’ emotional intelligence (EI) is regarded as a key psychological resource that accounts for differences in levels of physical health and psychological adjustment in school contexts. Additionally, EI is consistently associated with reduced symptoms of depression, anxiety, stress, and suicidal ideation (Domínguez-García & Fernández-Berrocal, 2018; Resurrección et al., 2014). Furthermore, adolescents’ EI abilities have been found to be a protective factor against suicidal ideation both in face-to-face victimization (Galindo-Domínguez & Iglesias, 2023; Quintana-Orts et al., 2023) and cybervictimization (Elipe et al., 2015; Extremera et al., 2018). Despite the consistent empirical evidence regarding the positive link between EI and reduced suicide risk in adolescence, there is limited research regarding the potential moderating role of TEIB in the link between cybervictimization and suicide risk factors after accounting for sociodemographic variables and adolescents’ EI.

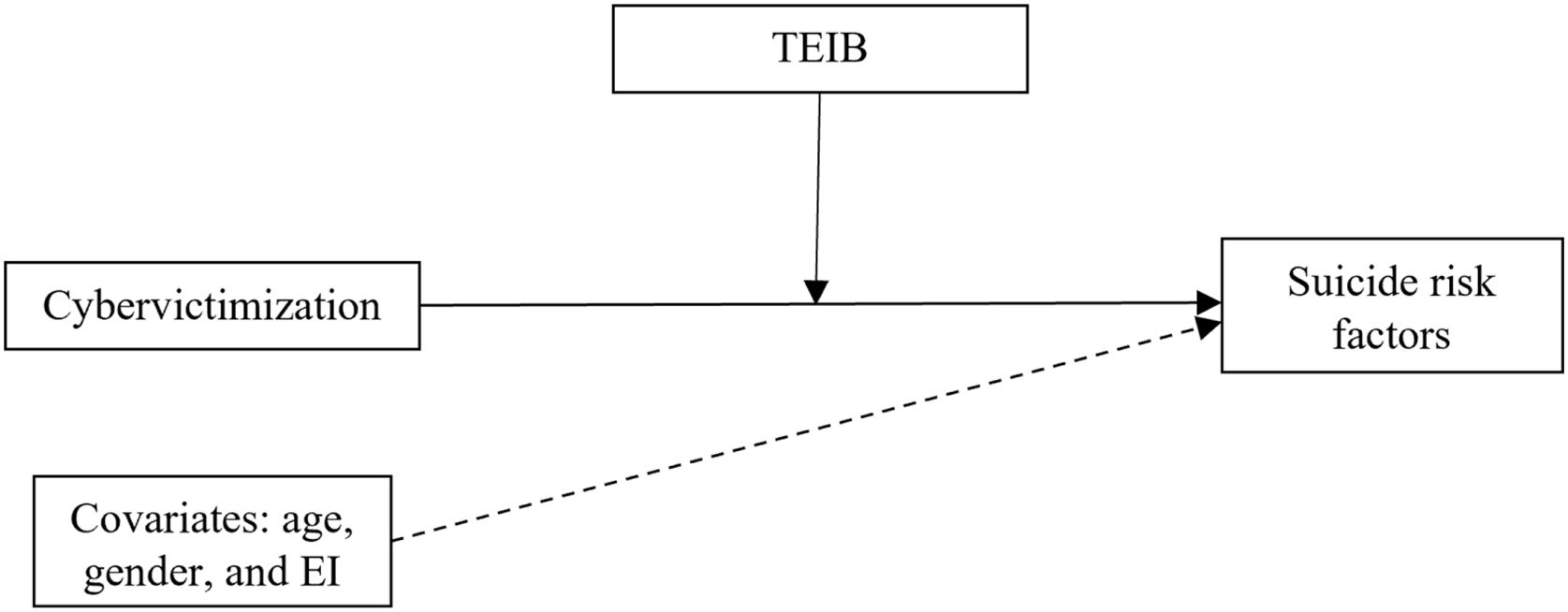

The present studyIn this study, we aimed to explore whether a school-related factor, specifically teacher emotionally intelligent behaviors (TEIB) perceived by own students, might modulate the relationship between adolescents’ cybervictimization and suicide risk factors, even after controlling for relevant sociodemographic factors (i.e., gender and age) and adolescents’ own reports of EI. These findings may expand current knowledge on how students’ perceptions about their teachers’ EI may relate to suicide risk factors and improve the generalizability of the findings while considering a salient control variable such as adolescents’ own EI (Spector, 2019). Considering existing evidence, we expected that TEIB would attenuate the relationship between cybervictimization and suicide risk factors (i.e., symptoms of depression, anxiety, stress, and suicidal ideation), even after controlling for the effects of sociodemographic factors (i.e., age and gender) and adolescents’ EI. The proposed conceptual model is depicted in Figure 1. Based upon prior theoretical and empirical evidence, the following hypotheses are proposed: (H1a) TEIB will attenuate the relationship between cybervictimization and depressive symptoms; (H1b) TEIB will attenuate the relationship between cybervictimization and anxiety symptoms; (H1c) TEIB will attenuate the relationship between cybervictimization and stress symptoms, and (H1d) TEIB will attenuate the relationship between cybervictimization and suicidal ideation.

