Lepisma saccharina (silverfish) is a common insect which is often found in human dwellings. Our aim was to determine the IgE antibody pattern to this arthropod in children with allergic respiratory symptoms.

MethodsThe individual sera and a pool of selected sera of 45 children with asthma and/or rhinitis were used for an immunoblotting test with an extract of Lepisma saccharina; an immunoblotting inhibition test was performed with extracts of L. saccharina, D. pteronyssinus and cockroach.

ResultsBetween one and ten IgE binding bands were found in the sera of patients. The immunoblotting pattern was clearly different from that of D. pteronyssinus. Inhibition was found with D. pteronyssinus and cockroach, which proves cross-reactivity between extracts.

ConclusionAllergenicity of Lepisma is demonstrated through in vitro tests. A pathogenic role still remains to be proved, but it should be considered in respiratory allergy, due to primary sensitisation to Lepisma, or to cross-reactivity with other indoor allergens.

Lepisma saccharina (silverfish) is a common fusiform insect (http://species.wikimedia.org/wiki/Lepisma_saccharina), about 10-12mm long, with long antennae and long caudal appendages, a body lacking pigmentation, and with greyish dorsal scales that give it a silvery reflection1. It can be very often found in human dwellings, where it finds a warm stable environment, safe from predators, and a ready supply of food (rich in sugars, starch, cellulose, etc.) especially from papers and books.

Inner-city children are commonly exposed to arthropods in their environment2–5, which can result in sensitisation, as often described for cockroaches, even if these go unnoticed. As exposure to silverfish is even more frequent6, we aimed, first, to investigate if there could be an IgE sensitisation to these insects, and second, to study its IgE antibody pattern in children with allergic respiratory symptoms.

MATERIAL AND METHODSWe performed an immunoblotting study with leftover sera of 45 children with allergic respiratory symptoms, who had shown positive responses (wheal diameter ≥ 3mm) in prick tests with the Lepisma extract. The patients were also skin tested with mites (D. pteronyssinus, D. farinae), moulds, common pollens, cat and dog dander, cockroach, and some with other allergens as indicated based on their clinical history: patients with a positive skin prick test and/or a RAST-CAP test > 0.35 kU/L to a given allergen were considered sensitised.

Silverfish extract preparationSilverfish (Lepisma saccharina) was purchased from Central Science Laboratory (Sand Hutton, York, UK) and cultured in Diater Laboratories (Madrid, Spain). The insects were killed by freezing and stored at −80°C. The extract preparation was performed as described by Barletta et al7: briefly, the extract from silverfish insect bodies was prepared by homogenising frozen silverfish in Tris-HCl buffer 100mM pH 8.0; the homogenate was extracted by stirring and centrifuged for 10 minutes. The soluble material was filtered through a 0.22μm Millipore filter, and the insoluble material was resuspended in 100mM Tris pH 10.6. Protein content was measured according to the methods of Bradford8.

IgE antibody studyProteins from silverfish extract were analysed by sodium dodecylsulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), according to Laemmli9 in 15 % polyacrylamide gels under reducing conditions. Proteins were visualised by Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 staining and electrophoretically transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF, Immobilon-P membranes, Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden). The binding of IgE antibody to allergens was analysed by western blot using the individual sera from the patients and anti-human IgE peroxidase conjugate (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA). Chemiluminescence detection reagents (Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus Western lightning. Perkin Elmer) were added following the manufacturer's instructions. IgE binding bands were identified using the BioRad Diversity database program.

The same procedure was used with a pool of 9 selected sera, those of the patients who showed more distinct bands, using the extract of Lepisma and an extract of D. pteronyssinus.

EIA inhibitionSolid-phase antigen was obtained by coupling the extract solution (10mg/ml) to the 6-mm diameter CNBr-activated paper disks by the method of Ceska and Lundqvist10, and EIA was performed as described by Wide et al11 with HY-TEC EIA (Hycor Biomedical, Inc., Irvine, CA, USA). An EIA inhibition test of the Lepisma extract was performed preincubating the pool of sera with extracts of Lepisma, D. pteronyssinus, and cockroach, using concentrations from 0.0025 to 250μg/mL.

