The increase of quality of life, the improvement in the perioperative care programs, the use of the frailty index, and the surgical innovation has allowed to access of complex abdominal surgery for elderly patients like liver resection. Despite of this, in patients aged 70 or older there is a limitation for the implementation ERAS protocolos.

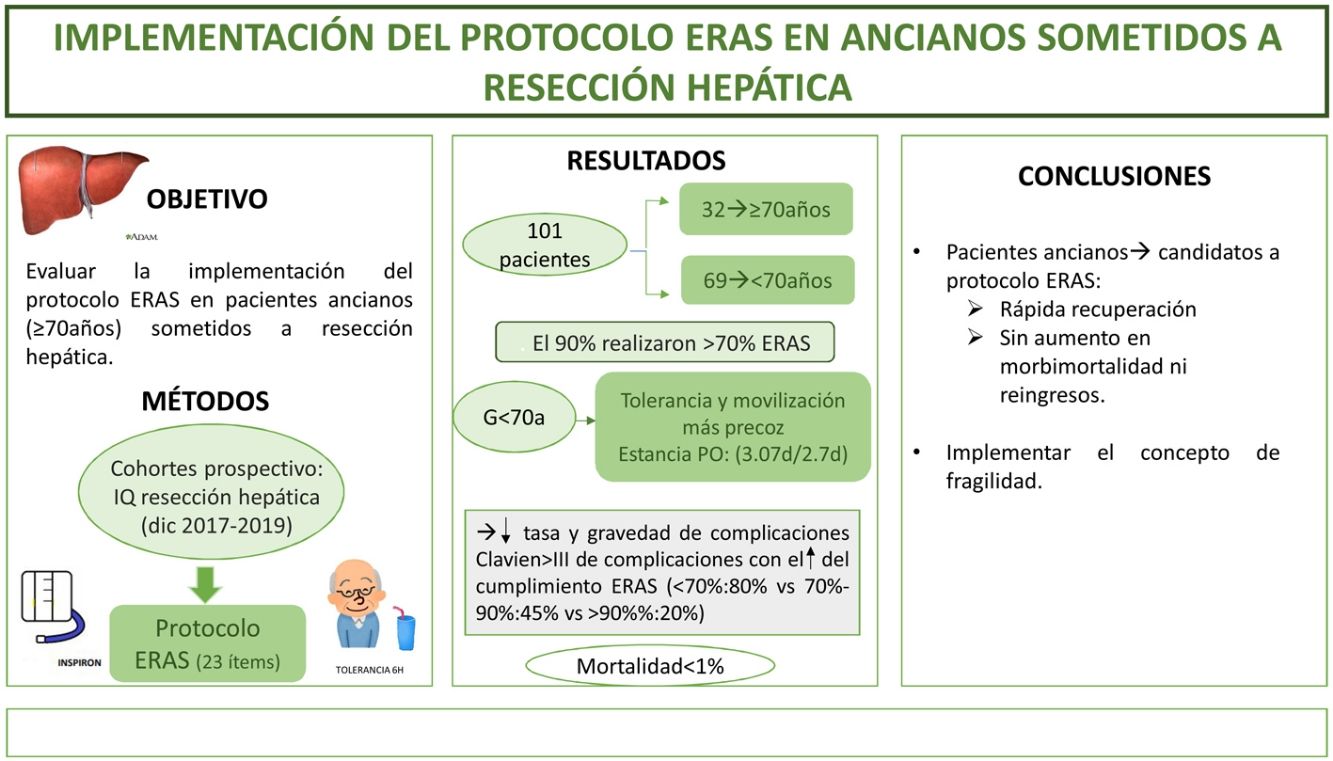

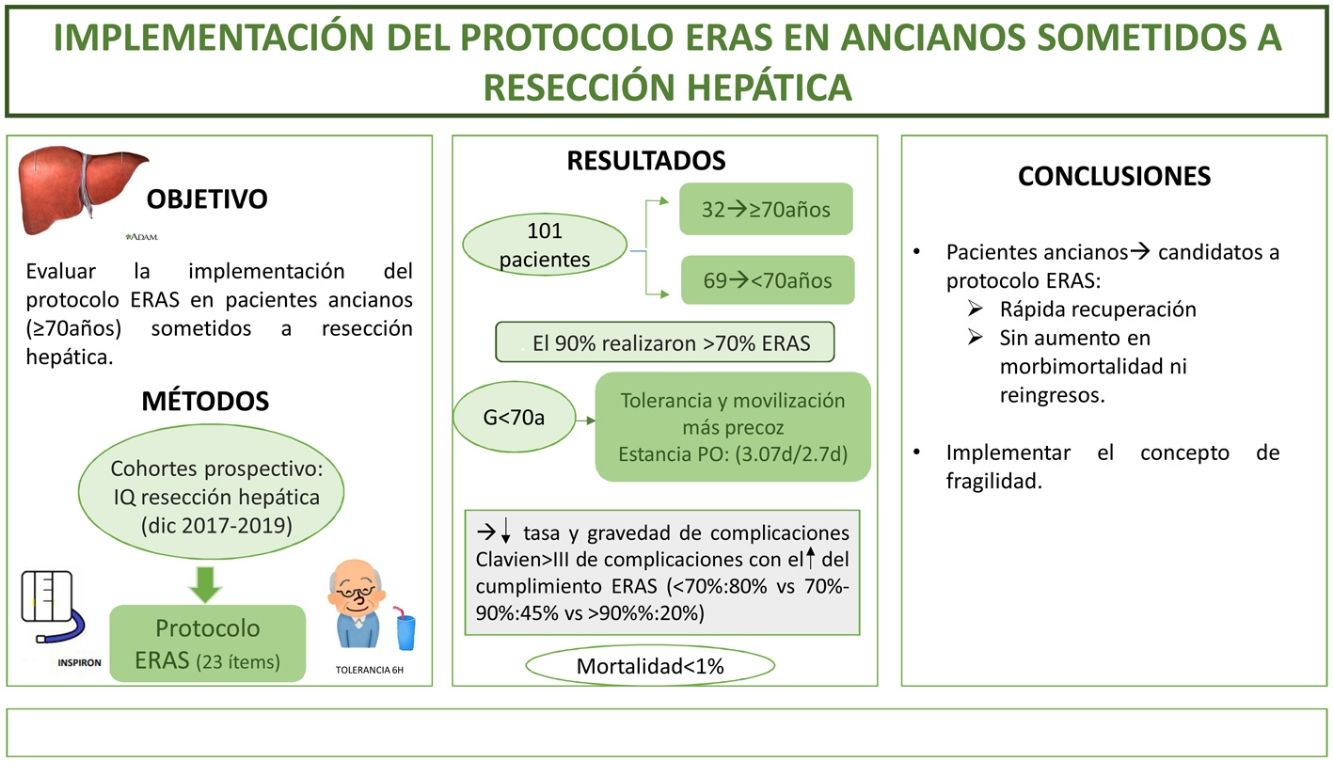

The aim of this study is to evaluate the implementation ERAS protocol on elderly patients (≥70 years) undergoing liver resection.

MethodsA prospective cohort study of patients who underwent liver resection from December 2017 to December 2019 with an ERAS program. We compare the outcomes in patients ≥70 years (G ≥ 70) versus <70 years (G < 70). The frailty was measured with the Physical Frailty Phenotype score.

ResultsA total of 101 patients were included. 32 of these (31.6%) were patients ≥70 years. 90% of the both groups had performed >70% of the ERAS. Oral diet tolerance and mobilization on the first postoperative day were quicker in <70 years group. The hospital stay was similar in both groups (3.07days/2.7days). Morbidity and mortality were similar; Clavien I-II(G ≥ 70:41% vs G < 70:30,5%) and Clavien ≥ III (G ≥ 70:6% vs G < 70:8.5%), like hospital readmissions. Mortality was <1%. ERAS protocol compliance was associated with a decrease in complications (ERAS < 70%:80% vs ERAS > 90%:20%; p = 0.02) and decrease in severity of complications in both study groups. Frailty was found in 6% of the elderly group; the only patient who died had a frailty index of 4.

