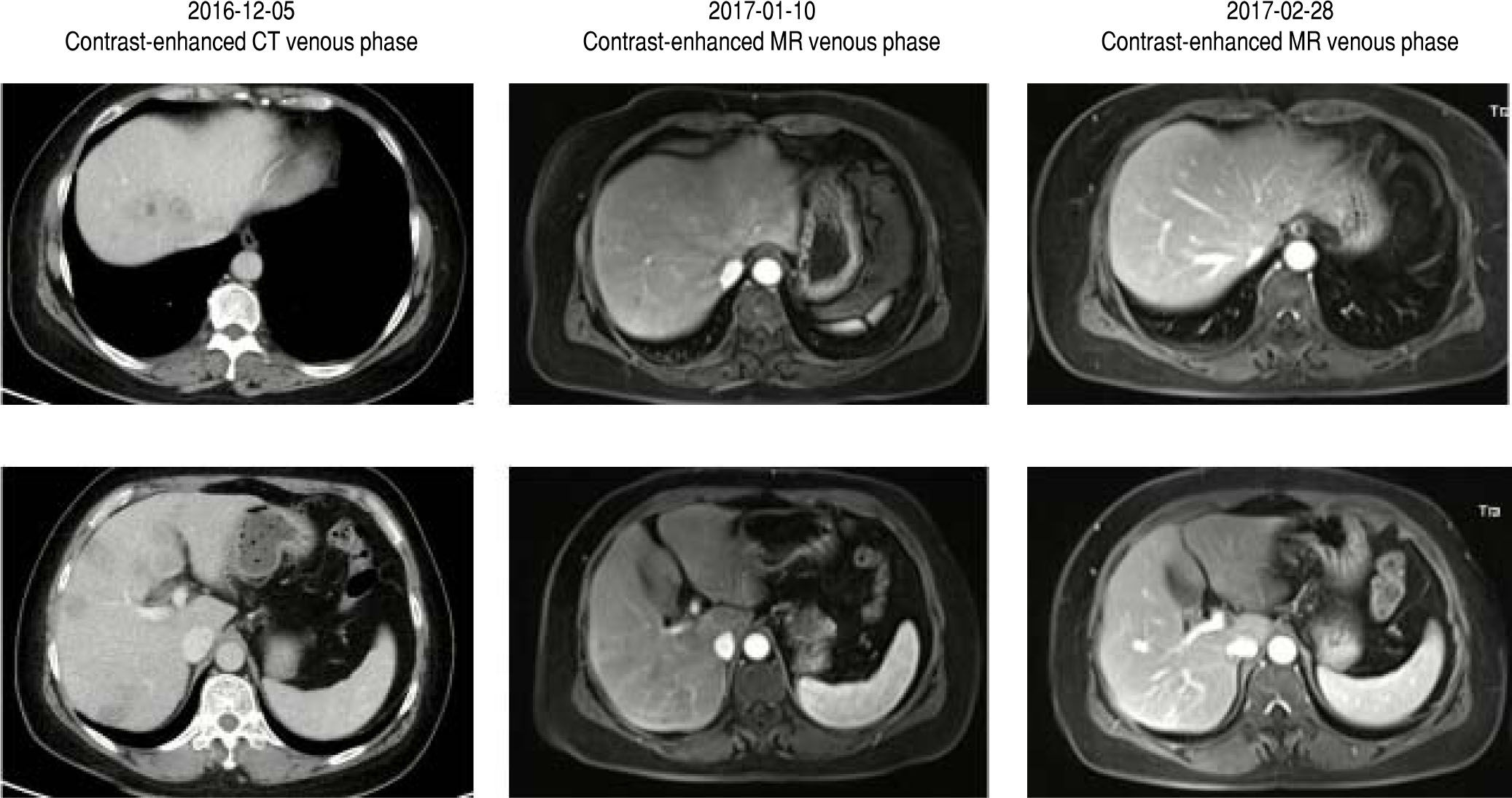

A previously healthy 59-year-old female presented with intermittent fever for 4 days. The highest temperature was 40 °C. Buluofen was given at home, but fever relapsed. She denied any history of liver diseases. She did not smoke or have any history of alcohol or drug abuse. On physical examinations, there were no positive signs. At our admission, abnormal laboratory tests (2016-12-19) were primarily shown as follows: white blood cell was 12.3 x 109/L (reference range: 3.5-9.5 x 109/L), percentage of neu-trophil was 81.9% (reference range: 40-75%), C reactive protein was 99.4 mg/L (reference range: 0-8 mg/L), procal-citonin was 0.378 ng/mL (reference range: 0-0.05 ng/mL), total bilirubin was 48.88 umol/L (reference range: 5.1-22.2 umol/L), direct bilirubin was 17.2 umol/L (reference range: 0-8.6 umol/L), aspartate aminotransferase was 111.68 U/L (reference range: 13-35 U/L), alanine ami-notransferase was 181.88 (reference range: 7-40 U/L), alkaline phosphatase was 154.83 U/L (reference range: 35-135 U/L), gamma-glutamyl transferase was 164.91 U/L (reference range: 7-45 U/L), albumin was 38.2 g/L (reference range: 40-55 g/L), mycoplasma pneumoniae antibody IgM was weakly positive, and anti-influenza virus antibody IgM was weakly positive. Viral hepatitis A, B, C, and E were excluded. Alfa-fetal protein, carcinoembryonic antigen, CA50, CA125, CA153, CA199, and CA242 levels were within the normal range. HIV was negative. Creatinine and prothrombin time were within the normal range. Antinu-clear antibody, anti mitochondrial antibody, anti mito-chondrial antibody type M2, and anti smooth muscle antibody were negative. IgG4 test was not available. Intravenous infusion of antibiotics and hepato-protective drugs was given. Six days after treatment, the symptoms gradually disappeared. Thus, blood culture was not performed. Laboratory tests (2016-12-25) were primarily shown as follows: white blood cell was 9.5 x 109/L, percentage of neu-trophil was 68.1%, total bilirubin was 11.4 umol/L, direct bilirubin was 5.3 umol/L, aspartate aminotransferase was 13.3 U/L, alanine aminotransferase was 51.01 U/L, alkaline phosphatase was 217.21 U/L, and gamma-glutamyl trans-ferase was 175.26 U/L. Notably, computed tomography (CT) scans showed multiple low density lesions on the liver, some of them exhibiting a “bulls eye” sign (Figure 1). Hepatic metastatic malignancy was suspected. A positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) scan was further performed, which showed that the lesions were highly metabolic. Hepatic epithelioid heman-gioendothelioma was suspected. Finally, a targeted liver biopsy under ultrasound guidance was performed, which excluded malignancy. Because the diagnosis was