Background. The relative incidence of bleeding and thrombotic events and the use of blood products in hospitalized cirrhosis patients have not been widely reported. We aimed to estimate the magnitude of bleeding events and venous thrombosis in consecutive hospitalized cirrhotic patients over a finite time period and to examine the amount and indications for blood product use in cirrhosis patients admitted to a tertiary care center.

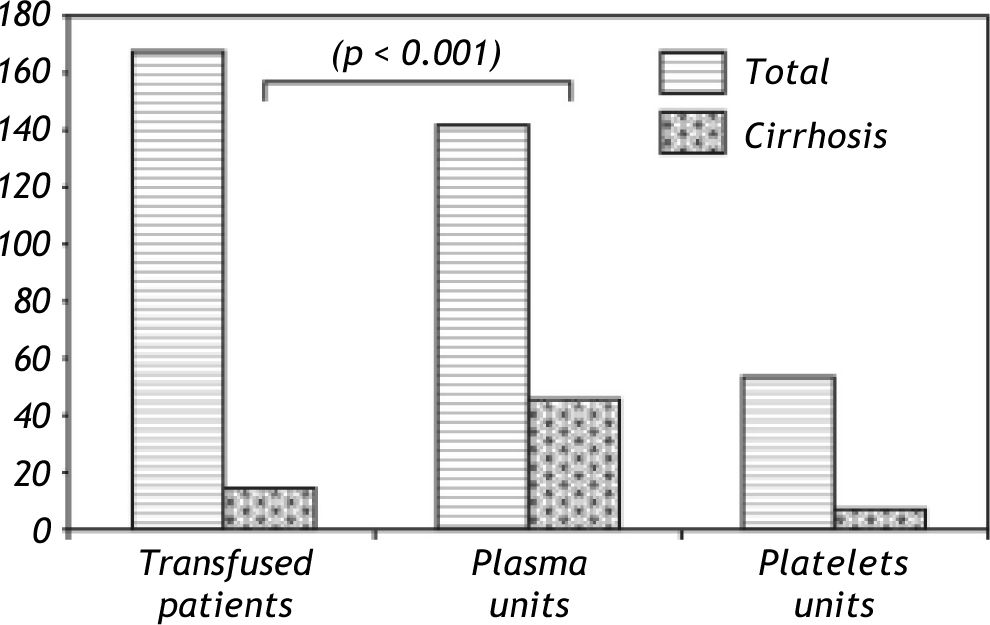

Results. Among patients admitted with decompensated liver disease, 34 (40%) suffered bleeding events (about one-half non-variceal) and 6 patients (7%) suffered deep venous thrombosis. In the blood product survey, 168 patients were transfused with plasma or platelets during the survey intervals. Liver disease patients accounted for 7.7% of the total but disproportionately consumed 32.4% (46 of 142) of the units of plasma mostly administered as prophylaxis. In contrast, cirrhosis patients received only 7 of the 53 units of platelets transfused (13.2%) during the survey intervals.

Conclusions. Coagulation issues constitute a common problem in patients with liver disease. Recent advances in laboratory testing have shown that stable cirrhosis patients are relatively hypercoagulable. The result of this prospective survey among decompensated (unstable) cirrhosis patients shows that, while DVT is not uncommon, bleeding (non-variceal in one half) remains the dominant clinical problem. This situation likely sustains the common practice of plasma infusion in these patients although its use is of unproven and questionable benefit. Better clinical tools are needed to refine clinical practice in this setting.

Chronic liver disease exerts a significant burden of care on the medical field.1 Patients are often hos-pitalized for various complications related to their liver disease, and matters of coagulation or hemostasis often affect their course. Cirrhosis is characterized by complex hemostatic defects including thrombocytopenia, increased platelet adherence due to von Willebrand factor, reduced liver synthesized pro-and anti-coagulation factors, increased endothelial derived pro-coagulant factors such as factor VIII and hyperfibrinolysis.2-7 These changes lead to increased bleeding risk and to the more recently recognized and somewhat paradoxical increased thrombotic risk.8-10 However, the magnitude of these opposing conditions among decompensated and hospitalized cirrhosis patients has not been well characterized especially in terms of the incidence and the effect of these problems on blood product use. As newer management strategies emerge to treat hemostatic problems in cirrhosis, it is important to better understand the relative impact of these conditions.