ConclusionImplementation of ERAS protocol for elderly patients is possible, with major improvements in perioperative outcomes, without an increase in morbidity, mortality neither readmissions.

El aumento en la calidad de vida, la mejora en los cuidados perioperatorios, la aplicación del concepto de fragilidad y un mayor desarrollo de técnicas quirúrgicas permite a pacientes ancianos el acceso a la cirugía hepática. Sin embargo, la edad sigue siendo limitante para la implementación de protocolos ERAS en este grupo.

El objetivo del estudio es evaluar la implementación del protocolo ERAS en pacientes ancianos (≥ 70 años) sometidos a resecciones hepáticas.

MétodosEstudio de cohorte prospectivo que incluye pacientes intervenidos de resección hepática durante: diciembre 2017–2019 sometidos a un programa ERAS, comparando los resultados de pacientes ≥70 años (G ≥ 70) frente <70 años (G < 70). La fragilidad se midió con el score Physical Frailty Phenotype.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 101 pacientes, 32 (31,6%) correspondieron a G ≥ 70. El 90% de ambos grupos verificaron realizar >70% del ERAS. Se encontraron diferencias a favor del G < 70 en el inicio de tolerancia y la movilización activa el primer día postoperatorio. La estancia postoperatoria fue superponible (3.07días vs 2.7días). La morbimortalidad fue similar; Clavien I-II (G ≥ 70:41% vs G < 70:30,5%) y ≥ III (G ≥ 70: 6% vs G < 70:8.5%), al igual que los reingresos. La mortalidad global fue <1%. El cumplimiento del ERAS se asoció a un descenso en las complicaciones (ERAS < 70%:80% vs ERAS > 90%:20%; p = 0.02) y de la gravedad de las mismas en la serie global y en ambos grupos a estudio. El 6% del G ≥ 70 presentó fragilidad; el único paciente fallecido alcanzó índice de fragilidad de 4.

ConclusiónLos pacientes ancianos son candidatos a entrar en protocolo ERAS obteniendo una rápida recuperación, sin aumentar la morbimortalidad ni los reingresos.

In Spain, at the beginning of 2019, there were 8,908,151 people over the age of 65, representing 19% of the population, of whom 6% were over the age of 80. It is estimated that by 2068, more than 14.106 people will be over 65 years old, which will constitute almost 30% of the population.1 The increase in this age group is accompanied by an increase in the diagnosis of neoplastic diseases, their second cause of mortality.1 This social group has shown a marked improvement in their quality of life, which, together with improvements in perioperative care and surgical techniques, spearheaded by the introduction of the laparoscopic approach,2 has enabled them access to highly complex surgeries such as liver resections.

The implementation of multimodal rehabilitation protocols in different areas of abdominal surgery3–6 has led to a clear decrease in morbidity rates, earlier functional recovery, and a reduction in postoperative length of stay (LOS).

Age alone does not appear to be a predisposing factor for postoperative complications.7 The concept of frailty, understood as multisystemic physiological impairment and increased vulnerability to stressors, has been shown to be the most important predictor of postoperative outcome.8 There are multiple scores to define frailty; however, regardless of the definition and the combination of domains, frailty is significantly associated with an increased risk of postoperative morbidity and mortality after major abdominal surgery.9

Nevertheless, in routine clinical practice, age remains a limiting factor for the implementation of multimodal rehabilitation protocols (Enhanced Recovery After Surgery [ERAS] protocol) in major abdominal surgeries such as liver surgery.

This study aims to evaluate the results after the implementation of an ERAS protocol in elderly patients (≥70 years) undergoing liver resection (LR) versus younger patients (<70 years), in whom they were already routinely applied.

The primary objective of the study was to observe the results of implementing the ERAS protocol in elderly patients (G ≥ 70) undergoing LR and its influence on LOS, morbidity and mortality, and readmissions.

The secondary objective was to assess whether compliance with the ERAS protocol is related to fewer complications.

