Food allergy is common in children, occurring in 5–7.5%. The diagnosis may, however, be difficult. Elevated IgE or positive skin prick test to a food allergen is often considered proof of allergy, but may represent sensitisation without clinical manifestations. For a precise diagnosis oral challenge is necessary, but this is often not performed because of risk of serious allergic reactions. The aim of this study was to evaluate whether conjunctival provocation test would facilitate the diagnosis of IgE-mediated food allergy.

MethodsOne hundred and forty-nine children with 174 possible diagnoses of food allergy were included. General examination, skin prick test and specific IgE were performed, as well as conjunctival provocation test of the suspected food allergen. Open food challenges and double-blind placebo controlled tests were performed in order to diagnose possible food allergy.

ResultsForty-six children with strongly positive conjunctival reactions (rubor, itching, oedema) to fifty food allergens were all proven to have allergy to the food in question. The children with negative conjunctival provocation tests showed no allergic reactions when challenged.

ConclusionsWe find that a strongly positive conjunctival reaction to a food allergen correlates well with true allergy. An oral challenge should be carefully performed. With a negative conjunctival test an oral challenge may safely be performed.

Food allergy is common in children, occurring in 5–7.5%,1,2 and may be IgE or non-IgE-mediated. The diagnosis is often difficult. Oral food challenge is the only certain diagnostic tool,3,4 but in our experience, it is seldom performed in clinical practice, as the procedure is time consuming and implies the risk of serious allergic reactions, especially the IgE-mediated reactions. Diagnosis of food allergy based solely on positive skin prick test (SPT) or elevated IgE could be the result, even though this might also represent sensitisation without clinical implications.5

Furthermore, the majority of children diagnosed with food allergy in the first years of life outgrow their allergy, especially allergy to milk and egg. Re-challenge is often postponed until SPT is negative or IgE is no longer elevated, even though it is well known that SPT may be positive and specific IgE elevated for some time after clinical tolerance is achieved.5 This results in unnecessarily prolonged elimination diet, with the risk of malnutrition and poor growth,6 as well as unnecessary fear of serious adverse reactions for parents and caretakers. More appropriate methods for determining time for re-challenge have been asked for.7

Conjunctival provocation test (CPT) is one of the oldest tests used in the field of allergy. Blackley used it in the 1870s to diagnose allergy to pollen, and during the 20th century an increasing number of papers on this topic were published(8–11). Conjunctival challenges were taken into practice in some allergological institutes, but were considered relatively unsuccessful, and the practice was stopped, mainly because of the lack of additional diagnostic information (personal communication, prof K.H.Carlsen). Recently, new reports on CPT as an additional method for diagnosing allergy to inhaled allergens have been published(8,12–14). To our knowledge, there is no literature concerning the use of CPT to support the diagnosis of food allergy.

The aim of this study was to evaluate whether a positive CPT would predict food allergy, and whether a negative CPT would predict that an oral challenge could be performed without risking serious allergic reactions.

Materials and methodsA cohort of 609 children born in the Maternity Ward, Oestfold Hospital Trust, Norway, was followed from birth, in order to study food allergy during the first two years of life. Based on the medical history, 76 children were suspected of having food allergy, and thus were included in this study evaluating CPT. However, as a result of the relatively few children included, the statistical power of the study would be weak. Consequently, we applied to the Ethical Committee for the possibility of including additional children, which was approved. Seventy-three additional children, referred to a specialist clinic in Oslo, were included consecutively, giving a total of 149 patients, mean age 2.7 (0−16) years.

The symptoms/referral diagnoses were as follow: in addition to suspected food allergy 64 children had atopic dermatitis (AD), 17 had respiratory symptoms, 17 children had respiratory symptoms and AD, 32 children had gastrointestinal symptoms, and 10 of these had either respiratory symptoms or AD in addition. Nineteen children were referred simply with the question of allergy. The histories suspicious of food allergy included anaphylaxis, urticaria, angio-oedema, immediate vomiting and / or breathing difficulties after intake of a food.15

Oral and written information was given to the parents. Written informed consent was collected from those who agreed to participate. Antihistamine medication was stopped at least one week prior to the examination.

