Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a rare disease with a complex and not fully understood pathogenesis. Prognostic factors that might influence treatment response, relapse rates, and transplant-free survival are not well established. This study investigates clinical and biochemical markers associated with response to immunosuppression in patients with AIH.

Materials and MethodsThis retrospective cohort study included 102 patients with AIH treated with immunosuppressants and followed at the Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil, from 1990 to 2018. Pretreatment data such as clinical profiles, laboratory, and histological exams were analyzed regarding biochemical response at one year, histological remission, relapse, and death/transplantation rates.

ResultsCirrhosis was present in 59 % of cases at diagnosis. One-year biochemical remission was observed in 55.7 % of the patients and was found to be a protective factor for liver transplant. Overall survival was 89 %. Patients with ascites at disease onset showed a higher aspartate aminotransferase (AST)/ alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ratio and elevated Model of end-stage liver disease (MELD) score. The presence of ascites was significantly associated with a 20-fold increase in mortality rate.

ConclusionsAIH has a severe clinical phenotype in Brazilians, with high rates of cirrhosis and low remission rates. Early diagnosis and treatment are essential for achieving remission and reducing complications. The presence of ascites is significantly associated with mortality, emphasizing the importance of monitoring and prompt intervention. This study also stresses the need for further research on AIH in Latin America.

Autoimmune hepatitis was first described in Sweden in 1950, and it is a rare and complex disease. Although its pathogenesis remains incompletely understood, it is acknowledged that hepatocyte injury ensues through an inflammatory cascade triggered by a likely alteration in the immune system involving antigenic tolerance in individuals with genetic predisposition [1,2]. The presentation spectrum is broad, ranging from mild hepatitis to acute liver failure, though the latter is infrequent. Approximately 30 % of patients exhibit insidious and asymptomatic disease, while nearly 70 % may present with cirrhosis [3]. Treatment primarily involves immunosuppression, resulting in a favorable biochemical response for most patients. On the other hand, complete histological remission and corticosteroid-free remission are less common [4].

Studies on AIH in Latin America have generally been small, with limited sample sizes, and have often focused on specific populations or subgroups. This scarcity of data on AIH in Latin America is a concern, as it can make it more difficult for healthcare providers to accurately diagnose and treat patients with this condition [5]. Although there is limited epidemiological data available in Brazil, reference centers report that autoimmune etiology is responsible for 5–19 % of liver diseases. Moreover, the natural history of AIH in Brazil is described as more severe, often presenting with cirrhosis at disease onset and associated with lower immunosuppression response rates compared to international literature [3]. In this context, the main objective of this study is to investigate clinical, laboratory, and histological markers associated with response to treatment in AIH patients. The secondary aim is to describe the epidemiological profile of AIH in this population, including the severity of presentation, relapses, liver transplant rates, and mortality.

2Materials and methodsThis is an observational, retrospective cohort study. The study population comprised adult patients older than 18 who met the probable or definite criteria for AIH diagnosis according to the simplified score of the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) [6]. One hundred thirty-three AIH patients were enrolled from 1990 to 2018 at the Liver Outpatient Clinic from the Hospital das Clínicas of the Federal University of Minas Gerais. Overlap autoimmune syndromes, such as primary sclerosing cholangitis and, primary biliary cholangitis, and drug-induced liver injury, were exclusion factors, leading to a final sample of 102 patients. The data collected included gender, age at diagnosis, AIH type, concomitant liver disease, and alcohol abuse. At diagnosis, we analyzed the presence of cirrhosis (diagnosed by ultrasound or liver biopsy) and liver-related complications, such as ascites (clinically detected or identified by ultrasound examination) and the presence of clinically significant portal hypertension (defined by the presence of varices or portosystemic collateral circulation). We also accessed the Fibrosis-4 index (FIB-4 - a product of the multiplication of age in years versus AST divided by platelets versus square root of ALT); Child-Pugh and MELD scores; aminotransferases and aminotransferase ratio, alkaline phosphatase, gamma glutamyl transferase, measured by enzymatic rate; prothrombin time/ international normalized ratio and platelets, assessed by automated method; albumin, bilirubin, measured by colorimetry; presence of antibodies (anti-smooth muscle, liver-kidney microsomal type 1 and antinuclear (assessed by indirect immunofluorescence); immunoglobulin G levels (measured by immunoturbidimetry), gamma globulin levels, as well as activity and fibrosis scores by METAVIR score at the first liver biopsy. The activity score is graded according to the intensity of inflammatory lesions: A1 = mild activity, A2= moderate activity, and A3 = severe activity. On the other hand, the grade of fibrosis is divided into F0 = no fibrosis, F1= portal fibrosis without septa, F2 = few septa, F3 numerous septa without cirrhosis, and F4 = cirrhosis.

