Quality of sleep is essential for physical and mental health and influences the perception of the patient's well-being during the day. In patients with chronic allergic diseases sleep disorders may increase the severity of the condition, complicate the management and impair their quality of life. When children are concerned, their parents are also affected by the problem. We evaluated the presence of disrupted sleep in parents of children with atopic disorders, and its relationship with clinical features and the presence of disturbed sleep in children.

MethodsParents of children suffering from allergic diseases were recruited from the Pediatric Allergy Units of Parma University. Evaluation of sleep in parents was based on the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), while in children it was based on the Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC).

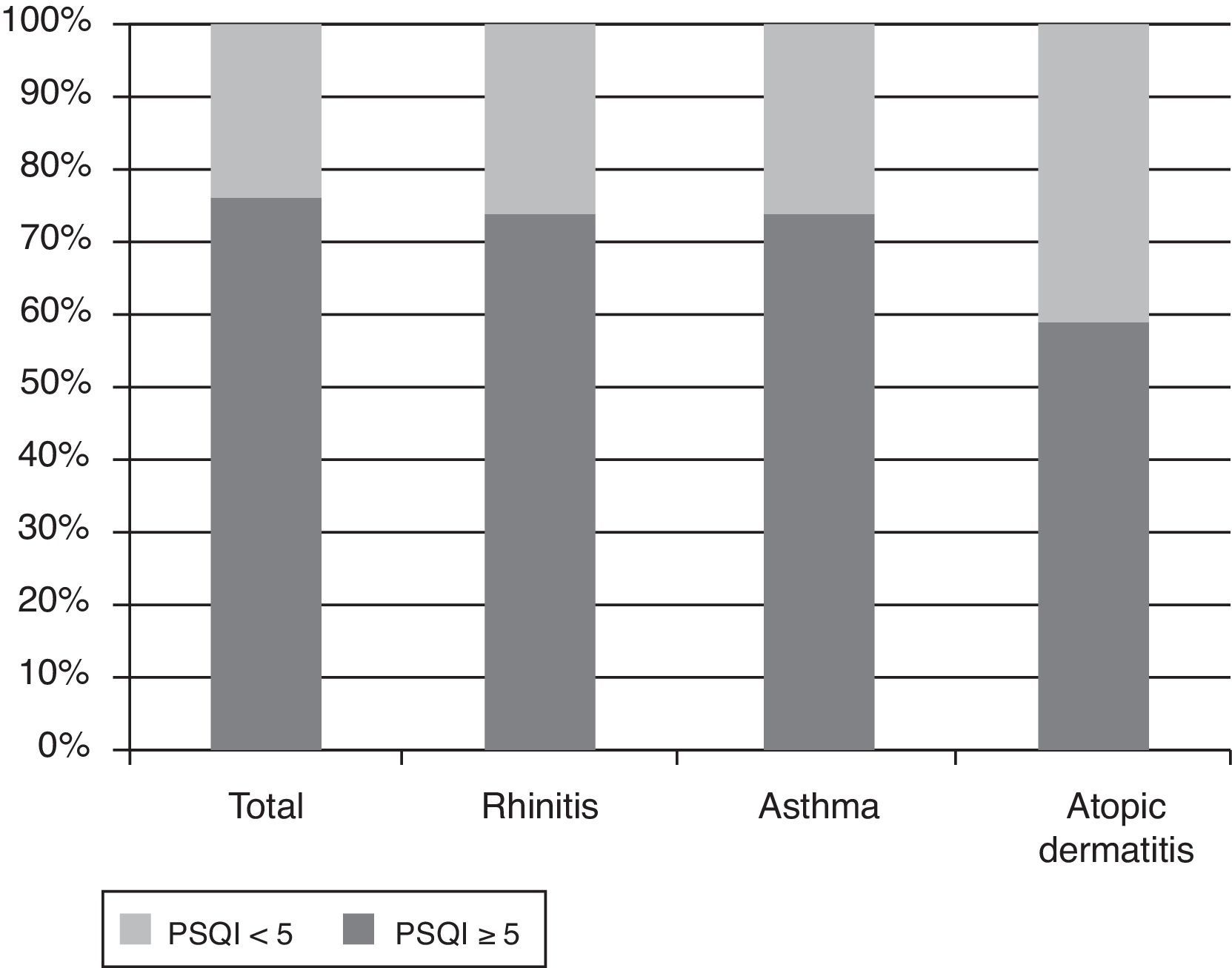

ResultsOf the 102 parents invited, 92 filled in the questionnaire. Only the questionnaires with more than a 95% completion rate were considered for analysis. PSQI mean score in parents was 6.6 (SD 2.6); 75.6% of them had a PSQI≥5, indicating that most parents had a sleep quality perceived as bad. The PSQI≥5 was more common in parents of children with asthma and rhinitis. In children, SDSC mean score was 42.1 (SD: 9.4); 62.3% had a total score≥39. The quality of sleep in parents and children was significantly correlated (p<0.001).