All the children underwent a general examination, with special attention to the skin, lungs, abdomen, and mucosa.

SPT: This was performed on both lower arms with a 1mm tip lancet, (ALK-Abello, Copenhagen, Denmark) with whole cow’s milk, raw and boiled egg, (prick to prick test), as well as allergen extracts from milk, egg, cod, hazel nuts, peanuts, wheat and soy (ALK-Abello, Copenhagen, Denmark). Histamine chloride10mg/ml (ALK-Abello, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used as a positive control, and NaCl 0.9% as a negative control. The SPT was read after 13min. The contours of the wheals were encircled by a pen; the two diameters perpendicular to each other were measured in mm, added and divided by two. The result was presented in mm. SPT equal to or greater than the positive control was considered positive.

Specific IgE: Blood was drawn to determine specific IgE against food allergens (cow’s milk, egg white, soy, peanuts, hazelnuts, fish and wheat) (Alastat, DPC, California, USA). The analyses were performed at the Clinical Chemistry Laboratory of Oesfold Hospital Trust (OHT). In the case of the children examined at the specialist clinic in Oslo, blood was drawn and analysed at the Department of Clinical Chemistry, Ullevaal University Hospital, Oslo. The method used was CAP (FEIA, Phadia, Uppsala, Sweden).

Conjunctival provocation testsChallenge test solutions: Whole milk was used for cow’s milk and boiled and raw eggs when this was the food in question. For other food allergens, commercially available extracts were used (ALK, Copenhagen, Denmark). The test solutions, including cow’s milk and raw eggs, were diluted with NaCl 0.9%, initially 1:40, then 1:20, 1:10, 1:5, and finally undiluted.

CPT: This was performed by placing one drop of diluted test solution of the suspected allergen in the lower conjunctival pouch of a healthy eye. The eye was observed for 15min for any sign of reaction, rubor, itching, swelling or blisters. Signs of rhinitis were noted as well. If no reaction appeared, the concentration was increased every 15min, using one eye only. For eggs, the test was performed by rubbing a cotton stick in a boiled egg, and thereafter applied to the lower conjunctival pouch. If there was no reaction, the procedure was performed with raw egg. The child was observed until the eye normalised, or at least until the reaction was markedly reduced, usually within 30–60min. CPT was performed twice, on different days, to verify positive and negative results.

Children with concomitant allergy to pollen were examined out of pollen season, and those with indoor allergy had to be without symptoms.

In Oslo two physicians, (LAA and BKK) independently scored the reactions, at the same time, and wrote down the scores, to then compare them. Only the conjunctival reactions of the children visiting the specialist clinic in Oslo were routinely scored by two physicians, as there was just one allergologist in the outpatient clinic at OHT, at any one time.

We scored the conjunctival reactions as follows:

0: No conjunctival reaction. I: Rubor/itching, undiluted test solution. II: Rubor, itching and oedema, may include blistering and rhinitis symptoms, occurring within 5min.

Elimination/challenge test: When cow’s milk allergy in an infant was suspected; the infant and/or the mother had a diet totally free from cow’s milk proteins for 14 days. Detailed dietary instructions were given. A symptom score diary card was filled out daily, with special attention to respiratory symptoms, pain behaviour recorded as crying hours, gastrointestinal symptoms and appearance of skin rashes and itching. The challenge was performed by introducing cow’s milk proteins either by formula to the infant or through the mother’s milk. The reappearance of symptoms, whether in hours or days, was noted. The challenge was considered positive with reappearance of symptoms after reintroduction of cow’s milk proteins. The change in symptoms had to be reproducible, and thus the elimination/challenge test was repeated at least once.

Open food challenge: 1.0mg of the food in question or 0.1ml of cow’s milk was given as the initial dose. The amount was increased 3, 10, 30, 100, 300, 1000 fold every 20min until an adverse reaction appeared or the last dose was reached. The children were observed for two hours after last challenge dose. A symptom score diary card was filled out during the following days.