MethodParticipantsThis study was conducted in a southern region of Spain (Málaga), with the participation of eleven different high school centers. The sample included 1,866 adolescents (996 girls, 843 boys, one transgender, eight non-binary gender, and 18 did not report their gender) whose ages ranged from 12 to 18 years (Mage = 13.99, SD = 1.44). The study focused on adolescents aged 12 to 18 years, as this age range corresponds to the student population typically found in secondary school centers where the research was conducted. The distribution of participants across the years of compulsory secondary education was: 24.7% first, 24.5% second, 24.3% third, and 22.3% fourth. Additionally, 2.7% were in the first year of their baccalaureate, while 1.5% were in their second year. Most participants were Spanish (85.5%), although 241 participants held other nationalities (12.9%), and another 29 participants did not disclose their nationality (1.6%).

InstrumentsCybervictimization was measured with the subscale of the Spanish validation (Ortega-Ruiz et al., 2016) of the European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire (ECIPQ; Del Rey et al., 2015). This subscale dimension consists of 11 items (e.g., “Someone threatened me through texts or online messages”) ranging from 0 = never to 4 = more than once a week. The Spanish version of the scale has shown great psychometric properties (Ortega-Ruiz et al., 2016). In this study, reliability was satisfactory (α = .80, Ω = .80).

Teacher emotionally intelligent behavior (TEIB) was measured with the adaptation and translation of the original scale Emotionally Intelligent Behavior among supervisors (EIB; Ivcevic et al., 2021). The original version was translated from English into Spanish using the back-translation method, and the adaptation was made by changing the word “supervisor” into “teacher.” Participants rated teachers’ EIB in 11 items (e.g., “My teacher realizes when people are dissatisfied in class”; “My teacher is good at helping others feel better when they are disappointed or upset”) using a scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree. The Spanish version of the scale has demonstrated a satisfactory model fit (χ2 = 621.74, df = 44, RMSEA = .08, SRMR = .04, CFI = .92, TLI = .90), excellent internal consistency (α = .93), and significant correlations with psychological adjustment and academic-related outcomes (Extremera et al., 2024). In this study, reliability was excellent (α = .93, Ω = .93).

Emotional intelligence (EI) was measured using the Spanish validation (Extremera et al., 2019) of the Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS; Wong & Law, 2002). The scale has 16 items (e.g., “I have good control of my own emotions”) scored on a Likert-type scale from 1 = totally disagree to 7 = totally agree. The Spanish version has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties (Extremera et al., 2019). In this study, reliability was satisfactory (α = .86, Ω = .85).

Depression, anxiety, and stress was measured using the Spanish validation (Bados et al., 2005) of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). This scale is composed of three subscales that each assess depression (e.g., “I was unable to become enthusiastic about anything”) anxiety (e.g., “I was worried about situations in which I might panic and make a fool of myself”), or stress (e.g., “I found it difficult to relax”), respectively. Every subscale contains seven items that are rated on a scale ranging from 0 = did not apply to me at all to 3 = applied to me very much or most of the time. The Spanish version of the scale has shown good psychometric properties (Bados et al., 2005). The reliability of each subscale was: depression (α = .90, Ω = .90), anxiety (α = .85, Ω = .86), and stress (α = .85, Ω = .85).

Suicidal ideation was measured using the Spanish validation (Sánchez-Álvarez et al., 2020) of the Frequency of Suicidal Ideation Inventory (FSII; Chang & Chang, 2016). The scale consists of five items (e.g., “How often have you wondered what would happen if you ended your own life?”) using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = never to 5 = almost every day. The Spanish adaptation of the scale has shown adequate psychometric properties (Sánchez-Álvarez et al., 2020). In this study, reliability was excellent (α = .92, Ω = .92).

ProcedureInitially, educational center principals were apprised of the study's details and subsequently gave written informed consent for their institution's participation. Parents or legal guardians received comprehensive information on the study's objectives through communication with the educational center. In seven of the participating educational centers, active informed consent was provided by families, indicating their explicit agreement to allow their adolescent’s involvement in the study. In contrast, the remaining four centers adopted a passive consent approach, indicating the implicit approval of families for their adolescents' inclusion in the study. The data collection procedure was carried out on a class-by-class basis, with adolescents dedicating up to two hours to complete the paper-based questionnaires. This process was conducted in the presence of one researcher and at least one high school teacher. Approved by the Ethical Committee of the hosting university (62–2016-H), this procedure ensured the anonymity of the adolescents and followed the Declaration of Helsinki (2013).

Data analysisFirst, 127 cases (6.80%) were excluded during the data cleaning process due to dubious and disengaged responses. Missing item values were then imputed using the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm in SPSS v26, a widely accepted and commonly used procedure (Liang & Bentler, 2004). Second, we conducted descriptive analyses and correlations between all variables. We used IBM’s SPSS (Version 26) for these analyses. Third, we carried out moderation analyses to test the interaction effect between cybervictimization (independent variable) and TEIB (moderator) on depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms and suicidal ideation (dependent variable). Control variables included age, gender, and adolescents’ EI. Model 1 of the PROCESS macro, Version 4.2. (Hayes, 2022) was used to conduct these analyses. The standard procedure was followed, and we performed bootstrapped bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using 5,000 bootstrapped samples. We also tested the interactions using the simple slope analysis procedure implemented in the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2022), with low and high scores of TEIB defined as one standard deviation below and above the mean, respectively.

