Endometriosis is the abnormal existence of functional uterine mucosal tissue outside the uterus. It is a usual disorder of women in reproductive age which is mainly located in the female genital tract. Hepatic endometriosis is one of the rarest disorders characterised by the presence of ectopic endometrium in the liver. It is often described as cystic mass with or without solid component. Preoperative diagnosis is difficult via cross-sectional imaging and histopathologic evaluation remains the gold standard for diagnosis. We report an asymptomatic 40-year-old female with a large cystic mass involving the left hepatic lobe. She underwent laparoscopic removal of the cyst. The diagnosis of hepatic endometriosis was established by the histopathological analysis of the surgical specimen.

Endometriosis is the abnormal existence of functional uterine mucosal tissue outside of the uterine cavity and musculature while extrapelvic endometriosis refers to endometriosis found at body sites other than the pelvis.1 It is a benign condition most commonly noted in the uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, and local pelvic peritoneum. However, endometriotic lesions have also been described in almost all other remote organs of the human body, including the omentum, gastrointestinal tract, peritoneum, operative scars, lymph nodes, umbilicus, skin, lungs, pleura, bladder, kidneys, pancreas, and even in males.1

Hepatic endometriosis, one of the rarest forms of atypical endometriosis, was first described in 1986.2 To our knowledge, only 26 cases of hepatic endometriosis have been previously reported in the literature. We herein report an extremely rare case of hepatic endometriosis and evaluate the current literature addressing the diagnosis focusing on advances in the clinical manifestation, pathogenesis, and diagnostic workup.

Case PresentationA 40-year-old female patient initially presented with an incidental finding of a cyst in the left lobe of the liver in a routine ultrasound (US) examination. She denied pain and previous medical history. She had two normal labours in the past. She had no further gynaecological history and her menstrual cycle was normal.

The US revealed a large cystic lesion between the left and the right lobe of the liver, expanding towards the hilum of the liver and the gallbladder. Complete blood count and biochemical blood tests were normal. Echinococcal antibodies were also negative.Blood results showed a slight increase of the hepatic enzymes; SGPT: 79IU/L, SGOT: 40IU/L, yGT: 76IU/L. Serological tests for hepatitis B surface antigen and anti-hepatitis C virus antibodies were negative. The tumor markers (CEA, CA 19-9, AFP, CA 125) were normal and echinococcal antibodies were negative as well.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed and revealed a multiseptated cystic lesion 10.3 × 7.8 × 7.7 cm in the left liver lobe and specifically in segments IV, II and III (Figure 1). The septa were with high density thick walls and the larger space was found the anterior aspect of the cyst (Figure 2). No haemorrhagic or solid findings were revealed and no lymph node involvement was described.

The patient underwent a laparoscopic surgical removal of the cyst. The pelvis was examined and no evidence of endometriosis was found. No other abnormalities were observed during the operation. The patient had an uneventful postoperative course and was discharged on the seventh postoperative day.

