Sarcoidosis is a multisystem idiopathic disease characterized by the presence of epithelioid granulomas, with no crown of lymphocytes or central caseous necrosis. Hepatic involvement is uncommon, and radiology tests may detect lesions mimicking bile duct tumors.1,2

However, the finding of these granulomas is not exclusive of sarcoidosis; they can also develop in the lymph nodes to which a neoplasm drains; this phenomenon is known as a sarcoid reaction.3

Cholangiocarcinoma is the second most frequent primary hepatobiliary cancer. Its preoperative diagnosis is complex, resectability is uncertain in the presence of lymphadenopathies, and the definitive diagnosis is histopathological.2

We present the case of a patient with systemic sarcoidosis and hilar cholangiocarcinoma with regional lymphatic sarcoid reaction.

The patient is a 67-year-old male diagnosed with cutaneous sarcoidosis by biopsy and thoracic computed tomography (CT) showing diffuse bilateral pulmonary involvement, appearing as ground glass opacities, and bilateral and mediastinal hilar lymphadenopathies. With the diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis, the patient initiated corticoid treatment, leading to clinical-radiological improvement.

The 4-month workup showed: bilirubin 20.1mg/dL, direct 14.8, GGT 1920U/mL and Ca 19.9: 1492U/mL.

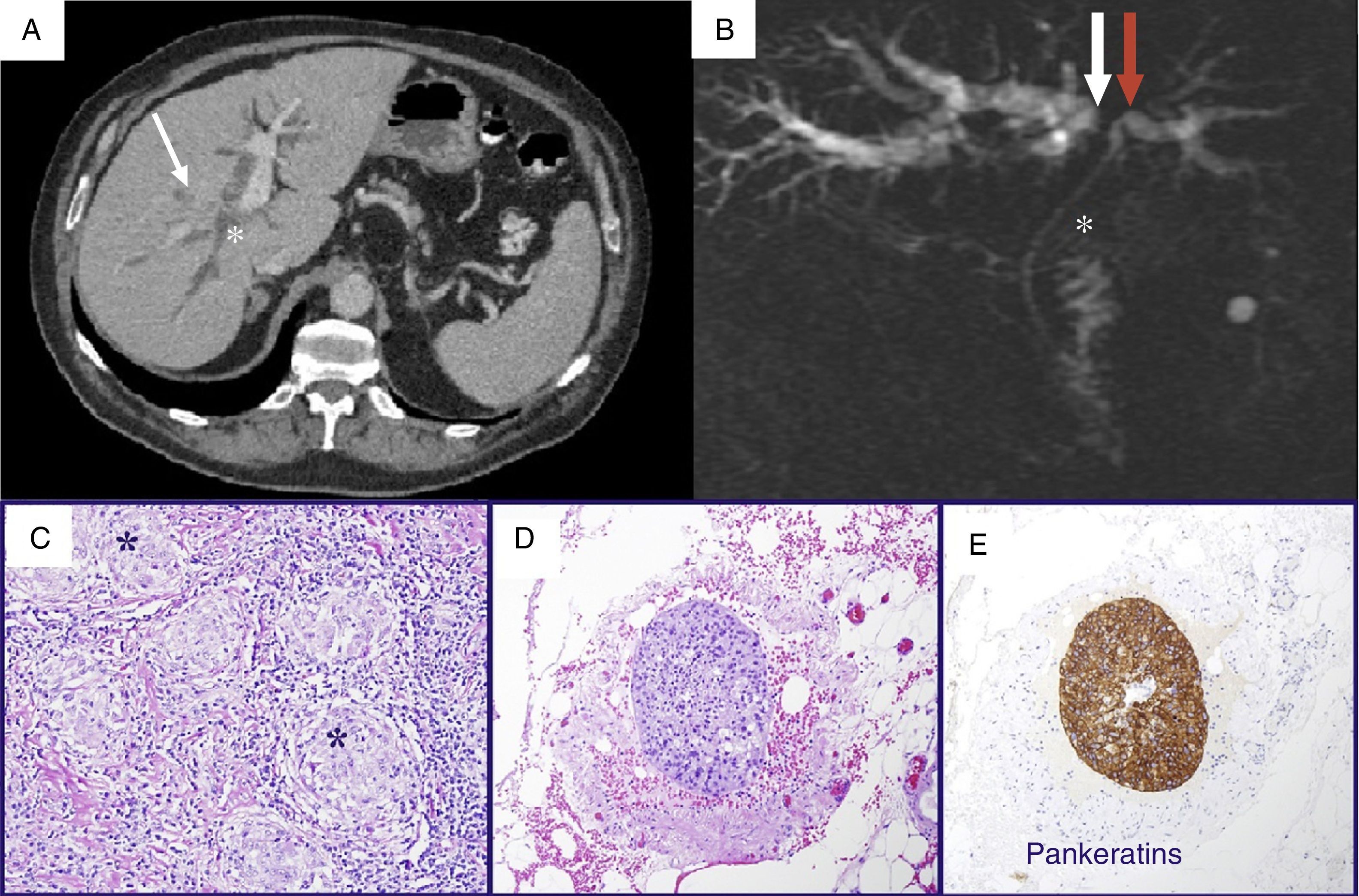

Abdominal CT and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) revealed: a 3cm mass in the confluence of hepatic ducts, with extension toward the right hepatic duct and portal vein, and dilatation of the intrahepatic bile duct, suggestive of Bismuth IIIa hilar cholangiocarcinoma (Klatskin tumor), and lymphadenopathies in the hepatic hilum (Fig. 1A and B).

(A) CT: dilatation of the intrahepatic bile duct (asterisk); infiltrating lesion surrounding the bile duct (arrow); (B) MRCP: dilatation of the intrahepatic bile duct with occlusion of the right branch (white arrow) and stenosis of the left (red arrow); common bile duct of normal size (asterisk); (C) detail of the sarcoid-type non-necrotizing epithelioid granulomas (*); (D) embolus of atypical epithelial cells in the interior of a perilymphatic vessel; the positivity for keratins (AE1-AE3) confirms its epithelial nature (E).