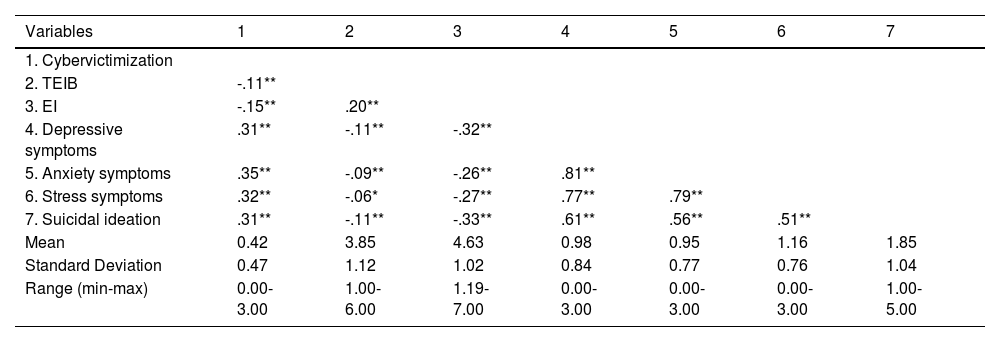

ResultsDescriptive analyses and bivariate correlationsTable 1 shows descriptive results and correlations among the study variables. In sum, cybervictimization positively and significantly correlated with all psychological distress indicators, whereas TEIB showed a negative and significant association with these indicators. The size effect of correlations between cybervictimization and suicide risk factors showed a medium size effect, whereas TEIB showed low size effects (Cohen, 1988).

Descriptive results and bivariate correlations

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cybervictimization | |||||||

| 2. TEIB | -.11** | ||||||

| 3. EI | -.15** | .20** | |||||

| 4. Depressive symptoms | .31** | -.11** | -.32** | ||||

| 5. Anxiety symptoms | .35** | -.09** | -.26** | .81** | |||

| 6. Stress symptoms | .32** | -.06* | -.27** | .77** | .79** | ||

| 7. Suicidal ideation | .31** | -.11** | -.33** | .61** | .56** | .51** | |

| Mean | 0.42 | 3.85 | 4.63 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1.16 | 1.85 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.47 | 1.12 | 1.02 | 0.84 | 0.77 | 0.76 | 1.04 |

| Range (min-max) | 0.00-3.00 | 1.00-6.00 | 1.19-7.00 | 0.00-3.00 | 0.00-3.00 | 0.00-3.00 | 1.00-5.00 |

N = between 1454 and 1852; Abbreviation: TEIB = Teacher emotionally intelligent behavior; EI = Emotional intelligence. Note. *p < .05. **p < .01.

