Introduction

Family support is the main predictor of whether older persons remain in the community and whether admission to a permanent care facility or other center is delayed or avoided. Studies of patients with dementia have shown that caregiver characteristics (relation to the patient, age, employment status, persons in the household, symptoms of anxiety or depression, and quality of life) are much more accurate predictors of severity or symptoms of dementia.1,2

Many studies have documented the negative repercussions of caregiving on health. Although all such studies note that the most important consequences are psychological (particularly, an increased frequency of anxiety and depression3-5), other effects are the substantial repercussions on physical health,6 a considerable increase in social isolation,3,7 and a worsening economic status.7 In addition, caregivers do not appear to seek medical help often, and most of their problems go undiagnosed.4

Attempts to measure the impact of caregiving have used nonspecific instruments that analyze quality of life or the presence of psychopathological symptoms such as anxiety or depression. Attempts to create instruments to measure the impact of caregiving more directly have led to the use of the term "burden." The burden of care depends on the repercussions of caregiving, the coping strategies used, and the support available. A number of scales have been developed to measure this burden objectively. Among them, the best known are the Screen for Caregiver Burden8 and the Caregiver Burden Interview.9 Their usefulness lies in their ability to identify persons at greater risk or with greater needs, and to serve as a predictor of institutionalization. Although quality of life and burden of care are clearly related, burden of care is a better predictor of institutionalization.10

Many types of intervention have been described for caregivers of patients with dementia, with the aim of improving patient care and the caregiver's self-care.11 Some studies have shown these interventions to be effective.12-15 Measurements of effectiveness in these studies were based on the delay in institutionalization,13 decreased prevalence of anxiety or depression in caregivers14,15 and reduced burden of care.15 However, a recent meta-analysis,16 while noting the beneficial effects of psychosocial interventions, failed to find specific benefits in terms of burden of care. Another review of these interventions concluded that no recommendations could be established in view of the lack of adequate studies.17

The ALOIS program is an educational program aimed at principal caregivers of patients with dementia. The intervention is based on group health education led by primary care professionals at health centers. The program intends to provide caregivers with knowledge about dementia, and to give them an opportunity to exchange ideas among themselves, and to learn different skills for caregiving and self-care.

Our aim in the present study was to evaluate the profile and burden of care in caregivers who participated in the ALOIS program. We also attempted to evaluate the usefulness of the program from a subjective (caregivers´ perceived usefulness) and an objective point of view (possible influence on burden of care).

Material and Methods

The program was begun in 1998 in a Health Area in the Community of Madrid (central Spain). A total of 24 primary care professionals were invited to take part. A 20-hour workshop was held to train the trainers, and six teams were then created. Each team consisted of at least one physician, a nurse and a social worker.

The educational program took place in 8 weekly sessions of 2 hours each. The key points to be communicated in each session were selected in advance to ensure similarity across sessions led by different teams.

Caregivers were recruited by members of the ALOIS program teams and by other staff members at participating primary care centers, who were informed about the program and asked to recruit caregivers from their own patient list. Caregivers of patients with any type of dementia were allowed to participate. In general, only the main care provider for any given patient took part.

The instruments we used to evaluate the results of the program were caretaker´s profile, Zarit´s Caregiver Burden Interview, and a specially-designed questionnaire developed for participants to evaluate the program.

Results

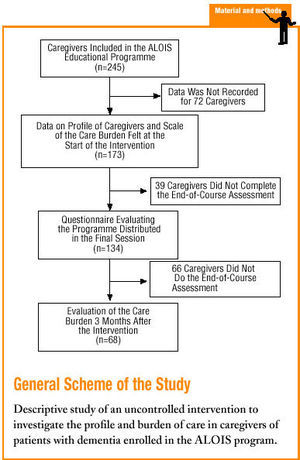

Between 1998 and 2000 we included in the program 227 principal caregivers, distributed in 16 groups of 8 to 20 participants each. Data were available for 12 groups (in 3 groups no evaluation tests were used, and in 1 group the results were lost).