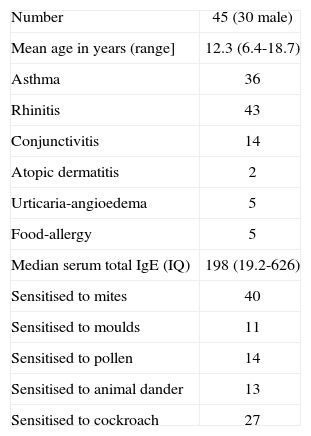

RESULTSThe study group comprised 45 children who had positive skin tests to L. saccharina. All of them had clinical symptoms of asthma (n = 36) and/or rhinitis (n = 43), and some of other diseases, and were 25 % of those tested with the Lepisma extract. A description of the group is shown in Table I.

Description of the study group

| Number | 45 (30 male) |

| Mean age in years (range] | 12.3 (6.4-18.7) |

| Asthma | 36 |

| Rhinitis | 43 |

| Conjunctivitis | 14 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 2 |

| Urticaria-angioedema | 5 |

| Food-allergy | 5 |

| Median serum total IgE (IQ) | 198 (19.2-626) |

| Sensitised to mites | 40 |

| Sensitised to moulds | 11 |

| Sensitised to pollen | 14 |

| Sensitised to animal dander | 13 |

| Sensitised to cockroach | 27 |

IQ: interquartile range

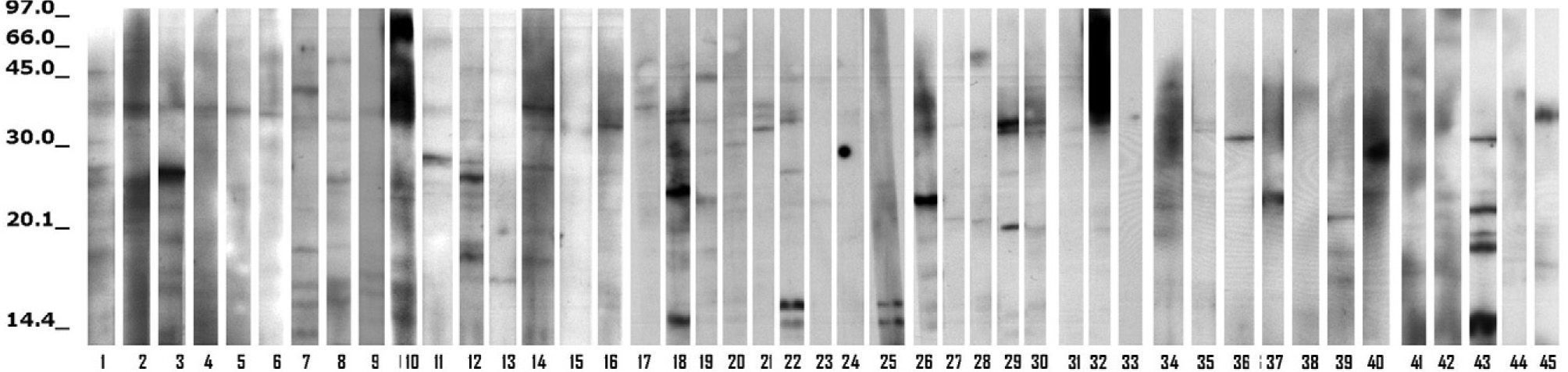

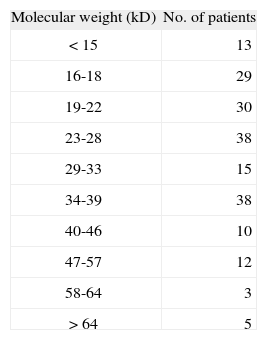

No binding bands were found with the serum of seven patients. They had no clinical difference with the other 38 patients, whose individual sera bound from one to ten IgE bands with the silverfish extract, as seen in Figure 1. Table II shows the number of patients who showed IgE binding bands according to the molecular weight (MW) of allergens: the most frequent ones were those in the range of 23-28 kD, and of 34-39 kD (compatible with the MW of Lep s 1, a tropomyosin). Few patients had bands with allergens larger than 64 kD.