ConclusionThese findings make it apparent that an alteration of sleep in children can also affect the parents. Such effect further weighs the burden of respiratory allergy and needs to be considered in future studies.

Quality of sleep is essential for physical and mental health and influences the perception of the patient's well-being during the day. In patients with chronic allergic diseases, including asthma, rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis, sleep disorders may increase the severity of the condition, complicate the management by the physician and adversely affect the quality of life and mood. The resulting impairments in performance of common daily activities affect both children and adults and generate social and health care costs.1

The causes of sleep disturbances in allergic diseases are numerous and many of these are also frequent in the general population (circadian rhythm disturbance, insufficient or ineffective sleep, inadequate sleep hygiene).2

Sleep quality may be altered in patients with respiratory allergy. Sleep impairment is common in allergic rhinitis, particularly in more severe forms.3 Allergic rhinitis is a risk factor for “sleep disordered breathing” in children.4 This term describes a large spectrum of abnormal respiration during sleep, ranging from primary snoring to obstructive sleep apnoea. Snoring time is in fact higher during the pollen season in subjects with allergic rhinitis.5 In asthmatic patients nocturnal symptoms such as cough, wheezing and breathlessness may disrupt sleep quality. In children with wheezing, sleep quality is more frequently impaired than in children without wheezing due to difficulty in falling asleep, restless sleep and snoring.6

It should also be considered that some anti-allergic drugs, such as sedating antihistamines, can alter sleep due to their effect on the central nervous system.7 Nasal decongestants containing pseudoephedrine are, on the contrary, associated with insomnia.8

Several tools are available to subjectively assess the degree of impairment of sleep in these patients.9 Disease-specific QoL questionnaires are widely used to assess the impact of the disease on health and on sleep as suggested by recommendations from scientific societies.10

In children, the impact of a chronic disease also falls on the parents.11 This impact must be considered with great attention in the management of illness that must be always shared by the parents and children.

The aim of this cross-sectional observational survey was to evaluate the presence of disrupted sleep in the parents of children with atopic disorders, and its relationship with clinical features and the presence of disrupted sleep in children.

Materials and methodsSubjectsParents of children suffering from a allergic disease were recruited in the out-patient clinic of the Pediatric Allergy Units of Parma University between April and October 2010.

In order to be eligible, participants had to be parents of a child suffering from allergic rhinitis, asthma or atopic dermatitis. Parents with chronic diseases themselves were excluded from the study, although pre-existing sleep disorders cannot be ruled out.

After taking the clinical history, all children underwent physical examination and skin prick tests for common aeroallergens and foods. Asthmatic children also underwent spirometry.

Two written questionnaires, the Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC)12 and the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI),13 were administered during the first visit of the child to the hospital, in order to asses sleep parameters in children and their impact on quality of sleep in parents, respectively.

Evaluation of sleep qualityEvaluation of sleep in parents was based on the PSQI, which is a self-administered, 23-item questionnaire that evaluates sleep quality and quantity. PSQI yields a seven components score: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, duration, habitual sleep efficacy, sleep disturbance, use of sleeping medication and daytime dysfunction. As the score increases, sleep quality decreases and daytime dysfunction due to sleep disorder increases. The PSQI total score was calculated by adding the seven component score together (range between 0 and 21). A PSQI score greater than 5 reaches a diagnostic sensitivity of 89.6% and specificity of 86.5% in distinguishing good and poor sleepers.13

Evaluation of sleep in children was based on SDSC, which is a 26-item instrument for evaluating sleep among children aged 3–18 years. It differentiates among conditions, such as disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep, sleep breathing disorders, disorders of arousal, sleep–wake transition disorders, excessive somnolence, and sleep hyperhydrosis, which represent the most common areas of sleep disorders in children and adolescents. Higher scores indicate greater sleep disturbance, and a score of 39 has been established as the clinical cut-off.12

Both questionnaires are validated on the Italian population.