Cytology by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was suspicious for malignancy.

With the suspicion of a Bismuth IIIa cholangiocarcinoma, we decided to operate. During surgery, a 3cm mass was observed to encompass the common hepatic duct and right and left hepatic confluences, which infiltrated the right hepatic artery and both portal branches, along with perihilar and periportal lymphadenopathies. As the tumor was considered unresectable, perihilar lymphadenopathies were removed to confirm the diagnosis.

The pathology report identified sarcoid-type non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammation and perilymphatic vascular infiltration by atypical cells compatible with carcinoma (Fig. 1C and E).

A metallic stent was placed by means of ERCP, and treatment was initiated with a gemcitabine/cisplatin regimen.

Eleven months later, the patient was clinically asymptomatic with a normalized hepatic profile, showing stability of the disease and a drop in Ca 19.9–95.8U/mL.

Sarcoidosis mainly affects the lungs and lymph nodes of the pulmonary hilum. In general, it initially presents with bilateral hilar lymphadenopathies, pulmonary reticular opacities and skin/joint/ocular lesions. Although extrapulmonary involvement is common, it is rare for it not to coexist with lung disease.2 Diagnosis requires compatible clinical-radiological manifestations, exclusion of other alterations, and pathology findings of noncaseating epithelioid granulomas. Our patient met the criteria prior to the diagnosis of jaundice (dyspnea, skin lesion and positive histology).

The hepatic manifestations cover a wide spectrum: granulomas, generally asymptomatic, in 50%–80% of biopsies; 40% analytical alterations; and 5%–10% symptoms (hepatomegaly [most common], granulomatous cholangitis, cirrhosis, portal hypertension, jaundice.1,10 The bile duct can be especially affected by the synchronous presence of sarcoidosis and biliary cirrhosis/sclerosing cholangitis,5 primary sarcoidosis or compression due to perihilar lymph nodes with granulomatosis.1,2 If there is biliary stricture, the radiological findings are indistinguishable from a cholangiocarcinoma.2

