Allergic diseases have become an increasingly common reality in the last years, extending beyond the family context.

ObjectiveAssessing the level of knowledge on asthma, food allergies and anaphylaxis of asthmatic children's parents/caregivers (PC), elementary school teachers (EST) and university students (US) in Uruguaiana, RS, Brazil.

Method577 individuals (PC – N=111; EST – N=177; US – N=299) took part in the study, answering the Newcastle Asthma Knowledge Questionnaire (validated for Portuguese) and another questionnaire on Food Allergy (FA) and anaphylaxis.

ResultsAlthough PC have asthmatic children, their asthma knowledge level was average, slightly above that of EST and EU. The lack of knowledge on passive smoking, use of medications and their side effects should be highlighted. US have shown to be better informed about FA and anaphylaxis. However, even though a significant proportion of respondents know the most common symptoms of FA and anaphylaxis, few named subcutaneous adrenaline as the drug of choice for treating anaphylaxis. Although a significant number of respondents know about the possibility of anaphylactic reactions happening at school or in activities outside the school, we were surprised by the absence of conditions in schools to provide emergency care to such students.

ConclusionDespite the high prevalence of allergic diseases in childhood, asthmatic children's parents/caregivers, elementary school teachers and university students have inadequate levels of knowledge to monitor these patients.

According to the World Health Organization, allergic diseases are the sixth most common group of childhood diseases and represent one-third of all paediatric chronic illnesses.1,2 Besides health-related deficiencies, allergic diseases have a significant impact on children's daily life, particularly at school, leading to school absenteeism, reduced participation in sporting activities, diminished ability to concentrate, poor school performance, as well as stigmatisation and social exclusion.3

Among allergic diseases, asthma is one of the main reasons for seeking primary care, and it has been reported to cause over 13 million lost school days/year, compromising the development and acquisition of new knowledge and skills while performing school tasks.2–5

The prevalence of food allergies (FA) is estimated at 4–7%. These allergies predominantly appear during the first year of life, although they may manifest at any age, depending on the specific food to which the child becomes allergic. Clinical manifestations of FA are diverse, and they may occur at school if the child is exposed, accidentally or not, to the food to which she is allergic. The reactions may be very intense or even manifest as anaphylactic reactions in some cases.2,5

Anaphylactic reactions are severe and potentially fatal allergic reactions. It is estimated that 82% of all anaphylactic reactions occur at school age, the main aetiological agents being food and hymenoptera insect stings.5,6

As children stay at school for hours each day, it is vital that the environment to which they are exposed is well known, particularly if they are allergic.5 Evidence indicates that the professionals working at schools have insufficient knowledge about the negative impact of allergic diseases on the life of children and their relatives.7,8 Furthermore, most educational centres lack health professionals among their staff, the responsibility of caring for and supervising allergic children during acute episodes at school lies with teachers (9). Along with failures to communicate the child's condition to the school and/or with the lack of an action plan setting out the guidelines of how to proceed in case of emergency, this often puts allergic children at great risk.2,5

Better self-management and knowledge on allergic diseases by both the child and those around her allow a reduction in exacerbations, urgent care, possible hospitalisations and school absenteeism, as well as improving participation in school activities, the child's integration with her peers, and her and her family's quality of life.5,10

Taking this important situation into account, the aim of our study was to assess the level of knowledge on asthma, FA and anaphylaxis among elementary school teachers, parents/caregivers of asthmatic children and university students in the municipality of Uruguaiana, RS, Brazil. The other objective was to evaluate the need to implement joint, complementary action involving families, teachers and health professionals in an attempt to improve the knowledge, training, information and management of allergic diseases in the school environment and in primary care, as well as in universities.

Patients and methodsThe study included 299 university students (US) involved in the health sciences (medicine, nursing, physiotherapy, pharmacy and physical education) at the Federal University of Pampa (Uruguaiana Campus) with ages between 18 and 37 years (average: 30 years old), interviewed randomly. These students were grouped according to the course attended: medicine+nursing+physiotherapy (MNP), and pharmacy+physical education (PPE). All 183 teachers (EST) in Uruguaiana's State elementary school system were invited to take part in the study, 177 of whom actually participated in interviews (81.4% women, 65% over 45 years old). Besides these groups, 111 parents/caregivers (PC) of asthmatic children included in the Program for the Prevention of Childhood Asthma (PIPA)11 (90% women, average age 35 years old) also took part in the study, having been interviewed when entering the program.

All participants answered the Brazilian Portuguese version of the Newcastle Asthma Knowledge Questionnaire (NAKQ),12 which covers knowledge on asthma and has been translated and adapted to Brazilian culture,8 as well as a questionnaire about respondents’ knowledge on FA and anaphylaxis.9

This research has been approved by the local ethics committee, and all students and parents/caregivers agreed to participate and signed a Declaration of Free and Informed Consent after being informed about the objectives of the study.

The answers obtained were transferred to an Excel database by double entry and presented as simple frequencies. Statistical analyses used non-parametric tests with a fixed 5% rejection level for the null hypotheses.

