Background: In the last decades it has been suggested that the main cause of liver cirrhosis in Mexico is alcohol. Currently in Western countries hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is one of the leading causes of endstage liver disease and liver transplantation. In Mexico, we have no data relative to the etiology of liver cirrhosis. The aim of this study was to investigate the main causes of liver cirrhosis in Mexico.

Methods: Eight hospitals located in different areas of the country were invited to participate in this study. Those hospitals provide health care to different social classes of the country. The inclusion criteria were the presence of either an histological or a clinical and biochemical diagnosis of liver cirrhosis.

Results: A total of 1,486 cases were included in this study. The etiology of liver cirrhosis was alcohol in 587 (39.5%), HCV 544 (36.6%), cryptogenic 154 (10.4%), PBC 84 (5.7), HBV 75 (5.0%) and other 42 (2.8). There was not statistical difference between alcohol and HCV.

Conclusions: We conclude that the main causes of liver cirrhosis in Mexico are alcohol and HCV.

The epidemiology of liver cirrhosis is characterized by marked differences between genders, ethnic groups, and geographic regions. The nature, frequency, and time of acquisition of the major risk factors for cirrhosis, namely hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus (HCV), and alcoholic liver disease, explain these variations.1

HCV infection is one of the leading causes of endstage liver disease requiring liver transplantation. Major centers report that approximately 25-30% of their candidate pools consist of HCV-infected patients.2 Approximately four million Americans are presently infected with the virus, and 20-30% of these patients can be expected to progress to cirrhosis.3 Donor availability is the most significant limiting factor for organ transplantation and leads to the use of less than perfect organs.

On the other hand, in the Dionysos study, which was carried out in the north of Italy to study the epidemiology of chronic liver diseases in the general population, the main risk factor for the development of liver cirrhosis was alcohol and the second factor was HCV.4 Excessive alcohol consumption is a social problem in Mexico. Frenk et al.5 have estimated that abuse of alcohol itself is related to approximately 9% of all disease in Mexico. Some diseases specifically associated with alcohol consumption, such as liver cirrhosis, result in reduced life expectancy. Campollo et al.,6 in a prospective study of 157 patients (48 women and 109 men) in the north of Mexico, found that alcoholism was the main cause for cirrhosis (38% in women and 95% in men) followed by viral causes. The alcoholic beverages consumed with greatest frequency were liquors such a tequila and others 96 degrees liquors. Since there appears to be an epidemiological transition for etiology of chronic liver diseases, the aim of this study was to investigate the main causes of liver cirrhosis in Mexico in this new century.

MethodsThe design of the study is cross sectional, multicenter and prospective. We studied a national sample of liver cirrhosis patients whose diagnosis has been obtained according to standardized criteria in different Mexican Hospitals, representative of the national health care systems. The following institutions participated to the study: Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (Centro Médico Nacional Siglo XXI, Centro Médico Nacional de Occidente and Hospital Regional de Durango), Instituto de Seguridad Social para los Trabajadores del Estado (Centro Médico Nacional “20 de Noviembre”), Secretaría de Salud Hospital General de México), Hospital Militar (Hospital Central), and a private hospital (Fundación Clínica Médica Sur). These hospitals are located in four Mexican states, are considered as being third level and provide health care to different social classes of the country. The main criteria for inclusion of a case in this study were an histological or clinical and biochemical diagnosis of record of liver cirrhosis. In all cases the histological diagnosis of cirrhosis was according with recommendations by the World Health Organization.7 The clinical and biochemical diagnosis (25% of the cases) was made when the liver biopsy was contraindicated for the presence of either abnormal coagulation indexes or thrombocytopenia according to the Guidelines to the British Society of Gastroenterology.8 The criteria used for the clinical and biochemical diagnosis of liver cirrhosis in all centers were clinical evidence at enrollment of complications of cirrhosis, i.e., ascitis, variceal bleeding, encephalophathy, or jaundice. Persistent elevations of biochemical liver tests.

Disease etiology, and patient’s gender and age were recorded. All cases were seen in the period from January 2000 to June 2002. The diagnosis of viral infections (B and C) were made by the positivity of HBsAg or Anti-HCV antibody. Liver cirrhosis due to alcohol was considered by history of ethanol consumption greater that 30 g/ day, and negativity to viral and autoimmune markers. To assesses daily alcohol intake we used the alcohol use disorders identification test from the World Health Organization.9 Cryptogenic cirrhosis was considered when the clinical history and laboratory data had failed to identify any recognizable cause. Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) made by the positivity of autoimmune markers (antimitochondrial antibodies). Patients with hemochromatosis, autoimmune, or metabolic disorders liver disease were considered in the groups of other causes.

