Biliary cystadenocarcinomas (BCAC) are extraordinarily uncommon tumors.1–6 Initially described by Willes in 1943, only about 150 cases have been published in the medical literature.2 Correct preoperative diagnosis is difficult, especially when it comes to differentiating them from their benign variation: biliary cystadenoma (BCA). We present a case of BCAC and a brief update of the literature.

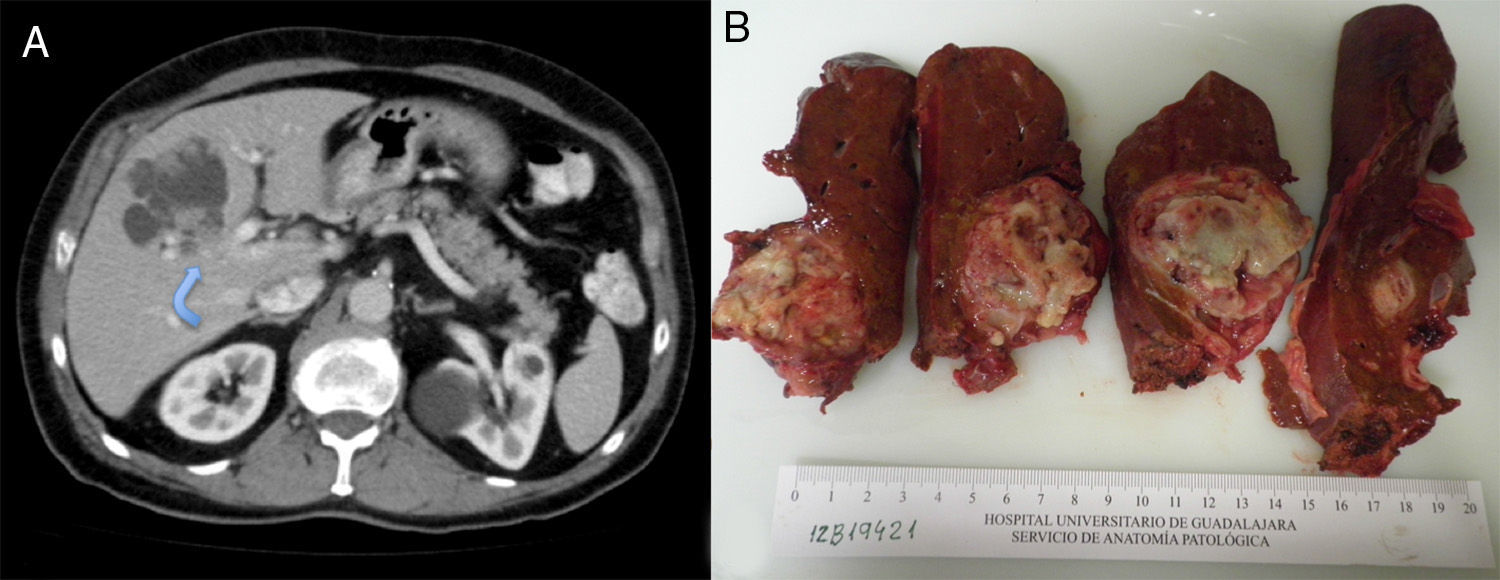

The patient is a 75-year-old male with the following medical history: prostate cancer (Gleason 6), in treatment with radiotherapy and hormone therapy; arterial hypertension; and hypercholesterolemia. He had no history of toxic habits. Follow-up abdominal ultrasound detected a complex hepatic cystic lesion with lobulated edges that was predominantly anechogenic and had posterior reinforcement; its interior contained multiple solid nodules. The patient presented no abdominal symptoms. Lab work-up was normal, except for CA19-9 (53IU/L). Serology for hydatidosis was negative. Abdominal CT revealed a cystic lesion measuring 65mm×55mm×45mm, located primarily in segment iv and partially in v and viii, with intracystic hyper-uptake wall nodules, slight intrahepatic bile duct dilatation due to direct compression and contact with the left portal vein (Fig. 1A). Gadolinium-enhanced MRI showed a cystic lesion with lobulated, well-defined edges, measuring 69mm×57mm×56mm. It had a heterogeneously intense signal that was predominantly hypointense in T1 and hyperintense in T2 (cystic areas) and, in the interior, several hypointense foci in T1 and T2 (intracystic solid wall nodules) (Fig. 1B).

