Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a primarily polygenic allergic disorder. Although most patients have IgE sensitization, it seems that non-IgE mediated responses mainly contribute to the pathogenesis of EoE. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) may have an important role in allergies. There are limited data on the association of Tregs and EoE. In this study, we enumerated and compared T lymphocytes and Tregs in esophageal tissue of patients with EoE, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and normal controls.

MethodsTen patients with EoE, ten patients with GERD and eight normal controls were included. Immunohistochemistry staining was used to enumerate T lymphocytes and Tregs. CD3+ cells were considered as T cells and FOXP3+, CD3+ cells were considered as Tregs. T cells and Tregs were counted in 10 high power fields (HPF) (×400) for each patient and the average of 10 HPFs was recorded.

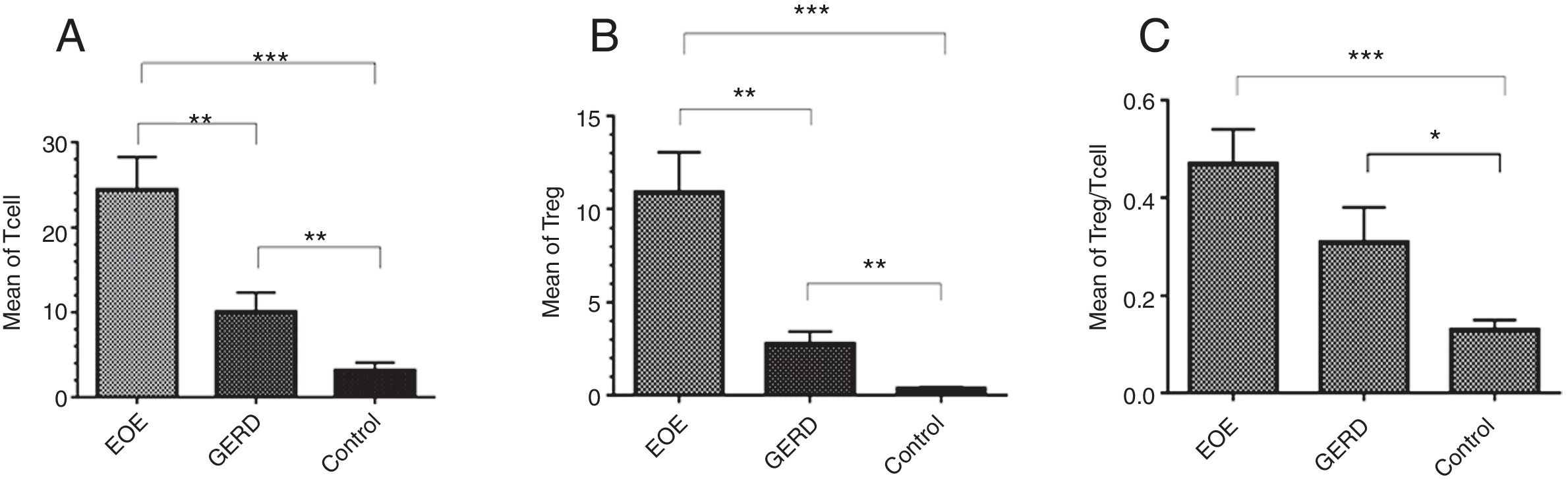

ResultsThe mean±SEM of Tregs in esophageal tissue of patients with EoE (10.90±2.14cells/HPF) was significantly higher than the GERD (2.77±0.66cells/HPF) and control groups (0.37±0.08cells/HPF) (P<0.001). Additionally, the mean±SEM of T lymphocytes in esophageal tissue of patients with EoE (24.39±3.86cells/HPF) were increased in comparison to the GERD (10.07±2.65cells/HPF) and control groups (3.17±0.93cells/HPF) (P<0.001).

ConclusionThere is an increase in the number of esophageal T lymphocytes and regulatory T cells in patients with EoE compared to the GERD and control groups.