Data for the caretaker profile and Caretaker Burden Interview were obtained at the start of the program for 173 caregivers. The most common characteristics were female sex (83.9%), mean age 54.6 years (range, 26-83 years), married (82.5%), no formal education or primary school education only (70.2%), housewife (54.3%), and patient's daughter (58.5%). Table 1 shows the distribution of the participants according to educational level, employment status, and relation to the patient. About one-fourth (24%) of the caregivers did not live in the same household as the patient, although they were considered the main care provider. The informal help received with care (mostly from other relatives of the patient) was considered substantial by 60.3% of the caregivers, and 4.7% received formal help from a public institution. The data for the patients' functional status are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Patient's functional status (degree of dependence) according to information provided by the caregiver.

At the start of the program, the burden perceived by the caregiver and scored with the Caregiver Burden Interview was 57.6±15.48 (n=173). Tables 2 and 3 show the percentages of respondents who scored highly on each item, and the distribution of the levels of burden of care.

About three-fourths (78.9%) of the caregivers who did not feel burdened according to the Caregiver Burden Interview were younger than 55 years, in comparison to 5.8% between 55 and 65 years, and 15.8% more than 65 years old. The differences were statistically significant at P<.05. No differences were found for relation to the patient, marital status or employment status of the main caregiver.

The evaluation questionnaires distributed at the final session of the program were completed by 134 caregivers, who considered the program to be valuable (mean overall score of 4.63 points out of a possible 5). Figure 2 summarizes the responses to the question "What was the best thing about the course?" According to participants, the aims that were achieved most effectively were contact with other persons with similar problems, and obtaining new knowledge and skills to improve the quality of care. Almost all caregivers (96%) were glad they had taken part in the program.

Figure 2. Caregivers' responses to the question "What was the best thing about the course?"

The effectiveness of the program in reducing the burden of care in the middle term could be studied for only 68 caregivers who completed the Caregiver Burden Interview before the intervention and again 3 months after the program. Mean score at the start of the program was 54.76±15.16, and mean score after the program was 53.02±12.55; this difference was not statistically significant. According to levels of burden of care, the percentage of caregivers with a heavy burden decreased from 37% at the start of the study to 34.8%, but the proportion of caregivers with a slight burden increased somewhat from 18.8% to 28.3%. The most significant difference, when we compared this subgroup of 68 caregivers with the whole sample of participants in the program, was found in the lower degree of dependence of patients (49.2% needed help with basic activities, versus 65.8% for the whole sample).

All health care professionals who participated in the intervention teams were satisfied with the group education experience, according to the results of the evaluation by these participants. The most frequent problems identified were in training the trainers and in managing groups of caregivers whose patients were in widely different stages of dementia. Problems related with training were identified in recruiting caregivers, generally because of suboptimal cooperation by other staff members at the health center, and in finding a convenient place to meet when caregivers were assigned to different health centers. Intervention groups set up in rural areas were particularly problematic in this respect.

Discussion

The ALOIS program was created initially to provide caregivers with an opportunity for training and to exchange ideas on the care of patient with dementia. A second aim was to support primary care professionals in the development of group education programs aimed at carers of persons with dementia. The objectives of the program were therefore less aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of this type of intervention, and more oriented toward the wider dissemination of such programs to provide professionals and caregivers with a reference instrument for similar activities. The considerable amounts of data from the evaluation that were lost reflected the less than optimal supervision of different teaching teams.

Another important limitation of the study is the heterogeneity among the caregivers we recruited, and who looked after patients with different types of dementia in widely differing stages. These factors made the training groups' work difficult at times, and made certain biases more likely. In addition, our study evaluated the burden of care only at the beginning and 3 months after the end of the program. We have no data on the subsequent course of the burden on caregivers, the demand for social services, or the appearance of specific disorders such as anxiety or depression.

The caregiver profile we obtained is very similar to that of other Spanish studies of caregivers of patients with dementia,18 neurodegenerative disease,7 or patients with different types of dependence.5,6 Evidently, this profile is slowly disappearing in Spain, and the enormous volume of work it represents does not seem to be absorbed by the currently inadequate social services system. This reinforces the need for interventions designed to facilitate the work of caregivers of patients with dementia.