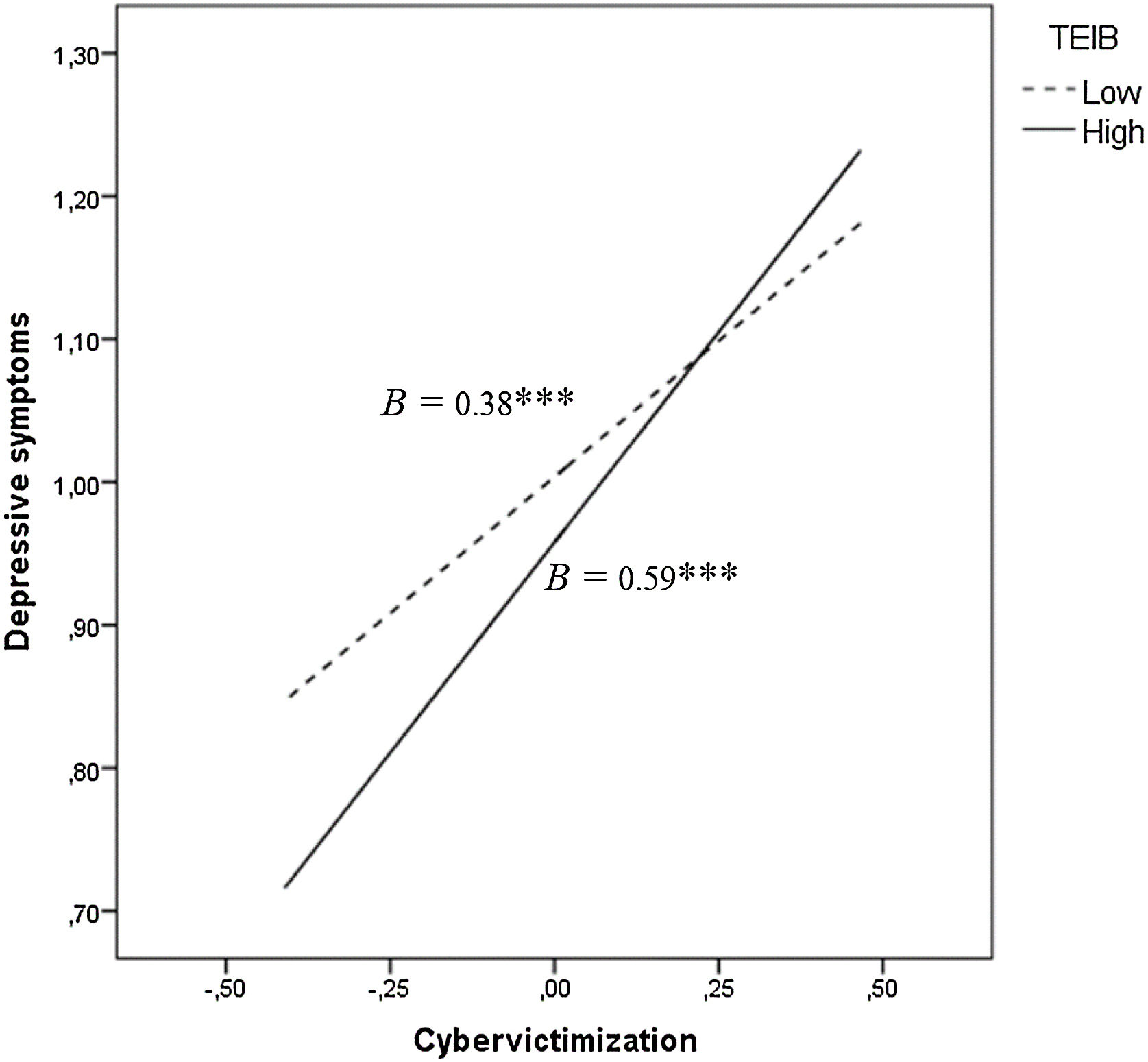

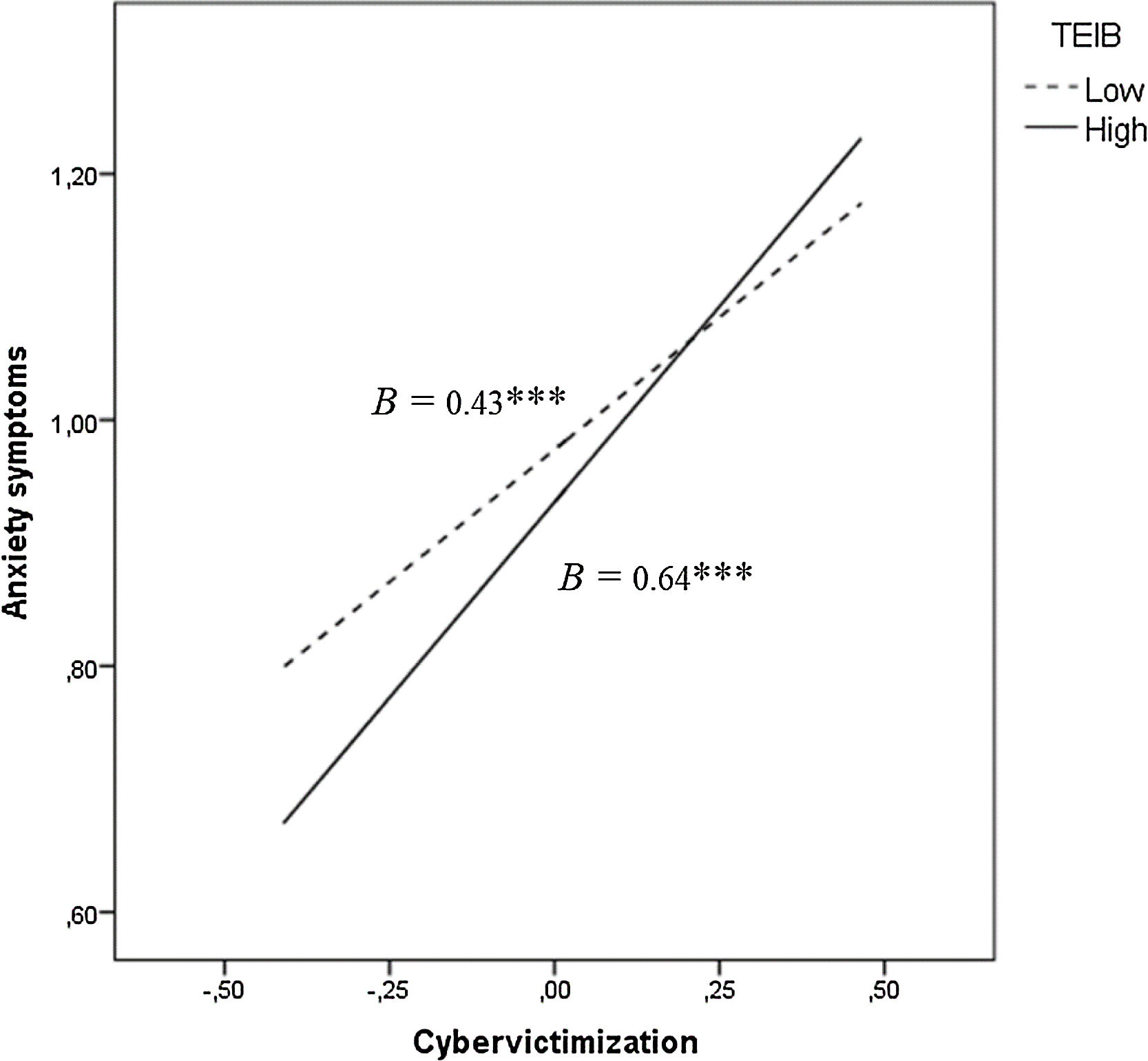

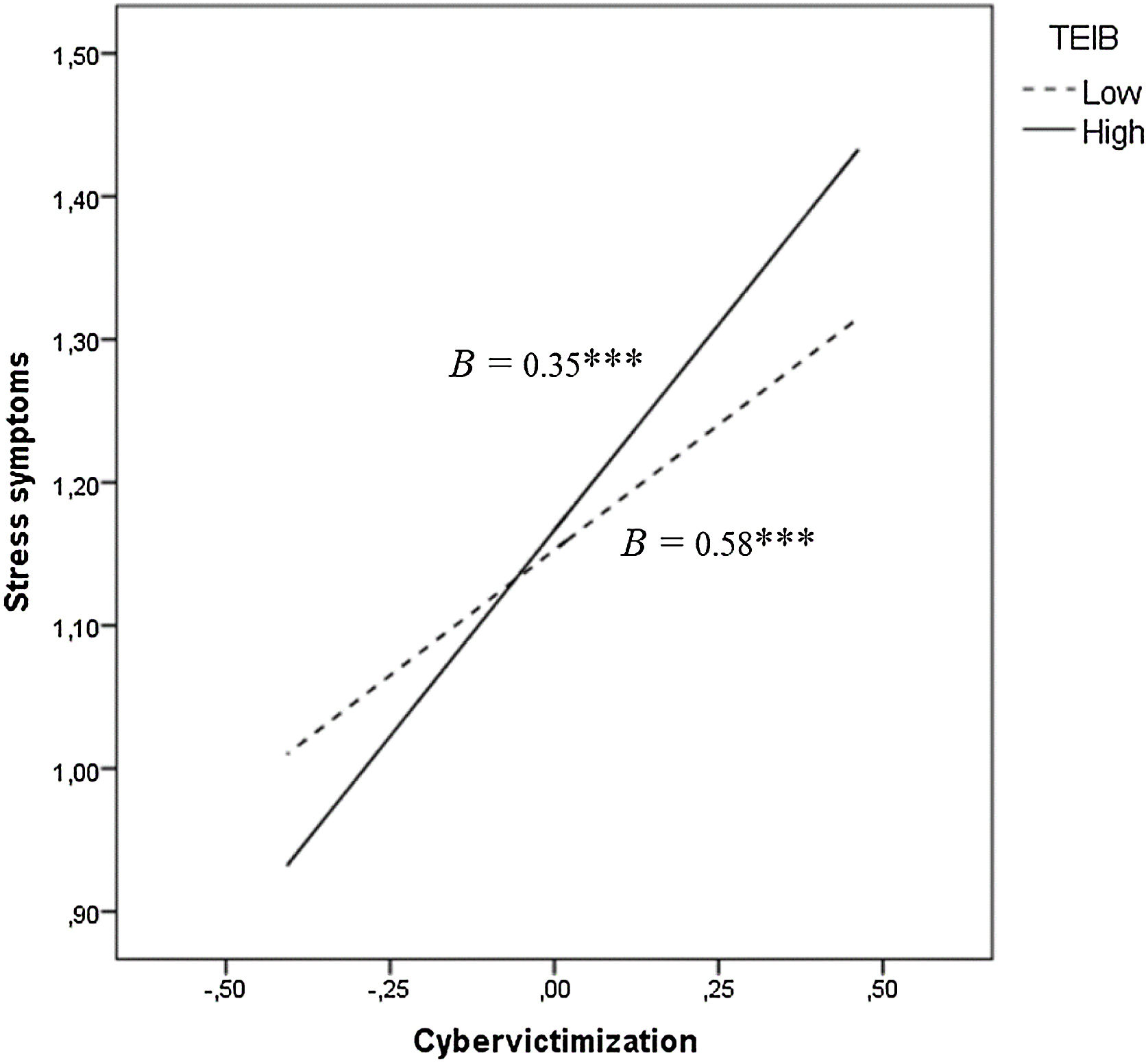

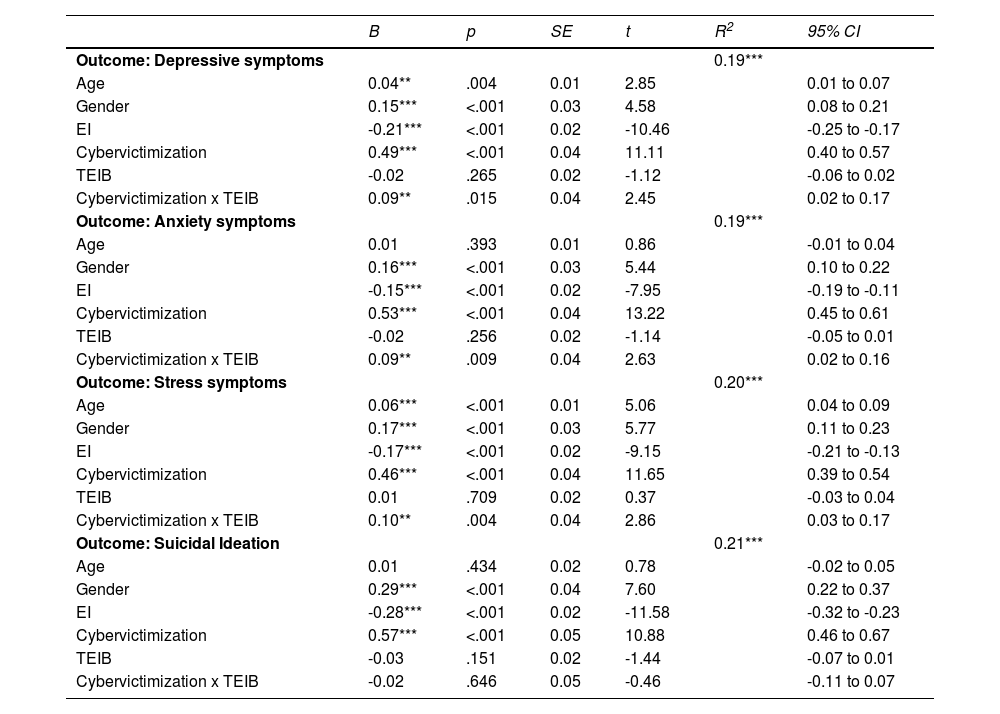

In line with H1a, H1b, and H1c, the moderating role of TEIB was tested in the relationship between cybervictimization and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. Main results are shown in Table 2. In sum, cybervictimization was a significant positive predictor of symptomatology. TEIB did not show a significant effect in predicting symptomatology once controlling for covariables and the main effect of variables. Interaction effects were significant and accounted for significant variance in symptoms of depression (ΔR2 = 0.003, F = 5.98, p = .015), anxiety (ΔR2 = 0.004, F = 6.89, p = .009), and stress (ΔR2 = 0.005, F = 8.20, p = .004) after accounting for the sociodemographic variables, EI, and main effects. Thus, proposed hypotheses H1a–H1c were supported.

Summary of moderation results

