Chronic hepatitis C (CHC) is the second cause of endstage liver disease in our country and one of the main indications of liver transplantation. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype is the principal prognostic factor and the determinant of the therapeutic scheme. In our country few data exist regarding the prevalence of HCV infection and genotype distribution in the Mexican Republic has not been determined. The aim of this study was to characterize the prevalence of the different HCV genotypes and to explore their geographical distribution. Methods: Mexican patients with hepatitis C infection, detected throughout the country between 2003 and 2006, were included. All samples were analyzed by a central laboratory and Hepatitis C genotype was identified by Line Immuno Probe Assay in PCR positive samples (Versant® Line Probe Assay Quest Diagnostics Nichols Institute, San Juan Capistrano CA). Data were analyzed according to the four geographical areas in Mexico. Results: One thousand three hundred and ninety CHC patients were included. The most frequent genotype detected was genotype 1 (69%) followed by genotype 2 (21.4%) and genotype 3 (9.2%). Genotype 4 and 5 were infrequent. There was no subject infected with genotype 6. Genotype 1 and 2 exhibit very similar distribution in all geographical areas. Genotype 3 infected patients were more frequent in the North region (52%) compared with other areas: center-western (30%), center (17%), South-South east (1%) (p < 0.001). Conclusions: The most prevalent HCV genotype in Mexico is genotype 1. Geographical distribution of HCV genotypes in the four geographical areas in Mexico is not homogenous with a greater frequency of genotype 3 in the north region. This difference could be related to the global changes of risk factors for HCV infection.

Liver cirrhosis and related disorders are a common cause of morbidity and mortality in Mexico. In fact, hepatic diseases have shown an incremental tendency during the last decades and in the last report of mortality of the National Statistics and Geographical Institute (INEGI) of 2005 they correspond to the fifth leading cause of general mortality and the fourth in men aged between 30 to 65 years, causing 30.209 deaths in this year.1 One study explored the trends in liver disease prevalence in Mexico from 2005 to 2050 through mortality data and found that an important increase will be expected during next decades.2 Hepatitis C infection is one of the most frequent etiologies of end-stage liver disease requiring liver transplantation around the world,3-5 and in Mexico it is the second most frequent cause of liver cirrhosis in the third level hospitals.6 In basis of several epidemiological studies it has been estimated that around 700,000 to 1.5 million of Mexicans are infected with hepatitis C virus.6-15 Hepatitis C genotype has been identified as the most important predictive factor of antiviral treatment response and current therapy is guided according to the infecting genotype.16 Information related to the virological characteristics of hepatitis C infection in our country is limited. The aim of the present study is to characterize the prevalence of different HCV genotypes and their geographical distribution in our population.