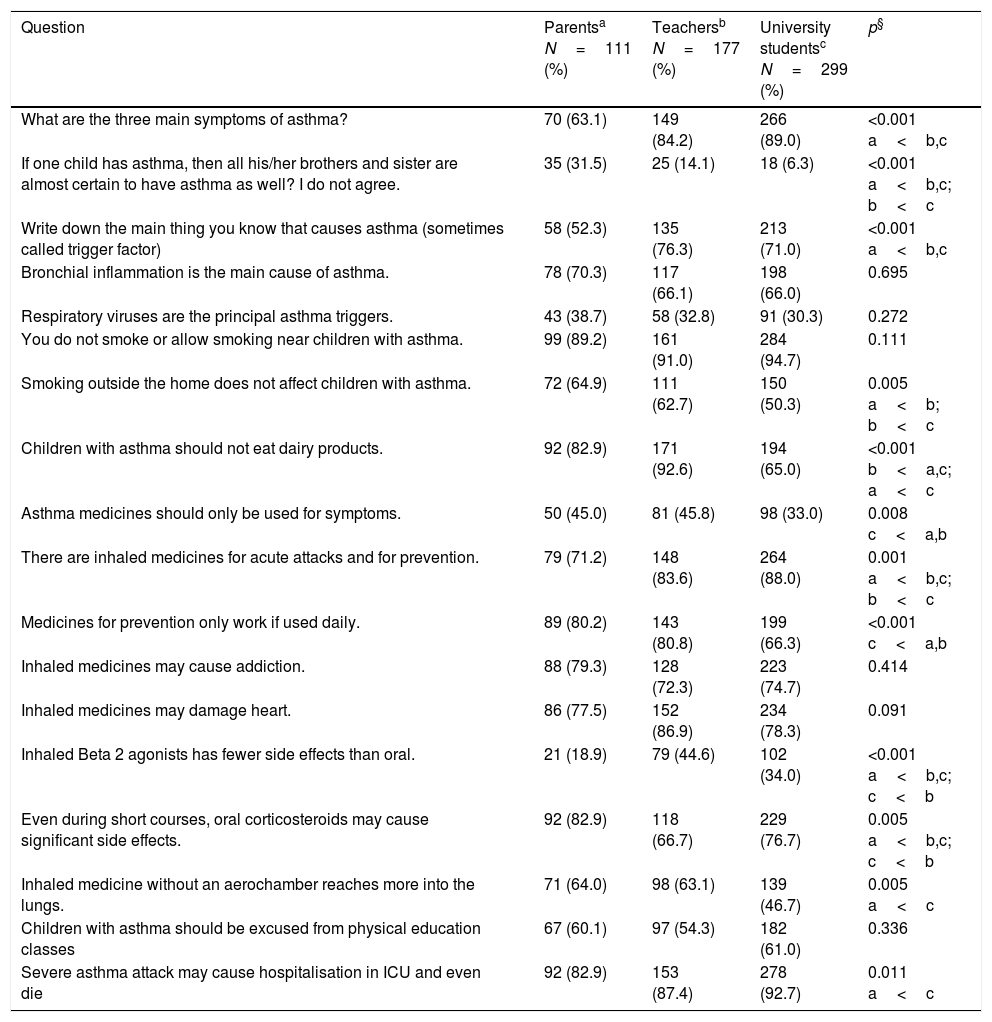

ResultsUniversity studentsNinety percent of the US reported knowing at least one symptom of asthma, 71% named an asthma attack trigger, and 30% recognised the importance of respiratory viruses as asthma triggers (Table 1).

Frequency of affirmative answers about asthma by parents of patients with asthma, elementary school teachers and university students in Uruguaiana, RS, Brazil.

| Question | Parentsa N=111 (%) | Teachersb N=177 (%) | University studentsc N=299 (%) | p§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| What are the three main symptoms of asthma? | 70 (63.1) | 149 (84.2) | 266 (89.0) | <0.001 a<b,c |

| If one child has asthma, then all his/her brothers and sister are almost certain to have asthma as well? I do not agree. | 35 (31.5) | 25 (14.1) | 18 (6.3) | <0.001 a<b,c; b<c |

| Write down the main thing you know that causes asthma (sometimes called trigger factor) | 58 (52.3) | 135 (76.3) | 213 (71.0) | <0.001 a<b,c |

| Bronchial inflammation is the main cause of asthma. | 78 (70.3) | 117 (66.1) | 198 (66.0) | 0.695 |

| Respiratory viruses are the principal asthma triggers. | 43 (38.7) | 58 (32.8) | 91 (30.3) | 0.272 |

| You do not smoke or allow smoking near children with asthma. | 99 (89.2) | 161 (91.0) | 284 (94.7) | 0.111 |

| Smoking outside the home does not affect children with asthma. | 72 (64.9) | 111 (62.7) | 150 (50.3) | 0.005 a<b; b<c |

| Children with asthma should not eat dairy products. | 92 (82.9) | 171 (92.6) | 194 (65.0) | <0.001 b<a,c; a<c |

| Asthma medicines should only be used for symptoms. | 50 (45.0) | 81 (45.8) | 98 (33.0) | 0.008 c<a,b |