Extended left hepatectomy was performed apart from segments v and viii since the left portal infiltration hindered mesohepatectomy. During the dissection of the parenchyma, we observed that the lesion infiltrated the right intrahepatic bile duct at the bifurcation of the right anterior and posterior sectors; therefore, the bile duct was resected and a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy was done. The postoperative period transpired without complications and the patient was discharged after 12 days.

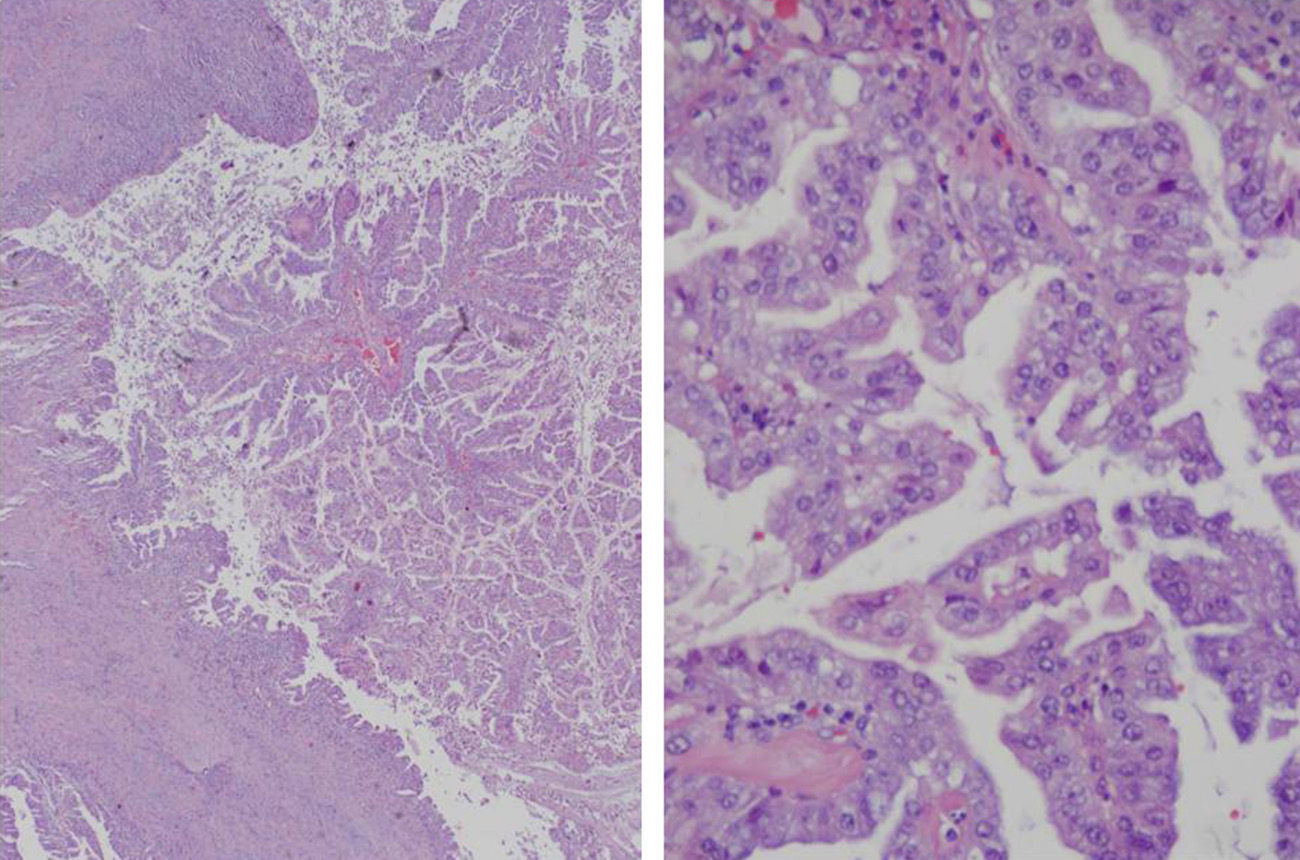

Macroscopically, the cystic mass was whitish with necrotic areas, measuring 6.4cm×5.3cm. Histology showed a cystic formation with intracystic papillary growths and infiltration of the underlying liver parenchyma, grade G1 (>95% gland formation) (Fig. 2). There was no perineural or vascular invasion. The neoformation was CK7 positive and CK20 negative. The final diagnosis was BCAC pT1pN0M0, stage i (TNM, 7th edition). Treatment was begun with oral capecitabine and radiotherapy. Six months later, the patient was asymptomatic.