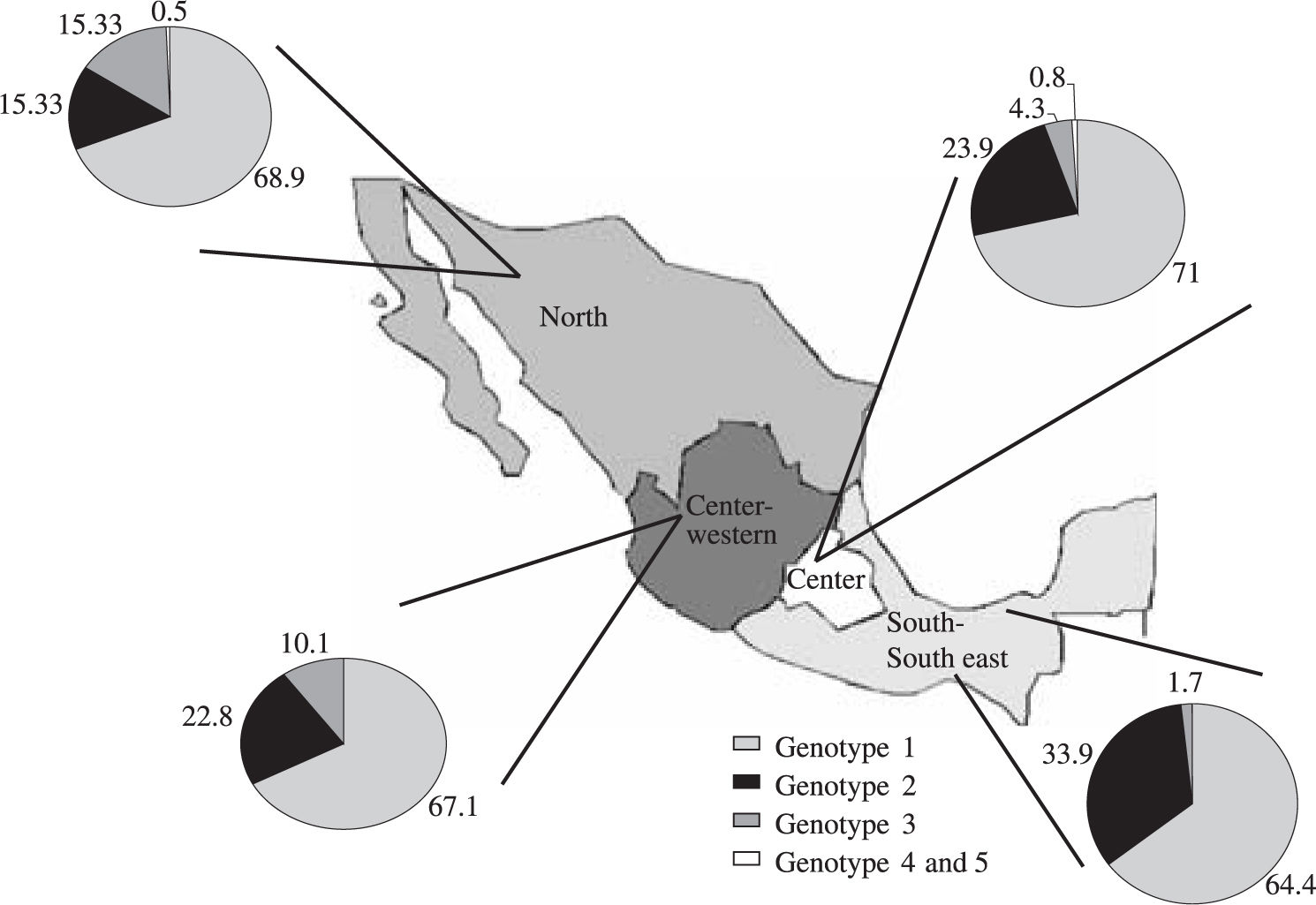

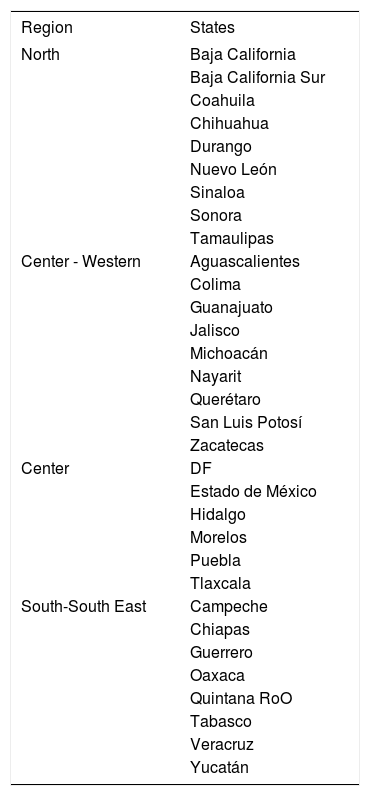

MethodsPatients with hepatitis C infection, identified as potentially candidates for antiviral treatment around our country detected between 2003 and 2006, were included. All samples were analyzed by a central laboratory (Quest Diagnostics Nichols Institute, San Juan Capistrano CA). Hepatitis C genotype was identified by Line Immuno Probe Assay in PCR positive samples (Versant® Line Probe Assay Quest Diagnostics Nichols Institute, San Juan Capistrano CA). Data were analyzed by political and geographical distribution according to the four geographic areas in Mexico: North region (includes Baja California Norte, Baja California Sur, Coahuila, Chihuahua, Durango, Nuevo León, Sonora and Tamaulipas), Centre-Western region (includes Aguascalientes, Colima, Guanajuato, Jalisco, Michoacán, Nayarit, Querétaro, San Luis Potosí and Zacatecas), Central region (includes Distrito Federal, Hidalgo, México, Morelos, Puebla and Tlaxcala) and South-southeast region (includes Campeche, Chiapas, Guerrero, Oaxaca, Quintana Roo, Tabasco, Veracruz and Yucatán) (Table I). Descriptive data were presented as a percentage or mean with standard deviation and range. The ϰ2 test was used to compare homogeneity between groups per region and genotype.