In this study, we aimed to estimate the incidence of bleeding and/or documented thrombotic episodes in a hospitalized liver disease population over a defined period of time. In a separate 'point in time' a survey, we assessed the magnitude of plasma and platelets transfusions administered to patients with advanced liver disease patients in a tertiary care hospital. We did not seek to determine predictors of bleeding in this work, but rather we aimed more simply to determine the magnitude of these opposing problems and the current use of blood products.

Material and MethodsWe completed a prospective Quality Indicator Survey of the inpatient hepatology service from December 2009 to January 2010. Over a continuous 6-week period we monitored the inpatient Hepatology Service at the University of Virginia to identify episodes of bleeding or thrombotic problems among patients admitted with decompensated cirrhosis. Episodes of bleeding were defined as clinically apparent blood loss requiring intervention and included variceal bleeding or other gastrointestinal bleeding, mucosal bleeding, puncture wound bleeding, epistaxis, large, spontaneous internal hematomas or extensive external hematomas involving the majority of a limb or flank surface area and bleeding post-procedures such as dental extractions. Thrombotic events included peripheral and visceral deep vein thrombosis confirmed by radiographic imaging.

In a separate study performed over a randomly chosen 15-day period, medical center blood product use was surveyed on three non-consecutive days. The days were spaced (days 1, 7 and 15) to avoid patient overlap during longer hospitalizations. On each of these three days, we obtained blood bank records detailing fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and plate-let transfusions. From these records, patients with liver disease were identified. We then determined the pre-transfusion indication, the amount of blood products given, and the subsequent clinical course. The liver disease patients, course was also assessed for two days post-transfusion to determine side-effects and outcomes.

