There is little information on survival rates of patients with primary biliary cholangtis (PBC) in developing countries. This is particularly true in Latin America, where the number of liver transplants performed remains extremely low for patients with advanced liver disease who fulfill criteria for liver transplantation. The goal of this study was to compare survival rate of patients with PBC in developing countries who were treated with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) versus survival of patients who received other treatments (OT) without UDCA, prescribed before the UDCA era.

Material and MethodsA retrospective study was performed, including records of 78 patients with PBC in the liver unit in a third level referral hospital in Mexico City. Patients were followed for five years from initial diagnosis until death related to liver disease or to the end of the study. Patients received UDCA (15 mg/kg/per day) (n = 41) or OT (n = 37) before introduction of UDCA in Mexico.

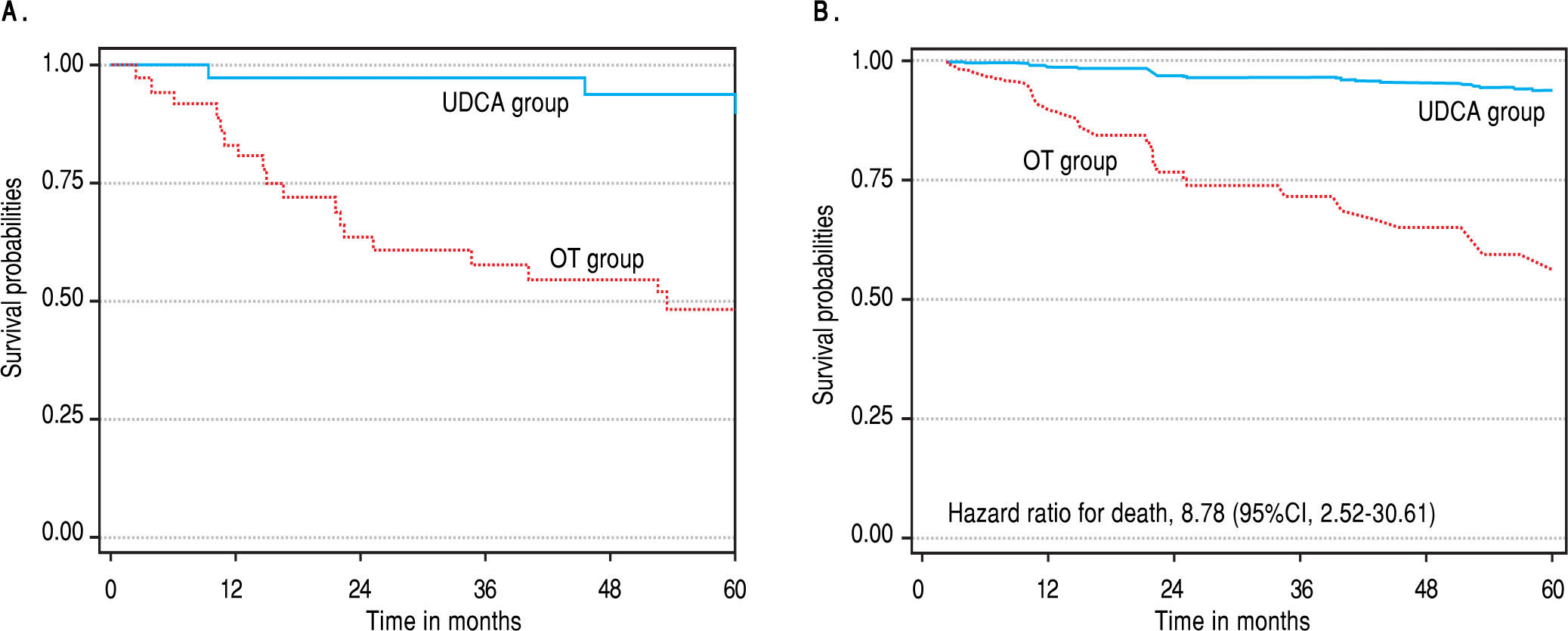

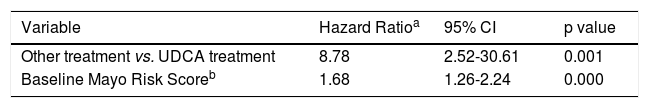

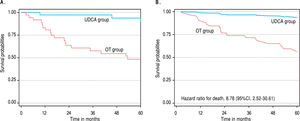

ResultsResponse to treatment was higher in the group that received UDCA. In the five years of follow-up, survival rates were significantly higher in the UDCA group than in the OT group. The hazard ratio of death was higher in the OT group vs. UDCA group, HR 8.78 (95% CI, 2.52-30.61); Mayo Risk Score and gender were independently associated with the risk of death.