| There are inhaled medicines for acute attacks and for prevention. | 79 (71.2) | 148 (83.6) | 264 (88.0) | 0.001 a<b,c; b<c |

| Medicines for prevention only work if used daily. | 89 (80.2) | 143 (80.8) | 199 (66.3) | <0.001 c<a,b |

| Inhaled medicines may cause addiction. | 88 (79.3) | 128 (72.3) | 223 (74.7) | 0.414 |

| Inhaled medicines may damage heart. | 86 (77.5) | 152 (86.9) | 234 (78.3) | 0.091 |

| Inhaled Beta 2 agonists has fewer side effects than oral. | 21 (18.9) | 79 (44.6) | 102 (34.0) | <0.001 a<b,c; c<b |

| Even during short courses, oral corticosteroids may cause significant side effects. | 92 (82.9) | 118 (66.7) | 229 (76.7) | 0.005 a<b,c; c<b |

| Inhaled medicine without an aerochamber reaches more into the lungs. | 71 (64.0) | 98 (63.1) | 139 (46.7) | 0.005 a<c |

| Children with asthma should be excused from physical education classes | 67 (60.1) | 97 (54.3) | 182 (61.0) | 0.336 |

| Severe asthma attack may cause hospitalisation in ICU and even die | 92 (82.9) | 153 (87.4) | 278 (92.7) | 0.011 a<c |

Almost all US (94%) acknowledged that one should not smoke in the presence of an asthmatic child, but half of them think that smoking outside the home would not harm the child and 65% considered that asthmatic children should not consume dairy products (Table 1).

Although 88% of the US knew about the existence of medications for asthma attacks and maintenance, 33% of them believe medications should be used only when there are symptoms, while 66% said preventive drugs should be used daily (Table 1).

Seventy-five percent of the US believe that inhaled beta 2 agonists may cause addiction, 78% think they may cause health problems, and only 34% thought inhaled drugs cause fewer adverse effects than other alternatives. 47% of them believe the use of a valved holding chamber makes it more difficult for drugs to reach the lung (Table 1).

It should be highlighted that 61% of the US believe physical activities should be avoided by asthmatic children, and 93% believe that asthma attacks may be very severe, leading to hospitalisation and even death (Table 1).

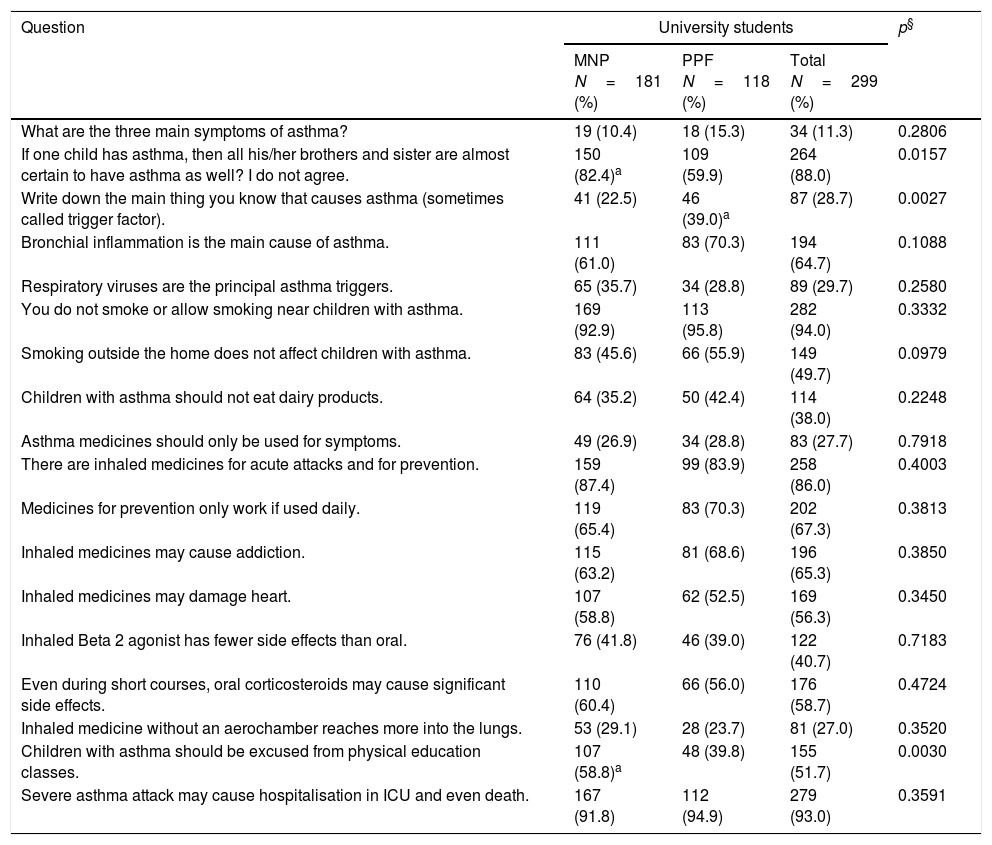

The comparative analysis of US based on their courses (MNP vs. PPE) has shown that a significantly higher number of MNP students (82.4% vs. 39.0%, respectively) stated they do not believe that the siblings of an asthmatic child will also develop asthma. PPE also show a significantly greater lack of knowledge of the aetiological agents of asthma (22.5% vs. 39.0%, respectively) (Table 2).