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is one of the eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders that involve both IgE-mediated and delayed Th2 responses. The normal esophagus tissue does not contain any eosinophils, and finding eosinophils in esophageal epithelium indicates a pathologic disorder.1–3 Patients typically suffer from vomiting, epigastric or chest pain, dysphagia, and food impactions.4 Symptoms are similar to those of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Quantitation of eosinophils is helpful to distinguish EoE from GERD. Up to seven eosinophils/HPF (×400) is most indicative of GERD, while more than 15 eosinophils/HPF is characteristic of EoE.5 There has been an increase in the prevalence and incidence of the disease in the last decade.6

Eosinophilic esophagitis is considered as a chronic antigen driven disease, in which food and/or aeroallergens induce an eosinophilic infiltration in the esophagus.7 Although most patients have IgE sensitization, it seems that non-IgE mediated responses mainly contribute to the pathogenesis of EoE.3 Most EoE patients have another allergic disease such as food sensitivity, eczema, allergic rhinitis and asthma.8–10 Some studies11,12 suggest that regulatory T cells (Tregs) that express the forkhead box P3 (FoxP3) gene are crucial in protecting against allergic diseases and maintaining self-tolerance. Reduction in the frequency or function of Tregs has been reported to be associated with allergies and eosinophilia.11–14 It has also been found that total thymic Foxp3 mRNA expression is increased in non-atopic children, whereas Treg cell maturation is significantly delayed in atopic children.15 There are limited data on the association of Tregs and EoE.6,16–18

This study was designed to enumerate Tregs in esophageal tissue of pediatric patients with EoE in comparison to patients with GERD and normal controls.

Materials and methodsThis prospective study was performed on pediatric patients of Mofid Children's Hospital, Tehran, Iran. Ten patients with EoE, ten patients with GERD and eight normal controls were included. The EoE group consisted of patients with at least 15 eosinophils/HPF in evaluation of H&E slides of esophagus biopsy, normal PH in esophagus and were not responsive to anti-reflux therapy (pantoprazole or esomeprazole) for four to eight weeks. The GERD group had fewer than 15 eosinophils/HPF in esophageal biopsy and low PH in esophagus. The control group was defined as those who did not have an eosinophilic process or any pathologic findings in their biopsies. Subjects were age matched in the groups. Allergic histories of the patients were also studied. Any patient with autoimmune disease or those taking any form of immunosuppressive drugs such as corticosteroids were excluded.