Biliary stricture may be caused by a wide spectrum of lesions, including cholangiocarcinoma. It is essential to differentiate hilar lesions (Klatskin tumors, with a high rate of unresectability and poor prognosis) from “pseudo-Klatskin” lesions, which mimic these clinically and radiologically, sarcoidosis being among them.2 In cases of biliary stenosis, all the diagnostic methods available are required because in certain cases the distinction between malignant or benign lesions is complex. Some 5%–15% of hilar stenoses with suspected cholangiocarcinoma are identified as benign lesions in the definitive pathology study.11

Noncaseating epithelioid granulomas are not exclusive of sarcoidosis, and these lesions, with no systemic signs of sarcoidosis, fit within the context of sarcoid reaction. This finding has been documented in 4.4% of carcinomas, 13.8% of Hodgkin's disease and 7.3% of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma,3 even in the absence of metastasis. The sarcoid reaction can occur at any time during a neoplasia and can be found in the surrounding area of the tumor, lymph nodes or in organs such as the spleen, lungs or liver.3 Furthermore, these tumors can be overstaged if they are identified as metastases.

The differentiation between sarcoidosis and a sarcoid reaction associated with malignancy is complex as the systemic symptoms of sarcoidosis, anorexia and weight loss can also be due to a neoplasm and the granulomas are morphologically identical.9

There have been few case reports describing sarcoid reaction in association with biliary cancer (Table 1), and only one of them with preoperative diagnosis of sarcoidosis, such as the case that we describe.8 In our case, with a preoperative diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis, the biliary stenosis was due to a hilar cholangiocarcinoma with perilymphatic vascular infiltration, which may suggest that lymphatic granulomas are related to a histological reaction associated with a neoplasm.