Double-blind placebo controlled challenge (DBPC): Performed at the outpatient or specialist clinic: The clinic kitchen prepared food with and without the suspected allergen. The investigator, who was unaware of the meal content, was responsible for giving the food to the child. Beginning with a minimal dose, the amount was increased 3, 10, 30, 100, 300, 1000 fold every 20min until an adverse reaction appeared or the last dose was reached. The child was observed for two hours after the last challenge dose, and a symptom score diary card was filled out the following days. The alternative challenge was performed the following week.

The following diagnostic considerations were made: Infants exclusively breastfed were considered unsuitable for DBPC challenge, and thus elimination/challenge tests were made for the diagnosis of cow’s milk allergy.16 For comparative reasons infants fed exclusively or partly with formula were diagnosed the same way.

For older children the diagnostic procedure started with open challenge with the suspected food. If the open challenge was negative, a diagnosis of no food allergy was made. The children with positive or inconclusive open food challenge underwent DBPC challenge. However, we considered it unethical to perform DBPC challenge in children who recently had had a history of anaphylactic reaction to a food, to which the child was sensitised. We aimed at an objective diagnosis by performing a careful open challenge.

During the diagnostic procedure, we ended up with four groups of children according to CPT, IgE and SPT: Group 1: conjunctival score II, elevated IgE and positive SPT; Group 2: conjunctival test score I, elevated IgE and positive SPT; Group 3: negative CPT, but elevated IgE and positive SPT; and Group 4: no elevated IgE and no positive SPT. These children were then included as controls, CPT performed with the food allergens most frequently causing allergy.

Statistical methods: Mean and Standard deviation (SD) or median and Interquartile Range (IQR), when appropriate, was used as index of location and index of dispersion. The sensitivity and specificity was calculated as described in Altman.17 A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was computed 17 to assess the usability of IgE as a diagnostic tool. The analysis was performed using Number Cruncher Statistical System (NCSS, Kaysville, Utah, USA) version 2007. All p-values equal to or below 0.05 were considered significant.

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee.

ResultsOne hundred and forty-nine children were examined with regard to different food allergies, and revealed one hundred and seventy-four possible diagnoses of food allergy, based on history, IgE and SPT.