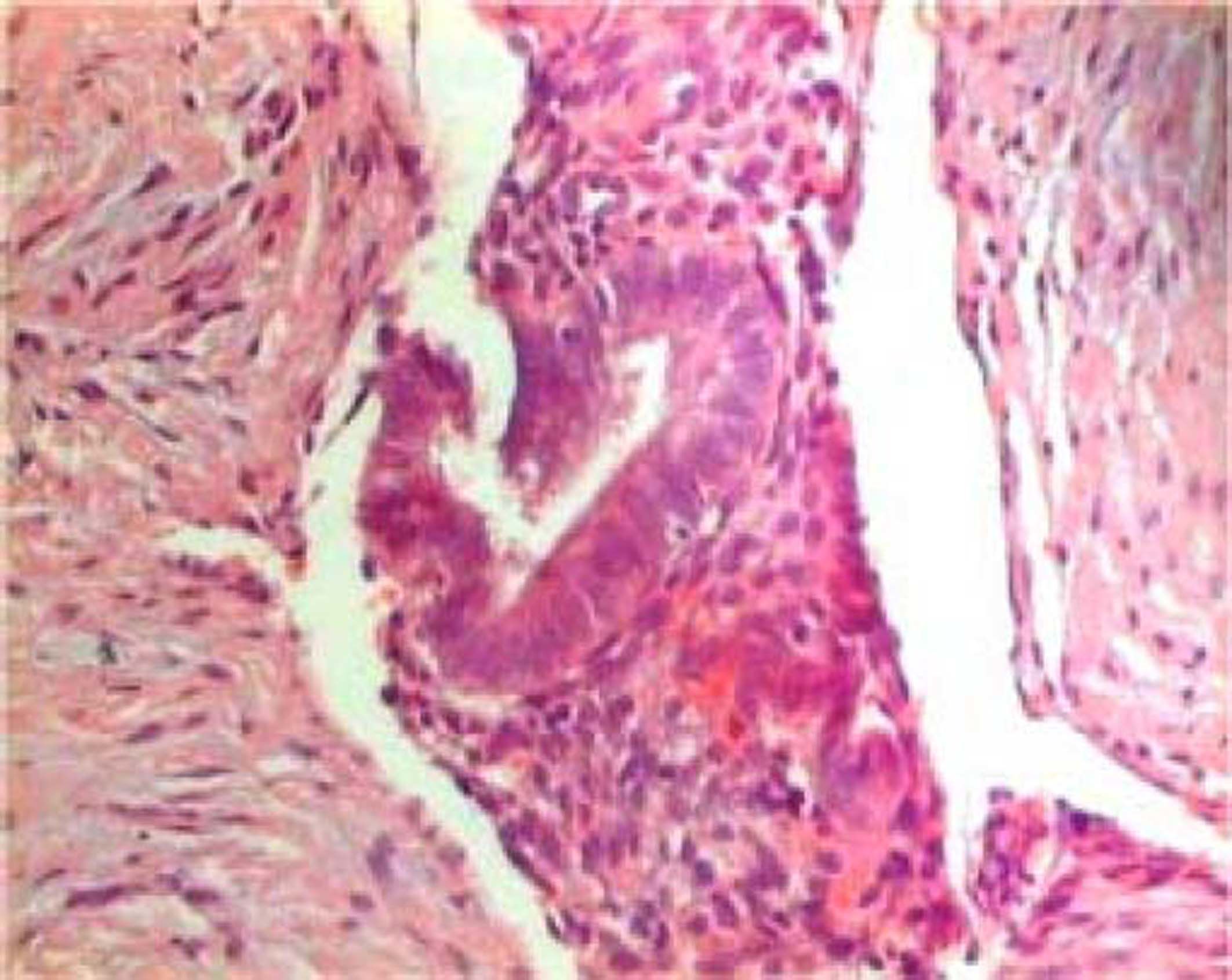

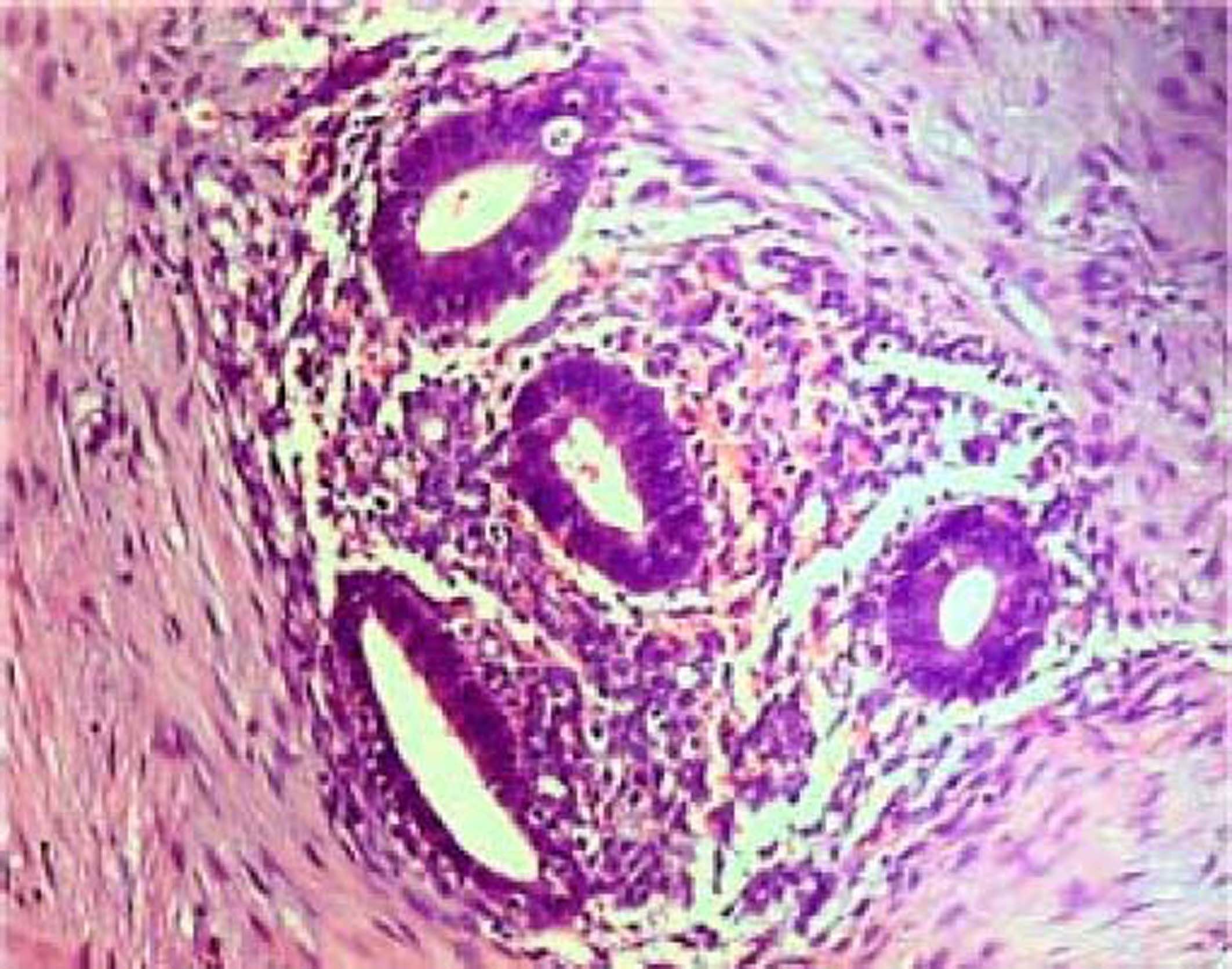

Histopathologic evaluation confirmed hepatic endometriosis. While the surrounding liver tissue was normal, immunostaining of the cyst showed CK7+ (in glandular tissue), CD10+ and ER+ (in endometrial stroma) (Figures 3 and 4).

Endometriosis is approximately estimated to effect 10-15% of women in reproductive age with a mean age of presentation of 31.7-34 years, and up to 50% of infertile women.3 Endometriosis usually involves the ovaries, the uterine tube, the uterus, the vagina, the cervix, the vulva, the sacro uterine ligament, the teres ligament and the rectovaginal septum. Extrapelvic endometriosis has an incidence which represents 8.9% of reported cases of endometriosis.1,4 It may involve peritoneum, the urinary bladder and the ureter, the lungs, the gallbladder, the breasts, the extremities, the colon and the rectum. Hepatic endometriosis, first described by Finkel, et al.,5 is an extremely rare disorder characterized by the presence of ectopic endometrial tissue in the liver.

The mechanism by which extrauterine endometriosis is involved remains unknown. Various theories have been proposed to identify the pathogenesis of endometriosis; considering all the theories proposed each satisfies only some of the reported cases. Two major theories involve either the implantation of endometrial cells (implantation theory) or the metaplasia of the peritoneal epithelium (coelomic metaplasia theory) in the region of occurrence.6

The metaplasia of (peritoneal) epithelium due to chronic inflammation or an unknown signaling cascade may be better suited to explain the occurrence of endometriosis in obscure locations, such as in the heart or even the male.