| B | p | SE | t | R2 | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome: Depressive symptoms | 0.19*** | |||||

| Age | 0.04** | .004 | 0.01 | 2.85 | 0.01 to 0.07 | |

| Gender | 0.15*** | <.001 | 0.03 | 4.58 | 0.08 to 0.21 | |

| EI | -0.21*** | <.001 | 0.02 | -10.46 | -0.25 to -0.17 | |

| Cybervictimization | 0.49*** | <.001 | 0.04 | 11.11 | 0.40 to 0.57 | |

| TEIB | -0.02 | .265 | 0.02 | -1.12 | -0.06 to 0.02 | |

| Cybervictimization x TEIB | 0.09** | .015 | 0.04 | 2.45 | 0.02 to 0.17 | |

| Outcome: Anxiety symptoms | 0.19*** | |||||

| Age | 0.01 | .393 | 0.01 | 0.86 | -0.01 to 0.04 | |

| Gender | 0.16*** | <.001 | 0.03 | 5.44 | 0.10 to 0.22 | |

| EI | -0.15*** | <.001 | 0.02 | -7.95 | -0.19 to -0.11 | |

| Cybervictimization | 0.53*** | <.001 | 0.04 | 13.22 | 0.45 to 0.61 | |

| TEIB | -0.02 | .256 | 0.02 | -1.14 | -0.05 to 0.01 | |

| Cybervictimization x TEIB | 0.09** | .009 | 0.04 | 2.63 | 0.02 to 0.16 | |

| Outcome: Stress symptoms | 0.20*** | |||||

| Age | 0.06*** | <.001 | 0.01 | 5.06 | 0.04 to 0.09 | |