BCAC is a hepatic neoplasm whose etiology is not clear.1,2,5–8 It does not favor either of the sexes, as 25%–72% of BCAC occur in males.1,2,5,6,8 Mean age is 60 (26–82 years).1,2,4–10 Its incidence is greater in Asia.1,2,4,6–10 It is not known whether BCAC evolves from a previous BCA or whether it is an initially malignant tumor. Two BCAC subtypes have been proposed: malignant transformation from a BCA with or without ovarian stroma, which is the most frequent type in women; and another initially malignant variation that originates from the intrahepatic bile duct or from a biliary malformation, which is more frequent in men.1–3,6

BCAC is characterized by being a single, large cyst that is usually multilocular with internal septa and papillary projections or wall nodules.1,5,8 Although uncommon, it may be connected with the bile duct or have intracystic bleeding.2,4,10 The location of BCAC is usually intrahepatic.1,5 Wang et al. have stated that the lesions not located in the left liver are usually benign.1,3 The size of BCAC ranges between 3.5 and 22cm.1,2,5,6,8

The most frequent symptom of BCAC is abdominal pain (90%–100%).1,2,5 Other symptoms are palpable mass, nausea, fullness, fever and occasionally jaundice or cholangitis.1,2,5,6 CA19-9 is elevated in 60% of patients with BCA and BCAC, so it is not able to differentiate between the two entities.1,6,7 CA19-9 is also high in the intracystic liquid.2,6,8 Other marker levels (CEA, CA242, CA50) are usually normal.1,6

The diagnostic methods that are usually used in BCAC are ultrasound, CT and MRI.1,3,5,10 PET has not been frequently used, although it seems to be highly sensitive. The differential diagnosis of BCAC includes hepatic hydatidosis, liver abscess, metastasis with cystic degeneration, intraductal papillary tumors of the bile ducts, von Meyenburg complexes, and even a simple cyst.2,7,8 But the true diagnostic difficulty lies in being able to differentiate between BCA and BCAC, which is essential to define the therapeutic strategy.1 The presence of wall nodules with hyper-uptake on CT, calcifications and papillary projections are suggestive of BCAC.2,6–8 Some patients are diagnosed after years of follow-up as BCA, or with the failure of incorrect therapeutic measures like puncture or fenestration.6 FNA provides a limited diagnostic capability, and there is a risk for dissemination along the needle pathway.1,3,8,10

In their series of 30 cases of BCA and BCAC, Wang et al. observed that the following factors were predictors of BCAC: age>60, male sex and recently progressing symptoms (less than 4 months). They also designed a point system to differentiate between both lesions. Although size had classically been considered a predictive factor for BCAC, it did not reach statistical significance.1

The treatment of BCAC is surgical resection with free margins.1,2,5,6,8 Due to the lesion size, major hepatectomies are frequently done.9 Other therapeutic procedures (fenestration, sclerosis) should be avoided.2 Enucleation, which is valid for BCA, should not be done in BCAC due to the need for free margins.8

The data on survival in BCAC are limited and confusing, with rates ranging from 25% to 100% after 5 years. There seems to be a correlation between survival, histologic subtype and patient sex. Thus, women with a BCAC that develops over a BCA with mesenchymal stroma seem to have a better prognosis, and men with an initially malignant tumor have a poorer prognosis.4,5 Radical resection is related with lower recurrence and longer survival.1 MUC2 positivity is considered a favorable prognostic factor.9 There is no valid information about which chemotherapy regimen is most recommendable.

Please cite this article as: Ramia JM, de la Plaza R, Pérez Mies B, Arteaga V, García-Parreño J. Cistoadenocarcinoma biliar. Cir Esp. 2015;93:e53–e55.