The primary endpoints were one-year biochemical remission, histological remission, liver transplant, relapse, and death. We defined biochemical remission as the normalization of aminotransferase levels up to one year after diagnosis and histological remission as none or minimal periportal activity at the control biopsy performed after sustained normalization of laboratory exams [3]. Complete biochemical remission was defined as the combination of clinical and histological remission. Relapse was considered when the aminotransferases were elevated above three times the normal value after biochemical remission. The time from drug suspension to relapse was also recorded. To calculate the time to event, we used the start point of AIH treatment, and follow-up ended when the patient was lost, submitted to liver transplantation, or died.

2.1Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was done using SPPS 23.0 for Macbook (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Categorical variables were presented as a percentage. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov or Shapiro-Wilks tests were used to rank numeric variables regarding normal distribution. Those with normal distribution were reported with mean and standard deviation, while those with non-normal distribution were reported with median and width. The variables were compared using Mann-Whitney's U test, 'Student's T-test, or chi-square. Univariate analysis was done to determine variables associated with the outcomes, and results with p < 0.20 were further analyzed in multivariate analysis. Hosmer and 'Lemeshow's test and Nagelkerke R square were used to suit the logistic regression model. Kaplan-Meier curves were designed to evaluate general survival and transplant-free survival. Cox regression was applied to survival analysis when appropriate. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

2.2Ethical statementAll procedures were conducted following the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration, and the study was approved by the Federal University of Minas Gerais Ethics Committee Board (CAAE 80289917.7.0000.5149). Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of this study.

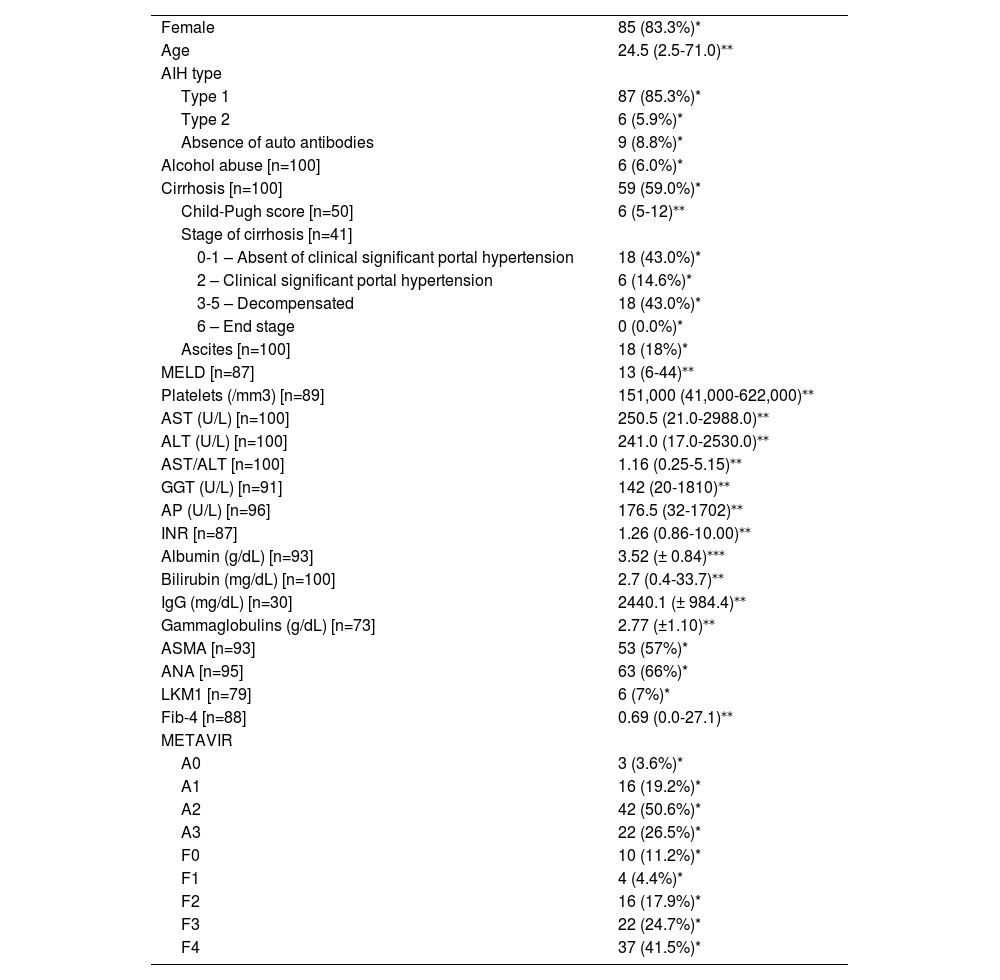

3ResultsThe overall cohort comprised 102 patients with clearly diagnosed AIH, of whom 80.3 % were women, with a median age at disease onset of 24.5 years (2.5–71.0 years). At diagnosis, 59 % of the patients presented with cirrhosis, most exhibiting clinically significant portal hypertension. Most showed significant alterations in aminotransferases, positive autoantibodies, moderate to severe inflammatory activity, and fibrosis upon biopsy. Table 1 summarizes clinical, laboratory, and histological features at AIH diagnosis.