The four geographical areas of Mexico.

| Region | States |

|---|---|

| North | Baja California |

| Baja California Sur | |

| Coahuila | |

| Chihuahua | |

| Durango | |

| Nuevo León | |

| Sinaloa | |

| Sonora | |

| Tamaulipas | |

| Center - Western | Aguascalientes |

| Colima | |

| Guanajuato | |

| Jalisco | |

| Michoacán | |

| Nayarit | |

| Querétaro | |

| San Luis Potosí | |

| Zacatecas | |

| Center | DF |

| Estado de México | |

| Hidalgo | |

| Morelos | |

| Puebla | |

| Tlaxcala | |

| South-South East | Campeche |

| Chiapas | |

| Guerrero | |

| Oaxaca | |

| Quintana RoO | |

| Tabasco | |

| Veracruz | |

| Yucatán |

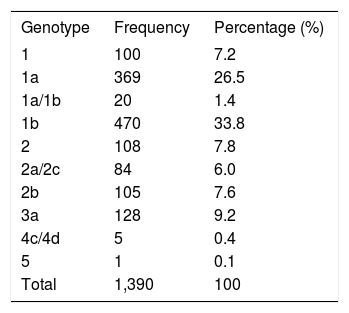

One thousand three hundred and ninety patients with a mean age of 47.8 ± 12.9 years (range 17-83) were included. Fifty nine percent of them were females and the mean of body weight was 70.6 kg ± 13.2 kg (range: 35.6123 kg). The most frequent genotype infecting Mexican patients was genotype 1 accounting for 69% of the cases, and among them subgenotype b was the most prevalent with 33.8% (Table II). Around one fourth of our study population was genotype 2 (21.4%), followed by frequency by genotype 3 (9.2%). Genotype 4 and 5 were infrequent. In our group there was no patient with genotype 6.

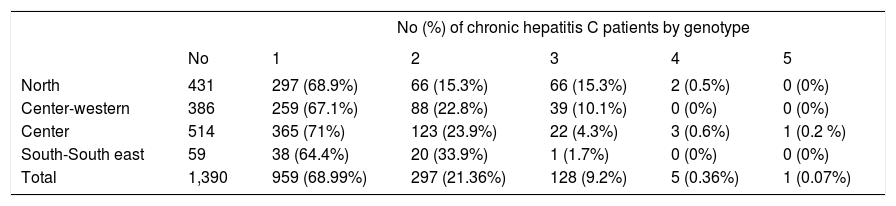

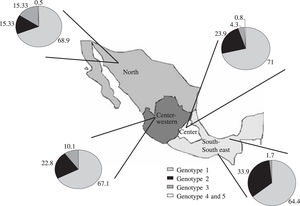

Distribution of genotypes according to the four geographical areas in Mexico is shown inTable III. The percentage of patients with genotype 1 was very homogenous in the country, being between 64 to 71%. Similarly, genotype 2 was distributed in all areas with percentages of 15.3 to 33.9%. When we divided the population by genotype and observed their distribution we noticed that most of genotype 3 patients are located in north area with 52% of infected subjects (p < 0.001) (Table III and Figure 1). To confirm that this difference was due to area and genotype and not to the different sample size in each region we selected the three most prevalent genotypes and a ϰ2 was performed obtaining consistent results (Table IV).

HCV genotypes in 1,390 Mexican chronic hepatitis c patients according to geographical area.

| No (%) of chronic hepatitis C patients by genotype | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| North | 431 | 297 (68.9%) | 66 (15.3%) | 66 (15.3%) | 2 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Center-western | 386 | 259 (67.1%) | 88 (22.8%) | 39 (10.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Center | 514 | 365 (71%) | 123 (23.9%) | 22 (4.3%) | 3 (0.6%) | 1 (0.2 %) |

| South-South east | 59 | 38 (64.4%) | 20 (33.9%) | 1 (1.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Total | 1,390 | 959 (68.99%) | 297 (21.36%) | 128 (9.2%) | 5 (0.36%) | 1 (0.07%) |

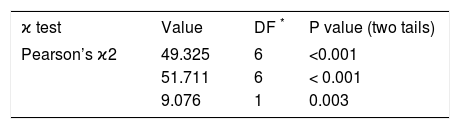

Statistic analysis for HCV genotypes homogeneity per region.