unclear, no active anti-tumor treatment or surgery was planned. Follow-up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) surprisingly revealed no hepatic masses (Figure 1). About one month later, another MRI was performed, which confirmed a normal liver again (Figure 1). Based on the history, clinical presentations, and imaging findings, a diagnosis of hepatic inflammatory pseuduotumor was considered. Now, she is keeping well without any other complaints. Laboratory tests (2017-2-25) were primarily shown as follows: white blood cell was 5.5 x 109/L, percentage of neu-trophil was 43.4%, total bilirubin was 10.5 umol/L, direct bilirubin was 3.3 umol/L, aspartate aminotransferase was 32.57 U/L, alanine aminotransferase was 38.54 U/L, alkaline phosphatase was 95.96 U/L, and gamma-glutamyl transferase was 51.39 U/L.

DiscussionHepatic inflammatory pseuduotumor is a rare disease, including inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, inflammatory fibrosarcoma, and plasma cell granuloma. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver was firstly described by Pack,1 which was characterized by dominant spindle cell proliferation with varying inflammatory components.2,3 The etiology of hepatic inflammatory pseuduotumor remains unclear.3,4 It may be caused by infection, autoimmune conditions, trauma, and surgical inflammation.5,6 Abdominal pain is the most common symptom.7 Other symptoms include fever and malaise. Some cases are asymptomatic. Hepatic inflammatory pseuduotumor is more frequently seen in Asia and is more common in men.3 Imaging findings are often non-specific and are sometime misinterpreted as malignancy. Liver biopsy can be helpful in clinching the diagnosis. Surgery may be preferable, especially in patients with low surgical risk.3 Only a small proportion of patients suffer from the recurrence or metastasis after partial hepatectomy.8,9 Observation or conservative therapy is an alternative.

In conclusion, we report a female patient with multiple hepatic inflammatory pseuduotumors which resolved spontaneously. Because definitive diagnostic criteria remain unavailable, our case underwent CT, PET-CT, MRI, and liver biopsy to exclude malignancy. A close follow-up observation remains crucial. Lastly, a wait-and-see strategy may be appropriate if a hepatic inflammatory pseudotu-mor liver is diagnosed.

Conflict of InterestNone.

FundingNone.

Author ContributionsXingshun Qi, Yue Hou, Sha Chang, Xiaozhong Guo: treated, cared, and followed the case.

Xingshun Qi, Lei Han, Ankur Arora: discussed the case and interpreted the images.

Xingshun Qi, Ran Wang: reviewed the literature and drafted the manuscript.

All authors have made an intellectual contribution to the manuscript and approved the submission.