Clinical features at disease onset (n=102)

| Female | 85 (83.3%)* |

| Age | 24.5 (2.5-71.0)⁎⁎ |

| AIH type | |

| Type 1 | 87 (85.3%)* |

| Type 2 | 6 (5.9%)* |

| Absence of auto antibodies | 9 (8.8%)* |

| Alcohol abuse [n=100] | 6 (6.0%)* |

| Cirrhosis [n=100] | 59 (59.0%)* |

| Child-Pugh score [n=50] | 6 (5-12)⁎⁎ |

| Stage of cirrhosis [n=41] | |

| 0-1 – Absent of clinical significant portal hypertension | 18 (43.0%)* |

| 2 – Clinical significant portal hypertension | 6 (14.6%)* |

| 3-5 – Decompensated | 18 (43.0%)* |

| 6 – End stage | 0 (0.0%)* |

| Ascites [n=100] | 18 (18%)* |

| MELD [n=87] | 13 (6-44)⁎⁎ |

| Platelets (/mm3) [n=89] | 151,000 (41,000-622,000)⁎⁎ |

| AST (U/L) [n=100] | 250.5 (21.0-2988.0)⁎⁎ |

| ALT (U/L) [n=100] | 241.0 (17.0-2530.0)⁎⁎ |

| AST/ALT [n=100] | 1.16 (0.25-5.15)⁎⁎ |

| GGT (U/L) [n=91] | 142 (20-1810)⁎⁎ |

| AP (U/L) [n=96] | 176.5 (32-1702)⁎⁎ |

| INR [n=87] | 1.26 (0.86-10.00)⁎⁎ |

| Albumin (g/dL) [n=93] | 3.52 (± 0.84)⁎⁎⁎ |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) [n=100] | 2.7 (0.4-33.7)⁎⁎ |

| IgG (mg/dL) [n=30] | 2440.1 (± 984.4)⁎⁎ |

| Gammaglobulins (g/dL) [n=73] | 2.77 (±1.10)⁎⁎ |

| ASMA [n=93] | 53 (57%)* |

| ANA [n=95] | 63 (66%)* |

| LKM1 [n=79] | 6 (7%)* |

| Fib-4 [n=88] | 0.69 (0.0-27.1)⁎⁎ |

| METAVIR | |

| A0 | 3 (3.6%)* |

| A1 | 16 (19.2%)* |

| A2 | 42 (50.6%)* |

| A3 | 22 (26.5%)* |

| F0 | 10 (11.2%)* |

| F1 | 4 (4.4%)* |

| F2 | 16 (17.9%)* |

| F3 | 22 (24.7%)* |

| F4 | 37 (41.5%)* |

Mean (± Standard deviation).

AIH: autoimmune hepatitis, MELD: Model of end-stage liver disease, AST: aspartate aminotransferase, ALT: alanine aminotransferase, GGT: gammaglutamyl transferase, AP: alkaline phosphatase, INR: international normalized ratio, ASMA: anti-smooth-muscle antibody, ANA: antinuclear antibody, anti-LKM1: liver-kidney microsomal antibody type 1, IgG: immunoglobulin G, A: inflammatory activity, F: fibrosis.

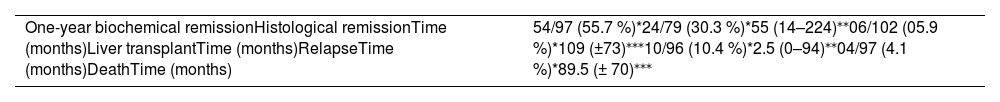

Table 2 outlines the endpoints evaluated in this study. The median follow-up time was 115 months, from 4 to 340 months. Univariate and multivariate analyses explored associations between clinical and laboratory variables and cirrhosis, ascites, and histological activity index at disease onset. Older age at disease onset correlated with cirrhosis (OR=1.099; 95 % CI: 1.008–1.198, p = 0.033). Higher AST/ALT ratio (OR=86.5; 95 % CI: 1.7–4399.1, p = 0.026) and increased MELD score (OR=1.58; 95 % CI: 1.07–2.33, p = 0.021) were associated with ascites. No association was found between clinical and laboratory features and histological inflammation at first biopsy after multivariate analysis.

Outcome rates and time occurrence in autoimmune hepatitis (n = 102).