| ϰ test | Value | DF * | P value (two tails) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson’s ϰ2 | 49.325 | 6 | <0.001 |

| 51.711 | 6 | < 0.001 | |

| 9.076 | 1 | 0.003 |

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a major cause of liver disease worldwide with a large spectrum including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma and a potential cause of substantial morbidity and mortality in the future.3-5 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates a prevalence of 3% with the virus affecting 170 million people around the world.17 The complexity and uncertainty related to the geographic distribution of HCV infection and chronic hepatitis C, determination of its associated risk factors, and evaluation of cofactors that accelerate its progression, underscore the difficulties in global prevention and control of HCV and makes global disease burden estimation a difficult issue.4,18 At present moment, in our country accurate population statistics and national survey studies are lacking. The prevalence of 0.7 to 1.5% has been estimated according to the WHO data and based on multiple epidemiological reports, however they represent selected populations and specially volunteer blood donors.6-15 Although accurate HCV epidemiological data are missing, there is no doubt that end stage liver disease constitutes the fifth leading cause of global mortality in Mexico.1 One recent publication suggest that chronic hepatitis C is the second most frequent etiology of liver cirrhosis making CHC a real public health issue in our population.6 Because the direct measurement of HCV infection incidence is impractical, researchers have relied upon mathematical models to infer trends in incidence, morbidity and mortality. In Mendez-Sanchez et al study, mathematical projection based on mortality data suggests that liver disease will be an increasing cause of mortality in Mexico during next decades.2

HCV is divided among six genotypes with numerous subtypes.19 These genotypes show a difference up to 30% from each other in nucleotide sequence. According to HCV genotype, length of treatment and dosage of antiviral therapy can differ.16 Alpha-interferon based therapy achieve sustained virological response with less success in genotype 1b compared to genotypes 2 and 3. It is therefore important to track the different genotypes of the HCV virus. In the United States, the NHANESIII study report that 56.7% of the infected patients were classified as 1a, 17% as 1b, 3.5% as 2a, 11.4% as 2b, 7.4% as 3a, 0.9% as 4, 3.2% as type 6.20 In England 50% of all HCV infected subjects were genotype 1 with a higher percentage of genotype 3 among the IVDU population.21 In fact genotype 1b was the predominant genotype in Chile, Japan and in most of western countries.3,4,22,23 In contrast genotype 2 and 3 are prevalent in the Indian subcontinent and China, genotype 4 is the most common genotype in Africa and the Middle East, genotype 5 can be found in South Africa and genotype 6 in south-east Asia.3,4,24

This study constitutes the largest series published in chronic hepatitis C infected Mexican patients. It confirms, as expected for our geographical situation, that the most prevalent genotype infecting our CHC subjects is genotype 1 with almost 70%, followed by genotype 2 and 3. The frequency of genotype 4 and 5 was very low and we didn’t detect any case with genotype 6. One remarkable finding is that genotype distribution in our country is different among the four geographical regions (division stated by our National Statistics and Geographical Institute) with more than half of genotype 3 in the North area. This situation could have an explanation in the well known change in epidemiology risk factors occurring worldwide. Most epidemiological studies conducted in Mexico concluded that history of blood -or derivates-transfusion before 1995 was the main risk factor for HCV infection. One recent multicentric study form Vera de León et al, although support past blood transfusion as the leading probable cause of HCV acquisition in 64.2% of patients, stress intravenous illicit drug usage (IDUs) as an important risk factor for HCV infection in persons who live in north Mexico states, factor that was present in 54.2% of them and 69% of male cases.25 In many other studies, HCV infection with genotype 3 has been identified with high prevalence within IDUs specially in developed countries.25-27 According to National Council against addictions (CONADIC) there has been an increase in illicit drug usage among Mexicans, more important in male gender, in the Mexico-United States border and in large cities.28 This increasing IDUs in the north of our country could be related with the high HCV genotype 3 prevalence found in present study. Since 1994 our national regulation adopted HCV testing as mandatory in the screening for blood transfusion and the risk of HCV infection related to transfusion has dropped to levels considered as low as in most of developed countries; excluding those patients with transfusion history before this year, transfusion could account for less than 5% of HCV infected population that receives medical attention in many Mexican hospitals.25,29 These observations suggest that HCV epidemiological pattern is evolving and implications related to this change should be considered in our future medical attention and public health policies.

ConclusionsIn this large study conducted in Mexican patients with chronic hepatitis C we found that genotype 1 was the most prevalent. There was a non-homogenous distribution of genotypes among the four geographical areas of our country, with a high proportion of genotype 3 infected subjects in the north of the Mexican Republic. It suggest that, similarly in other countries, risk factors related to HCV infection acquisition are changing, patterns that could implicate relevant modifications in our future medical and public policies focused in the improvement of the attention of HCV infected patients.

This study was performed with an unrestricted support of Schering Plough S.A de C.V. México.