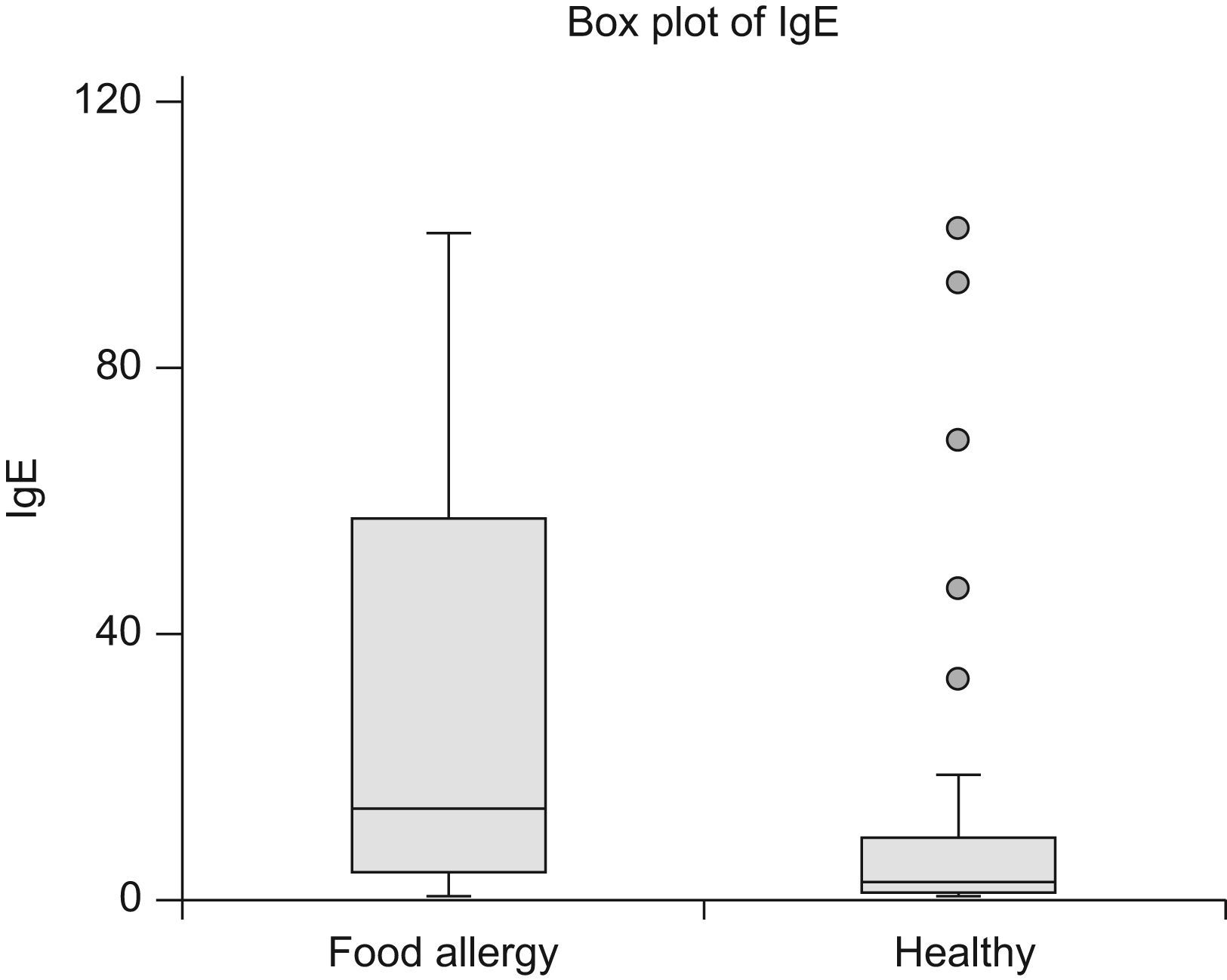

As demonstrated in Table 1 the children in Group 1 were all proven to be allergic to the suspected foods. Median specific IgE to the suspected food allergens was 13.65kU/l, (95% Confidence Interval (CI) 7.98–27.00) (Figure 1), and mean SPT was 7.1mm, (3−15). The allergens were milk,11 eggs,14 peanut 22 and fish.3

Conjunctival score, compared to IgE, SPT and diagnosis

| Group | Score | Number of diagnoses | Age, years | IgE, kU/l | SPT, mm | Food allergy | No food allergy |

| 1 | II | 50 | 3.5 (0.3–13.6) | 0.35 to >100 | 7.1 (3–15) | 50 | 0 |

| 2 | I | 24 | 1.7 (0.5–4.8) | 0.42 to >100 | 5.0 (3–12) | 8 | 16 |

| 3 | 0 | 50 | 3.0 (0.3–8.2) | 0.58 to >100 | 4.4 (3–10) | 0 | 50 |

| 4 | 0 | 50 | 2.1 (0.1–16.2) | <0.35 | 0 | 27¿ | 23 |

Age in the forth column refers to the age when the diagnosis was confirmed.

Twenty-eight children had histories of anaphylaxis 15 to the foods in question, resulting in emergency visits to hospital or physician. The diagnoses were verified by open challenge, except two children, who had recent histories of anaphylaxis. In twenty-two cases the diagnoses of food allergy were proven by DBPC challenge. These reactions were mainly urticaria, some with breathing difficulties and some with vomiting as well.

In Group 2, the diagnostic challenge revealed eight diagnoses of food allergy, and no allergy in sixteen cases. Median specific IgE was 1.17kU/l (95% CI 0.53−5.42), mean SPT was 5mm (3−12) (Table 1). The foods in question were milk,11 eggs 7 and peanuts.6 All food allergy diagnoses were made after DBPC challenge, six of no food allergy by open food challenge. The eight children with food allergies had mild reactions, mainly worsening of AD.

