Background and rationale. Epidemiologic research suggests that physical activity (PA) reduces the risk of chronic diseases including gallstones. Objective. This study explores the association between recreational physical activity (RPA) and risk of asymptomatic gallstones (AG) in adult Mexican women.

Material and methods. We performed a cross-sectional analysis of women from the Health Workers Cohort Study. The study population included Mexican women aged 17-94 years, with no history of gallstone (GS) or cholecystectomy. A self-administered questionnaire was used to collect information on weight change, gynecological health history, cholesterol-lowering medications and diuretics, history of diabetes mellitus type 2 (DM2), PA and diet. PA was calculated in minutes/day, minutes/week and Metabolic Equivalents (METs)/week. Gallstone diagnosis was performed using real-time ultrasonography. The association between RPA and risk of AG was evaluated using multivariate logistic regression models.

Results. Of the 4,953 women involved in the study, 12.3% were diagnosed with AG. The participants with AG were significantly older, had a higher body mass index, and had a higher prevalence of DM2 than those without AG. The participants with > 30 min/day of RPA had lower odds of AG (OR = 0.80; 95% CI: 0.65-0.97; P = 0.03), regardless of other known risk factors for gallstone disease. Furthermore, we observed an inverse relationship between RPA time and AG risk, especially in women doing more than 150 min a week of RPA (OR = 0.76; 95%CI: 0.61-0.95; P = 0.02).

Conclusion. These findings support the hypothesis that RPA may protect against AG, although further prospective investigations are needed to confirm this association.

Asymptomatic gallstones (AG) are being diagnosed increasingly, mainly as a result of the widespread use of abdominal ultrasonography for the evaluation of patients for unrelated or vague abdominal complaints and in cases of routine checkup.1 Additionally, a minority of people with AG, eventually may develop major gallstones complications, however the majority of gallstones remain asymptomatic and costs and risks of prophylactic cholecystectomy exceed the benefits. For this reason, expectant management is an appropriate choice for AG in the general population.1,2

In Western countries, gallstone disease (GD) is one of the main causes of adult morbidity and hospitalization, causing high healthcare costs.1 For example, twenty percent of adults in the United States carry gallstones (GS), among them 50-70% are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis;2 and 6.5 billion dollars are spent annually3 on around 800,000 related hospitalizations per year.4 Certain US subpopulations have even higher rates of GS. for instance, 70% of Pima Indians older than 50 suffer from GS, as do 22.1% of Mexican-American women.5 A Mexican study using ultrasound diagnosis found that adults aged 35-64 had a GS prevalence of 11.2%, which rose to 19.7% among female participants.6 Researchers estimate that around 150,000 cholecystectomies related to GS occur in Mexico each year.6 Risk factors such as being female,7 being obese or having central obesity,8 experiencing a high number of pregnancies9 and the presence of diabetes mellitus7 are believed account for the higher prevalence of GS among women in Mexico.

Research suggests that physical activity (PA) mitigates chronic disease risk,10–14 including the risk of GS.15,16 Studies have also shown that leisure physical activity protects against GS or cholecystectomy, while a sedentary lifestyle increases risk for the condition.17–19 The mechanisms by which PA ameliorates GS pathogenesis are unclear. However, changes in lipid metabolism in the liver and in the peripheral organs may be involved,20–22 since decreased biliary cholesterol levels might prevent the formation of cholesterol supersaturated bile, and thus, the formation of GS.22 Even though the mechanism by which PA protects against the development of GS is not fully clear, it appears to involve both decreasing biliary cholesterol secretion and enhancing gallbladder and intestinal motility. PA may also positively affect the other factors related to the development of GS, such as high levels of triglycerides and serum insulin.19,20,22 Since GD is highly prevalent in the Mexican female population, determining the possible effect of recreational physical activity (RPA) on asymptomatic gallstones (AG) in adult Mexican women might facilitate a public health response.