Evaluation of diseases severityDiagnoses and severity of rhinitis, asthma and atopic dermatitis were defined according to Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA),14 Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA)15 and Scoring Atopic dermatitis (SCORAD).16 In particular, rhinitis was classified as mild intermittent, mild persistent, moderate/severe intermittent and moderate/severe persistent; asthma was classified as intermittent, mild persistent, moderate persistent and severe persistent; atopic dermatitis was classified as mild, moderate and severe.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed by SPSS computer program. Comparison of the variables was performed with the Chi-square test. Pearson's correlation analysis was performed for the correlations. P values less than 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

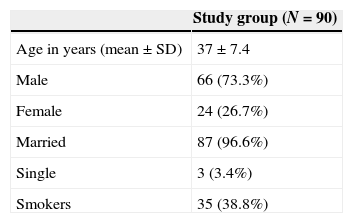

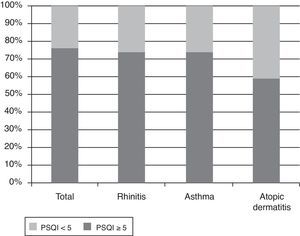

ResultsOf the 102 parents invited, 92 filled in the questionnaire. Only the 90 questionnaires with more than a 95% completion rate were considered for analysis. Parents’ demographic characteristics are provided in Table 1. Study results are presented in Tables 3 and 4 and in Fig. 1.

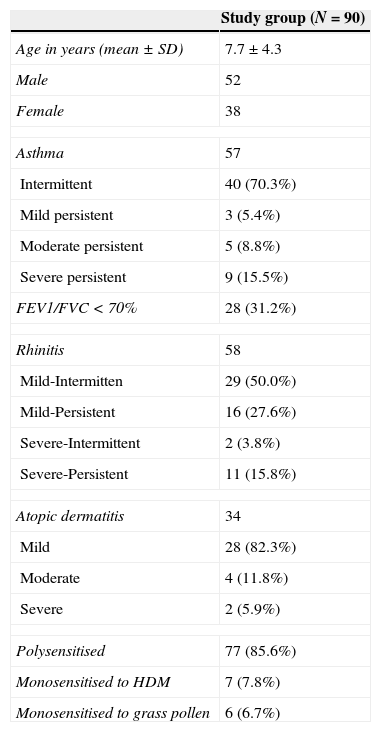

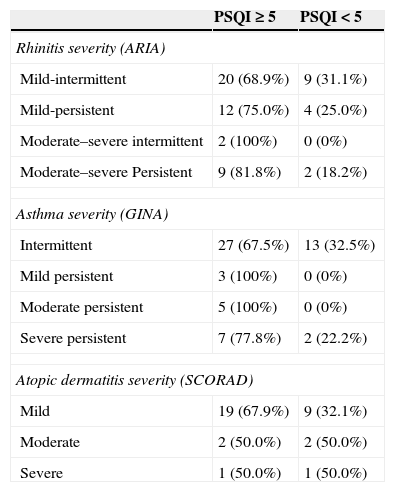

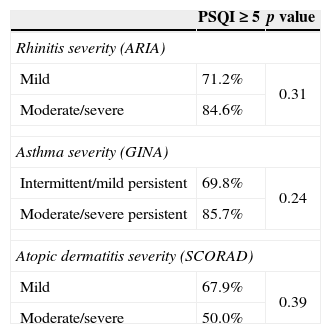

Demographic and allergy-related characteristics of the 90 children are reported in Table 2. PSQI mean score in the group of parents was 6.6 (SD: 2.6, range: 0–13, median: 6). 75.6% of them had a PSQI≥5 and this means that most parents had a subjective sleep quality perceived as bad, while only 24.4% had a good sleep quality perception (PSQI<5). The PSQI≥5 was more common in parents of children with asthma and rhinitis. In fact, if the parents of children with rhinitis and asthma are considered, 74.1% and 73.7% had a PSQI≥5, respectively, while 58.9% of the parents with atopic dermatitis had PSQI≥5 (Fig. 1). The percentages of bad sleepers according to the severity of illness of the child are shown in Table 3. The correlation between PSQI and ARIA, GINA and SCORAD classification of severity showed that moderate-severe diseases in children were not associated with poor sleep quality in parents compared with those with a mild disease (Table 4). The PSQI≥5 was more common in parents of children allergic to dust mites, the most important indoor allergen (p=0.03). Regarding child characteristics, no significant relationship was found between parents of polysensitised children and monosensitised children (p=0.88), or the presence of FEV1/FVC<70% (p=0.42). Additionally, no difference was found in parents of children with only rhinitis and parents of children with concomitant asthma (p=0.08). In children, SDSC mean score was 42.1 (standard deviation: 9.4, range: 22–68, median: 41). Fifty-six of them (62.3%) had a total score≥39. Among the different sleep disorders, the disorders of initiating and maintaining the sleep and the sleep–wake transition disorders were the most altered.