University students according to their course and answers to the asthma knowledge questionnaire.

| Question | University students | p§ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNP N=181 (%) | PPF N=118 (%) | Total N=299 (%) | ||

| What are the three main symptoms of asthma? | 19 (10.4) | 18 (15.3) | 34 (11.3) | 0.2806 |

| If one child has asthma, then all his/her brothers and sister are almost certain to have asthma as well? I do not agree. | 150 (82.4)a | 109 (59.9) | 264 (88.0) | 0.0157 |

| Write down the main thing you know that causes asthma (sometimes called trigger factor). | 41 (22.5) | 46 (39.0)a | 87 (28.7) | 0.0027 |

| Bronchial inflammation is the main cause of asthma. | 111 (61.0) | 83 (70.3) | 194 (64.7) | 0.1088 |

| Respiratory viruses are the principal asthma triggers. | 65 (35.7) | 34 (28.8) | 89 (29.7) | 0.2580 |

| You do not smoke or allow smoking near children with asthma. | 169 (92.9) | 113 (95.8) | 282 (94.0) | 0.3332 |

| Smoking outside the home does not affect children with asthma. | 83 (45.6) | 66 (55.9) | 149 (49.7) | 0.0979 |

| Children with asthma should not eat dairy products. | 64 (35.2) | 50 (42.4) | 114 (38.0) | 0.2248 |

| Asthma medicines should only be used for symptoms. | 49 (26.9) | 34 (28.8) | 83 (27.7) | 0.7918 |

| There are inhaled medicines for acute attacks and for prevention. | 159 (87.4) | 99 (83.9) | 258 (86.0) | 0.4003 |

| Medicines for prevention only work if used daily. | 119 (65.4) | 83 (70.3) | 202 (67.3) | 0.3813 |

| Inhaled medicines may cause addiction. | 115 (63.2) | 81 (68.6) | 196 (65.3) | 0.3850 |

| Inhaled medicines may damage heart. | 107 (58.8) | 62 (52.5) | 169 (56.3) | 0.3450 |

| Inhaled Beta 2 agonist has fewer side effects than oral. | 76 (41.8) | 46 (39.0) | 122 (40.7) | 0.7183 |

| Even during short courses, oral corticosteroids may cause significant side effects. | 110 (60.4) | 66 (56.0) | 176 (58.7) | 0.4724 |

| Inhaled medicine without an aerochamber reaches more into the lungs. | 53 (29.1) | 28 (23.7) | 81 (27.0) | 0.3520 |

| Children with asthma should be excused from physical education classes. | 107 (58.8)a | 48 (39.8) | 155 (51.7) | 0.0030 |

| Severe asthma attack may cause hospitalisation in ICU and even death. | 167 (91.8) | 112 (94.9) | 279 (93.0) | 0.3591 |

MNP – medicine+nursery+physiotherapy; PPE – pharmacy+physical education.