| Gender | 0.17*** | <.001 | 0.03 | 5.77 | 0.11 to 0.23 | |

| EI | -0.17*** | <.001 | 0.02 | -9.15 | -0.21 to -0.13 | |

| Cybervictimization | 0.46*** | <.001 | 0.04 | 11.65 | 0.39 to 0.54 | |

| TEIB | 0.01 | .709 | 0.02 | 0.37 | -0.03 to 0.04 | |

| Cybervictimization x TEIB | 0.10** | .004 | 0.04 | 2.86 | 0.03 to 0.17 | |

| Outcome: Suicidal Ideation | 0.21*** | |||||

| Age | 0.01 | .434 | 0.02 | 0.78 | -0.02 to 0.05 | |

| Gender | 0.29*** | <.001 | 0.04 | 7.60 | 0.22 to 0.37 | |

| EI | -0.28*** | <.001 | 0.02 | -11.58 | -0.32 to -0.23 | |

| Cybervictimization | 0.57*** | <.001 | 0.05 | 10.88 | 0.46 to 0.67 | |

| TEIB | -0.03 | .151 | 0.02 | -1.44 | -0.07 to 0.01 | |

| Cybervictimization x TEIB | -0.02 | .646 | 0.05 | -0.46 | -0.11 to 0.07 |

Note. N = between 1444 and 1560; B = Unstandardized beta. SE b = Standard error. 95% CI = Confidence interval with lower and upper limits; * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001. EI = Emotional intelligence; TEIB = Teacher emotionally intelligent behavior.