The implantation theory suggests that endometrial tissue is transplanted into the peritoneum and pelvic organs through retrograde menstruation, hematogenous and/or lymphatic dissemination, or iatrogenic injury. This theory could explain intraparenchymal cases of hepatic endometriosis because demonstrates the presence of endometrioid cells in lymphatic vessels or locoregional lymph nodes in patients with infiltrating endometriosis.7

Retrograde menstruation is believed to cause transcoelomic spread and implantation within the pelvis due to its predilection for gravity-dependent pelvic deposits in most observed lesions. This theory proposed the potentiality of microenvironment of the peritoneum to change connective tissue to endometrial tissue. However, this theory cannot explain distant and intraparenchymal lesions.6

In our case, no relation was found between the hepatic cyst and peritoneal surface, refusing the coelomic metaplasia theory. The absence of previous history of endometriosis for our patient makes the implantation theory unlikely. The presence of hepatic parenchyma lesion in our case could be better explained by lymphovascular spread of endometriosic cells. The liver might be a transportation target of endometrial fragments by lymphatic or blood vessels.

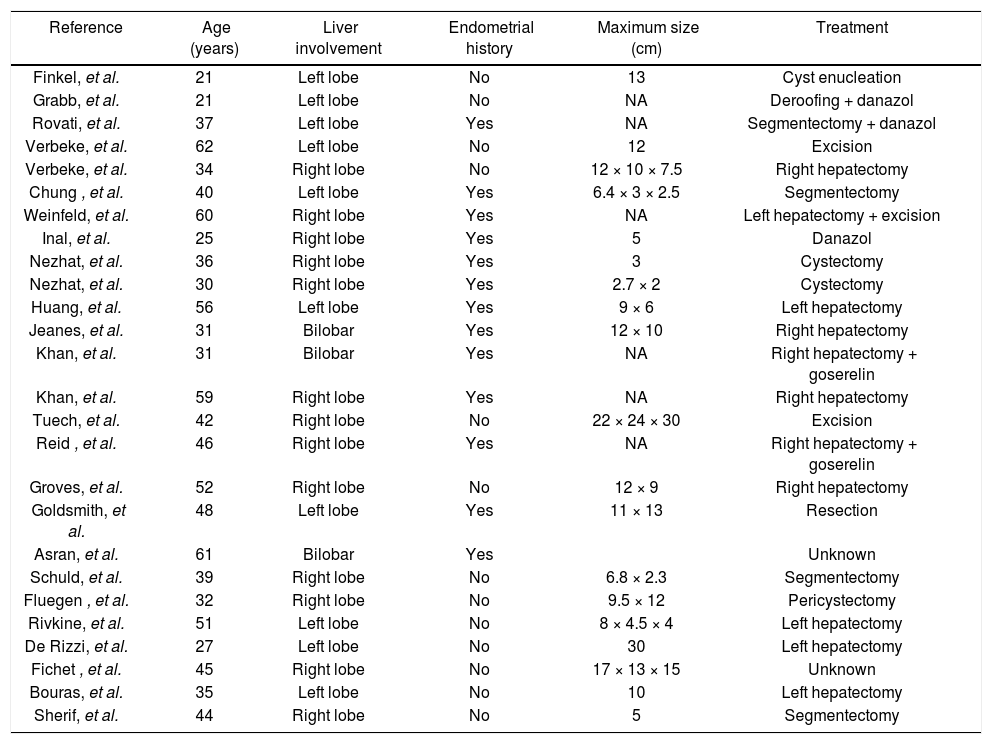

Reviewing the current English literature, we revealed only 26 cases of hepatic endometriosis and summarized the clinical and pathological features of them (Table 1). Diagnosis is difficult and often made years after the onset of symptoms, because only few patients presented characteristic cyclic pain related with menses. US, CT and MRI are helpful but no typical image of endometriosis cyst has been described. No specific diagnostic markers may be sufficient to isolate hepatic endometriosis from hepatic lesions. The final diagnosis can be made only by histological evaluation. The differential diagnosis includes both benign conditions, as echinococcal cyst, abscess, hematoma, cystadenoma, and malignant cystic neoplasm, as cystadenocarcinoma or metastatic disease. Furthermore, hepatic endometrioma should always be considered in the differential diagnosis for a woman of any age presenting with a hepatic mass, with or without previous endometriosis history. In our case, we performed a laparoscopic exploration; the advantages of laparoscopic procedure were the possibility of identifying other abdominal tissue deposits and avoiding a useless laparotomy in case of an advanced malignancy or generalised carcinomatosis.