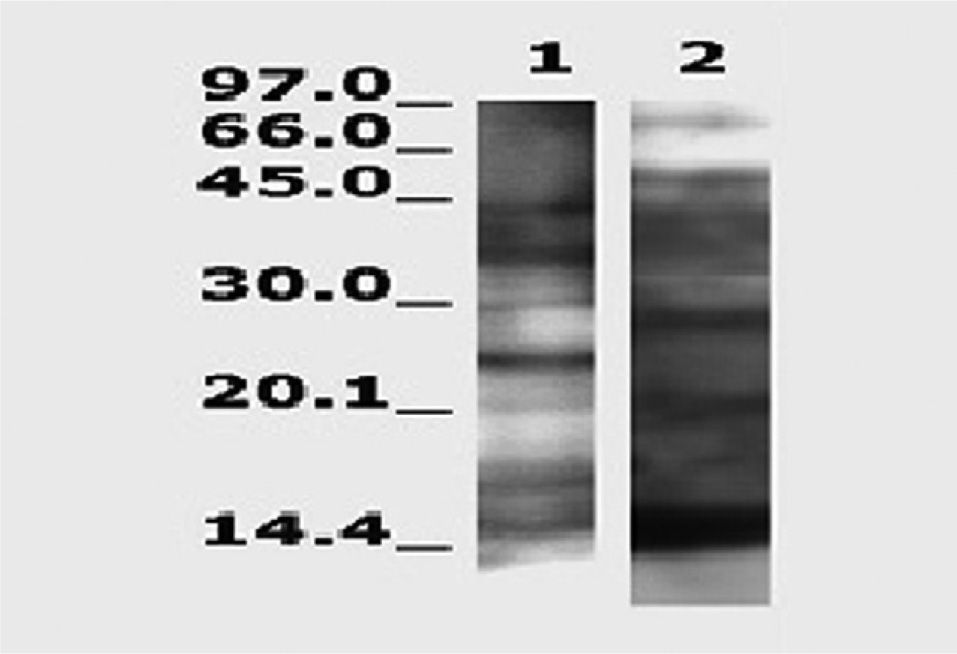

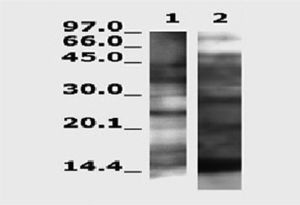

Figure 2 shows several distinct bands identified using the pool of selected sera with extracts of Lepisma and of D. pteronyssinus. There was a great difference between both extracts in the pattern of immunoblotting bands.

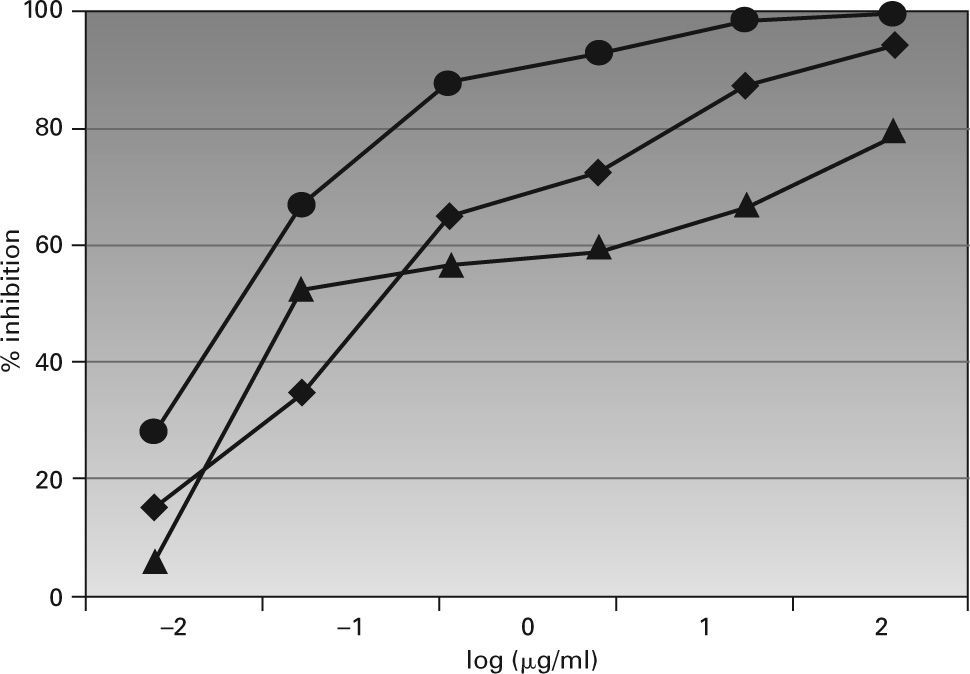

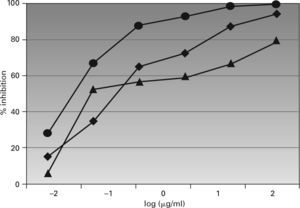

Figure 3 shows the results of the ELISA inhibition test, in which an inhibition > 90 % was found with the Lepisma extract at 2.5μg/mL; while a concentration of 250μg/mL was needed with the D. pteronyssinus extract to achieve a 94 % inhibition. The maximal value was 79 % for the cockroach extract, at the highest concentration. The logarithm of the concentration needed for a 50 % inhibition was –1.814 for Lepisma, –0.759 for D. pteronyssinus and –0.278 for cockroach extracts.