Material and methodsPatients and study designWe present a prospective cohort study in which we included patients undergoing LR without a combined technique to treat liver lesions, from December 2017 to December 2019, ≥18 years, who signed their informed consent and agreed to be included in the ERAS protocol. We obtained permission from the Provincial Research Ethics Committee of Malaga (n. 2099-N-19).

The following were excluded: patients with resection of another organ, haemodialysis, severe valvular heart disease, ejection fraction <35%, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) grade IV, Klatskin tumours, Associating Liver Partition and Portal vein ligation for Staged hepatectomy (ALPPS) and intraoperative unresectability.

Data analysedThe variables collected were demographics, aetiology, American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification (ASA), frailty, CHILD/Model for End Stage liver Disease (MELD), number of lesions, approach route, surgical technique, transfusion, surgical time, ERAS protocol, analytical controls, postoperative morbidity and mortality (Clavien–Dindo) and at 30 days, LOS, and readmission.

Patient managementAll patients were discussed in the Multidisciplinary Committee for Digestive Tumours, where they were considered candidates for surgery with curative intent.

ERAS programmeThe ERAS protocol was explained by the surgeons in the outpatient clinic (Table 1). Patients were given an information leaflet on the different periods and guidelines for their intervention. Prehabilitation was stressed based on (a) respiratory physiotherapy: deep breaths ≥4 times/day using an incentive spirometer; (b) motor physiotherapy: walking (30−60 min, 5 times/week), and (c) nutrition: high protein shakes were prescribed 3 times/day to all patients regardless of nutritional status, based on evidence of improved postoperative outcomes.10 The mean time between consultation and surgery ranged from 2 to 4 weeks.

ERAS programme.

| ERAS programme | |

|---|---|

| 1st Preoperative | |

| Outpatient consultation | Patient information: information about the process and the need for their involvement throughout the procedureInformed consent explanationInformation about the ERAS programme that they must understand and agreeDelivery of inspirometer and leaflet (Appendix B Annex 2) |

| Admission to the ward: (day prior to the surgical intervention) | Reduce preoperative fasting time (6 h)Carbohydrate intake the night beforeAnaesthetic pre-medication |

| 2nd Intraoperative | |

| Operating theatre | Pneumatic compression stockings as antithrombotic measureThermal blanket to prevent hypothermiaAntibiotic prophylaxisFluid therapy optimisationUse intravenous/epidural analgesiaRemove NGT at the end of surgeryReduce indications for drains after the surgical procedure |

| 3rd Postoperative | |

| Evening after surgery | Start oral intake in the evening 4−6 hours following surgeryEncourage early ambulation by starting on the evening of surgeryAvoid the use of opioids. Use analgesia as recommended by the anaesthetics department |

| 1st–3rd postoperative day | Remove NGT if not removed earlierRemove urinary catheterIncrease dietActive ambulationSerial blood analysis |

ERAS, Enhanced Recovery After Surgery; NGT, Nasogastric tube.

The ERAS protocol (Table 1) was used multidisciplinarily by the different professionals involved in this process.

AuditTo determine compliance with the ERAS protocol, as in the study by Pisarska et al.11 on adherence to the protocol, we considered compliance to be adequate at between 70% and 90% of the items established.

The entire multidisciplinary team involved in the ERAS protocol audited their part of the process. The principal investigator analysed the data obtained. Nursing: (1) On admission, the items that should have been carried out at home are analysed. (2) In the operating theatre, pre/intraoperative care is checked. At discharge, the anaesthesiologist records their performance on an Excel table. Intensivists collect data from the first 24 h (h). On the ward, the surgeons record clinical progress until discharge. Everything is recorded in the patient's electronic history.

FrailtyThe patients ≥70 years old underwent the frailty test, Physical Frailty Phenotype (PFP)12 which analyses 5 clinical characteristics: decreased lean body mass, grip strength, endurance, walking speed, and physical activity. Patients showing more than 3 characteristics are considered frail, 1–2 are pre-frail and 0 are non-frail. Complications in the different subgroups were analysed.