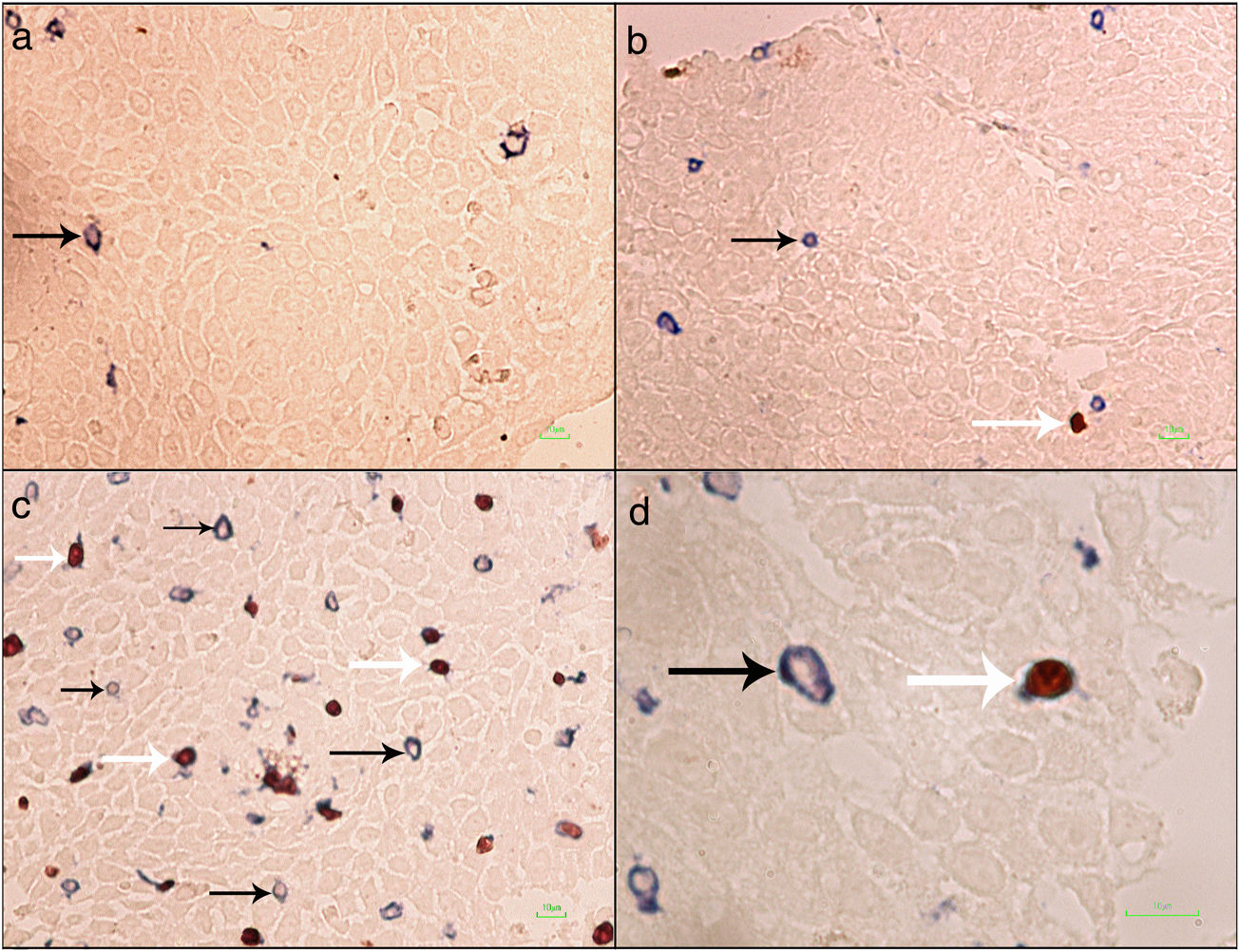

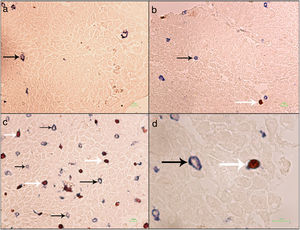

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples were sectioned at 4μm and put on IHC slides. Deparaffinization and rehydration were performed. To neutralize the tissue peroxidase, hydrogenperoxide (H2O2) 3% was used, and then antigen retrieval was done. Monoclonal mouse anti FOXP3 antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was applied at a dilution of 1:100 and incubated for 2h followed by monoclonal rabbit anti CD3 antibody (Biocare Medical, California, USA) for 1.5h. MACH 2 Double Stain 2 Mouse-HRP + Rabbit-AP, Polymer Detection Kit (Biocare Medical, California, USA) was used for secondary antibody staining for 1h. As chromogens, DAB (3,3′-diaminobenzidine) (BioGenex, California, USA) and Ferangi Blue™ Chromogen Kit 2 (Biocare Medical, California, USA) were applied. Eosin was used as counter stain. Tregs were identified as cells that stained for CD3 circumferentially and FoxP3 intracellularly (CD3+/FoxP3+). T cells were identified as cells single stained with CD3 (CD3+) (Fig. 1). For each slide 10 HPF (×40) were counted twice and the mean was reported. Statistical analysis was done by the SPSS21 and GraphPad Prism6 software. The results were reported as mean±SEM. Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare the three groups. For comparing two groups the Mann–Whitney U test was used. P value <0.05 was considered significant.