Statistical analysisThe percentages of cases by etiology were compared using the c2 test, and the 95% confidence intervals were calculated. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.10

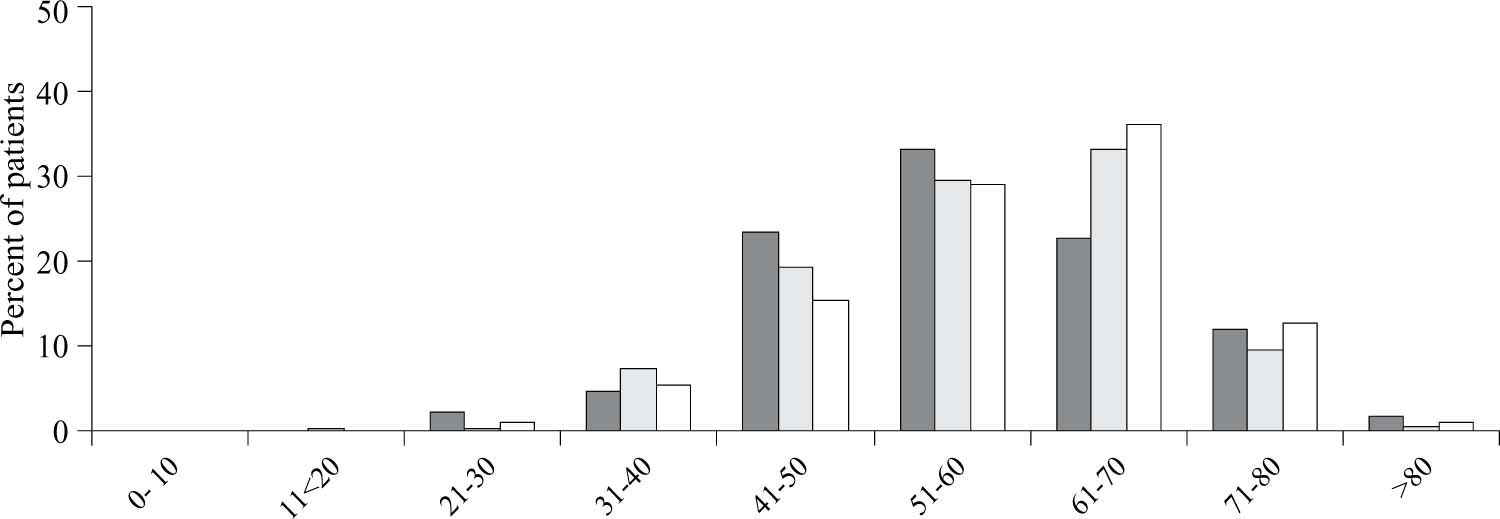

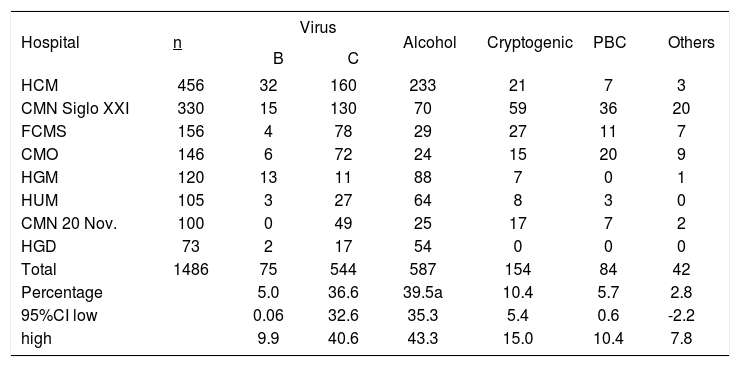

ResultsTable I shows the number of cases from each hospital and the etiology of liver cirrhosis. One thousand four hundred and eighty-six cases were included in this study, 727 (48.93%) were men and 759 (51.07%) women. Figure 1 shows the distribution by group of age and etiology. The main causes were alcohol in 587 cases (39.5%), and HCV in 544 cases (36.6%). There was no statistical difference between alcohol and HCV. Cryptogenic cirrhosis occurred in 154 cases (10.4%), and 90 of them were women. PBC in 84 cases,5,7 HBV in 75 cases (5.0%), and other causes (metabolic disorders of the liver, hemochromatosis and autoimmune hepatitis) in 42 cases (2.8%). In 72% of cases, the diagnosis of liver cirrhosis was made by liver biopsy and, in the remaining 27.8%, diagnosis was made on clinical and biochemical grounds.

