Immunotherapy delivered a new therapeutic option to the oncologist: Ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4), Nivolumab and Pembrolizumab (anti-PD1), and Atezolizumab (anti-PD-L1) increase overall survival and show a better safety profile compared to chemotherapy in patients with metastatic melanoma, lung, renal cancer among others. But all that glitters is not gold and there is an increasing number of reports of adverse effects while using immune-checkpoint inhibitors. While chemotherapy could weaken the immune system, this novel immunotherapy could hyper-activate it, resulting in a unique and distinct spectrum of adverse events, called immune-related adverse events (IRAEs). IRAEs, ranging from mild to potentially life-threatening events, can involve many systems, and their management is radically different from that of cytotoxic drugs: immunosuppressive treatments, such as corticoids, infliximab or mycophenolate mofetil, usually result in complete reversibility, but failing to do so can lead to severe toxicity or even death. Patient selection is an indirect way to reduce adverse events minimizing the number of subjects exposed to this drugs: unfortunately PDL-1, the actual predictive biomarker, would not allow clinicians select or exclude patients for treatment with checkpoint inhibitors.

Immunotherapy is a new therapeutic option in oncology. The recent introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) has led to a paradigm shift in many cancers such as melanoma, lung or renal cancer among others. They are monoclonal antibodies against the checkpoint molecules CTLA 4, PD-1 and PD-L1 antigens.

CTLA-4, a homolog of CD28, bound with higher affinity to B7-1 and B7-2 and inhibited CD4 T-cell activation; so anti-CTLA-4 (Ipilimumab) promoted CD4 T-cell activation against the tumor.

PD-1 expression on T-cells, which can interact with PD-L1 expressed on cancer cells, inhibiting T-cell activation and perhaps inducing a state of anergy in immune cells present in the tumor. Blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway with Nivolumab/Pembrolizumab (anti-PD1) or Atezolizumab (anti-DL1) can revert this condition, promoting cancer cell elimination by activated T-cells.

Other specific immunotherapies such as vaccines, T-cell engager or oncolytic virus are under investigation.

Checkpoint inhibitors have shown a significant improvement in overall survival in metastatic diseases; even after discontinuation of treatment, a high percentage of patients maintained a prolonged tumor response. Nevertheless, the immune response leads to different adverse effects from those produced by traditional chemotherapy or targeted therapies; chemotherapy produces adverse events related to a weakened immune system, while immuno-checkpoint generate an overstimulated immune system leading to “auto-immune like adverse events” (IRAEs). They may appear at the beginning, during or after the end of treatment.

The most frequent manifestations are dermatological, digestive and endocrine, but renal-, pulmonary- and nervous system-related disorders may also occur, among others. The onset of the toxicity is in the first 16 weeks in 85% of the cases.1

They range from mild and reversible to life-threatening and early recognition seems to be the key to avoid adverse fatal events. Approximately 58–85% of toxicity is reversible after steroid treatment if started promptly.2

Reversible IRAEs included fatigue, pruritus, rash, myalgia, arthralgia, loss or change of appetite and hypo-hyperthyroidism. Other irreversible adverse events consist of diabetes mellitus, uveitis, arthritis and, in some cases, of hypothyroidism.3 Severe IRAEs that can be potentially life-threatening are hepatitis, colitis, hypophysitis, pneumonitis, myocarditis, Guillain–Barré, myasthenia gravis and encephalitis. For their proper management, early detection is very important and thus starts the appropriate treatment as soon as possible; so, deep knowledge of IRAEs is a priority for oncologists of the new era.

The efficacy of immunotherapyTreatment with immunotherapy seems to be effective for different tumor histologies and independent of driver mutations. The survival benefit and response rate are different depending on the drug used, but adverse events are very similar.

IpilimumabIpilimumab is a fully human monoclonal IgG1 anti-CTLA-4 antibody. It was the first to be approved by the FDA and EMA. In 2011, as second-line for metastatic melanoma, and 2 years later, in 2013, as first-line for the same situation after showing benefit in survival rate.4

In 2015, Schandenford5 published results of an analysis of pooled OS data from several clinical trials phase II and III. Imipilimumab improves OS until 11.4 months (95% CI, 10.7–12.1 months) with a 3-year survival rate of 22% (95% CI, 20–24%). In addition, as of the third year of treatment, a plateau appears and extends up to 10 years in some patients.