Children's characteristics.

| Study group (N=90) | |

|---|---|

| Age in years (mean±SD) | 7.7±4.3 |

| Male | 52 |

| Female | 38 |

| Asthma | 57 |

| Intermittent | 40 (70.3%) |

| Mild persistent | 3 (5.4%) |

| Moderate persistent | 5 (8.8%) |

| Severe persistent | 9 (15.5%) |

| FEV1/FVC<70% | 28 (31.2%) |

| Rhinitis | 58 |

| Mild-Intermitten | 29 (50.0%) |

| Mild-Persistent | 16 (27.6%) |

| Severe-Intermittent | 2 (3.8%) |

| Severe-Persistent | 11 (15.8%) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 34 |

| Mild | 28 (82.3%) |

| Moderate | 4 (11.8%) |

| Severe | 2 (5.9%) |

| Polysensitised | 77 (85.6%) |

| Monosensitised to HDM | 7 (7.8%) |

| Monosensitised to grass pollen | 6 (6.7%) |

HDM: house dust mites.

Bad sleep quality in parents (PSQI≥5) in ARIA, GINA and SCORAD severity categories of children diseases.

| PSQI≥5 | PSQI<5 | |

|---|---|---|

| Rhinitis severity (ARIA) | ||

| Mild-intermittent | 20 (68.9%) | 9 (31.1%) |

| Mild-persistent | 12 (75.0%) | 4 (25.0%) |

| Moderate–severe intermittent | 2 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| Moderate–severe Persistent | 9 (81.8%) | 2 (18.2%) |

| Asthma severity (GINA) | ||

| Intermittent | 27 (67.5%) | 13 (32.5%) |

| Mild persistent | 3 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| Moderate persistent | 5 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| Severe persistent | 7 (77.8%) | 2 (22.2%) |

| Atopic dermatitis severity (SCORAD) | ||

| Mild | 19 (67.9%) | 9 (32.1%) |

| Moderate | 2 (50.0%) | 2 (50.0%) |

| Severe | 1 (50.0%) | 1 (50.0%) |

Comparison of sleep quality in parents according to severity of the allergic disease in children.

| PSQI≥5 | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Rhinitis severity (ARIA) | ||

| Mild | 71.2% | 0.31 |

| Moderate/severe | 84.6% | |

| Asthma severity (GINA) | ||

| Intermittent/mild persistent | 69.8% | 0.24 |

| Moderate/severe persistent | 85.7% | |

| Atopic dermatitis severity (SCORAD) | ||

| Mild | 67.9% | 0.39 |

| Moderate/severe | 50.0% | |

The PSQI scores of parents were correlated with the quality of sleep in children. In fact, the correlation between PSQI and SDSC was highly significant (p<0.001, r=0.34).

DiscussionThe relationship between atopic diseases, such as asthma, allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis has gained increasing interest concerning both the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying sleep disorders and the burden of sleep impairment on daily activities and quality of life.17 The impact of sleep disorders on patients with respiratory allergy has been emphasized by the international guidelines, namely by GINA for asthma,14 and ARIA for rhinitis,15 which introduced the presence of sleep disturbances as a component of the new classification of these diseases. Quality of sleep in patients with atopic dermatitis can also be significantly impaired by the disease. Both objective measurement of sleep, like actigraphy, and self report measurement, like Quality of Life (QoL) questionnaires, demonstrated that atopic dermatitis patients slept less well and reported more daytime fatigue than controls.18 Sleep loss in these patients is associated with increased itching and decreased QoL.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the presence of sleep disorders in healthy adults who are parents of children with respiratory allergy, while this issue has been previously investigated in parents of children with atopic dermatitis.19

Our results show that sleep is disrupted not only in children with atopic disorders but also in their parents. Sleep disorders are frequent among the general population and about 20–30% of adults suffer from chronic sleep disturbances.20 A large prospective study involving over 2000 adults suffering from allergic rhinitis showed how in more than 50% of the patients with moderate/severe disease the sleep quality was subjectively perceived as bad (PSQI≥5) with an inverse relationship between severity of the disease and sleep quality.3 It is apparent that an alteration of sleep in children can affect the other members of the family. Indeed, the impact of a chronic disease on the caregiver is a central issue when dealing with paediatric patients. In our study, 75% of the parents of allergic children had a disrupted sleep; this was despite the majority of children having a mild disease. The presence of the disease itself may represent a stressful condition that may lead to anxiety in parents21 with consequences on sleep quality. The results of our study show that disrupted sleep in parents seems to be related to the presence of sleep disturbance in children, whereas it appears to be independent of the severity of the child's illness.

Therefore, an adequate treatment of allergic diseases, aimed at reducing the presence of symptoms during the night, may positively yield better quality of sleep also in parents.

When interpreting the results of the current study, some limits should be considered. First, the study was conducted in a single setting and included only a limited number of participants. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the analysis does not allow to draw causal inferences of the determinants of well-being. Moreover, due to the study design, we were unable to control the effect of treatment on the sleep quality of parents and children. However, the effect on parents further weighs the burden of respiratory allergy and needs to be considered in future studies.

Ethical disclosuresPatients’ data protectionThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.