In Group 3, negative CPT but elevated IgE/positive SPT, no adverse reactions could be demonstrated by open challenges. Median specific IgE was 2.42kU/l (95% CI 1.74–4.73) (Figure 1), mean SPT was 4.4mm (3−10). (Table 1). The foods in question were cow’s milk,15 eggs,23 peanuts,3 hazelnuts,1 soy 5 and wheat.3

In Group 4, with no detectable specific IgE and no positive SPT to any food allergen, there were no positive CPT (Table 1). The majority of these children were infants, suspected to be allergic to cow’s milk, and thus the conjunctival test solution was milk. In addition to milk; eggs, fish and peanuts were tested. Non-IgE-mediated allergy to cow’s milk was demonstrated by elimination/challenge test in 27 infants, none with serious reactions. Twenty-three children had no adverse reactions to any food allergen.

The usefulness of CPT and IgE alone is given in Table 2. Sensitivity and specificity were calculated for score II and 0 only. The total number of patients in the analysis was 100. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of IgE as diagnostic tool for allergy was made.

| N | Variable | Value (95% CI) |

| Diagnosing food allergy using elevated IgE | ||

| 100 | Sensitivity | 0.88 (0.76, 0.94) |

| 100 | Specificity | 0.43 (0.32, 0.55) |

| 100 | PPV | 0.53 (0.42, 0.63) |

| 100 | NPV | 0.83 (0.68, 0.92) |

| Diagnosing food allergy using CPT score 0 and score II | ||

| 100 | Sensitivity | 1.0 (0.93, 1.0) |

| 100 | Specificity | 1.0 (0.93, 1.0) |

| 100 | PPV | 1.0 (0.93, 1.0) |

| 100 | NPV | 1.0 (0.93, 1.0) |

In the present study we have demonstrated a positive diagnosis of food allergy in 50 cases with conjunctival reactions score II to the food allergen in question. None of the children with positive SPT and elevated IgE, but negative CPT, score 0, had any obvious adverse reactions to food challenge. In the group of children with score I positive conjunctival reaction, eight diagnoses of food allergy were made, while in 16 cases food allergy was not demonstrated by challenge.

Food allergy may be IgE or non-IgE-mediated. A certain diagnosis is made on the background of oral food challenge. The diagnosis of non-IgE-mediated allergy is made solely on history and challenge as no test suggestive of the diagnosis exists, but challenge seldom implies risk of serious adverse reactions, and thus is easily performed. IgE-mediated allergies, however, may cause serious reactions, but on the contrary positive SPT and elevated IgE may represent sensitisation without clinical symptoms.5 Thus IgE-mediated food allergy may be a diagnostic challenge. For certain food allergens the magnitude of specific IgE in serum or the size of the prick wheal diameter may indicate if a positive challenge is probable.18–20 Cut-off values for IgE, as well as for SPT, have been suggested in order to decide when a food challenge is indicated or may be superfluous.20 However, the clinician seeing the individual patient may still be uncertain, as serious food allergy may be present with a low specific IgE, and no clinical allergy may be demonstrated even with IgE>100kU/l. Twenty-seven of the children with food allergy in our study had IgE-levels below the 95% positive predictive value given in the literature,20 13 with serious reactions. Four of the children with negative CPT in our study, had IgE-levels above the 95% positive predictive value,20 but showed no allergic reactions when challenged with the food in question (Figure 1).

In our clinical experience we have found that CPT is useful, simple and reliable in diagnosing IgE-mediated food allergy in daily practice. In this study, the sensitivity and specificity, as well as the positive and negative predictive value (PPV, NPV), are better for CPT (score II and 0) than for specific IgE alone. Using conjunctival score II and 0, the 50 cases of food allergy and the 50 healthy ones were diagnosed correctly, giving a specificity, sensitivity, PPV and NPV of 1.00 (95% CI .93, 1.00). (Table 2). When ROC analysis for IgE as a diagnostic tool was performed, the sensitivity was acceptable, whereas the specificity was far below the accepted levels. The Positive Predictive Value, although, calculated from this sample only, was on the low side. The Negative Predictive Value was acceptable (Figure 2).