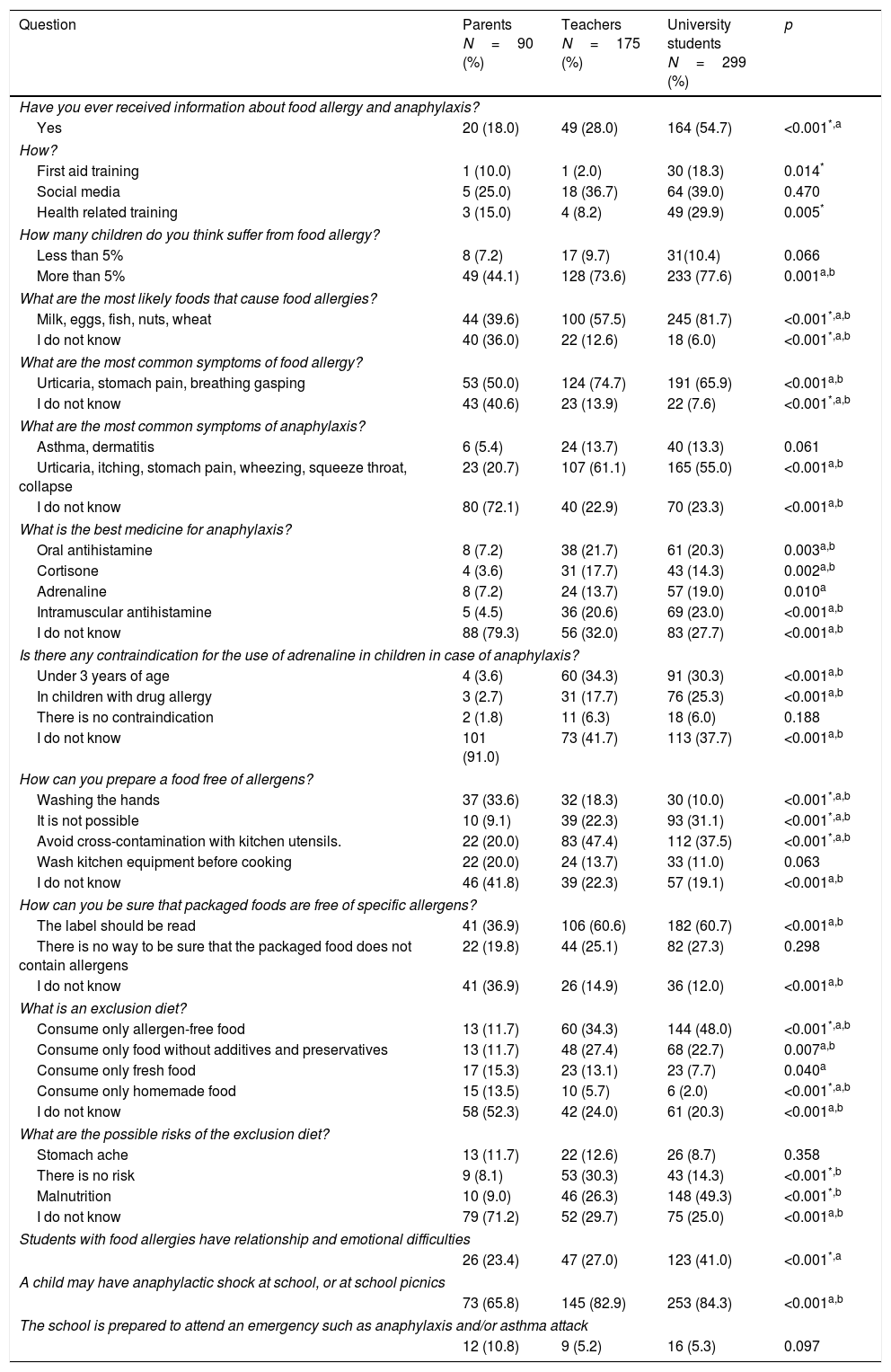

Regarding knowledge on FA and anaphylaxis, only 54.7% of the US reported having received information about these diseases at any moment in the past (Table 3).

Frequency of affirmative answers about food allergy and anaphylaxis by parents of patients with asthma, elementary school teachers and university students in Uruguaiana, RS, Brazil.

| Question | Parents N=90 (%) | Teachers N=175 (%) | University students N=299 (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you ever received information about food allergy and anaphylaxis? | ||||

| Yes | 20 (18.0) | 49 (28.0) | 164 (54.7) | <0.001*,a |

| How? | ||||

| First aid training | 1 (10.0) | 1 (2.0) | 30 (18.3) | 0.014* |

| Social media | 5 (25.0) | 18 (36.7) | 64 (39.0) | 0.470 |

| Health related training | 3 (15.0) | 4 (8.2) | 49 (29.9) | 0.005* |

| How many children do you think suffer from food allergy? | ||||

| Less than 5% | 8 (7.2) | 17 (9.7) | 31(10.4) | 0.066 |

| More than 5% | 49 (44.1) | 128 (73.6) | 233 (77.6) | 0.001a,b |

| What are the most likely foods that cause food allergies? | ||||

| Milk, eggs, fish, nuts, wheat | 44 (39.6) | 100 (57.5) | 245 (81.7) | <0.001*,a,b |

| I do not know | 40 (36.0) | 22 (12.6) | 18 (6.0) | <0.001*,a,b |

| What are the most common symptoms of food allergy? | ||||

| Urticaria, stomach pain, breathing gasping | 53 (50.0) | 124 (74.7) | 191 (65.9) | <0.001a,b |

| I do not know | 43 (40.6) | 23 (13.9) | 22 (7.6) | <0.001*,a,b |

| What are the most common symptoms of anaphylaxis? | ||||

| Asthma, dermatitis | 6 (5.4) | 24 (13.7) | 40 (13.3) | 0.061 |

| Urticaria, itching, stomach pain, wheezing, squeeze throat, collapse | 23 (20.7) | 107 (61.1) | 165 (55.0) | <0.001a,b |

| I do not know | 80 (72.1) | 40 (22.9) | 70 (23.3) | <0.001a,b |

| What is the best medicine for anaphylaxis? | ||||

| Oral antihistamine | 8 (7.2) | 38 (21.7) | 61 (20.3) | 0.003a,b |

| Cortisone | 4 (3.6) | 31 (17.7) | 43 (14.3) | 0.002a,b |

| Adrenaline | 8 (7.2) | 24 (13.7) | 57 (19.0) | 0.010a |

| Intramuscular antihistamine | 5 (4.5) | 36 (20.6) | 69 (23.0) | <0.001a,b |

| I do not know | 88 (79.3) | 56 (32.0) | 83 (27.7) | <0.001a,b |

| Is there any contraindication for the use of adrenaline in children in case of anaphylaxis? | ||||