DISCUSSIONA domestic environment holds many potential inductors of sensitisation and allergic symptoms. Mites and cockroaches are well-known and extracts of these arthropods have been characterised and purified12–18, but many other hosts in houses must be considered. We chose to study the allergenicity of Lepisma because it is the most primitive living household insect, it finds an optimal habitat both in dwellings and work places, and due to its size, smaller than that of cockroaches, has an almost universal distribution.

Witteman et al developed two immunoassays to measure silverfish antigens and total tropomyosin in dust samples giving information about exposure to insects6. They found that house dust contained more tropomyosin than that coming from mites, so other arthropods were also contributing to the total amount of tropomyosin. Lepisma flees from daylight and humans, so it is sporadically seen, it does not appear in vacuum cleaned dust samples, and commercial monoclonal antibodies to measure its allergens are not available. Thus, exposure to silverfish is difficult to assess, and it is assumed due to its ubiquity as it is found in most dust samples6.

The information about allergenicity of Lepisma is very scarce. Barletta et al found that the classic aqueous extraction procedure was not completely adequate, because the insoluble allergenic material was normally discarded, and hence the allergenicity could be underestimated7. In previous studies, an important cross-reactivity among all the arthropods had been described, considering a panallergy that is sometimes extended to other invertebrates19–21.

The allergenic elements extracted from Lepisma saccharina were studied in the sera of 45 children with allergic respiratory symptoms. We found that there was a high frequency of an IgE binding protein with a MW in the region of approximately 34-39kDa, compatible with Lep s 1, a tropomyosin, which has been previously cloned22 and characterised as a cross-reactive inhalant/food allergen20,23. Sensitisation to this allergen might be due to primary sensitisation to L. saccharina or to cross-reactivity with tropomyosin of mites or cockroach, since 44 of our patients were sensitized to one or both of these allergens and there was also an ELISA inhibition with extracts of D. pteronyssinus and of cockroach. The concentration of the extract of D. pteronyssinus needed to achieve a > 90 % inhibition was 100 times that of the Lepisma extract; this could be due to the fact that tropomyosin is a minor mite component.

However, there were many other IgE binding bands and notable differences in the immunoblotting pattern of Lepisma compared to that of D. pteronyssinus. Some of the IgE binding bands could be assigned to cross-reactive carbohydrates determinants (CCD). Barletta found that periodate treatment of Lepisma extracts could completely abrogate, reduce or not affect at all IgE reactivity, so CCD could only partially account for IgE binding bands7. CCD are able to bind specific IgE in vitro, but not to simultaneously bind two molecules of IgE. Thus, they are not considered able to trigger symptoms or to give positive results in skin tests, which were found in our patients. Therefore, our results suggest that L. saccharina has specific allergens able to sensitise and induce an IgE response.

One limitation of our study is that we did not perform provocation tests but, nevertheless, the allergenic potential of Lepisma should be considered for sensitising and also as a triggering factor in patients sensitised to other cross-reactive allergens. Our study was not addressed at specifically studying the rate of sensitisation or identifying the patients at risk, but our findings should be taken into account in children or adults with allergic symptoms of presumed indoor origin. We suggest that sensitisation to Lepisma should be investigated in patients with suspect allergy symptoms in whom sensitisation to more common allergens has been ruled out, especially if the patient's environment contains numerous books and papers.

In summary, this study proves IgE sensitisation to Lepisma in children with respiratory allergy: it provides a biological basis, points out new clinical aspects of arthropod allergy, and suggests a possible role of Lepismatidae as causative agents of symptoms, which should be addressed and verified in further studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSWe thank Drs R. Molero-Baltanas, M. Gaju-Ricart and C. Bach de Roca from Dep. de Biología Animal (Zoología), Universidad de Cordoba and Dep. de Biología Animal, Vegetal y Ecología, Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona (Spain) for their helpful technical assistance.