The use of continuous barbed sutures has facilitated the laparoscopic technique by reducing operative times for suture reinforcement1 and anastomoses, where their use is also considered feasible and safe.2,3 Barbed sutures have also been shown to not be inferior in terms of suture dehiscence, hemorrhage, or anastomotic stenosis.4

The ease of use, time savings and good results reported with barbed sutures motivated us, 20 months ago, to change our suture technique in laparoscopic (totally manual) gastrointestinal anastomoses during gastric bypass (GBP) and subtotal gastrectomy (STG) from continuous 3/0 monofilament sutures (Monocryl, Ethicon) to 3/0 barbed sutures (Stratafix, Ethicon).

In the literature, bleeding from the gastrojejunal anastomosis ranges between 1% and 11% depending on the technique used (manual, linear, circular), and the circular technique presents bleeding with the greatest frequency.5,6

We have observed an increase in cases of bleeding from laparoscopic gastrojejunal anastomoses, which we wanted to analyze.

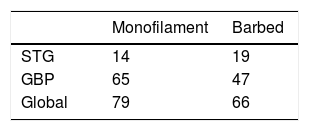

We have performed a total of 79 anastomoses with monofilament (14 STG and 65 GBP) and 66 with barbed suture material (19 STG and 47 GBP) (Table 1). No other modification to the surgical technique was made.

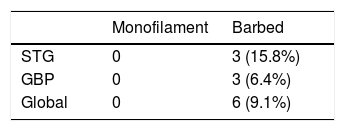

There was hemorrhage at the gastrojejunal anastomosis in 6 cases (9.1%) after the use of barbed suture, and in no case after the use of monofilament (Table 2). In 4 cases, this was resolved with endoscopic sclerosis. One case of a patient with Child class A cirrhosis due to NASH who was taking antiplatelet drugs required surgical suture after failure of endoscopic sclerosis, and one case was not endoscopically confirmed due to self-limitation.

A common characteristic is that the bleeding occurred after the sixth postoperative day and after discharge in most cases, so the cause or consequence of said bleeding coincided with gastric dilation. The only case of hemorrhage in the immediate postoperative period was the one that was self-limited.

Our hypothesis is that the barbed suture anchors do not allow for distension of the anastomosis and may damage it.

Despite the fact that a 9.1% rate of anastomotic bleeding falls within what has been published, we were surprised by this increase in bleeding after the change in suture material compared to our past results. Since our experience does not resemble what has been published, we believe it is interesting to share it with the rest of the surgical community, basically so that other groups may also express whether or not they have observed this complication.

Please cite this article as: Luna A, Rebasa P, Montmany S, Pascua M, Navarro S. Mayor incidencia de sangrado en anastomosis gastroyeyunal manual con sutura barbada. Cir Esp. 2021;99:617–618.