Material and MethodsA cross-sectional analysis of women participating in the baseline assessment of the Health Workers Cohort Study (HWCS) was conducted. The study design, methodology and participants’ baseline characteristics have previously been published.23,24 Briefly, a total of 9,467 employees and employee relatives from three different Mexican health and academic institutions were invited to participate in this cohort study between March 2004 and April 2006. A total of 8,307 adults formally enrolled in the study following these invitations. With the aim of determining the association between RPA and risk of AG, from the initial pool of 6,292 female HWCS participants subjects with the following characteristics were excluded from the present analysis: participants diagnosed with cholecystectomy or symptomatic gallstones (n = 686), participants who did not undergo ultrasound examination of the gallbladder (n = 545), participants showing outlier energy intake values according to the standard deviation method (n = 89),25 and participants providing incomplete PA information (n = 19). The remaining 4,953 women were included in the present study.

Physical activity assessmentPhysical activity was assessed with a previously used PA questionnaire,26,27 which had been translated into Spanish and validated in an urban Mexican population.28 The questionnaire included a series of questions about the time (hours/week), frequency (days/week) and intensity (light, moderate, vigorous) of activities carried out during a typical week in the last year. The weekly time dedicated to 16 recreational PA items (including walking, running, cycling, aerobics, dancing, bowling, swimming, tennis, fronton, squash, softball/baseball, soccer, volleyball, football, and basketball) was calculated. The time spent performing these activities per week was then converted into metabolic equivalents (METs hours/ week) according to the criteria set forth in the compendium of physical activity by Ainsworth, et al.29,30 PA was merged and regrouped into the categories of minutes per day (< 10 min/day, ≥ 10 to < 30 min/ day, and ≥ 30 min/day); minutes per week (< 30 min/week, ≥ 30 to < 150 min/week, and ≥ 150 min/ week); and METs hours per week which were divided into tertiles for analysis. The highest category of minutes/day was 30 min or more of PA, which coincides with the minimum amount of exercise recommended by the Official PA guidelines.31–33

Asymptomatic gallstone disease assessmentParticipants’ history of GD was assessed with a self-administered questionnaire and an interview during the appointment for the baseline clinical evaluation. Participants who were found to have a history of symptomatic GS were excluded from the analyses. Participants were considered to have a symptomatic GD history if their clinical history was compatible with GD (right hypochondriac pain lasting more than 30 min, during the last five years), and there was either confirmatory ultrasonography or surgical confirmation of biliary disease. AG was defined as the presence of gallstones without history of right hypochondriac pain lasting more than 30 min, during the last five years, as revealed by vesicular lumen echoes that generated acoustic shadows in the ultrasonography; this standard has been used in previous studies.34–36 Ultrasound procedures were performed by experienced technicians using a realtime 3.5 MHz coupled transducer (SonoSite® 180PLUS™, Sonosite, Inc. Bothell, WA USA).

Assessment of other variablesInformation on a range of variables that have previously been identified as risk factors for GD37–39 was gathered. Self-administered questionnaires were used to obtain information about participants’ demographic characteristics (educational level, age, sex, income, marital status and occupation), use of hormone replacement therapy, use of oral contraceptives, parity, and use of cholesterol-lowering medications, thiazide diuretics, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication use. In addition to PA-related lifestyle factors, smoking status was assessed using the World Health Organization categorization (current, past and never).40 A semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire validated in a Mexican population41 was used to assess diet. Outlier values for energy intake were eliminated using the standard deviation method,25 and nutrient intake was energy-adjusted using the residual method42,43 and expressed as quintiles of consumption. Finally, participants were asked about weight changes experienced during the previous year, and this information was categorized as: no weight change, weight loss (≥ 5 kg), or weight gain (≥ 5 kg) in the past year. Participants who gained or lost less than 5 kg were categorized has experienced no weight change.

The ethics committees of the participating institutions approved the study protocol and all participants signed informed consent forms.