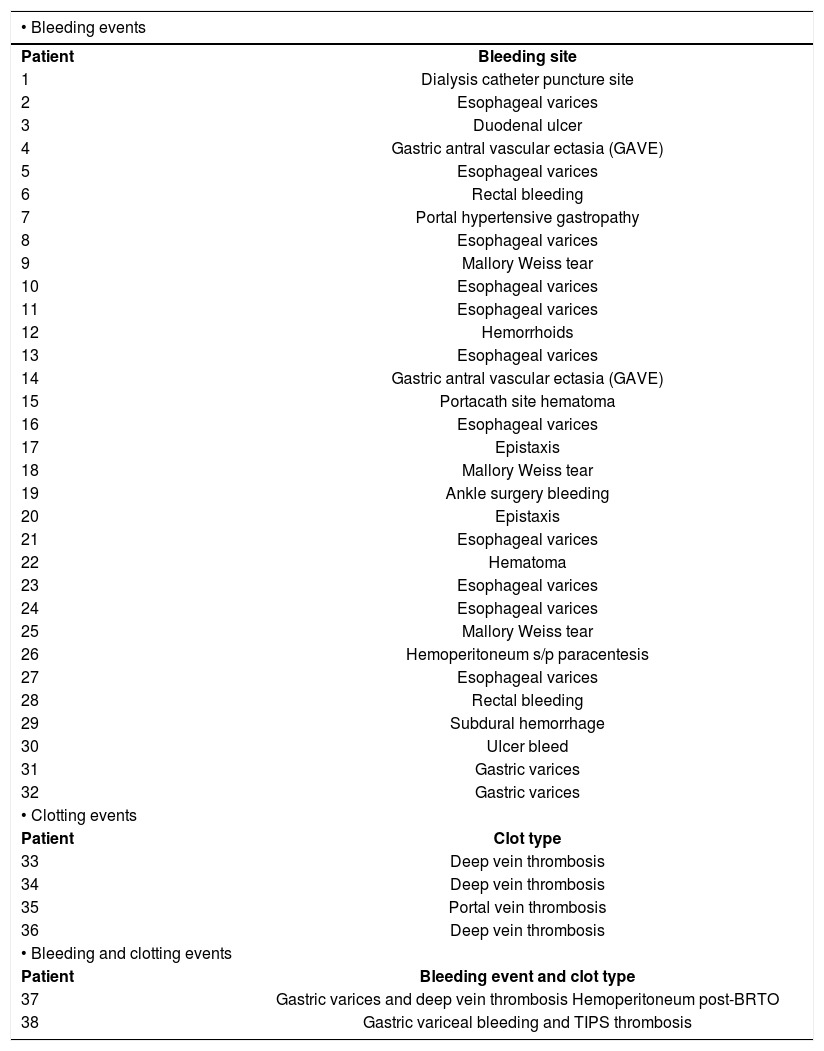

ResultsBleeding and thrombotic events in decompensated cirrhosisOver the 6-week period, there were 85 admissions of decompensated cirrhosis to the inpatient service. A total of 34 of 85 patients (40%) suffered bleeding events during this time (Table 1). About one half were non-variceal. GI bleeding was the most common cause occurring in 23 patients with 14 episodes of variceal bleeding and 10 episodes of non-variceal GI bleeding. Non-variceal GI bleeding resulted from various causes including 3 portal hypertensive gastropathy bleeds, 3 Mallory Weiss tears, 2 peptic ulcer bleeds, 2 episodes of epistaxis, and 1 hemorrhoidal bleed (Table 1). As per our previously defined criteria for bleeding, all 34 patients with an event received some type of intervention, and many received multiple blood products and pro-coagulants: 91% of patients were transfused with packed red blood cells, 65% were transfused with platelets, and 44% were transfused with fresh frozen plasma. During the same time period, six patients (7%) suffered thrombotic events: 4 had peripheral acute deep vein thrombosis, 1 had acute portal vein thrombosis, and 1 suffered a TIPS thrombosis 7 months after the initial placement of the TIPS. Notably, none of these patients were on subcutaneous heparin prophylaxis. Two patients suffered both a bleeding and a clotting episode during the same hospital admission. One patient was treated acutely for a gastric variceal bleed with TIPS, and subsequently suffered a thrombosis of the shunt. Another patient presented with a gastric variceal bleed and developed a lower extremity deep vein thrombosis.

Bleeding and clotting events over 6 weeks (85 admissions).