ConclusionsThe study confirms that the use of UDCA in countries with a limited liver transplant program increases survival in comparison to other treatments used before the introduction of UDCA.

Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) is an autoimmune liver disease characterized by progressive destruction of intrahepatic bile ducts, which may lead to biliary cirrhosis, portal inflammation, and liver failure.1,2 Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is the only drug approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat PBC, with a recommended dosage of 13-15 mg/kg/day.1-3 The use of obeti-cholic acid is on the horizon.4

It has been suggested that UDCA treatment improved the serum liver test results, slowed the histological progress, and improved patients’ survival without an orthotropic liver transplant.5,6 However, the effect of UDCA on survival is still controversial.7,8

At present, studies on PBC have mostly been carried out in Asia, Europe, Australia, and North America, in developed countries with liver transplant programs for PBC.2,5-8 However, there is little information about PBC in Latin America. Currently, there are no studies in Mexico or other countries in Latin America that evaluate the medium-term effect of UDCA treatment on survival of patients with PBC.

The aim of this study was to compare survival rates of patients in developing countries with PBC using UDCA versus survival rates of patients who received other drugs (OT) prescribed before the UDCA era.

Material and MethodsPatientsA retrospective study was performed in the Department of Pathology of the National Institute of Medical Sciences and Nutrition Salvador Zubiran in Mexico City, included patients diagnosed with PBC between 1971 and 2011. All patients who were included had histological and biochemical evidence of cholestasis based mainly on nonsuppurative destructive cholangitis and destruction of interlobular bile ducts, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) elevation at least 1.5 times the upper limit normal (ULN), and presence of positive antimitochondrial antibody (AMA). Exclusion criteria were features suggestive of other coexistent liver diseases, including overlap syndrome, alcoholic liver disease, a positive serological test for hepatitis B or C, non-alcoholic stea-tohepatitis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. The histological stage was assessed using Ludwig criteria: portal hepatitis, bile duct abnormalities, or both are present (stage 1), Peri-portal fibrosis is present, with or without periportal inflammation (stage 2), bridging fibrosis or necrosis or both (stage 3), and cirrhosis (stage 4).9

The following parameters were obtained from medical records: age, gender, associated diseases, symptoms, and liver function test [serum bilirubin levels, albumin, pro-thrombin time, alkaline phospatase (ALP), alanine ami-notransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST)]. Results of liver function tests were recorded at baseline, one month and one year after starting the treatment. The cut-off points used were: ALP 120 U/L as the upper limit of normal (ULN), 35 U/L for AST and ALT, and 1.0 mg/ dL for bilirubin. The lower limit of normal (LLN) for albumin was 3.5 g/dL.10 Patients had received UDCA (15 mg/kg/per day) since 1992 and before other drugs (OT) as colchicine (n = 28), cholestyramine (n = 18), penicilla-mine (n = 7), azathioprine (n = 5), or prednisolone (n = 13), at standard doses. In some cases, patients received more than one drug.

Ethical aspectsThis study was approved by the Ethics Board of the National Institute of Medical Sciences and Nutrition Salvador Zubiran, Mexico City, Mexico. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the institution's human research committee.

Statistical analysesIn descriptive analyses, data are expressed as means ± standard deviation, and percentages. Categorical variables were compared by %2 test among both groups and continuous variables by Student t-test. A paired t test was used to compare means before and after one month of treatment. The biochemical response to UDCA or OT was evaluated by comparing proportion of treatment response at one month and at one year after treatment, according to Barcelona criteria (decrease in ALP > 40% of the baseline level or normal level), Paris criteria (ALP level < 3 ULN, together with AST level < 2 ULN and a normal bilirubin level), Rotterdam criteria (normal bilirubin and albumin concentrations when one or both parameters were abnormal before treatment, or normal bilirubin or albumin concentrations after treatment when both were abnormal at entry), and Toronto criteria (ALP level < 1.76 ULN).2,11