Discharge criteria and postoperative follow-upPatients had to meet certain criteria to be discharged: able to tolerate a solid diet, pain controlled with oral analgesia, adequate analytical controls (haemoglobin, leukocytes, liver enzymes, and synthesis factors), and actively mobile.

Follow-up was at one week with a nursing check-up, and at one month in the outpatient clinic. The data collected were degree of pain (visual analogue scale [VAS]), need for analgesia, complications, return to normal life, analytical control, and readmission rates.

AnaesthesiaFirst-line analgesics were used for postoperative pain control, regardless of the patient's aetiology, as described by Melloul et al.13 Whether opioids were used was at the discretion of the anaesthesiologist depending on the patient and the type of intervention. If they were required, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics were assessed before deciding which to use. Within the ERAS protocol, the following were indicated: epidural analgesia pump in open surgery and intravenous analgesia or intravenous analgesia pump in laparoscopy. Epidural catheters were not used in cirrhotic patients, due to the potential risk of haemorrhage secondary to thrombopenia and/or impaired coagulation.

SurgeryWe have used the laparoscopic approach for LR in our unit since 2004 6 and its use has gradually increased to 82% in 2019. In the open approach, an extended right subcostal incision is made, and in the laparoscopic approach, the French position is used for anterior segments and left lateral decubitus for segments VI–VII. The hepatic hilum is systematically prepared for the Pringle manoeuvre and intraoperative ultrasound is used.

Major liver resection (MLR) and minor liver resection were considered according to the definitions of the medical-surgical encyclopaedia.14

In patients with neoplastic disease, we used indocyanine green to delimit the hepatic region and the transection line. LR was performed using bipolar coagulation, ultrasonic and mixed dissector. We used 35 mm endo staplers to section the vascular pedicles.

Statistical analysisStatistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software was used for statistical analysis. Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages, and quantitative variables as means and standard deviation. Bivariate analysis was performed with Student's t-test for quantitative variables and χ2 for qualitative variables. A multivariate logistic regression model was performed taking postoperative complications as the outcome variable. A p-value < .05 was statistically significant.

ResultsA total of 116 patients were indicated for LR. Of these, 15 patients (13%) were excluded from the study due to intraoperative unresectability (7), diaphragmatic infiltration (3), and some form of intestinal suturing (5). A total of 101 resections were included in the study, of which 32 (31.6%) corresponded to G ≥ 70.

DemographicsBoth groups were homogeneous with respect to their demographic characteristics (Table 2). The surgical indication was similar in both groups, the most frequent cause being metastases from colorectal cancer (CRC) (G ≥ 70: 50% vs G < 70: 56%; p = .489), followed by hepatocarcinoma. The percentage of cirrhotic patients was also similar in the two groups (G ≥ 70: 34% vs. the <70 group (G < 70): 27%). Functionally 95% of the series were Child-Pugh A and the MELD ranged from 6 to 14. Although there were no statistically significant differences, the G < 70 had a higher portal hypertension (PHT) rate (G ≥ 70: 9% vs. G < 70: 12%). PHT was defined as patients with platelet counts below 80 × 109/l, presence of splenomegaly and/or varices on abdominal CT.

Demographic variables.

| ≥70 years (n = 32) | <70 years (n = 69) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (M/F) | 69% (22)/31% (10) | 65% (45)/35% (24) | p = .727 |

| ASA | |||

| I | 0% | 6% (4) | p = .372 |

| II | 47% (15) | 46% (32) | |

| III | 53% (17) | 48% (33) | |

| Cirrhosis* | 34% (11) | 27% (19) | p = .484 |

| MELD | 7 (6−14) | 6 (6–13) | p = .126 |

| Child A | 90% | 100% | p = .271 |

| PHT | 9% (3) | 12% (8) | p = .496 |

| Aetiology | p = .489 | ||

| CRC metastasis | 50% (16) | 56% (39) | |

| CHC | 37% (12) | 27% (19) | |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 6% (2) | 3% (2) | |

| Other | 6% (2) | 13% (9) | |

| Physical Frailty Phenotype | |||

| Not frail | 23 (71%) | ||

| Pre-frail | 7 (21%) | ||

| Frail | 2 (6%) | ||

Quantitative variables are expressed as percentages (n).