The most recent research evaluates the role of ipilimumab in the adjuvant setting for melanoma stage III. In a phase III study, it was compared to placebo after adequate surgery. Patients received ipilimumab or placebo and the median recurrence-free survival was 26.1 months vs. 17.1 months, respectively, with a 3-year recurrence-free survival of 46.5% vs. 34.8%.6 Data of OS is not available yet.

NivolumabNivolumab is a human monoclonal IgG4 anti-PD-1 antibody. In 2014, it obtained its first approval for unresectable or metastatic melanoma after ipilimumab or a BRAF inhibitor. Previously, the results of CheckMate-037 had demonstrated that ORR was 31.7% (95% CI, 23.5–40.8) for nivolumab vs. 10.6% (95% CI, 3.5–23.1) in the chemotherapy group, after ipilimumab.7

In 2015, approval of nivolumab was extended to other indications such as squamous and non-squamous NSCLCs after progression on platinum chemotherapy, metastatic RCC after progression on antiangiogenic therapy and, later CheckMate-066 showed an HR 0.42 in favor of nivolumab against dacarbazine and a 1-year OS rate of 72.9% vs 42.1%, respectively, with ORR 40% with nivolumab vs 13.9% with dacarbazine, Nivolumab was also approved as first-line therapy of metastatic melanoma.

Recently, in February 2017, nivolumab was approved by the Food and Drug Administration for bladder cancer platinum-pretreated patients.

PembrolizumabPembrolizumab is a fully humanized monoclonal IgG4 anti-PD-1 antibody. In 2014, Pembrolizumab was approved by the FDA for unresectable or metastatic melanoma after Ipilimumab, but in 2015 the phase III trial Keynote-006 evidenced a significant improvement in OS in favor of Pembrolizumab.8 So Pembrolizumab was approved for first-line therapy of metastatic melanoma. The same year, the approval for PD-L1+advanced NSCLC was obtained, previously treated based on the results of the KEYNOTE-010 study.

March 2017, phase III trial KEYNOTE-045 demonstrated a significant benefit in survival in patients treated with pembrolizumab compared with the standard second-line chemotherapy.

AtezolizumabAtezolizumab is a fully humanized monoclonal IgG1 anti-PD-L1. To date, it has only been approved by the FDA as the second line for advanced NSCLC and locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Approval for NSCLCs was based on the results of OAK and POPLAR trial, where a clear improvement in overall survival was demonstrated against chemotherapy. It was approved in 2016, for urothelial cancer pretreated with platinum based on IMvigor 210 phase II trial.

Benefit of combination immunotherapyThe most recent studies investigate the combined use of immunotherapy with other immunotherapy drugs or chemotherapy, target therapy and radiotherapy. The hypothesis is that the combined treatment has a synergistic or additive effect. The main problem is the increase in serious adverse effects.

The phase III CheckMate 067 compared ipilimumab alone vs. nivolumab alone vs. nivolumab and ipilimumab in combination for untreated patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma.3 The results showed a significant improvement in favor of combination: PFS 11.5 months with combination vs. 6.9 months with nivolumab vs. 2.9 months with ipilimumab, HR 0.42 (99.5% CI 0.31–0.57) and ORR was 57.6% vs. 43.7% and 19%, respectively.

On the other hand, a phase II KEYNOTE-021 evaluated the effect of adding pembrolizumab to carboplatin and pemetrexed for metastatic non-squamous lung cancer. The combination obtained an ORR of 55% vs. 29% for chemotherapy alone.8

More studies are necessary to understand the efficacy and safety of different possible combinations of treatment.

Persistent responsesIt seems surprising that patients who discontinued treatment with immunotherapy for other reasons than tumors progression, primarily toxicity, continued to respond (complete or partial response) in up to 70% of cases.3 Currently, the question is how long should we treat patients with immunotherapy. More studies are necessary to answer this question.