| • Bleeding events | |

|---|---|

| Patient | Bleeding site |

| 1 | Dialysis catheter puncture site |

| 2 | Esophageal varices |

| 3 | Duodenal ulcer |

| 4 | Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) |

| 5 | Esophageal varices |

| 6 | Rectal bleeding |

| 7 | Portal hypertensive gastropathy |

| 8 | Esophageal varices |

| 9 | Mallory Weiss tear |

| 10 | Esophageal varices |

| 11 | Esophageal varices |

| 12 | Hemorrhoids |

| 13 | Esophageal varices |

| 14 | Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) |

| 15 | Portacath site hematoma |

| 16 | Esophageal varices |

| 17 | Epistaxis |

| 18 | Mallory Weiss tear |

| 19 | Ankle surgery bleeding |

| 20 | Epistaxis |

| 21 | Esophageal varices |

| 22 | Hematoma |

| 23 | Esophageal varices |

| 24 | Esophageal varices |

| 25 | Mallory Weiss tear |

| 26 | Hemoperitoneum s/p paracentesis |

| 27 | Esophageal varices |

| 28 | Rectal bleeding |

| 29 | Subdural hemorrhage |

| 30 | Ulcer bleed |

| 31 | Gastric varices |

| 32 | Gastric varices |

| • Clotting events | |

| Patient | Clot type |

| 33 | Deep vein thrombosis |

| 34 | Deep vein thrombosis |

| 35 | Portal vein thrombosis |

| 36 | Deep vein thrombosis |

| • Bleeding and clotting events | |

| Patient | Bleeding event and clot type |

| 37 | Gastric varices and deep vein thrombosis Hemoperitoneum post-BRTO |

| 38 | Gastric variceal bleeding and TIPS thrombosis |

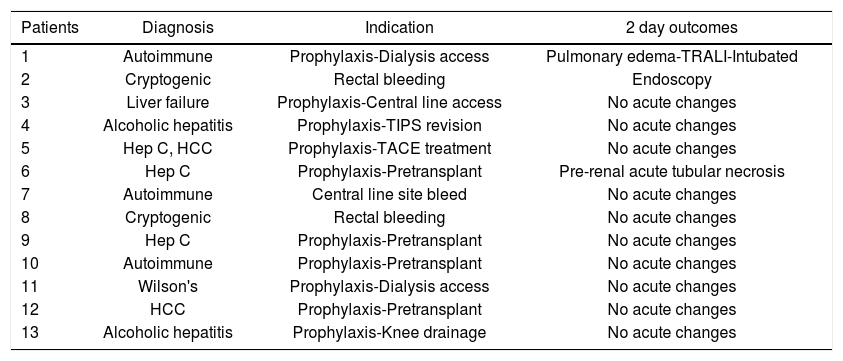

A total of 168 patients were transfused with plasma and/or platelets during the three separate days that blood bank records were surveyed. Although there were a total of only 13 cirrhotic patients (7.7%) in the entire sample of transfused patients during these three intervals, liver disease patients consumed 46 of the 142 units of FFP administered (32.4%), and 7 of the 53 units of platelets transfused (13.2%) (Figure 1). Of the cirrhotic patients transfused, 3 of the patients had documented bleeding as the primary indication for transfusion, while the remaining 10 were given products for prophylaxis, 9 for pre-procedural prophylaxis (Table 2). No acute febrile transfusions reactions were documented although one patient with autoimmune liver disease who received prophylactic plasma for dialysis catheter insertion had a chest X-ray consistent with severe pulmonary edema and required mechanical ventilation within 48 hours post-transfusion. Clinically, this suggested TRALI (transfusion-related acute lung injury), but definitive diagnostic studies were not performed.

Transfusion of plasma and platelets in total and in cirrhosis patients. While cirrhosis patients constituted only 7.7% of all patients receiving these blood products in the study intervals, they disproportionately consumed 32% of plasma units (p < 0.001 Fisher exact test). Platelet use in cirrhosis was relatively low (13% of total) which is somewhat paradoxical in light of recent laboratory advances in cirrhotic hemostasis as discussed in the text.

Diagnosis, indication, and outcomes for transfused patients.

| Patients | Diagnosis | Indication | 2 day outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Autoimmune | Prophylaxis-Dialysis access | Pulmonary edema-TRALI-Intubated |

| 2 | Cryptogenic | Rectal bleeding | Endoscopy |

| 3 | Liver failure | Prophylaxis-Central line access | No acute changes |

| 4 | Alcoholic hepatitis | Prophylaxis-TIPS revision | No acute changes |

| 5 | Hep C, HCC | Prophylaxis-TACE treatment | No acute changes |

| 6 | Hep C | Prophylaxis-Pretransplant | Pre-renal acute tubular necrosis |

| 7 | Autoimmune | Central line site bleed | No acute changes |

| 8 | Cryptogenic | Rectal bleeding | No acute changes |

| 9 | Hep C | Prophylaxis-Pretransplant | No acute changes |

| 10 | Autoimmune | Prophylaxis-Pretransplant | No acute changes |

| 11 | Wilson's | Prophylaxis-Dialysis access | No acute changes |

| 12 | HCC | Prophylaxis-Pretransplant | No acute changes |

| 13 | Alcoholic hepatitis | Prophylaxis-Knee drainage | No acute changes |

HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma. TRALI: transfusion related lung injury.