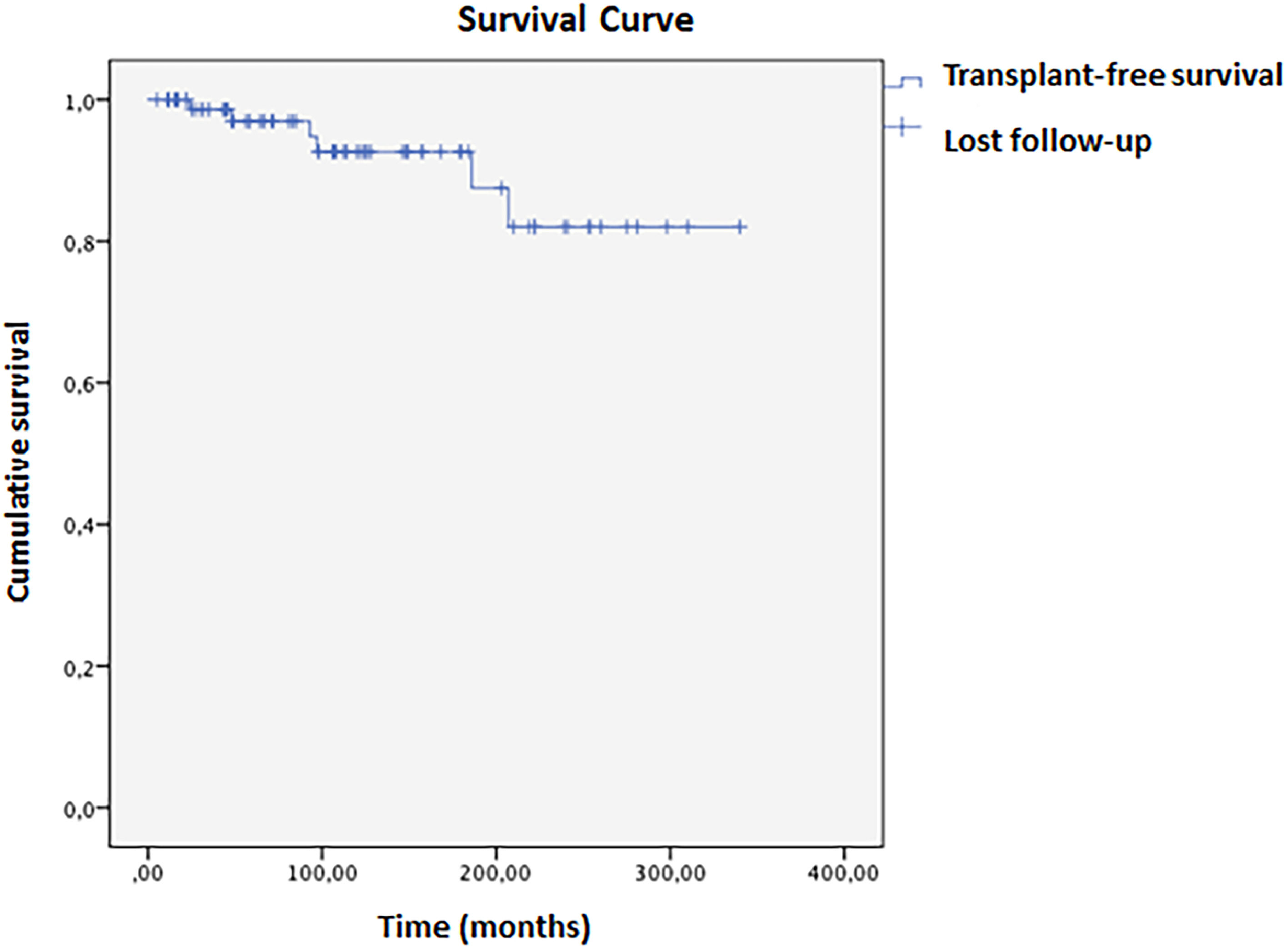

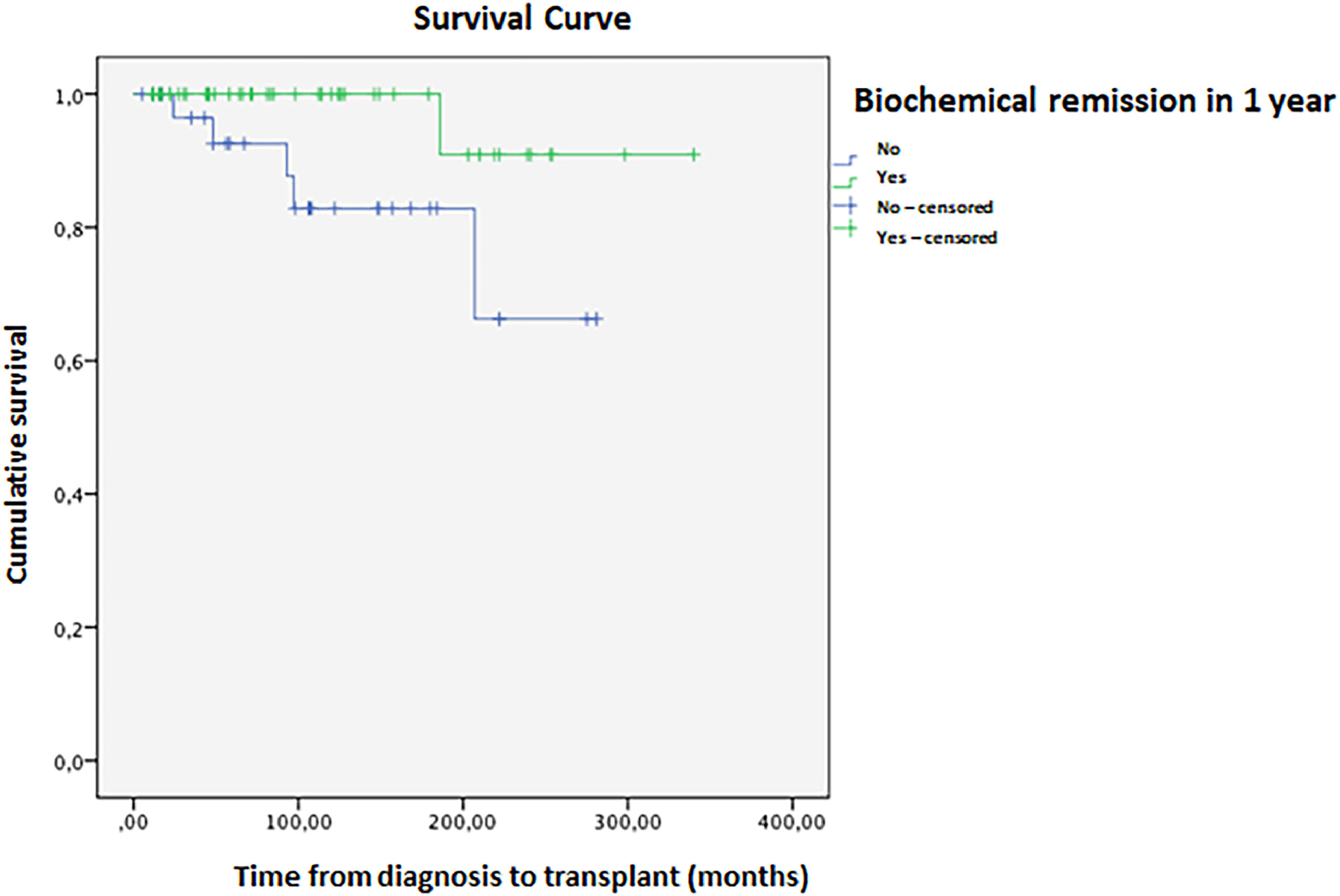

Biochemical remission one year after diagnosis occurred in 55.7 % of patients. Cirrhosis was associated with lower odds of remission (OR=0.263; 95 % CI: 0.073–0.952, p = 0.042). The histological remission rate was even lower at 30.3 %. In this population, 5.9 % required a liver transplant; one patient died 26 months post-procedure due to complications, while the other five remained alive without disease relapse. Mean transplant-free survival was 304 ± 13 months, with an 82 % cumulative rate at 336 months (Fig. 1). Biochemical remission within one year is associated with higher transplant-free survival (OR=0.139; 95 % CI: 0.055–0.354, p < 0.001). Kaplan-Meier analysis showed a significant difference between remission and non-remission groups (Log-rank p = 0.028, Breslow 0.021, Tarone-Ware p = 0.020). In 10 years, the cumulative survival of patients who met the criteria for biochemical remission was 99.82 %, compared to 87.21 % in those who did not, with a hazard ratio of 1.13 (Fig. 2).