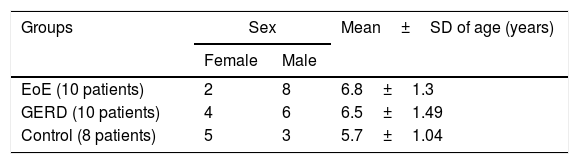

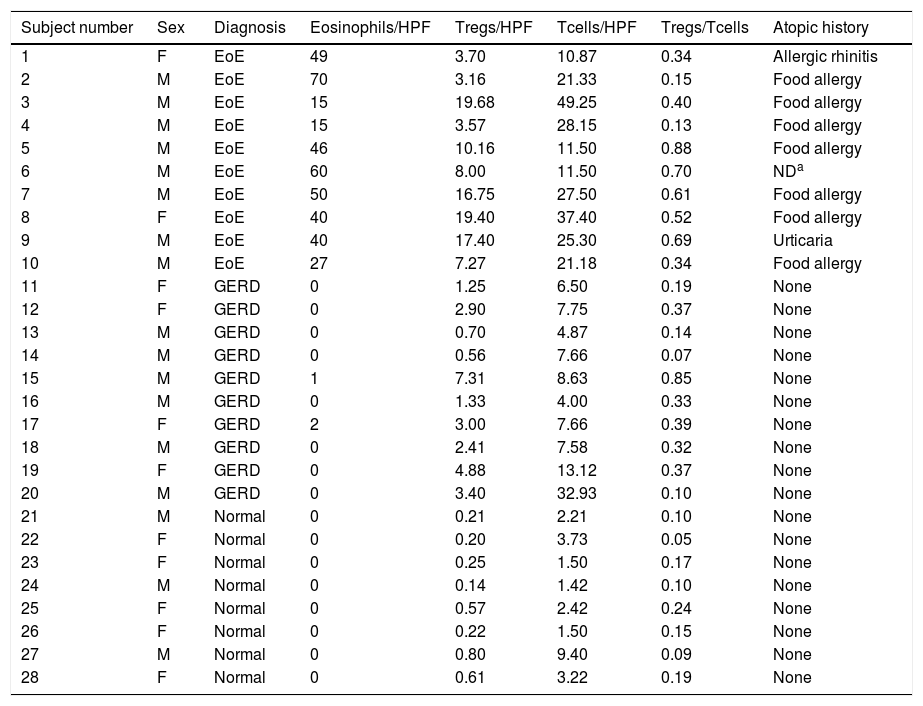

ResultsA total of 28 children were studied. There was no significant difference between the ages of the three groups (P=0.86) (Table 1). The characteristics of the patient in all three groups are summarized in Table 2.

Characteristics of 28 subjects with EoE, GERD, and controls.

| Subject number | Sex | Diagnosis | Eosinophils/HPF | Tregs/HPF | Tcells/HPF | Tregs/Tcells | Atopic history |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | EoE | 49 | 3.70 | 10.87 | 0.34 | Allergic rhinitis |

| 2 | M | EoE | 70 | 3.16 | 21.33 | 0.15 | Food allergy |

| 3 | M | EoE | 15 | 19.68 | 49.25 | 0.40 | Food allergy |

| 4 | M | EoE | 15 | 3.57 | 28.15 | 0.13 | Food allergy |

| 5 | M | EoE | 46 | 10.16 | 11.50 | 0.88 | Food allergy |

| 6 | M | EoE | 60 | 8.00 | 11.50 | 0.70 | NDa |

| 7 | M | EoE | 50 | 16.75 | 27.50 | 0.61 | Food allergy |

| 8 | F | EoE | 40 | 19.40 | 37.40 | 0.52 | Food allergy |

| 9 | M | EoE | 40 | 17.40 | 25.30 | 0.69 | Urticaria |

| 10 | M | EoE | 27 | 7.27 | 21.18 | 0.34 | Food allergy |

| 11 | F | GERD | 0 | 1.25 | 6.50 | 0.19 | None |

| 12 | F | GERD | 0 | 2.90 | 7.75 | 0.37 | None |

| 13 | M | GERD | 0 | 0.70 | 4.87 | 0.14 | None |

| 14 | M | GERD | 0 | 0.56 | 7.66 | 0.07 | None |

| 15 | M | GERD | 1 | 7.31 | 8.63 | 0.85 | None |

| 16 | M | GERD | 0 | 1.33 | 4.00 | 0.33 | None |

| 17 | F | GERD | 2 | 3.00 | 7.66 | 0.39 | None |

| 18 | M | GERD | 0 | 2.41 | 7.58 | 0.32 | None |

| 19 | F | GERD | 0 | 4.88 | 13.12 | 0.37 | None |

| 20 | M | GERD | 0 | 3.40 | 32.93 | 0.10 | None |

| 21 | M | Normal | 0 | 0.21 | 2.21 | 0.10 | None |

| 22 | F | Normal | 0 | 0.20 | 3.73 | 0.05 | None |

| 23 | F | Normal | 0 | 0.25 | 1.50 | 0.17 | None |

| 24 | M | Normal | 0 | 0.14 | 1.42 | 0.10 | None |

| 25 | F | Normal | 0 | 0.57 | 2.42 | 0.24 | None |

| 26 | F | Normal | 0 | 0.22 | 1.50 | 0.15 | None |

| 27 | M | Normal | 0 | 0.80 | 9.40 | 0.09 | None |

| 28 | F | Normal | 0 | 0.61 | 3.22 | 0.19 | None |

EoE: eosinophilic esophagitis; GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease; HPF: high-power field; Treg: regulatory T cells; M: male; F: female.