Immune toxicity spectrum of checkpoint blockade agentsDermatologicalThe dermatological manifestations are the most common and those that appear earliest, approximately 2–3 weeks after the beginning of the treatment. It is common to see them after the first dose.1 The most frequent are pruritus, maculopapular rash, erythema, alopecia, hypertrichosis, lichenoid keratosis and vitiligo. Other rarer and potentially fatal are the Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrosis. They are more common with CTLA 4 inhibitors, however oral mucositis and vitiligo are more prevalent with anti-PD1/anti-PD-L1 therapy,9 approximately 47–68% patients on anti-CTLA-4 therapy and 30–40% with anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 therapy. For diagnosis, the tools we can use depend on the severity: mucocutaneous examination, serum tryptase and IgE levels and skin biopsy depending on the grade of severity.

GastrointestinalThis type of events usually appears 5–10 weeks after the second dose. Among the digestive manifestations are diarrhea, colitis, nausea, vomiting, gastritis, pancreatitis, celiac disease.1 The anti-CTLA4, especially Ipilimumab, is the one that has been mostly related to diarrhea and colitis (30–40%).4 However, it has been seen that patients subsequently treated with anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 antibodies do not develop diarrhea or colitis.10

To identify this is prior to doing the differential diagnosis with stool microscopic examination for ova, parasites, stool culture and stool antigen for c. Difficile, evaluate progression of primary disease and endoscopy.

LiverDisorders of the liver appear 12–16 weeks after starting treatment with Ipilimumab. It is often seen after administration of the third dose.1 Hepatitis should always be suspected of an unexplained elevation of transaminases. It can be asymptomatic or accompanied by fatigue and fever. It appears in 10% of patients treated with anti-CTLA 4 and about 20% of patients treated with the combination of anti-CTLA 4 and anti PD1/PD-L1.1 To start the diagnosis, the first thing to do is to rule out secondary causes such as infection with a hepatotropic virus with serologies, liver metastases with CT and finally a liver biopsy.

EndocrineUsually, these effects appear 9 weeks after initiation of treatment with Ipilimumab.1 The alterations that may appear are hyper/hypothyroidism, hypophysitis, adrenal insufficiency and diabetes. Hypothyroidism is more prevalent with anti-CTLA 4, while hyperthyroidism and hypophysitis are more prevalent with anti-PD-1 and anti-PDL1 antibodies.1

It is difficult to diagnose these entities due to their non-specific symptoms: fatigue, anorexia, nausea and headache. The diagnosis is mainly made with hormonal determinations: TSH, ACTH, LH, FSH, prolactin, GH and testosterone.

LungThe manifestations that may appear are pneumonitis, pleuritis and sarcoid-like granulomatosis.

Pneumonitis is the most frequent and appears in 1% of patients treated with anti-CTLA 4 and approximately 5–7% of grade 3 or higher in patients with NSCLC treated with Nivolumab and Pembrolizumab.11

It should be ruled out in all patients who begin with progressive shortness of breath, dry cough and fever. The suggested tests are CT and bronchoscopy to rule out an infectious cause.

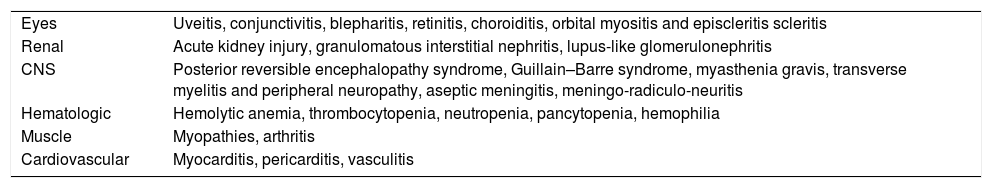

Other manifestations are listed below (Table 1).