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics (medians, interquartile range) were calculated for all continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages were generated for the non-continuous variables. χ2 analyses were used to test for differences among groups in nominal categorical outcomes. AG prevalence, characteristics of AG cases and non-cases were assessed and are shown as the median and interquartile range (IR). Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). To estimate the magnitude of association between recreational PA and AG, we computed adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% CIs using multivariate logistic regression models, which were adjusted by age (≤ 39, 40-59 and ≥ 60 years), body mass index (BMI) [normal <25.0 (kg/m2); overweight ≥ 25.0 to < 30.0 (kg/m2); and obese ≥ 30.0 (kg/m2)], number of pregnancies (0, 1-2 and ≥ 3), diabetes mellitus (yes/no), medication use (yes/no), and energy-adjusted consumption of: dietary fiber (g/day), carbohydrates (quintiles of % energy), monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats (quintiles of % energy), alcohol (never, ≤ 2 and ≥ 3 drinks/week)44 and coffee. The Mantel-Haenszel extension chisquare test was used to assess the overall trend of OR across increasing category of physical activity (for example, tertiles of METs hours/week). A two-tailed P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using STATA 9.0 software (Stata statistical software 9.0, Stata Corporation Collage Station, TX, USA).

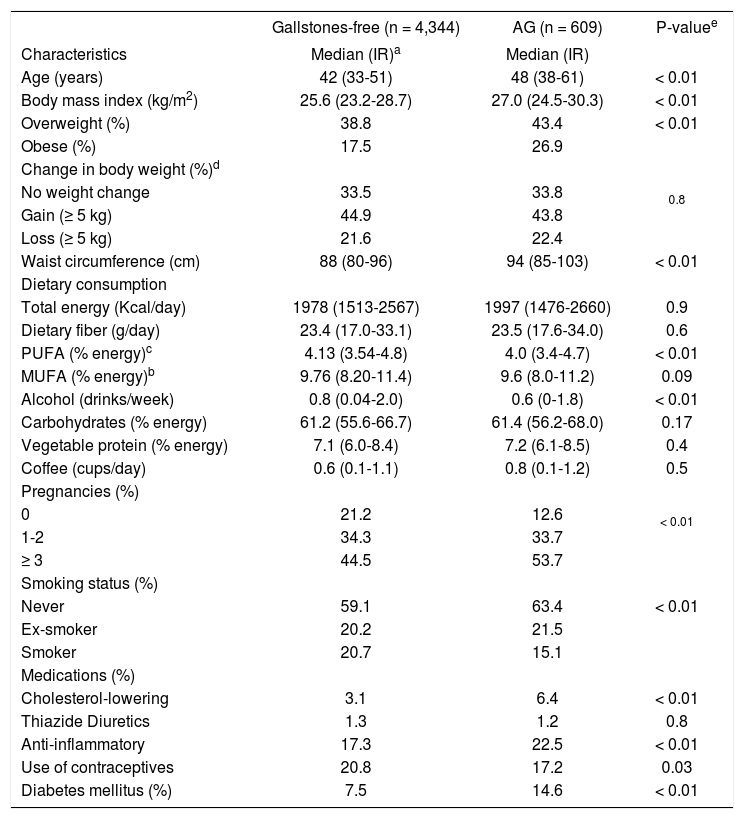

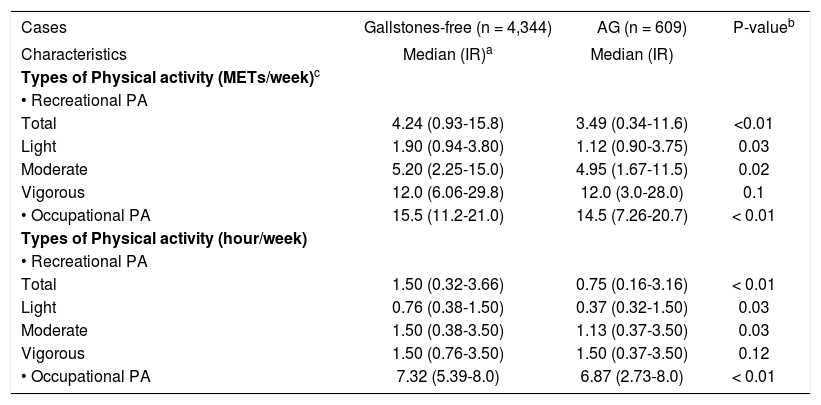

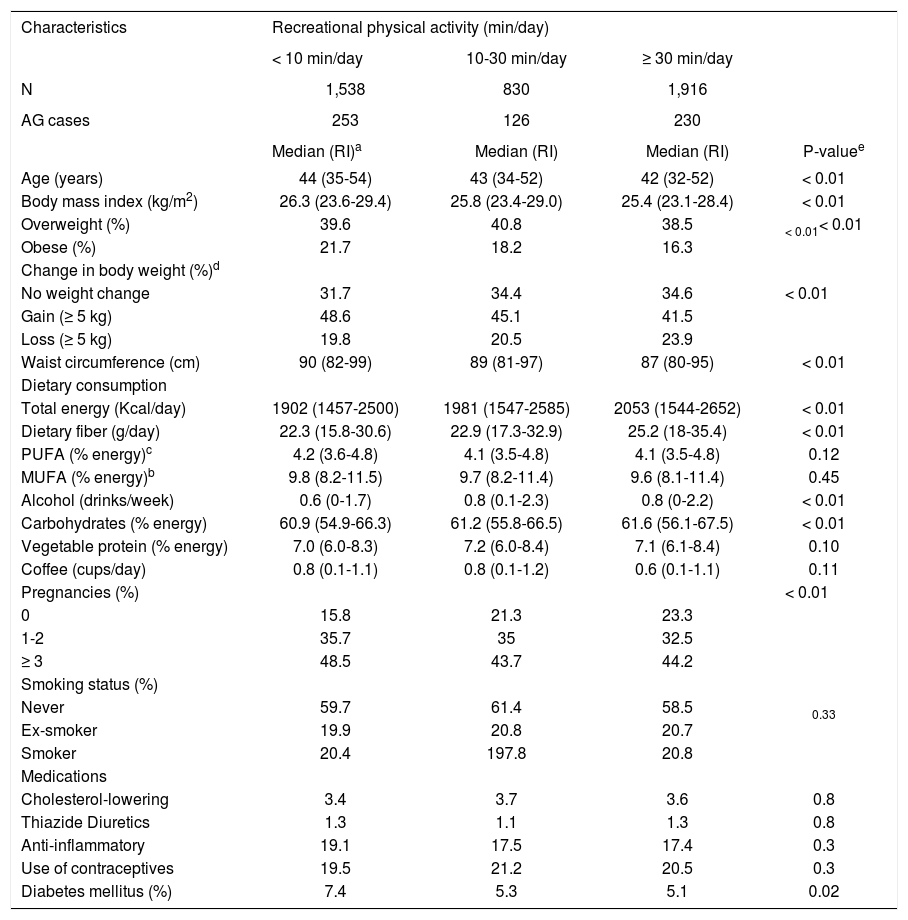

ResultsData collected from 4,953 women were analyzed, from which 609 (12.3%) participants with AG were detected. Overall, participants with AG were older than those without AG (48 vs. 42 years; P < 0.01), had a higher body mass index (BMI) [27.0 (kg/m2) vs. 25.6 (kg/m2); P < 0.01] and had a higher frequency of diabetes mellitus (14.6 vs. 7.5%; P < 0.01). Women who had ≥ 3 births showed a higher AG prevalence compared with those who had ≤ 2 births (53.7 vs. 44.5%, P < 0.01). Cigarette consumption was more frequent among participants with AG (40.9 vs. 36.6%, P < 0.01) (Table 1). Participants without AG engaged in more physical activity than participants with AG; this was true for total physical activity expressed in METs (4.2 vs. 3.5 METs hours/week; P < 0.01), light physical activity (1.9 vs. 1.12 METs hours/week; P = 0.03), moderate physical activity (5.20 vs. 4.95 METs hours/week; P = 0.02) and occupational physical activity (15.5 vs. 14.5 METs hours/week; P < 0.01) (Table 2). Women who engaged in greater recreational PA tended to be younger, have lower BMI and percentages of weight gain, and fewer pregnancies; these differences were statistically significant (Table 3).