In line with H1d, the moderating role of TEIB in the link between cybervictimization and suicidal ideation was tested. As shown, cybervictimization was a significant positive predictor of symptomatology, whereas TEIB did not show a significant effect. Moreover, the interaction between cybervictimization and TEIB was not significant in predicting suicidal ideation (ΔR2 = < .001, F = 0.21, p = .646). Thus, H1d was not supported.

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between cybervictimization and depression for high and low values of TEIB. As shown, the lowest values of depressive symptoms were reported among those adolescents reporting low cybervictimization and high TEIB. Similar patterns were found for symptoms of anxiety (Figure 3) and depression (Figure 4). Noteworthy, for more frequent cybervictimization cases, those adolescents reporting high TEIB reported more symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress than their counterparts reporting low TEIB.

The current work aimed to contribute to the field of EI in educational settings by examining whether TEIB may mitigate the connection between cybervictimization and suicide risk factors (i.e., depressive, anxious, and stress symptoms, and suicidal ideation) associated with cybervictimization after controlling for relevant sociodemographic factors (i.e., gender and age) and a personal resource, EI. Regarding correlational results, the findings show that TEIB was negatively correlated with both suicide risk factors, thereby extending previous studies assessing teachers’ EI and students’ indicators of functioning at school (Divecha & Brackett, 2020; Nizielski et al., 2012). According to prior research on teachers’ EI and student outcomes, it is plausible that these findings may be explained by the fact that students perceiving low TEIB may report poorer teacher-student relationships (Nizielski et al., 2012). This, in turn, would be associated with lower emotional well-being indicators (e.g., Braun et al., 2020; Jennings & Greenberg, 2009).

Regarding moderation results (H1a, H1b, and H1c), TEIB moderated the links between cybervictimization and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. In short, our results suggest that for adolescents who report low levels of cybervictimization, TEIB may have a protective effect against psychological distress symptoms. Our adolescents reported lower symptoms of psychological distress when the frequency of cybervictimization behaviors was low and, moreover, when they reported high TEIB. These results reveal that a novel construct, namely TEIB, can act as a protective factor against the consequences of cybervictimization in psychological distress even after accounting for the effect attributable to adolescents’ own EI. These findings extend previous studies’, highlighting teacher-student relationships and school connectedness as protective factors in the context of cybervictimization (Lucas-Molina et al., 2021; Nappa et al., 2020; Paniagua et al., 2022).

Surprisingly, moderation results suggested a potential dark side of TEIB between high levels of cybervictimization. Note that for cases of more frequent or severe cybervictimization, TEIB alone may not suffice to diminish the negative impact of this phenomenon on adolescents' distress. Since cybervictimization is a complex phenomenon, adolescents may benefit from additional resources related to their teachers' behaviors, such as support and behavioral strategies specifically targeting aggressive behaviors and their emotional impact (Divecha & Brackett, 2020). Thus, teachers’ resources, such as cybercompetence, may also play a role in reducing suicide risk factors beyond TEIB (Li et al., 2022). These preliminary results call for additional research that tests which and how teachers’ protective factors interact to influence adolescents’ psychological distress.

Findings did not show support for H1d, as TEIB did not moderate the link between cybervictimization and suicidal ideation. This non-significant finding may be explained in terms of the nature and assessment of the construct of suicidal ideation. Suicidal ideation is considered a multifaceted public health issue, and epidemiologic evidence shows that suicide has multiple, interacting causes and risk factors that frequently co-occur (Mościcki, 2001), including life and school stressors (Stewart et al., 2017). Therefore, the absence of significant findings could be explained by the possibility that TEIB alone might not suffice to moderate the complex relationship between cybervictimization and suicidal ideation. Not only do these findings demonstrate that TEIB perceived by students might have a specific influence on different suicide risk factors, but they also suggest that TEIB can play a particularly important role in contributing to psychological distress symptoms related to suicide risk.

Theoretical and practical implicationsRegarding theoretical implications, our results suggest that, in addition to training EI among adolescents, fostering the EI abilities of teachers might have a complementary impact on adolescents’ perceptions of their abilities to manage emotions and detect emotional information in the classroom. Such perceptions may function as a protective school-related factor that might contribute to reducing psychological distress after cybervictimization experiences. The magnitude of the size effects of the correlations and moderations was relatively modest after controlling for sociodemographic factors and adolescents’ EI. Additionally, the study variables accounted for only a relatively small amount of the variance in psychological distress symptoms, indicating that other relevant factors may have been omitted from the proposed model. Relatedly, it is possible that TEIB may serve more effectively as a protective factor against the negative effect of cybervictimization on more proximal academic attitudes (e.g., school satisfaction or study engagement) rather than on more distal outcomes such as more complex mental health problems, which might be mediated by other factors such as socioeconomic status, life stressors, or family background, among others (Extremera et al., 2024). Given the complex nature of adolescents’ suicide risk and the limited research on TEIB, further empirical studies are needed to explore these relationships. Thus, future research might consider these preliminary findings as a promising step in the development of comprehensive models that consider students’ perceptions of their teachers’ emotional abilities as school factors that minimize the detrimental effects of cybervictimization on distal suicide risk factors (Divecha & Brackett, 2020; Jennings & Greenberg, 2009). Our findings regarding the differential links between TEIB and indices of suicide risk suggest the value of considering more integrative and comprehensive models for suicide that differentiate between distal and proximal dimensions to best identify which dimensions facilitate or discourage suicide after cybervictimization.