Other manifestations.

| Eyes | Uveitis, conjunctivitis, blepharitis, retinitis, choroiditis, orbital myositis and episcleritis scleritis |

| Renal | Acute kidney injury, granulomatous interstitial nephritis, lupus-like glomerulonephritis |

| CNS | Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, Guillain–Barre syndrome, myasthenia gravis, transverse myelitis and peripheral neuropathy, aseptic meningitis, meningo-radiculo-neuritis |

| Hematologic | Hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, pancytopenia, hemophilia |

| Muscle | Myopathies, arthritis |

| Cardiovascular | Myocarditis, pericarditis, vasculitis |

In recent years, immunotherapy has demonstrated its usefulness in many types of tumors and the number of patients receiving this kind of treatment is increasing, although these new immunotherapies also generate dysimmune toxicities by unbalancing the immune system, favoring the development of autoimmune manifestations.12

In this setting, many guidelines have been developed and they all agree with the use of corticosteroids and immune-modulating agents. But the management of IRAEs is more complex, the Gustave Rousy Cancer Center published a guideline that comprises five pillars: these are prevent, anticipate, detect, treat and monitor the IRAEs.9

In preventing, it is important to know the immune toxicity spectrum as we describe previously and identify dysimmunity risk factors as personal and family history of autoimmune disease or the presence of opportunistic infections (tuberculosis infection, pneumocystis pneumonia, chronic hepatitis, etc.) because the administration of immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) could be responsible for inflammatory reactions against such pathogens by refreshing the anti-pathogen immune response.9

To anticipate the Gustave Rousy, an immunotherapy baseline checklist has been developed 9 that could be useful in identifying the occurrence of new abnormalities or toxicity. When a new abnormality is detected, it is important to rule out it being secondary to a disease progression or a fortuitous event before defined as a treatment-related dysimmune toxicity. For example, in a meta-analysis about safety and efficacy of Nivolumab,13 the risk of IRAEs grade ≥3 is only 0.12 and the most common grade ≥3 were hypophosphatemia (2.3%) and lymphopenia.

Currently, management guidelines are based on empirically directed immune-modulating agents (corticotherapy and immunosuppressive drugs) and on the knowledge of autoimmune diseases.14 Before the initiation of corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive drugs, it is necessary to rule out any associated infection.

Corticosteroids should be employed at initial doses used to treat autoimmune diseases (1mg/kg/day or more), the duration is generally of 2–4 weeks and 58–85% of toxicity is reversible with steroid treatment2; afterwards, corticosteroids must be reduced gradually over a period of at least 1 month to avoid the IRAE from recurring.12

When the IRAEs are steroid-refractory, immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive agents such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha antagonists, azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) may be effective.15 While the anti-TNF-alpha has an immediate therapeutic effect,16 the other immunosuppressive drugs such as azathioprine and MMF only become effective after several weeks.

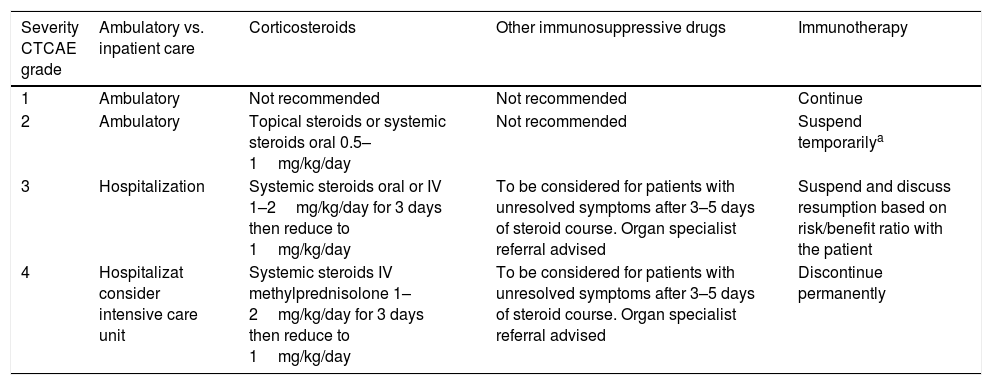

Another key point relates to if the management should be ambulatory or inpatient care, guidelines suggest that grade ≥3 IRAEs should be treated inpatient (Table 2).