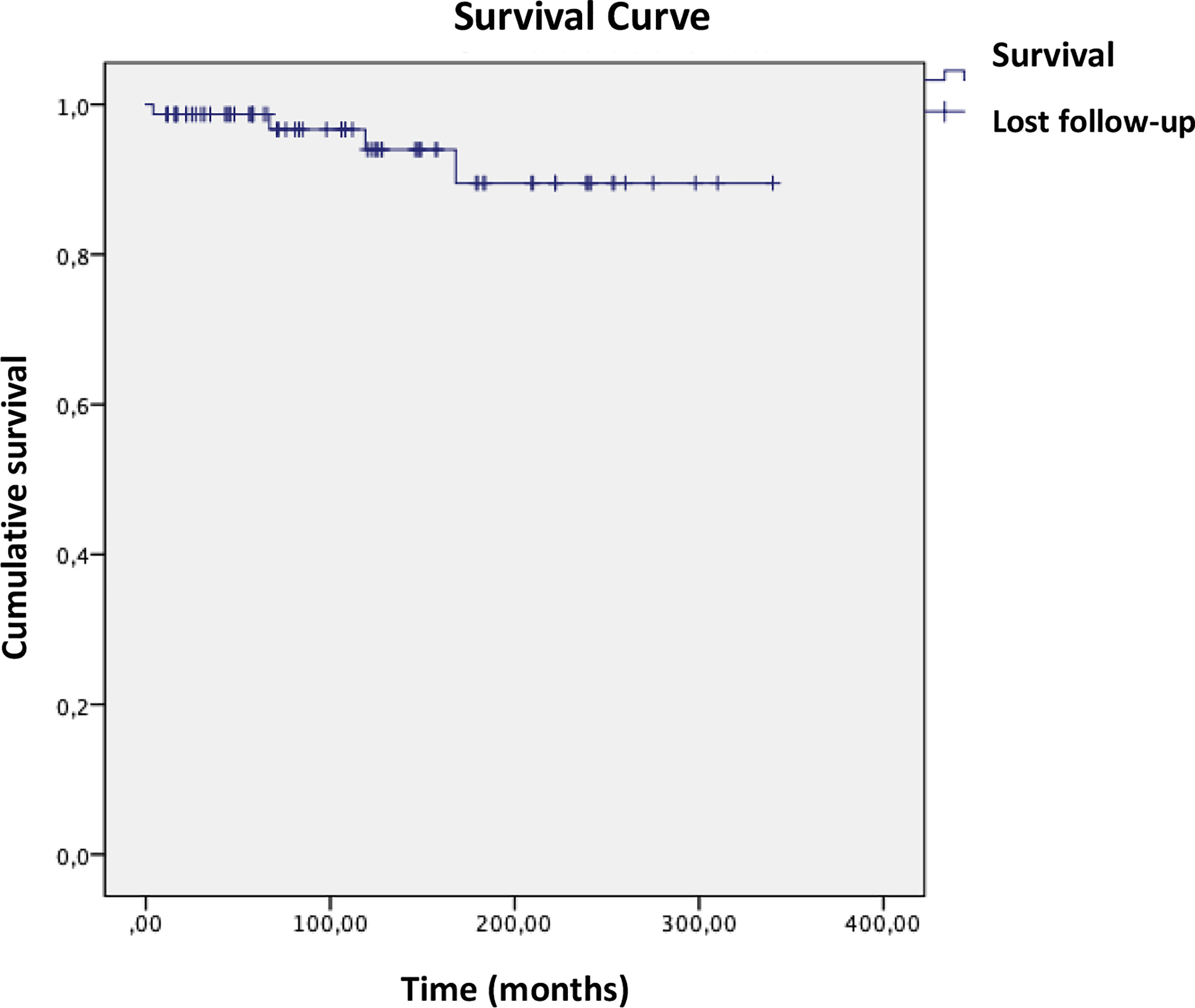

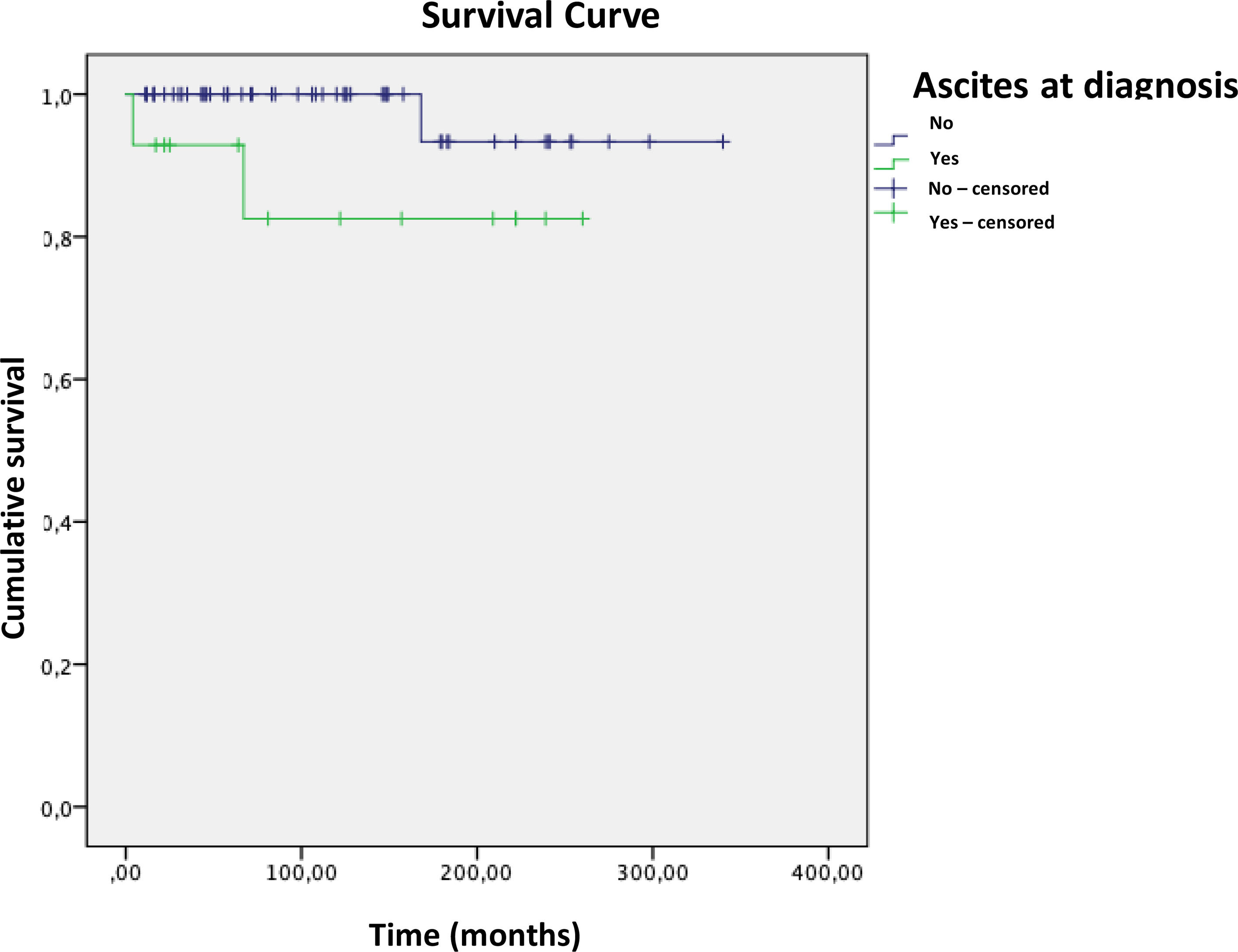

Complete remission (biochemical and histological) was achieved in 24 patients; 16 had treatment withheld, and nine relapsed within a mean time of 2.5 months. Four patients died during the study, with a mean survival of 316 ± 11 months (Fig. 3). Ascites at disease onset was associated with higher mortality (OR = 20.87; 95 % CI 1.07–404.43, p = 0.045). Kaplan-Meier curves indicated significant differences (Breslow 0.013, Tarone-Ware p = 0.022). Cox regression showed a mean survival difference of 7.17 months (95 % CI 0.64–66.59, p = 0.108) over 10 years, with cumulative survival at 98.4 % for those without ascites versus 89.4 % with ascites, and a Hazard ratio of 1.10 (Fig. 4).

4DiscussionThis study reports a high frequency of cirrhosis at disease onset, which was associated with older age and a reduced chance of achieving one-year biochemical remission. The biochemical and histological remission rates were lower compared to North American and European data, suggesting that AIH has an aggressive phenotype among Brazilians. [4,7] One-year biochemical remission was a protective factor for a liver transplant performed in 6 % of patients. Ascites at disease onset was associated with a higher AST/ALT ratio and elevated MELD score. The presence of ascites represented a significant increase in mortality rate by 20 times.

The female-to-male ratio was found to be 5:1, higher than the ratio reported in international literature of 2–4:1 [4,8]. A study conducted at 'King's College showed a better long-term prognosis and survival in male patients, while in Colombia, a higher proportion of men developed cirrhosis due to AIH [9,10]. Nevertheless, we did not find any association between gender and prognosis. The