| Under 3 years of age | 4 (3.6) | 60 (34.3) | 91 (30.3) | <0.001a,b |

| In children with drug allergy | 3 (2.7) | 31 (17.7) | 76 (25.3) | <0.001a,b |

| There is no contraindication | 2 (1.8) | 11 (6.3) | 18 (6.0) | 0.188 |

| I do not know | 101 (91.0) | 73 (41.7) | 113 (37.7) | <0.001a,b |

| How can you prepare a food free of allergens? | ||||

| Washing the hands | 37 (33.6) | 32 (18.3) | 30 (10.0) | <0.001*,a,b |

| It is not possible | 10 (9.1) | 39 (22.3) | 93 (31.1) | <0.001*,a,b |

| Avoid cross-contamination with kitchen utensils. | 22 (20.0) | 83 (47.4) | 112 (37.5) | <0.001*,a,b |

| Wash kitchen equipment before cooking | 22 (20.0) | 24 (13.7) | 33 (11.0) | 0.063 |

| I do not know | 46 (41.8) | 39 (22.3) | 57 (19.1) | <0.001a,b |

| How can you be sure that packaged foods are free of specific allergens? | ||||

| The label should be read | 41 (36.9) | 106 (60.6) | 182 (60.7) | <0.001a,b |

| There is no way to be sure that the packaged food does not contain allergens | 22 (19.8) | 44 (25.1) | 82 (27.3) | 0.298 |

| I do not know | 41 (36.9) | 26 (14.9) | 36 (12.0) | <0.001a,b |

| What is an exclusion diet? | ||||

| Consume only allergen-free food | 13 (11.7) | 60 (34.3) | 144 (48.0) | <0.001*,a,b |

| Consume only food without additives and preservatives | 13 (11.7) | 48 (27.4) | 68 (22.7) | 0.007a,b |

| Consume only fresh food | 17 (15.3) | 23 (13.1) | 23 (7.7) | 0.040a |

| Consume only homemade food | 15 (13.5) | 10 (5.7) | 6 (2.0) | <0.001*,a,b |

| I do not know | 58 (52.3) | 42 (24.0) | 61 (20.3) | <0.001a,b |

| What are the possible risks of the exclusion diet? | ||||

| Stomach ache | 13 (11.7) | 22 (12.6) | 26 (8.7) | 0.358 |

| There is no risk | 9 (8.1) | 53 (30.3) | 43 (14.3) | <0.001*,b |

| Malnutrition | 10 (9.0) | 46 (26.3) | 148 (49.3) | <0.001*,b |

| I do not know | 79 (71.2) | 52 (29.7) | 75 (25.0) | <0.001a,b |

| Students with food allergies have relationship and emotional difficulties | ||||

| 26 (23.4) | 47 (27.0) | 123 (41.0) | <0.001*,a | |

| A child may have anaphylactic shock at school, or at school picnics | ||||

| 73 (65.8) | 145 (82.9) | 253 (84.3) | <0.001a,b | |

| The school is prepared to attend an emergency such as anaphylaxis and/or asthma attack | ||||

| 12 (10.8) | 9 (5.2) | 16 (5.3) | 0.097 | |

Eighty-one percent (81%) of US recognised that food might provoke FA; 65.9% correctly named the most frequent symptoms of FA and 55% named those of anaphylaxis. Only 19% of the students indicated adrenaline as the drug of choice for treating anaphylaxis, and 37.7% could not say whether there were any contraindications to adrenaline use in children for treating anaphylaxis (Table 3).

Although 31.1% of the US think it is impossible to have an allergen-free diet, 60.7% of them recognise labels as a safe way to know whether packaged food is allergen free. Forty-eight percent (48%) of them know what an elimination diet is, but 25% do not know whether they may pose any health risks (Table 3).

Only 41% of the US believe that children with FA may have emotional or relationship problems, but 84.3% recognised that these children might suffer an anaphylactic reaction at school, and only 5.3% believe the school is prepared to deal with this type of emergency (Table 3).

TeachersEighty-four percent (84%) of EST identified at least one sign of asthma, 76% identified one trigger of asthma attacks, 32% identified viruses as triggers, and only 14% believed all siblings of an asthmatic child would also develop asthma (Table 1).

Ninety-one percent of the EST recommended not smoking close to an asthmatic child, but 62% of them believed that smoking outside the home would not affect the health of children with asthma. It caught our attention that 92% of the EST believed children should avoid dairy products. We were also surprised that while over 83% of them know about the existence of medications for treating asthma attacks and for asthma maintenance, a little over 45% of them believed treatment should be done only when a child shows symptoms of the disease (Table 1).

Although 80% of the EST believe preventive medications should be used daily, 72% of them think inhalers may cause addiction, 86% of them believe these medications may affect the heart, 63% said that using a valved holding chamber would not improve drugs’ access to the lungs and 66% believe that oral corticosteroids may cause severe side effects even if used for a short period (Table 1).

For 54% of EST, physical activities should be suspended for asthmatic children, and 87% consider that severe attacks may lead to hospitalisation or even death (Table 1).

Only 28% of the EST reported having received any information on FA and anaphylaxis (Table 3). Although 74.7% of the EST know the most frequent symptoms of FA, only 57.5% identified the food items most often involved in FA. Only 23% did not know the symptoms of anaphylaxis. However, only 13.7% of the teachers identified adrenaline as the drug of choice for treating anaphylactic reactions, and 41.7% were not aware of any contraindication to its use for treating children (Table 3).