Survival analysis was used: The follow-up started from the date at histological diagnosis of PBC, time zero (t0), and the end point was liver-related death. Time at event was calculated. Patients who did not present the event was censored at the end of the study, also was censored patients who died from causes unrelated to liver failure and patients that were lost at follow-up; also were censored patients referred for liver transplantation at the moment of OLT. Liver-related death was defined as death due to liver failure or death occurring within two months of an episode of variceal bleeding, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatorenal syndrome, or hepatic encephalopathy.12

Probabilities of survival were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. For the univariate analyses, we compared the survival functions of categorical variables using the log-rank test. To compare survival by continuous variables, Cox proportional hazard regression model with one only variable was used.

Multivariate analysis to evaluate the associations between treatments received and the survival function of patients with CBP was done using Cox proportional-hazard risk regression models. Variables with p value less than 0.20 at univariate analysis were included in the multivaria-ble analyses; and in the final model, variables statistically associated with the risk of death or important confounder variables were included.13 Model assumptions and good fit were tested. The analysis was performed using the statistical software STATA (version 12.0, STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

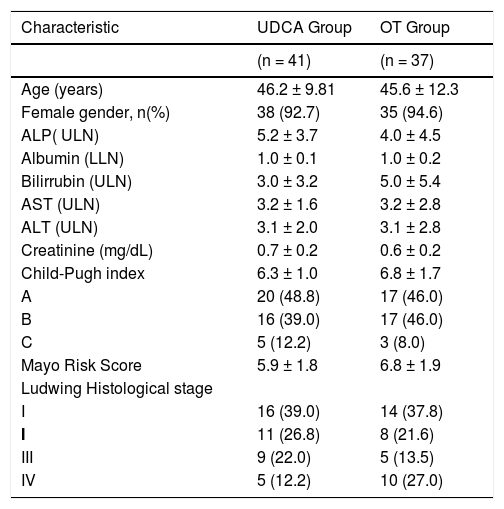

ResultsBaseline characteristicsA total of 78 patients matched by age and sex were included: 41 in the UDCA Group and 37 in the OT Group. When comparing the baseline characteristics of the treatment groups (Table 1), a higher concentration of bilirubin and higher Mayo Risk Score were found in the OT group and respect liver damage, in UDCA group fibrosis (n = 20/41) and cirrhosis (n = 5/41) ; and in OT group fibrosis (n = 13/38) and cirrhosis (n = 10/38) was found.

Baseline characteristics of the patients in this study.

| Characteristic | UDCA Group | OT Group |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 41) | (n = 37) | |

| Age (years) | 46.2 ± 9.81 | 45.6 ± 12.3 |

| Female gender, n(%) | 38 (92.7) | 35 (94.6) |

| ALP( ULN) | 5.2 ± 3.7 | 4.0 ± 4.5 |

| Albumin (LLN) | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.2 |

| Bilirrubin (ULN) | 3.0 ± 3.2 | 5.0 ± 5.4 |

| AST (ULN) | 3.2 ± 1.6 | 3.2 ± 2.8 |

| ALT (ULN) | 3.1 ± 2.0 | 3.1 ± 2.8 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

| Child-Pugh index | 6.3 ± 1.0 | 6.8 ± 1.7 |

| A | 20 (48.8) | 17 (46.0) |

| B | 16 (39.0) | 17 (46.0) |

| C | 5 (12.2) | 3 (8.0) |

| Mayo Risk Score | 5.9 ± 1.8 | 6.8 ± 1.9 |

| Ludwing Histological stage | ||

| I | 16 (39.0) | 14 (37.8) |

| I | 11 (26.8) | 8 (21.6) |

| III | 9 (22.0) | 5 (13.5) |

| IV | 5 (12.2) | 10 (27.0) |

Data are expressed as means ± standard deviation. ALP: alkaline phosphate. ULN: Upper limit of normal. AST: aspartate aminotransferase. ALT: alanine aminotransferase. LLN: lower limit of normal. UDCA: ursodeoxy-cholic acid and other drugs. OT: other drugs.