age variability was very wide, ranging from 2.5 to 71 years, showing that AIH diagnosis is possible regardless of age [5]. In South America, 76.5 % of patients are diagnosed under 25 years old, while in North America, the median age at diagnosis is 48 years old [11,12]. Interestingly, in our cohort, disease presentation concentrated at puberty and between the fourth and sixth decades of life and after the sixties [4].

In contrast with a cohort from São Paulo, our patients had lower bilirubin levels, which can be due to a less acute presentation of the disease and a lower prevalence of autoantibody positivity [12]. Type 1 AIH was the most common type in this study, mimicking a worldwide pattern. Unfortunately, the dosage of neither anti-SLA/LP nor HLA tests, known to impact the prognosis, was available [13–16].

A very high proportion of patients were diagnosed with AIH advanced liver disease (59 %), which can be associated with a delayed diagnosis or an aggressive disease presentation. Literature data regarding cirrhosis at disease onset is extremely variable according to the region studied. It ranges from 12 to 29 % in the US, Singapore and Europe to 62–76 % in Brazil and India. [3,17]. Despite the high rate of cirrhosis, most patients in our study were in the compensated stage and had a Child-Pugh score of A. Older age was associated with the presence of cirrhosis. Previous data showed an association between an increase in age and the presence of cirrhosis [18,19]. Cirrhosis was a predictor of poor biochemical response, although it did not impact histological remission or mortality [20]. The evaluation of histological remission in this context could have been impaired by the absence of a second biopsy due to contraindications or the intention to maintain immunosuppression.