Only 47.4% of the teachers reported they knew how an allergen-free diet should be prepared, and 30%, a significant proportion of the teachers, did not know the risks of using this type of diet, while 60.6% considered it important to read food labels before offering them to children with FA (Table 3).

Only 27% of the EST recognised that children and adolescents with FA may suffer emotional and relationship difficulties, and while 82% of responding teachers know that a child may have an anaphylactic reaction at school or during outdoor activities outside the school, only 5.2% of them considered the school would be prepared to deal with such an emergency (Table 3).

Parents/caregiversAlthough the children under the care of the PC interviewed here have respiratory diseases, only 63% of them could identify a symptom of asthma, 35% believe if one child is asthmatic, their siblings will also develop the disease, and a little over half of them could point out possible triggers of asthma attacks. Only one-third of them reported respiratory viruses as triggers of asthma episodes, and surprisingly, 83% of responding PC believe asthmatic children should not consume dairy products (Table 1).

Remarkably, while 90% of the PC recognise one should not smoke in the presence of asthmatic patients, 65% of them believe smoking outside the home would not be harmful (Table 1).

It is surprising that 45% of responding PC believe asthma should only be treated when symptoms are present, although 80% of them answered that asthma control medications should be used daily (Table 1).

Seventy-five percent of the PC believe inhaled medications cause addiction and may affect users’ hearts, which is reinforced by the small percentage (19%) of parents who considered inhaled medications to be safer. Eighty-two percent of PC believe that oral corticosteroids may cause side effects even if used for a short time (Table 1).

We were surprised that 60% of PC believed the physical activities of children under their care should be suspended, and over 82% fear that an acute asthma attack may lead to death (Table 1).

Eighty-two percent of asthmatic children's PC reported they had never received any information about FA and anaphylaxis (Table 3). Thirty-six percent of them did not know the food items that may provoke FA, 50% recognised the most frequent symptoms of FA, while only 20.7% knew those of anaphylaxis. 79.3% of the PC do not know what the medication of choice to use in an anaphylactic shock would be, and 91% could not say whether there are any contraindications for using adrenaline to treat anaphylactic reactions in children (Table 1).

Forty-two percent (42%) of the PC did not know how to prepare an allergen-free diet, 37% did not know how to recognise packaged foods free from specific allergens, 52.3% do not know what an elimination diet is, and 71.2% do not know whether such a diet might pose any risks (Table 3).

Only 23.4% of PC think children with FA may go through any emotional or relationship difficulties. Despite the low knowledge of PC on anaphylaxis, 65.8% of them believe children with FA may have an anaphylactic shock while at school, and only 10.8% of them believe the school would be prepared to help these children (Table 3).

DiscussionIn this study, we found that, despite the high prevalence of allergic diseases, our respondents have insufficient knowledge on them. These results are highly relevant, as incorrect knowledge and attitudes when dealing with allergic children may influence their quality of life5 and their relations with their peers.3 Adequate health care for such children based on the control of allergic diseases should allow for maximum reduction of the negative impact of these diseases on their future life.13

It is a known fact that children spend a large part of their time at school, especially inside the classroom, under the supervision and care of teachers.14 This makes these professionals the first in line to help students during an acute allergic episode. However, similarly to other authors,7,8,15 we document here that our responding EST have insufficient knowledge of asthma, food allergies, and anaphylaxis. Only a third of them recognised the role of respiratory viruses as a trigger of asthma attacks,16 and most wrongly believe that asthmatic children should avoid dairy products – a result similar to that found in the beliefs of PC and US (Table 1).

Another worrying fact is that two-thirds of EST believe smoking outside the home would not affect asthmatic children, thus showing a lack of knowledge about the important role of second- and third-hand smoke in respiratory disease exacerbations.17 This possibly reflects the lack of an anti-tobacco policy in schools,18,19 as recommended by the World Health Organization.20 However, since this fact is also mostly unknown to PC and US despite the existence of many anti-tobacco actions,18–21 we believe these campaigns are not sufficient for target audiences to properly understand tobacco impacts on respiratory diseases and health in general.22,23

Questionnaires assessing the level of the respondents’ knowledge on allergic diseases fundamentally address knowledge and “myths” that must be taken into consideration since, despite their education, people are influenced by sometimes deeply entrenched beliefs, provoking negative impacts on adherence to the treatment recommended to patients.24

Respondents’ knowledge about the drugs used for asthma treatment was surprisingly low, especially with regard to their formula, form of administration and side effects. Resistance to drug use is made evident in our study, as most respondents considered that inhaled drugs might cause addiction or affect patients’ hearts. There is also a lack of knowledge or acceptance that the use of inhaled drugs with a valved holding chamber would improve drug access to the lungs, as also seen in studies by other authors.15,25,26 In a way, these factors contribute to the lack of patient adherence to treatment, and consequently to worse asthma control.