Characteristics of the study population.

| Gallstones-free (n = 4,344) | AG (n = 609) | P-valuee | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Median (IR)a | Median (IR) | |

| Age (years) | 42 (33-51) | 48 (38-61) | < 0.01 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.6 (23.2-28.7) | 27.0 (24.5-30.3) | < 0.01 |

| Overweight (%) | 38.8 | 43.4 | < 0.01 |

| Obese (%) | 17.5 | 26.9 | |

| Change in body weight (%)d | |||

| No weight change | 33.5 | 33.8 | 0.8 |

| Gain (≥ 5 kg) | 44.9 | 43.8 | |

| Loss (≥ 5 kg) | 21.6 | 22.4 | |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 88 (80-96) | 94 (85-103) | < 0.01 |

| Dietary consumption | |||

| Total energy (Kcal/day) | 1978 (1513-2567) | 1997 (1476-2660) | 0.9 |

| Dietary fiber (g/day) | 23.4 (17.0-33.1) | 23.5 (17.6-34.0) | 0.6 |

| PUFA (% energy)c | 4.13 (3.54-4.8) | 4.0 (3.4-4.7) | < 0.01 |

| MUFA (% energy)b | 9.76 (8.20-11.4) | 9.6 (8.0-11.2) | 0.09 |

| Alcohol (drinks/week) | 0.8 (0.04-2.0) | 0.6 (0-1.8) | < 0.01 |

| Carbohydrates (% energy) | 61.2 (55.6-66.7) | 61.4 (56.2-68.0) | 0.17 |

| Vegetable protein (% energy) | 7.1 (6.0-8.4) | 7.2 (6.1-8.5) | 0.4 |

| Coffee (cups/day) | 0.6 (0.1-1.1) | 0.8 (0.1-1.2) | 0.5 |

| Pregnancies (%) | |||

| 0 | 21.2 | 12.6 | < 0.01 |

| 1-2 | 34.3 | 33.7 | |

| ≥ 3 | 44.5 | 53.7 | |

| Smoking status (%) | |||

| Never | 59.1 | 63.4 | < 0.01 |

| Ex-smoker | 20.2 | 21.5 | |

| Smoker | 20.7 | 15.1 | |

| Medications (%) | |||

| Cholesterol-lowering | 3.1 | 6.4 | < 0.01 |

| Thiazide Diuretics | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.8 |

| Anti-inflammatory | 17.3 | 22.5 | < 0.01 |

| Use of contraceptives | 20.8 | 17.2 | 0.03 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 7.5 | 14.6 | < 0.01 |

Physical activity characteristics of the study population.

| Cases | Gallstones-free (n = 4,344) | AG (n = 609) | P-valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Median (IR)a | Median (IR) | |

| Types of Physical activity (METs/week)c | |||

| • Recreational PA | |||

| Total | 4.24 (0.93-15.8) | 3.49 (0.34-11.6) | <0.01 |

| Light | 1.90 (0.94-3.80) | 1.12 (0.90-3.75) | 0.03 |

| Moderate | 5.20 (2.25-15.0) | 4.95 (1.67-11.5) | 0.02 |

| Vigorous | 12.0 (6.06-29.8) | 12.0 (3.0-28.0) | 0.1 |

| • Occupational PA | 15.5 (11.2-21.0) | 14.5 (7.26-20.7) | < 0.01 |

| Types of Physical activity (hour/week) | |||

| • Recreational PA | |||

| Total | 1.50 (0.32-3.66) | 0.75 (0.16-3.16) | < 0.01 |

| Light | 0.76 (0.38-1.50) | 0.37 (0.32-1.50) | 0.03 |

| Moderate | 1.50 (0.38-3.50) | 1.13 (0.37-3.50) | 0.03 |

| Vigorous | 1.50 (0.76-3.50) | 1.50 (0.37-3.50) | 0.12 |

| • Occupational PA | 7.32 (5.39-8.0) | 6.87 (2.73-8.0) | < 0.01 |

Characteristics of women by level of recreational physical activity.