It is noteworthy that more than 20% of the caregivers who described themselves as the principal carer did not live in the same household as the patient. In general, it is the daughters of patients who must look after their relatives, including one or both parents who live in a separate household. However, the burden of care was no greater in this subgroup of caregivers than in other relatives.

More than 60% of the caregivers received substantial help from other family members, but fewer than 5% received any type of institutional help. The EUROCARE19 study, which analyzed factors associated with the burden of care in different countries of the European Union, noted that the low level of formal help in Spain was one of the greatest sources of stress for caregivers of patients with dementia. In contrast, the high degree of informal help (compared to other countries) was a protective factor. Some studies of interventions for caregivers also considered the most appropriate social resources for each patient. It seems clear that in Spain, such individualized counseling might improve the results of these programs. It is true that social resources are scarce; however, what is no less true is that patients and caregivers are not referred as often as is desirable to available social resources.

Although studies of the burden of care are relatively common in the international literature, the Caregiver Burden Interview was validated in Spain only recently, by Martín Carrasco et al.9 The findings in the present study showed the burden to be heavier in our patients than in the aforementioned validation study. The study population used in Pamplona included caregivers of older patients with different psychiatric disorders, whereas our study population was more homogeneous, consisting mainly of caregivers of patients with dementia. When we compared the results for specific items, we found a much higher incidence in our caregivers of problems related to insufficient time, deterioration of social relationships, and stress produced by caregiving. Several studies have shown greater burdens of care in caregivers of patients with dementia as compared to caregivers of patients with other problems.20,21 Similarly, the total score and percentage value for burden of care were higher than in the EUROCARE study,19 both in general and for the subgroup of Spanish caregivers. This may be related with the fact that the caregivers recruited for our study were responsible for patients with recently diagnosed dementia, a factor that generally involves a lower burden of care.

In the present study we found differences between caregivers only in connection with age: the older the caregiver, the greater the burden of care. This difference was not found in other studies,22,23 although one study did find differences between men and women (with greater burdens being reported for the latter).23 In the present study the number of male caregivers was too small to detect differences between the sexes, if any differences exist. The EUROCARE study19 found the opposite association, i.e., a greater burden of care in younger caregivers. However, this study included only the patient´s spouse as caregiver, and in this subgroup the nature of the association may be different.

We found no differences between the results of the Caregiver Burden Interview at the beginning and the end of the program. However, a curious finding was that the subgroup of caregivers who completed both interviews had a lower initial burden of care, and the patients they cared for were in lower stages of dependence than the group as a whole. This may have skewed the results, as the caregivers who were likely to benefit most from this type of intervention may have been those with the greatest burdens of care. Even caregivers with a lighter burden of care responsible for patients in the initial stages of illness may suffer from increased anxiety because of contact with caregivers subjected to greater burdens, who describe problems that are more complex and which less experienced caregivers have not yet faced. This hypothesis is supported by the finding that in the subgroup who responded to both

the preintervention and the postintervention interview, the percentage of caregivers with a heavy burden of care decreased, while the percentage of caregivers with a slight burden increased.

Although some studies have reported significant reductions in the burden of care after individual13,14 and group psychological and educational interventions,15,24-26 Brodaty et al,16 in their recent meta-analysis, found no benefits in terms of burden of care. The problem with judging these findings lies in the variety of methods used in different studies, which involved different tests of the burden of care, different observation periods, and naturally different types of interventions. Some authors have proposed quality of life scales27,28 as the most sensitive instruments for measuring changes caregivers experience after this type of intervention. Future studies under the ALOIS program will use the SF-36 questionnaire as one of the evaluation instruments.

Despite the limitations noted above, the group education experience was judged useful by both caregivers and health professionals. The large number of caregivers and professionals currently involved in the program is a clear sign of the interest in this problem. The high levels of burden of care we detected should raise our awareness of the need to find more appropriate types of support for caregivers. The support they receive has direct repercussions on their own health as well as on the health of the persons they care for, and probably also on the health care system in Spain. Defining the best strategies for each type of patient and caregiver is a complex task. We believe our program will allow us to determine whether caregivers responsible for patients with more advanced stages of dementia are more likely to benefit from this type of intervention, as some authors have suggested.29