Regarding practical implications, our results suggest that the development of emotional abilities among teachers may help in building TEIB. On the one hand, teacher EI training would enable teachers to effectively apply their emotional abilities in their daily interactions and lessons with students, which may help to create a safer and supportive environment for those suffering from the effects of cybervictimization (Brackett et al., 2019; Divecha & Brackett, 2020; Shute et al., 2022). It is crucial that teachers are provided with initial training and ongoing opportunities to enhance their EI, together with strategies to provide additional support when they address cases of cybervictimization. Furthermore, school counselors could use interventions that focus on enhancing the quality of TEIB that emphasize participation and interaction with students through emotional ability training (Brackett et al., 2019).

On the other hand, the development of emotional abilities among teachers may facilitate nurturing environments in which adolescents not only build healthier relationships but also engage in positive growth (Braun et al., 2020; Jennings & Greenberg, 2009). According to our findings, increasing TEIB might be relevant such that adolescents identify positive role models for seeking support in the context of low and occasional cybervictimization (Shute et al., 2022). Given that teachers are role models for adolescents (Nappa et al., 2020; Nizielski et al., 2012), students perceiving high TEIB may find healthy examples of relationships in their daily interactions with their teachers, which may translate into reduced psychological distress for non-victimized adolescents or among adolescents with a low frequency of cybervictimization. Programs that help teachers develop more effective ways to affectively connect with students might help increase their perceptions of TEIB and eventually associate with reduced psychological distress symptoms (Wang et al., 2013). In sum, teachers' emotional intelligence significantly affects their classroom management and interactions with students. Educational institutions can gain insights into how emotionally intelligent behaviors influence student outcomes, classroom dynamics, and overall educational effectiveness. This approach can help in developing targeted interventions and professional development programs to enhance teachers' emotional competencies, ultimately improving the development of future prevention and intervention bullying programs that consider the complementary role of school-related factors such as TEIB (Divecha & Brackett, 2020).

Limitations and future research directionsThere are several limitations that should be considered that relate to salient research avenues for future research. Our preliminary findings should be replicated with more heterogeneous samples, and random sampling techniques and more complex designs that test relationships across time would be useful. Moreover, the absence of a dedicated infrequency instrument to detect random responses is a limitation, although we addressed this by eliminating dubious responses during the data cleaning process. Furthermore, future researchers are advised to test the extent to which TEIB is significantly related with teacher self-reported and objective EI so these findings could reinforce the limited evidence on other-reported teacher EI. Indeed, the current results suggest that TEIB may have a protective effect against the impact of a low frequency of cybervictimization on psychological distress symptoms. It might be beneficial to test whether TEIB can diminish the effects of cybervictimization on indicators of positive student functioning, such as school connectedness and academic achievement. Additionally, one limitation of this study is not control for the duration of experience that students have with the teacher when evaluating TEIB in the classroom. The amount of time students spend interacting with the teacher might significantly influence their perceptions and assessments of the teacher's emotional intelligence, leading to potential biases in the evaluation results. Future research should consider this variable to ensure more accurate and reliable assessments, as judgments of emotionally intelligent behaviors may depend on this factor (Elfenbein et al., 2015). Despite these limitations, the current exploratory study can serve as a basis for conducting additional research to test TEIB as a potential school-related factor for reducing the impact of cybervictimization on suicide risks factors.

In conclusion, this study has highlighted the importance of TEIB in moderating the positive associations between cybervictimization and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. The findings suggest that interventions aimed at improving perceptions of students on their teachers’ emotionally intelligent behaviors in the classroom might effectively help mitigate the consequences of cybervictimization on students' psychological distress. Future research should further explore the role of TEIB in preventing cybervictimization among adolescents.

CRediT authorship contribution statementConceptualization: Sergio Mérida-López, Natalio Extremera; methodology & investigation: Jorge Gómez-Hombrados; formal analysis: Sergio Mérida-López, Natalio Extremera; writing - original draft preparation: Sergio Mérida-López, Cirenia Quintana-Orts, Jorge-Gómez Hombrados; writing - review & editing: Sergio Mérida-López, Cirenia Quintana-Orts, Natalio Extremera; supervision: Natalio Extremera.

FundingThis work was part of the R+D+i project PID2020-117006RB-I00, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/ and PAIDI Group CTS-1048 (Junta de Andalucía). This research was also supported by the University of Málaga. The second author was supported by the Junta de Andalucía under Grant (POSTDOC_21_00364). Partial funding for open access charge: Universidad de Málaga / CBUA.