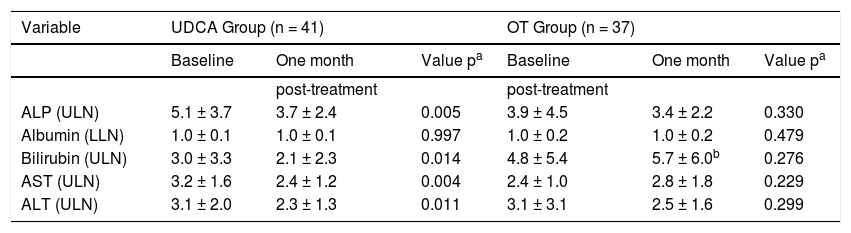

After one month of treatment, an intragroup comparison of UDCA group showed a significant reduction in ALP, total bilirubin, AST, and ALT concentration; no difference with statistical significance was observed in the OT group (Table 2). Furthermore, when comparisons after one month post-treatment between groups were done, total bilirubin (ULN) was statistically different; it was higher in the OT group (2.1 ± 2.3 vs. 5.7 ± 6.0, p = 0.007).

Biochemical indicators of hepatic function before and after one month of treatment.

| Variable | UDCA Group (n = 41) | OT Group (n = 37) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | One month | Value pa | Baseline | One month | Value pa | |

| post-treatment | post-treatment | |||||

| ALP (ULN) | 5.1 ± 3.7 | 3.7 ± 2.4 | 0.005 | 3.9 ± 4.5 | 3.4 ± 2.2 | 0.330 |

| Albumin (LLN) | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.997 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.479 |

| Bilirubin (ULN) | 3.0 ± 3.3 | 2.1 ± 2.3 | 0.014 | 4.8 ± 5.4 | 5.7 ± 6.0b | 0.276 |

| AST (ULN) | 3.2 ± 1.6 | 2.4 ± 1.2 | 0.004 | 2.4 ± 1.0 | 2.8 ± 1.8 | 0.229 |

| ALT (ULN) | 3.1 ± 2.0 | 2.3 ± 1.3 | 0.011 | 3.1 ± 3.1 | 2.5 ± 1.6 | 0.299 |

Data are expressed as means ± standard deviation. ALP: alkaline phosphate Upper limit of normal (ULN) = 120 U/L, albumin lower limit of normal (LLN) = 3.5 g/dL, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (ULN = 35 U/L), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (ULN = 35 U/L), bilirubin (ULN = 1.0 mg/dL). a Paired t test. b Student t test, p < 0.05.

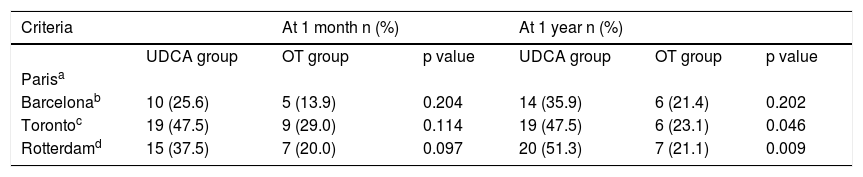

Table 3 shows the treatment response at one month and at one year post-treatment in light of the different criteria commonly used to evaluate treatment response in CBP patients. For all criteria, a higher percentage of response was observed in the UDCA group compared to the OT group. Nevertheless, this difference was statistically significant only after one year of the treatment, according to Toronto and Rotterdam criteria.

Treatment response according to different criteria.

During the follow-up period, 21 patients died from liver-related disease. In the UDCA group, three patients died, while in the OT group 18 died. The survival probability at one year was 0.97 (95% CI, 0.83-0.99) in the UDCA group and 0.83 (95% CI, 0.67-0.92) in the OT group; and the survival probabilities at 5 years were 0.89 (95% CI, 0.70-0.96) in the UDCA group and 0.49 (95% CI, (0.31-0.64) in the OT group, p < 0.001 (Figure 1A).

A. Survival probabilities estimates by Kaplan-Meier method, in five years of follow-up of CBP patients treated with UDCA and others drugs vs. OT without UDCA. B. Adjusted survival curves obtained from a Cox Proportional Hazard Model by treatment (OT vs. UDCA) and letting Mayo Score Risk be the mean value (6.3) and female gender.