Regulatory T cells and T lymphocytes were counted on epithelium layer of esophagus tissue (Fig. 1). The mean±SEM of Tregs in esophageal tissue of patients with EoE (10.90±2.14cells/HPF) was significantly higher than the GERD (2.77±0.66cells/HPF) and control groups (0.37±0.08cells/HPF) (P<0.001). Additionally, the mean±SEM of T lymphocytes in esophageal tissue of patients with EoE (24.39±3.86cells/HPF) were increased in comparison to the GERD (10.07±2.65cells/HPF) and control groups (3.17±0.93cells/HPF) (P<0.001). To clarify whether the increased number of Tregs is because of increased T lymphocytes or it is an independent phenomenon, the ratio of Treg/T lymphocytes was calculated. This ratio was higher in EoE (0.47±0.07) and GERD patients (0.31±0.07) in comparison to normal controls (0.13±0.02) (Fig. 2).

There was no significant correlation between the number of Tregs and the number of eosinophils (r=−0.04, P=0.90). Moreover, no correlation was detected between the number of T cells and the number of eosinophils (r=−0.66, P=0.05).

DiscussionEosinophilic esophagitis is a chronic eosinophilic inflammatory disease of the esophagus. Although most patients have IgE sensitization, it seems that non-IgE mediated responses have a more important role in pathogenesis of EoE.3,10

There is a strong relation between EoE and atopy.10,19–21 In this study almost all the patients had a concomitant allergic disorder along with EoE, such as food allergy, allergic rhinitis and urticaria (Table 2). Atopic sensitization commonly occurs early in life if epithelial barrier integrity is compromised and the epithelium becomes aberrantly activated.22 Recent studies report structural and functional impairment of the esophageal epithelial barrier in EoE. This impairment, which might be related to the patient's genetic background, microbiota, food allergy, etc., might promote allergic sensitization.23 Barrier dysfunction allows allergens to activate the epithelium and produce cytokines that skew the immune system to T helper type 2 (Th2) responses.24 In humans, allergen-specific Th2 cells are essential for triggering non-IgE-mediated food allergies as well as maintaining type I IgE-mediated allergic responses. In allergic individuals, allergen-specific T cells in blood proliferate more in response to food allergens compared with non-allergic individuals, and human milk-specific T cells derived from duodenum have a dominant Th2-type cytokine secretion profile.25,26 The results of the present study show that the number of T lymphocytes in esophageal biopsy of EoE patients is significantly increased in comparison to GERD and control groups (Fig. 2). As EoE is an allergic disease, so a significant increase of Tcells in the epithelial layer of esophagus in comparison to the control group suggests a probable important role of these cells in the pathogenesis of the disease.

Th2-type cytokines including IL-13, induce production of Eotaxin-3 by epithelial cells that can recruit eosinophils. IL-5 secreted by Th2 cells also activate eosinophils. Triggering eosinophils through engagement of cytokine receptors, immunoglobulins, and complement can lead to the generation of a wide range of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, GM-CSF, transforming growth factors, TNF-α, RANTES, macrophage inflammatory protein 1α, vascular endothelial cell growth factor, and eotaxin 1, indicating that they have the potential to modulate multiple aspects of the immune response.1 Although the results of this research did not show a significant correlation between the number of eosinophils and T lymphocytes in EoE patients, it is likely that eosinophils have activated lymphocytes and lymphocytes might have activated eosinophils and exacerbated EoE symptoms.