Clinical and pathological features of reported cases of hepatic endometriosis.

| Reference | Age (years) | Liver involvement | Endometrial history | Maximum size (cm) | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finkel, et al. | 21 | Left lobe | No | 13 | Cyst enucleation |

| Grabb, et al. | 21 | Left lobe | No | NA | Deroofing + danazol |

| Rovati, et al. | 37 | Left lobe | Yes | NA | Segmentectomy + danazol |

| Verbeke, et al. | 62 | Left lobe | No | 12 | Excision |

| Verbeke, et al. | 34 | Right lobe | No | 12 × 10 × 7.5 | Right hepatectomy |

| Chung , et al. | 40 | Left lobe | Yes | 6.4 × 3 × 2.5 | Segmentectomy |

| Weinfeld, et al. | 60 | Right lobe | Yes | NA | Left hepatectomy + excision |

| Inal, et al. | 25 | Right lobe | Yes | 5 | Danazol |

| Nezhat, et al. | 36 | Right lobe | Yes | 3 | Cystectomy |

| Nezhat, et al. | 30 | Right lobe | Yes | 2.7 × 2 | Cystectomy |

| Huang, et al. | 56 | Left lobe | Yes | 9 × 6 | Left hepatectomy |

| Jeanes, et al. | 31 | Bilobar | Yes | 12 × 10 | Right hepatectomy |

| Khan, et al. | 31 | Bilobar | Yes | NA | Right hepatectomy + goserelin |

| Khan, et al. | 59 | Right lobe | Yes | NA | Right hepatectomy |

| Tuech, et al. | 42 | Right lobe | No | 22 × 24 × 30 | Excision |

| Reid , et al. | 46 | Right lobe | Yes | NA | Right hepatectomy + goserelin |

| Groves, et al. | 52 | Right lobe | No | 12 × 9 | Right hepatectomy |

| Goldsmith, et al. | 48 | Left lobe | Yes | 11 × 13 | Resection |

| Asran, et al. | 61 | Bilobar | Yes | Unknown | |

| Schuld, et al. | 39 | Right lobe | No | 6.8 × 2.3 | Segmentectomy |

| Fluegen , et al. | 32 | Right lobe | No | 9.5 × 12 | Pericystectomy |

| Rivkine, et al. | 51 | Left lobe | No | 8 × 4.5 × 4 | Left hepatectomy |

| De Rizzi, et al. | 27 | Left lobe | No | 30 | Left hepatectomy |

| Fichet , et al. | 45 | Right lobe | No | 17 × 13 × 15 | Unknown |

| Bouras, et al. | 35 | Left lobe | No | 10 | Left hepatectomy |

| Sherif, et al. | 44 | Right lobe | No | 5 | Segmentectomy |

The natural history of hepatic endometriosis is unknown due the lack of published prospective follow-up studies. Resection of cystic endometriosis should be considered in symptomatic patients. The clinical presentation of the disease can be associated with symptoms such as pelvic pain, dyspareunia, infertility, or it may be asymptomatic and incidentally discovered8 like our case. Medical history regarding upper abdominal pain associated with the onset of the menstrual cycle should be evaluated. However, this is not the most common manifestation of the hepatic endometriosis as has been established in the cases reported in the literature. Excluding one, all patients described in the literature had epigastric or right upper quadrant pain; and only two patients complained of characteristic cyclic pain related with menses.8 Also, six patients were postmenopausal showing that this condition is not limited to reproductive age women.

The management strategy of hepatic endometriosis is difficult to be recommended for this group of patients. When the patient is symptomatic, the need for treatment is clear. However, it remains undetermined whether asymptomatic patients should be treated to prevent the potentially severe and debilitating complications that can occur if the endometriotic lesions deeply infiltrate the liver. Furthermore, although malignant transformation of endometriosis is a rare event, occurring commonly in the ovary, cases of sarcoma and adenocarcinoma arising from endometriosis of the liver have been described.9,10 On the other hand, the hormonal management with progestogens and gonadotropin releasing hormone analogues may reduce the symptoms but has short term success and carries the risk of side effects and long-term dependence on medication.11

ConclusionHepatic endometriosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a cystic liver mass despite conducting exhaustive investigations in the absence of characteristic clinical and radiological features. Histological examination is essential, and surgery remains the treatment of choice. Currently, there are no reports in the literature regarding complications arising from the progression of hepatic endometriosis. However, this lack of evidence does not deny its existence.