Fears related to drug use or that an acute asthma attack may evolve to death were reported by a significant proportion of PC. If these “fears” are not shared with health professionals, they may also lead to increased stress and depression in the family environment,27 which may in turn lead parents and caretakers to impose exaggerated limitations on children's lives, maybe even causing adolescent alexithymia or depression,28 all associated with a reduced trust by the asthmatic patient and her family in their ability to control the disease.29

The lack of knowledge on asthma may also cause social marginalisation at school due to the exclusion of asthmatic children from social and sports activities, as reported by all groups assessed here. Physical inactivity in asthmatic patients is related to a more sedentary lifestyle and obesity.30 Praena-Crespo et al. observed that asthmatic children who participated in an educational program on Asthma, Sports and Health in elementary schools improved not only their knowledge about the disease but also their quality of life, self-esteem, emotional aspects and integration in school activities.31

This social exclusion due to a lack of knowledge about pulmonary health and the evolution and monitoring of the disease by teachers, peers, and professionals, in general, may cause asthmatic children to become the victims of bullying and cyber bullying,32 exposing them to the risks that victimised children may suffer in the future, such as psychiatric disorders and suicidal tendencies as adults.33,34

Knowledge on FA and anaphylaxis was low in all three groups assessed. Although the symptoms of FA may first appear at school due to involuntary exposure to a food to which a child is sensitive,35 few of our respondent EST recognised the symptoms of FA and anaphylaxis or knew how to act in an emergency.9

FAs also have a large impact on the emotional well-being of affected children and families.36,37 The control of FA requires children to know and keep a constant vigilance of allergens that should be avoided in their diet. This may generate stress for parents when a child first starts her scholar activities, as they worry about whether school cafeteria staff have adequate knowledge of FAs and the possibility of cross-contamination,27 or about whether the school knows the existence of the Brazilian federal law ensuring that special school lunch should be made available for students with dietary restrictions (Federal Law # 12.982/14 of May 28th, 2014, Brazil).38

This fear is not an exaggeration, as the necessary care regarding elimination diets, their preparation and the possible complications in their use were also not well known by responding PC and US, which shows a need for better information on allergy care directed not only to allergic children's parents and caretakers, but also to teachers, cooks, school staff and all professionals who will work in primary care in the future.39

Increasing evidence suggests that FA may make children more vulnerable to situations like social ostracism or bullying at school.40 Shemesh et al. refer that 31.5% of children with FA aged 8–17 reported having been intimidated due to their allergy, and that 80% of those indicated a classmate as the bully threatening them by offering forbidden food or making verbal jokes.41 This is alarming, considering the long time these children spend together at school.

According to Lieberman et al., 80% of all bullying episodes occur at school, and 21% of bullied children were intimidated by teachers or school staff.42 According to Muraro et al., children with FA are twice as likely to be intimidated by their non-allergic peers43 and show important levels of alexithymia.44 These authors recommend that these children and their families receive adequate psychological support, particularly those who have already had a severe anaphylactic reaction.45

Despite this reality, we found that only 27% of responding EST recognised that children and adolescents with FA might suffer emotional or relationship difficulties. These are alarming data, for if teachers are not aware of the existence of bullying or the potential severity of FAs, or if parents warn the school on this subject and are not heeded,46 FA-related bullying will continue to occur, generating unnecessary stress and anxiety to these children and placing them in a potentially dangerous situation.47

Considering that the symptoms of an allergic reaction usually appear very rapidly, usually between 5 and 30min after exposure to the allergen, it is essential that those involved with allergic children know how to recognise reactions and how to readily treat them if necessary.39

Therefore, it is expected that schools be responsible for implementing an emergency care policy and a policy for preventing exacerbations and that their employees recognise severe reactions and participate in the procedures to be done when faced with one in an organised way.2 This is very important, as only 13% of responding EST identified adrenaline as the drug of choice for treating anaphylaxis, and only 58.3% of them know whether there are contraindications to adrenaline use in children, results similar to those published recently by other authors.48

Although most of our respondents are aware that a child may have an anaphylactic reaction at school or during educational activities outside the school, only a minority of them believe that the school is prepared to deal with this type of emergency.

We feel that what is shown above is enough justification to state that this is an alarming situation. Schools are not a safe place for children or adolescents with asthma or food allergies, and this is not exclusively a Brazilian problem, as many authors have been warning over the years.2,5,7,9,49

In order to remedy this situation, efforts must be exerted on many fronts to improve primary care. Papadopoulos et al. alert to the important fact that although 90% of children and adolescents should receive adequate treatment in primary care, this does not happen, largely due to deficient education on asthma and allergic diseases in general during undergraduate studies.50 This education in the early stages of college education would avoid knowledge gaps such as those found in responding university students here.

Several studies have addressed the importance of a stronger relationship between families, school and health professionals in order to ensure that this problem is handled with adequate collaboration by multidisciplinary teams, in a similar way to that used in successful experiences like Integrated Care Pathways for Airway Diseases (AIRWAYS-ICPs),51 in which doctors, nurses, pharmacists, physiotherapists and physical education teachers work in an integrated manner with families, schools, and the community.

The care of allergic children in school is a social issue needing coordinated efforts by school staff, health professionals, families, the community, and also the competent government authorities. It is necessary to create standardised guidelines to care for allergic children in schools, and also to provide adequate and continuous training to all the professionals involved in caring for these children, so that they may enjoy the quality of life they deserve.52

Conflict of interestNone.