| Characteristics | Recreational physical activity (min/day) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 10 min/day | 10-30 min/day | ≥ 30 min/day | ||

| N | 1,538 | 830 | 1,916 | |

| AG cases | 253 | 126 | 230 | |

| Median (RI)a | Median (RI) | Median (RI) | P-valuee | |

| Age (years) | 44 (35-54) | 43 (34-52) | 42 (32-52) | < 0.01 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.3 (23.6-29.4) | 25.8 (23.4-29.0) | 25.4 (23.1-28.4) | < 0.01 |

| Overweight (%) | 39.6 | 40.8 | 38.5 | < 0.01< 0.01 |

| Obese (%) | 21.7 | 18.2 | 16.3 | |

| Change in body weight (%)d | ||||

| No weight change | 31.7 | 34.4 | 34.6 | < 0.01 |

| Gain (≥ 5 kg) | 48.6 | 45.1 | 41.5 | |

| Loss (≥ 5 kg) | 19.8 | 20.5 | 23.9 | |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 90 (82-99) | 89 (81-97) | 87 (80-95) | < 0.01 |

| Dietary consumption | ||||

| Total energy (Kcal/day) | 1902 (1457-2500) | 1981 (1547-2585) | 2053 (1544-2652) | < 0.01 |

| Dietary fiber (g/day) | 22.3 (15.8-30.6) | 22.9 (17.3-32.9) | 25.2 (18-35.4) | < 0.01 |

| PUFA (% energy)c | 4.2 (3.6-4.8) | 4.1 (3.5-4.8) | 4.1 (3.5-4.8) | 0.12 |

| MUFA (% energy)b | 9.8 (8.2-11.5) | 9.7 (8.2-11.4) | 9.6 (8.1-11.4) | 0.45 |

| Alcohol (drinks/week) | 0.6 (0-1.7) | 0.8 (0.1-2.3) | 0.8 (0-2.2) | < 0.01 |

| Carbohydrates (% energy) | 60.9 (54.9-66.3) | 61.2 (55.8-66.5) | 61.6 (56.1-67.5) | < 0.01 |

| Vegetable protein (% energy) | 7.0 (6.0-8.3) | 7.2 (6.0-8.4) | 7.1 (6.1-8.4) | 0.10 |

| Coffee (cups/day) | 0.8 (0.1-1.1) | 0.8 (0.1-1.2) | 0.6 (0.1-1.1) | 0.11 |

| Pregnancies (%) | < 0.01 | |||

| 0 | 15.8 | 21.3 | 23.3 | |

| 1-2 | 35.7 | 35 | 32.5 | |

| ≥ 3 | 48.5 | 43.7 | 44.2 | |

| Smoking status (%) | ||||

| Never | 59.7 | 61.4 | 58.5 | 0.33 |

| Ex-smoker | 19.9 | 20.8 | 20.7 | |

| Smoker | 20.4 | 197.8 | 20.8 | |

| Medications | ||||

| Cholesterol-lowering | 3.4 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 0.8 |

| Thiazide Diuretics | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 0.8 |

| Anti-inflammatory | 19.1 | 17.5 | 17.4 | 0.3 |

| Use of contraceptives | 19.5 | 21.2 | 20.5 | 0.3 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 7.4 | 5.3 | 5.1 | 0.02 |