Although a comparison between food allergens and inhaled allergens is somewhat dubious, Bertel et al. found a better accuracy for CPT than IgE and SPT with regard to the diagnosis of mite allergy. These authors, as well as Bonini et al., also conclude the CPT to be useful, rapid and perfectly safe.12,21

The scoring system of three levels was made to make CPT an easy tool in clinical practice. The extensive scoring system for CPT and allergic conjunctivitis by Abelson is detailed but not complicated.22 For infants and small children however, it is not applicable, especially because of the itching score.

The usefulness of CPT in food allergy for children in the intermediate (score I) group may be questioned as it may represent a true food allergy or no allergy at all. The children in this group, however, experienced no serious allergic reactions to food challenges. The number of children in this group was too small to allow calculations of specificity, sensitivity, PPV and NPV.

In the control group, there were no observable signs of injection or other side effects of the placement of a drop of food allergen on the conjunctiva, indicating that there are no irritating or other harmful effects of this procedure. The producer of the test solutions confirms that none of the components of the test solutions harm the mucosal surfaces.

However, the procedure does run the risk of explicit reactions, such as severe oedema, rubor, itching and theoretically, serious allergic reactions. The risk is reduced by starting with a highly diluted allergen. Washing the eye with NaCl 0.9%, and thereafter giving the child a dose of antihistamine will minimise the symptoms of a positive reaction. None of the children in our study experienced serious allergic reactions.

It may be argued that introducing food on the lips or oral mucosa would be more appropriate for diagnosing food allergy, but we consider CPT preferable as the visual difference between a negative and a positive test is more obvious. That the difference between score I and score II reaction is normally easily detected, is supported by the fact that two investigators (BKK and LAA) did the scoring independently, without disagreement.

CPT was well tolerated by infants as well as older children, parents and staff.

CPT is only suitable for children with suspected IgE-mediated allergy. Twenty-seven children in our cohort with negative conjunctival test to milk were diagnosed with non-IgE-mediated allergy to cow’s milk.

A disadvantage of this study was the inclusion of additional children, not belonging to the original cohort, as well as the use of two laboratories, having different systems, CAP and DPC. The values of the laboratories are, however, regularly compared, as part of laboratory quality testing, and the values are consistently within the same range, though not exactly comparable. This would have no consequences for the outcome of the study, as all patients with elevated IgE were identified as such, irrespective of the laboratory method applied. SPT was also performed in all the children.

The present study indicates that reactions in the conjunctiva may be better predictors of IgE-mediated food allergy than skin prick tests and measured IgE in blood. The reason for this is not clear, but one may speculate that immunological reactions in the mucosa of the eye may mimic immunological reactions in the mucosa of the gastrointestinal tract. If so, this may explain why a patient reacting with conjunctivitis to pollen, may have oral allergic symptoms to fruit and vegetables that share the same allergens.23

In conclusion we have demonstrated that a strongly positive CPT to a certain food allergen correlates well with a true food allergy, and consequently an oral challenge should be performed carefully to avoid serious allergic reactions. With a negative CPT to a food allergen, an oral challenge can safely be performed without risking serious allergic reactions.

Conflict of interestNone.

The authors would like to forward their sincere thanks to the staff in the Children’s Department of Oestfold Hospital Trust, as well as the staff in Children’s Allergological Clinic, Oslo, for their participation in the project.

We are grateful to MSc Petter Mowinckel, Ulleval University Hospital, for help with the statistics.

We are also grateful to Suzanne Crowley, Voksentoppen, Department of Pediatrics, Rikshospitalet-Radiumhospitalet Medical Senter, Oslo, for help with the English language of the manuscript.

A special thank you to Laila Aaserud for help with the scoring of the CPT.