In univariate analysis, gender, total bilirubin (ULN), alanine aminotransferase (ULN), score Child-Pugh, his-tologic stage (IV vs. I to III), and Mayo Risk Score were factors related to risk of death (p < 0.20). In multivariate analyses, treatment, gender, and Mayo Risk Score were associated with risk of death; the HR of the group in the OT treatment vs. patients in the UDCA group was 8.78 (95% CI, 2.52-30.61), p = 0.001; patients that received OT died at a rate 8.78 times higher than those patients that received treatment with UDCA, where the Mayo Risk Score and the gender are held constants. In the same way, for each increase of one point in the Mayo Risk Score, the rate of death for liver disease was higher by 68% after adjustment by treatment group and by gender (Table 4, Figure 1B). Figure 1B shows the difference in survival probabilities to females with 6.3 points in Mayor Risk Score treated with UDCA or OT.

DiscussionResults suggest UDCA treatment as an optimum choice for patients with PBC not suitable for a liver transplant and considering the higher survival probability after five years with UDCA compared to those in the OT group (0.89 vs. 0.49).

Results of this study confirm UDCA as proper treatment for patients with PBC in countries where liver transplants are still limited. Treatment response at one month and at one year of treatment was better in patients treated with UDCA.

In Mexico, patients with histological diagnosis of PBC between 1972 and 1992 showed low probability of survival, 0.75, 0.44, and 0.13 at 1, 5, and 7 years.14 These probabilities are lower than those reported in other countries.5,11,12,15-17

But survival probabilities at 5 years, 0.89, found in the present study in patients admitted at a third level referral hospital in Mexico City between 1992 and 2011 and treated with UDCA are similar to survival probabilities reported at 5 years by Zhang, et al., 0.86,2, ter Borg, et al., 0.8718 and Kuiper, et al., 0.90,12 in patients treated with UDCA. Differences in the grade of liver damage, treatment received, and number of patients included could explain differences in survival probabilities. In the studies of the Mexican population, patients treated before 1992 were treated with drugs other than UDCA.

Treatment with 10-15 mg/kg/day UDCA vs. a placebo has been evaluated in various clinical essays,19-25 but not all studies report UDCA as beneficial for treating PBC.7,8 In the present study, results show a survival difference between the UDCA and OT group.

Different prognostic factors with an impact on survival of PBC patients have been described: degree of hepatic damage at time of diagnostic; serum bilirubin higher than 1.57 mg/dL; serum albumin concentration lower than 3.8 mg/dL; and lack of response to UDCA treatment.15,16,26 In present study, UDCA treatment, gender, and Mayo Risk Score had impacts on the mortality of PBC patients. These findings are consistent with other reports.2,15,16

Before the UDCA era, the main reason for hepatic transplants in the United States was PBC. In the last few decades, the number of patients with PBC who require hepatic transplants has diminished by 20%.27 According to U.S. statistics, PBC patients are now the sixth choice for suggested hepatic transplants.28

The use of UDCA therapy to slow histological progression has a greater impact in Latin America because hepatic transplant program development there is very heterogeneous. Presently, hepatic transplants are only performed in 13 of the 19 countries of Latin America.29,30

In some countries, like Mexico, the programs are still being developed and it is exceptional to find a hepatic transplant program more than 10 years old that fulfills all necessary quality criteria. Therefore, it is hard to compare Latin American statistics to European or North American programs. It is necessary to continue to do research that will allow us to better typify PBC patients in Latin American countries and their response to UDCA treatment and to continue to assess the need, benefits, and risks of subjecting PBC patients to liver transplants.

Limitations of our study are related to patient data collected retrospectively; however, selection and recall biases were minimized because information about diagnoses and drug treatment was taken from clinical records.

The study suggests that the use of UDCA improves survival in patients with PBC in Mexico. Further randomized controlled studies should be conducted to evaluate the effect of UDCA therapy on the natural history, clinical manifestation, and prognosis of patients with PBC in Latin America.

Abbreviations- •

95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

- •

ALP: alkaline phosphatase.

- •

ALT: alanine aminotransferase.

- •

AMA: antimitochondrial antibody.

- •

AST: Aspartate aminotransferase.

- •

HR: hazard ratio.

- •

LLN: lower limit of normal.

- •

OLT: orthotopic liver transplantation.

- •

OT: other treatments.

- •

PBC: primary biliary cirrosis.

- •

UDCA: ursodeoxycholic acid.

- •

ULN: upper limit normal.

The authors have no competing interests.