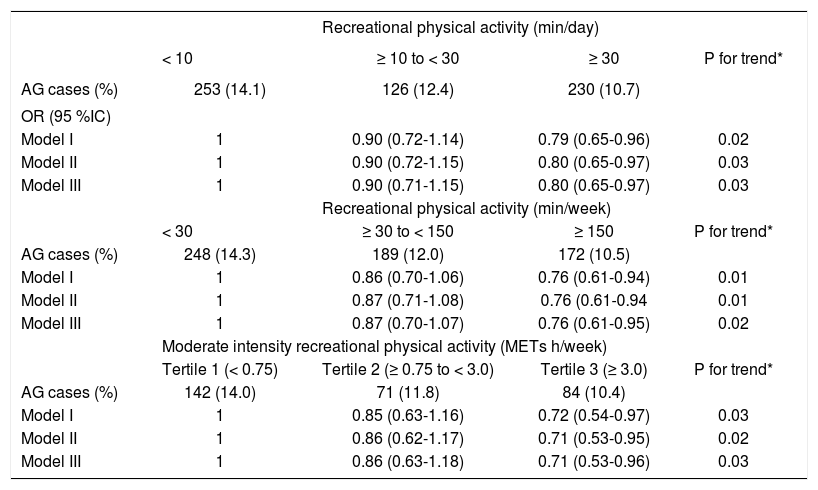

The multivariate analysis results showed an inverse association between recreational PA (min/day) and AG: comparing the intermediate level of physical activity (10-30 min/day) against the lowest level (< 10 min/day) an OR of 0.90 (95% CI: 0.72-1.14) was observed; then, comparing the highest level of physical activity (min/day) against the lowest level we found an OR of 0.79 (95% CI: 0.65-0.96); here, P for trend = 0.02, when the model was adjusted for age and BMI. Controlling for potential confounders slightly attenuated this association. However, even after adjustment for diabetes mellitus, tobacco use, use of medicines, total energy intake, intake of fiber, carbohydrates, polyunsaturated fat, monoun-saturated fat, alcohol and coffee, as well as weight change, the association remained significant; in this case, we found an OR of 0.90 (95% CI: 0.71-1.15) and 0.80 (95% CI: 0.65-0.97; P for trend = 0.03), when we compared intermediate vs. lowest and highest vs. lowest levels of recreational physical activity, respectively. This was true for recreational PA in hours per week OR = 0.86 (95% CI: 0.63-1.18) and 0.71 (95% CI: 0.53-0.96; P for trend = 0. 03) (Table 4).

Odds Ratio and 95% CI for relation between recreational physical activity and asymptomatic gallstones.

| Recreational physical activity (min/day) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 10 | ≥ 10 to < 30 | ≥ 30 | P for trend* | |

| AG cases (%) | 253 (14.1) | 126 (12.4) | 230 (10.7) | |

| OR (95 %IC) | ||||

| Model I | 1 | 0.90 (0.72-1.14) | 0.79 (0.65-0.96) | 0.02 |

| Model II | 1 | 0.90 (0.72-1.15) | 0.80 (0.65-0.97) | 0.03 |

| Model III | 1 | 0.90 (0.71-1.15) | 0.80 (0.65-0.97) | 0.03 |

| Recreational physical activity (min/week) | ||||

| < 30 | ≥ 30 to < 150 | ≥ 150 | P for trend* | |

| AG cases (%) | 248 (14.3) | 189 (12.0) | 172 (10.5) | |

| Model I | 1 | 0.86 (0.70-1.06) | 0.76 (0.61-0.94) | 0.01 |

| Model II | 1 | 0.87 (0.71-1.08) | 0.76 (0.61-0.94 | 0.01 |

| Model III | 1 | 0.87 (0.70-1.07) | 0.76 (0.61-0.95) | 0.02 |

| Moderate intensity recreational physical activity (METs h/week) | ||||

| Tertile 1 (< 0.75) | Tertile 2 (≥ 0.75 to < 3.0) | Tertile 3 (≥ 3.0) | P for trend* | |

| AG cases (%) | 142 (14.0) | 71 (11.8) | 84 (10.4) | |

| Model I | 1 | 0.85 (0.63-1.16) | 0.72 (0.54-0.97) | 0.03 |

| Model II | 1 | 0.86 (0.62-1.17) | 0.71 (0.53-0.95) | 0.02 |

| Model III | 1 | 0.86 (0.63-1.18) | 0.71 (0.53-0.96) | 0.03 |

Model I: age (≤ 39, 40-59, > 60 years), BMI (< 25.0, ≤ 25.0 to < 30.0, ≥ 30.0 kg/m2). Model II: further adjusted for energy intake (Kcal/day in quintiles), intake of energy-adjusted carbohydrates (% energy in quintiles), intake of energy-adjusted dietary fiber (g/day in quintiles), energy-adjusted polyunsaturated (% energy in quintiles) y monounsaturated (% energy in quintiles) alcohol consumption (never, ≤ 2 and ≥ 3 drinks/week), coffee consumption (0, 1, 2, 3, ≥ 4 cups/ day). Model III: additionally adjusted for parity (0,1-2, or ≥ 3 births), history of diabetes mellitus (yes or no), and weight change in the previous year (no weight change, weight loss, weight gain), smoking status (never, ex-smoker, smoker), thiazide diuretics (yes or no), anti-inflammatory drugs (yes or no), and oral contraceptive use (ever or never), use of hormone replacement therapy (yes or no). * The Mantel-Haenszel extension χ2 test was used to assess the overall trend of OR across increasing category of physical activity.