Several studies have indicated that Tregs have an important role in preventing allergy.11,12 The present study shows that the number of Tregs in the EoE group is significantly higher than the GERD and control groups. Also, the ratio of Treg/Tcell in EoE in comparison to GERD and control groups was higher, which indicates that augmentation of Tregs does not merely depend on T lymphocyte increase. Increased numbers of Tregs have been previously reported in two similar studies in children,5,15 but Stuck et al. showed that despite increased infiltration of CD3+ T cells in the epithelial layer of esophagus of adult patients with EoE, the number of regulatory T cells is decreased.18 The reason for this discrepancy has not yet been explained but might be due to a different pathophysiological mechanism of EoE development in adults and children. High infiltration of Tregs has also been reported in other allergic diseases such as asthma,27 chronic rhinosinusitis28 and atopic dermatitis.29

Eosinophils are expanded in inflammation cites in allergic diseases and they are the main source of TGF-β. It has been shown that asthmatic patients have a greater expression of TGF-β1 mRNA than normal control subjects.30 Expression of TGF-β in nasal polyps of patients with allergic rhinitis, having large number of eosinophils, is also enhanced in comparison to the control group.31 Since TGF-β is an important factor in the differentiation of Tregs, it seems that FOXP3+ cells are induced Tregs (iTregs) that are induced in tissue in the presence of TGF-β, similar to the condition that food allergen gavage to Balb/C mice induce iTreg in GALT to prevent allergic reactions.32 Therefore, it seems that the Tregs infiltrated in eosinophil rich tissues in this study are mainly iTregs and further studies are demanded to evaluate the presence and role of different Treg subsets in EoE.

Tregs are essential for the maintenance of tolerance especially in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Most Tregs in GI tract are iTregs, induced by chronic antigen exposure (e.g. to food or microbial antigens). A substantial part of nTregs and iTregs might lose their FOXP3 expression in specific inflammatory conditions and differentiate into Th1 or Th17 lymphocyte subsets and aggravate the inflammation. Some other Tregs that have lost their FOXP3 expression might differentiate into T follicular helper cells that have a role in humoral immunity.33,34 The co-increase of Tregs and T lymphocytes in esophageal biopsy of the patients in this study – at least to some extent – can be due to Treg plasticity and the change of Tregs to T helper cells under inflammatory condition of EoE. Characterization of other T cell subsets (Th1, Th2, and Th17) in esophageal biopsy of EoE patients can shed light on this point.

Epigenetic modification like methylation and demethylation has an important role in gene expression. FOXP3 gene, the main factor in Treg differentiation, is the target of these modifications. FOXP3 gene is demethylated and has a constant expression in natural Tregs (nTregs), but human TGF-β induced Tregs undergo a partial demethylation in the FOXP3 gene. This expression is temporary and will be silent after several days. It seems these cells with temporary expression of FOXP3 are less effective on the suppression and regulation of immune responses than nTregs.35

To conclude, according to the results of the present study, the number of esophageal Tregs and T lymphocytes are increased in EoE patients in comparison to GERD and control groups. Under the inflammatory condition leukocytes including T lymphocytes migrate to the inflammation site. This can explain the increased number of T lymphocytes in esophageal epithelium of EoE patients. It seems that the presence of a large number of eosinophils in esophagus tissue can induce Tregs by producing TGF-β. These cells may not be fully functional, as they are not successful in suppressing the inflammation. The study of Treg subtypes, their function, and other TH lymphocytes subsets can help to understand more about this disease.

Statement of ethicsThe study was ethically approved by the ethical committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (approval number: IR.SBMU.RAM.REC.1394.118). All parents signed an informed consent.

Funding sourceThis research was funded by a grant (No. 5869), provided by Pediatric Pathology Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Authors’ contributionFatemeh Mousavinasab: design of the work, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, drafting and revising the manuscript.

Delara Babaie: design of the work, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, revising the manuscript.

Yalda Nilipour: design of the work, acquisition of data.

Mahboubeh Mansouri: design of the work, acquisition of and interpretation of data.

Farid Imanzadeh: acquisition and interpretation of data.

Naghi Dara: acquisition and interpretation of data.

Pejman Rohani: acquisition and interpretation of data.

Katayoon Khatami: acquisition and interpretation of data.

Aliakbar Sayyari: acquisition and interpretation of data.

Maliheh Khoddami: acquisition of data.

Maryam Kazemiaghdam: acquisition of data.

Mehrnaz Mesdaghi: design of the work, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, revising the manuscript.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

The authors wish to thank Ms. Zaynab Nasehi for her technical assistance.