The presence of ascites at disease onset was associated with a higher AST/ALT ratio and higher MELD scores. However, it is known that even decompensated cirrhosis with ascites is not a synonym for poor treatment response [21–24]. AST/ALT ratio >1 is a predictor of severe fibrosis and can be a marker in the follow-up of AIH [25]. Elevated MELD scores in British and American studies were predictors of poor treatment response and a worse prognosis [26,27]. In our study, neither the AST/ALT ratio nor MELD scores were associated with remission, liver transplant, or death.

Histologically, moderate to severe inflammation was not associated with clinical and laboratory variables. In 2013, a score based on laboratory exams was developed to predict the severity of inflammation at biopsy (Inflammatory score = 17 + (0.0047 x AST[U/L]) – (3.40 x albumin[g/dL]) – (0.4128 x total bilirubin total [mg/dL]) + (0.2527 x PCR[mg/dL])). A cutoff of 3.57 was accurate in predicting inflammation by the Histology Activity Index (≤4 and >4) with a sensitivity of 100 % and specificity of 85 % [28]. Nevertheless, it cannot replace liver biopsy, especially at diagnosis [4].

The one-year biochemical (55.7 %) and histological (30.3 %) remission rates were low but similar to the University of Sao Paulo cohort that reports 51.5 % and 36.2 %. [5] On the other hand, higher remission rates have been reported, such as 66–91 % and 25–80 % for biochemical and histological remission, respectively [3,29]. The lower rates of treatment response seen in Latin American studies of AIH may be attributed to several factors, including a higher prevalence of cirrhosis, more severe hepatitis, and younger age at onset. In addition, different susceptibility HLA alleles may present in this geographic region, which could also contribute to treatment outcomes [5]. The predictors of therapeutic response vary among studies. Some examples are bilirubin levels, INR, MELD, MELD-Na, UKELD, age at disease onset, HLA DR3, mean platelet volume, and anti-actin antibody. [12,26,27,30,31] On the other hand, a study conducted in Philadelphia did not show an association between antinuclear antibody and anti-smooth muscle antibody with the normalization of aminotransferases [32].

Liver transplant was performed in 6 % of patients in a median time of 9 years. As expected, one-year biochemical remission was a protective factor, reducing transplant needs by 86 %. The University of São Paulo's cohort of 268 patients followed up for seven years had a 10 % rate of liver transplantation, while in Peru and Argentina, AIH was responsible for 4 % to 7 % of pediatric and adult liver transplants [5,33]. These numbers might be overestimated since tertiary university centers concentrate on the most severe cases. In comparison, a British study that followed 245 patients for 36 years reported a much lower transplant rate of 4.5 % [34]. In our study, the transplant-free survival rate was 82 % in 336 months, while in an Italian cohort was 73.5 % in 280 months [35].

The relapse rate after treatment suspension was 56 %, and most of them occurred in the first three months of interruption. This frequency is similar to the 50–90 % rate reported in other studies [36]. During the follow-up, 4.1 % of the patients died. Ascites at disease onset was the only independent factor, elevating the chance of death by 20 times. In a Japanese cohort of 73 patients followed up for 27 years, the mortality rate was 11 % and both the AST/ALT and two-month biochemical remission were predictors of mortality [37].

There are limitations to this study that are inherent in its retrospective design, such as loss of follow-up and missing data. The lack of dosage of non-conventional autoantibodies and HLA testing is another weakness. However, this work's large sample size and the long follow-up observation period are important strengths. Furthermore, since AIH hepatitis is a rare disease with phenotypic presentation influenced by local genetic factors, retrospective studies are fundamental to understanding its natural history and generating new hypotheses to be prospectively tested.

5ConclusionsIn conclusion, we have shown that AIH presents an aggressive clinical phenotype in Brazilians, with high rates of cirrhosis at disease presentation and lower remission rates. This study highlights the need for early diagnosis and treatment, ideally in a pre-cirrhotic stage, to improve the chances of achieving biochemical remission. The significant association between ascites and mortality emphasizes the importance of monitoring patients for the development of ascites and prompt intervention if it occurs.

Overall, multicentric research is needed to understand better the prognostic factors of AIH in Brazil and Latin America. This will require increased funding, collaboration between researchers and healthcare providers, and the development of standardized diagnostic criteria and treatment guidelines for this condition in the region.

FundingThis research received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributionsConceptualization: L.R.G., G.G.L.C, F.M.F.O., L.C.F, C.A.C. Formal Analysis: L.R.G. Investigation: L.R.G., B.C.S., L.S.J. Writing – Original Draft Preparation: L.R.G., G.G.L.C., M.J.N. Writing – Review & Editing: L.R.G., G.G.L.C., L.C.F., C.A.C. Responsible for integrity: L.R.G.