These findings support the hypothesis that recreational PA (> 30 min/day) is a protective factor against AG development. In keeping with prior reports, we found that PA duration affects the level of protection it provides against GD. Since researchers have identified 150 min per week of moderate to vigorous physical activity as necessary to reduce the risk of chronic illness, we used this value as a cutoff point for sufficient protective physical activity.33,45 In this study, the amount of physical activity in the highest category is equivalent to exercising for 30 min per day for 5 days per week, or 2.5 h per week. Leitzmann, et al. ’ findings of an inverse association between recreational PA and the risk of cholecystectomy in adult women, regardless of other co-variables, led them to propose that 2 to 3 h of recreational exercise per week could reduce GD risk by up to 20%. Leitzmann’s group also assessed this pattern in a cohort of men and proposed that 34% of symptomatic GD cases might have been prevented by 30 min of moderate PA 5 times per week.17,19

The mechanisms by which PA protects against GD are not clear. They could be related to the prevention of insulin resistance,21 since PA improves cells’ glucose utilization. However, a positive relationship has been found between insulin levels and GD,46,47 in which the mechanisms involved, could be responsible for the increases in cholesterol low density lipoprotein receptors in the liver.48,49 PA may also be protective by reducing bile cholesterol saturation and increasing HDL-cholesterol,50–52 increasing mucin production in the gallbladder wall and/or mitigating gallbladder contraction and emptying pathologies. Moreover, further studies have reported an inverse association between triglyceride levels and physical activity. Therefore, decreases in triglyceride levels related to physical activity promote diminished mucin production and thus lower the risk of gallstones.18 Finally, it has also been observed that prolonged intestinal transit time is a risk factor for GD. This may be due to increased deoxycholic acid formation in, and absorption from, the large bowel. Thus, when the intestinal transit time is prolonged, the proportion of deoxycholic acid in bile is increased.53 Physical activity has a positive effect on this process of GD development because it stimulates intestinal motility.54 The relationship between physical activity and gallstones has been previously evaluated, and researchers found that there is a greater risk of developing GD when BMI is greater than 30.8 Diet also plays a role, since along with PA; nutritional factors like monounsaturated fat and dietary fiber intake diminish GD risk.

One of the present study’s limitations was that its cross-sectional design made it difficult to examine the potential causal relationship of recreational PA with AG. Another important limitation was that we did not find a dose-response relationship between recreational PA and AG, one explanation could be the greater probability of misclassification of physical activity in these categories, may be due to the possibility of measurement error in our assessment of PA. Furthermore, the study population cannot be considered representative of the Mexican population as a whole, although it is representative of middle to low income women residing in urban, central Mexico. However, our findings can be applied to women with similar characteristics to those in the present study, since participants were in an age group susceptible to gallstones and the type of disease presentation is representative of that seen clinically, predominantly biliary colic. The study design also has significant strengths. In order to reduce bias, we did not include information about lifestyle changes in the diagnosis of symptomatic GD or cholecystectomy. We also implemented diagnostic measures to mitigate the temporality problems posed by the cross-sectional design. Unlike previously published research, we only included cases of AG in our analysis.

ConclusionsThe results of this study evaluating the association between recreational PA and AG in Mexican women confirmed the inverse association between PA and AG, and support the promotion of moderate physical activity for the prevention of chronic disease, including gallstones. The apparent protective effect can be achieved not only by the duration of physical activity but also its intensity. Future longitudinal studies are needed to establish the causal relationship between PA and GD.

Abbreviations- •

95% CIs: 95% confidence intervals.

- •

AG: asymptomatic gallstones.

- •

BMI: body mass index.

- •

DM2: diabetes mellitus type 2.

- •

GD: gallstone disease.

- •

GS: gallstones.

- •

HWCS: Health Workers Cohort Study.

- •

IR: interquartile range.

- •

MET: metabolic equivalents.

- •

OR: odds ratios.

- •

PA: physical activity.

- •

RPA: recreational physical activity.

Supported by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (grant no. 87783), and the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (grant no. 2005-785-012).