Main causes of liver cirrhosis, by participating hospital.

| Hospital | n | Virus | Alcohol | Cryptogenic | PBC | Others | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | C | ||||||

| HCM | 456 | 32 | 160 | 233 | 21 | 7 | 3 |

| CMN Siglo XXI | 330 | 15 | 130 | 70 | 59 | 36 | 20 |

| FCMS | 156 | 4 | 78 | 29 | 27 | 11 | 7 |

| CMO | 146 | 6 | 72 | 24 | 15 | 20 | 9 |

| HGM | 120 | 13 | 11 | 88 | 7 | 0 | 1 |

| HUM | 105 | 3 | 27 | 64 | 8 | 3 | 0 |

| CMN 20 Nov. | 100 | 0 | 49 | 25 | 17 | 7 | 2 |

| HGD | 73 | 2 | 17 | 54 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 1486 | 75 | 544 | 587 | 154 | 84 | 42 |

| Percentage | 5.0 | 36.6 | 39.5a | 10.4 | 5.7 | 2.8 | |

| 95%CI low | 0.06 | 32.6 | 35.3 | 5.4 | 0.6 | -2.2 | |

| high | 9.9 | 40.6 | 43.3 | 15.0 | 10.4 | 7.8 | |

Non-significant vs HVC CMN Siglo XXI, Centro Médico Nacional Siglo XXI; CMO, Centro Médico de Occidente; HGM, Hospital General de Máxico; HCM, Hospital Central Militar; CMN 20 Nov, Centro Médico Nacional “20 de Noviembre”; HUM, Hospital Universitario de Monterrey; HGD, Hospital General de Durango; FCMS, Fundación Clínica Médica Sur.

In 2000, liver cirrhosis was the fourth leading cause of death in Mexico. More importantly, in the age group between 35 and 55 years, it was the second leading cause of death.11

The results of this study show that alcohol and HCV infection are the most frequent causes of liver cirrhosis in Mexico. Previous epidemiological studies carried out in Mexico have suggested that alcohol was the main cause of liver cirrhosis.12,13 Interestingly, in one of those studies,13 a significant correlation was found with the prevalence of spirits and pulque drinkers: with beer, the correlation was negative. The same group of investigators have analyzed the impact of alcohol on the incidence of liver cirrhosis mortality and showed a consistently high liver cirrhosis mortality rate over time. In addition, they observed a significant risk increment with age, with liver cirrhosis being the leading cause of death for both sexes in the 30–64 years age group.

Regarding HCV, it is estimated that there are approximately 170,000,000 persons infected with HCV.14 This is nearly 3% of the world population. In developed nations, prevalence rates of antibodies to HCV are generally less than 3%, whereas among volunteer blood donors they are less than 1%. In some highly endemic areas of the world (e.g., Egypt), the prevalence rates range from 10% to 30%.15 In the most highly endemic areas of the world, HCV infection is prevalent among persons older than 40 years, but is uncommon in those younger than 20 years.16,17

In Mexico, the prevalence rate of antibodies to HCV among volunteer blood donors is approximately 1.2%. This corresponds to nearly 1.2 million Mexicans infected with HCV, and 20-30% of these patients can be expected to progress to cirrhosis.18 In fact, the major long-term complications of chronic hepatitis C infection are cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, and hepatocellular carcinoma, which develop in a proportion of patients after many years or decades of infection.19,20 Progression to cirrhosis is often clinically silent, and some patients are not known to have hepatitis C until they present with the complications of end-stage liver disease or hepatocellular carcinoma. Once cirrhosis is present, the ultimate prognosis is poor.21

On the other hand, the third cause of liver cirrhosis in Mexico was cryptogenic cirrhosis. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is a chronic liver disease that is gaining increasing significance due to its large prevalence worldwide and the potential progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular failure.22-24 In a recent retrospective study that included 44 patients with cryptogenic cirrhosis,25 23 of them were actively followed up and were compared in a case-control study with viraland alcohol-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. These investigators found that the prevalence of obesity and diabetes was significantly higher in patients with cryptogenic cirrhosis, suggesting that some features of the metabolic syndrome present in this group may have a role in the mechanism of liver disease occurring in cryptogenic cirrhosis.25 Interestingly the prevalence of obesity in Mexico is very high.26 In this study, we have considered hemochromatosis in the group of other causes. In Mexico, hereditary hemochromatosis is very rare.27 In this study, we found two cases which were included in other causess. It has been suggested that hereditary hemochromatosis occurs worldwide, but is most common among individuals of northern European descent, particularly those of Nordic or Celtic origin.28 Cross-sectional studies of the frequency and distribution of the two HFE mutations in different populations have confirmed this association.29 In conclusion, in the present study, alcohol and hepatitis C were the main causes of liver cirrhosis. According to current information, in Mexico, the second most common cause of mortality in the age group between 35 and 55 years is liver cirrhosis. Since HCV infection is one of the leading causes of end-stage liver disease, and at the present time there is no vaccine for HCV, the prevention of HCV must focus on prevention of initial infection and elimination of infection through antiviral therapies.