Among 85 consecutive decompensated cirrhosis patients admitted to an inpatient Hepatology Service over a 6 week period, 34 patients (40%) suffered a bleeding episode and 6 patients (7%) suffered deep venous thrombotic disease. Collectively, 50% of these admissions had some type of complication related to bleeding or clotting during their hospital stay. In a separate survey, this study confirmed a common clinical suspicion that liver disease patients used a significant and disproportionate amount of procoagulant blood products dispensed from a tertiary care center blood bank. Although liver disease patients constituted 7.7% of all inpatients and outpatients receiving transfusions during the times surveyed, these patients utilized 32% of administered plasma and 13% of platelets. Our work provides a fresh perspective on the magnitude of hemostatic problems in cirrhosis in light of recent laboratory advances.

The fields of hematology and hepatology interface extensively because of the central role of the liver in the synthesis of pro-and anti-coagulation factors and hepatic clearance of by-products of hemostasis and coagulation. As a result, indices of coagulation are an essential part of prognostic scoring systems for advanced liver disease such as the MELD score. Although for many years the coagulopathy of liver disease was felt to result in 'auto-anticoagulation', recent studies have refuted this concept.11 It is now apparent that patients with cirrhosis may be relatively hypercoagulable regardless of conventional indices such as the INR. This situation results from the deficit of liver-derived protein C and increased endothelial-derived factor VIII along with intact endothelial thrombomodulin function. Coagulation is further augmented in cirrhosis through increased von Willebrand factor which enhances platelet adhesion.7 Other conditions such as volume overload, renal failure, infection, endothelial dysfunction, or hyperfibrinolysis are often superimposed and result in severe hemostatic instability. In this setting, it is thus not surprising to encounter both bleeding and thrombotic issues in this patient population. In fact, two of the patients included in the study suffered from both a bleeding and clotting event during the same hospital admission. This reinforces the complexity of the hemostatic system in cirrhotic patients.

Measuring the relative risk of bleeding or thrombotic problems in a particular patient is challenging with conventional coagulation indices such as the INR as this test cannot account for the changes in the pro-coagulant pathways discussed above. Reproducibility of this test as conventionally performed for warfarin therapy has also proven to be dependent on commercially prepared thromboplastins (used in the prothrombin time reaction) in cirrhosis.12,13 In spite of these marked limitations, published guidelines have continued to advocate old 'cut-offs' for the INR as relatively more or less safe in the setting of invasive procedures.2 This has led to the persistent clinical practice of pre-procedure plasma administration although the efficacy of this strategy is highly questionable and the practice has largely been abandoned as a routine in liver transplant surgery.14 Nonetheless, this practice accounted for the majority of plasma utilization in our point in time assessment of blood product use in cirrhosis patients.

Our report has several inherent limitations. This was an observational study and although limited outcomes data were available in some aspects of the study, we lacked details on laboratory values, prior bleeding episodes or co-existing conditions such as infection or renal failure. We did not seek to determine predictors of bleeding or clotting in this study. Others have shown that the conventional laboratory based indices (INR for example) are of questionable value in this setting.15 On the other hand, our aim was to provide a snapshot view of the magnitude of the problems of bleeding and deep vein thrombosis and the impact of hemostatic uncertainties on blood bank utilization in cirrhosis. To this end, our results show that indeed both problems are significant among cirrhosis patients in a tertiary care facility and the impact on blood product utilization remains substantial in spite of advances in the laboratory based understanding of coagulation in liver disease. These results will be useful in the development of further studies aimed at refining clinical strategies for managing hemostasis in cirrhosis.

Abbreviations- •

FFP: fresh frozen plasma.

- •

TIPS: transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

- •

INR: international normalized ratio.

Funding was provided by the University of Virginia, no conflicts of interest exist for Shah, Northup, or Caldwell.

IrbThis study was approved by the University of Virginia Institutional Review Board.