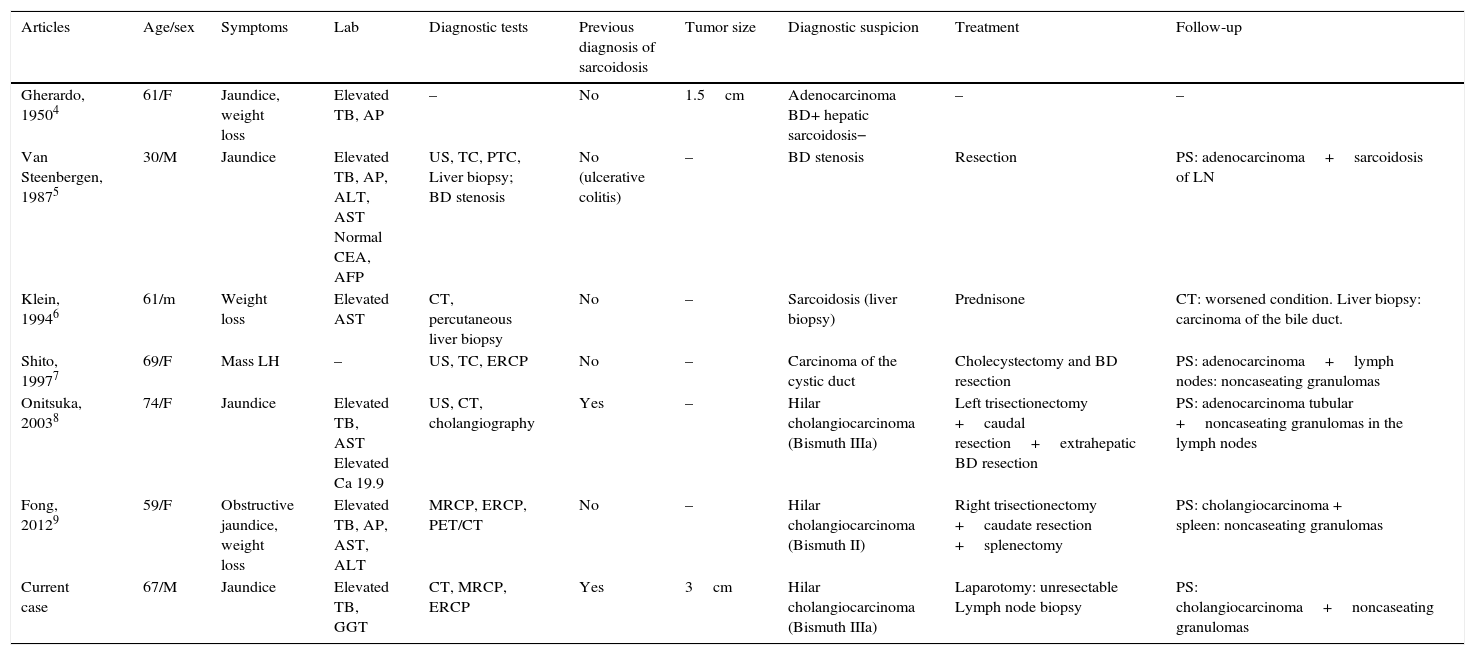

Published Cases of Cholangiocarcinoma and Sarcoid Reaction.

| Articles | Age/sex | Symptoms | Lab | Diagnostic tests | Previous diagnosis of sarcoidosis | Tumor size | Diagnostic suspicion | Treatment | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gherardo, 19504 | 61/F | Jaundice, weight loss | Elevated TB, AP | – | No | 1.5cm | Adenocarcinoma BD+ hepatic sarcoidosis− | – | – |

| Van Steenbergen, 19875 | 30/M | Jaundice | Elevated TB, AP, ALT, AST Normal CEA, AFP | US, TC, PTC, Liver biopsy; BD stenosis | No (ulcerative colitis) | – | BD stenosis | Resection | PS: adenocarcinoma+sarcoidosis of LN |

| Klein, 19946 | 61/m | Weight loss | Elevated AST | CT, percutaneous liver biopsy | No | – | Sarcoidosis (liver biopsy) | Prednisone | CT: worsened condition. Liver biopsy: carcinoma of the bile duct. |

| Shito, 19977 | 69/F | Mass LH | – | US, TC, ERCP | No | – | Carcinoma of the cystic duct | Cholecystectomy and BD resection | PS: adenocarcinoma+lymph nodes: noncaseating granulomas |

| Onitsuka, 20038 | 74/F | Jaundice | Elevated TB, AST Elevated Ca 19.9 | US, CT, cholangiography | Yes | – | Hilar cholangiocarcinoma (Bismuth IIIa) | Left trisectionectomy +caudal resection+extrahepatic BD resection | PS: adenocarcinoma tubular +noncaseating granulomas in the lymph nodes |

| Fong, 20129 | 59/F | Obstructive jaundice, weight loss | Elevated TB, AP, AST, ALT | MRCP, ERCP, PET/CT | No | – | Hilar cholangiocarcinoma (Bismuth II) | Right trisectionectomy +caudate resection +splenectomy | PS: cholangiocarcinoma + spleen: noncaseating granulomas |

| Current case | 67/M | Jaundice | Elevated TB, GGT | CT, MRCP, ERCP | Yes | 3cm | Hilar cholangiocarcinoma (Bismuth IIIa) | Laparotomy: unresectable Lymph node biopsy | PS: cholangiocarcinoma+noncaseating granulomas |

AFP: alpha-fetoprotein; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; PS: pathology study; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; TB: total bilirubin; CEA: carcinoembryonic antigen; ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; MRCP: magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; PTC: percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography; AP: alkaline phosphatase; GGT: gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; LH: left hypochondrium; F: female; M: male; PET/CT: positron emission tomography/computed tomography; CT: computed tomography; US: ultrasound; BD: bile duct.

Therefore, in cases of biliary stricture secondary to hilar lymphadenopathies, the differential diagnosis should include hilar cholangiocarcinoma and biliary involvement by sarcoidosis, without overlooking a lymphatic sarcoid reaction. It is fundamental to distinguish between metastatic lymphadenopathies and sarcoid reaction to avoid excluding a curative surgical option due to the suspicion of distant disease. Likewise, it is important to obtain tissue for histology studies before relegating a patient to palliative treatment.

FundingNo funding was received for the completion of this paper.

Please cite this article as: Manuel Vázquez A, Ramia JM, Latorre Fragua R, Alonso García S, Ramiro Pérez C. Colangiocarcinoma hiliar y sarcoidosis ganglionar periportal. Una asociación excepcional. Cir Esp. 2017;95:173–176.