Management of IRAEs.12

| Severity CTCAE grade | Ambulatory vs. inpatient care | Corticosteroids | Other immunosuppressive drugs | Immunotherapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ambulatory | Not recommended | Not recommended | Continue |

| 2 | Ambulatory | Topical steroids or systemic steroids oral 0.5–1mg/kg/day | Not recommended | Suspend temporarilya |

| 3 | Hospitalization | Systemic steroids oral or IV 1–2mg/kg/day for 3 days then reduce to 1mg/kg/day | To be considered for patients with unresolved symptoms after 3–5 days of steroid course. Organ specialist referral advised | Suspend and discuss resumption based on risk/benefit ratio with the patient |

| 4 | Hospitalizat consider intensive care unit | Systemic steroids IV methylprednisolone 1–2mg/kg/day for 3 days then reduce to 1mg/kg/day | To be considered for patients with unresolved symptoms after 3–5 days of steroid course. Organ specialist referral advised | Discontinue permanently |

Finally, monitor evolution, the time needed for IRAEs resolution can vary highly across the various types of toxicities. For example, the median time to resolution of IRAEs of any grade secondary to nivolumab ranged from 3.3 weeks for hepatic AEs to 28.6 weeks for the skin,2 in addition to being aware of the risk of relapse or recurrence of IRAEs or for immunosuppression complications.9

Relation between IRAEs and response ratesThe presence of adverse effects related to treatment with some anti-tumor drugs such as anti-EGFR has been associated with a higher rate of response. In the case of IRAEs to immunotherapy, their relationship between their presence and the response rate is not completely clear. In a retrospective review of patients with ipilimumab-treated melanoma,17 no difference in OS or TTF was detected when patients were stratified by the presence or absence of IRAEs of any grade.

In another retrospective analysis of patients with melanoma treated with nivolumab, in a multivariable analysis adjusting for differences in the number of nivolumab doses received, baseline LDH and tumor PD-L1 expression ORR was significantly better in patients who experienced IRAEs of any grade compared with those who did not, with greater benefit in patients who reported three or more IRAEs.2

With current evidence, it cannot be concluded if the presence of IRAEs is related to the rate of response, PFS or OS.

Impact of use of immune-modulating agents (IMs)The use of immune-modulating agents (corticosteroids and immunosuppressive drugs such as anti-TNF-alpha or mycophenolate), due to their immunosuppressive effect, might be related to a decreased effectiveness of immunotherapy; however, several studies reported that there is no significant difference in the ORRs between patients who received this kind of treatment versus those who did not receive IMs.

For example, in a retrospective analysis that includes two phase III trials with patients who received nivolumab 3mg/kg/2 weeks for melanoma, the ORR was 29.8 in the group of patients that received IMs and 31.8 in the group of patients that did not receive IMs.2

In another retrospective review of patients with melanoma treated with Ipilimumab, there was no difference in OS or TTF when patients were stratified by the administration of systemic corticosteroids to treat an IRAEs.17

ConclusionImmunotherapy is a promising approach for the treatment of cancer, probably changing the paradigm of this illness. The independence from tumor histologies and/or driver mutation could reduce the necessity for repeated biopsy, improving the quality of life and lowering the rate of adverse effects.

Sustained response even when patients discontinue treatment will oblige the oncologist to create the term “treatment-free survival” to indicate patients without cancer progression and without active treatment.

However, all that glitters is not gold and immunotherapy-treated patients could experiment life-threatening adverse effects especially when physicians fail to follow the five pillars of immunotherapy published by the Gustave Rousy Cancer Center; prevent possible adverse effect and strict monitoring of our patients is essential to avoid the potentially harmful effect of immune-checkpoint inhibitors.

Another big issue is patient selection, nowadays PDL-1 is far from the “perfect” predictive biomarker. As stated previously, PDL-1/PD-1 inhibitors release the brake to allow T-cells to fight cancer by inhibiting immune system checkpoints. This strategy allows us to fight cancer when the battlefield is downhill or when the tumor is “immunogenic” (hot) while it is clear. It is useless when the cancer is low immunogenic (cold tumor). Immune-checkpoint inhibitors need an activated immune system to work: the next challenge is to find a clinical marker capable of differentiating a “hot” or a “cold” immune system, allowing the physician to decide which patients could benefit from these molecules.

Oncologists are at the beginning of a new age of cancer treatment: we are but a few steps away from changing the paradigm of cancer treatments allowing patients to have a treatment with pleiotropic, long-lasting and less toxic effects using our immune system to fight The Emperor of All Maladies.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.