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification; CRC, Colorectal cancer; F, Female; HCC, Hepatocellular carcinoma; M, Male; MELD, Model for End Stage liver Disease; PHT, Portal hypertension (defined as patients with platelet count less than 80 × 109/l, presence of splenomegaly and/or varices on abdominal CT scan).

Patients diagnosed with metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) received CT according to the cancer diagnosis and treatment protocols of the Intercentre Clinical Management Unit of Regional University Hospital and Virgen de la Victoria of Malaga and the Oncology area of the Costa del Sol Hospital (Marbella) (Appendix B Annex 2). However, it was significantly higher in the G < 70 (G ≥ 70: 12% vs. G < 70: 32%).

FrailtyAll 32 patients of G ≥ 70 underwent the Physical Frailty Phenotype (PFP). Only 2 patients (6%) had a score of 4 and thus met the frailty criteria. A first patient aged 77 years, cirrhotic, with chronic renal failure (CRF) and moderate COPD underwent surgery for cholangiocarcinoma, requiring MLR. He died due to acute liver failure and exacerbation of his CRF. The second patient aged 73 years, with cirrhosis of the liver, underwent surgery for hepatocarcinoma, with limited resection. He presented disorientation and postoperative ileus.

ERAS complianceA total of 72% of the sample had correctly complied with >90% of the ERAS protocol (Table 3), with similar figures in both groups (G ≥ 70: 62.5% vs. G < 70: 78%; p = .135). There was a significant decrease in complication rate as ERAS compliance increased (ERAS < 70%: 80% vs. ERAS 70 %–90 %: 45% vs. ERAS > 90%: 20%; p = .002) and severity of Clavien > III complications (ERAS < 70%: 20% vs. ERAS 70 %–90 %: 8.2% vs. ERAS > 90%: 3.3%; p = .03).

ERAS protocol items.

| ≥70 years (n = 32) | <70 years (n = 69) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compliance with ERAS | p = .468 | ||

| 100% | 22% | 33% | |

| 70%–90% | 69% | 57% | |

| <70% | 9% | 10% | |

| Signed informed consent | 100% | 100% | |

| Preoperative counselling | 100% | 100% | |

| Preoperative nutrition | 100% | 100% | |

| Fasting for 6 h | 100% | 100% | |

| Pre-anaesthetic medication | 100% | 100% | |

| Compression stockings | 100% | 100% | |

| Antibiotic prophylaxis | 100% | 100% | |

| Perioperative steroids | 95% | 98% | |

| Glycaemic control | 100% | 100% | |

| Guided fluid therapy | 100% | 100% | |

| Laparoscopic surgery | 87% | 84% | |

| Nausea and vomiting prophylaxis | 100% | 100% | |

| Active warming | 100% | 100% | |

| Avoid drains | 47% | 60% | |

| Removal of intraoperative NGT | 93% | 94% | |

| Analgesia pump (epidural or intravenous) | 22% | 22% | |

| Adjuvant NSAIDs | 100% | 100% | ns |

| Respiratory physiotherapy | 100% | 100% | ns |

| Tolerance 6 h following surgery | 62% | 81% | p = .043 |

| Early mobilisation | 69% | 78% | Ns |

| Removal of UC on first postoperative day | 75% | 81% | Ns |

| Active mobilisation on first postoperative day | 38% | 67% | p = .041 |

| Audit | 100% | 100% | ns |

Quantitative variables are expressed in percentages (n).

ERAS, Enhanced Recovery After Surgery; ns, not significant; NGT, Nasogastric tube; NSAIDs, Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; UC, Urinary catheter.

We found significant differences in the onset of tolerance at 6 h (G ≥ 70: 62% vs. G < 70: 81%; p = .043) and in active mobilisation on postoperative day 1 (POD) (G ≥ 70: 38% vs. G < 70: 67%; p = .041) in favour of G < 70.

OperativeWe found no difference in intraoperative variables (Table 4). The approach was mainly laparoscopic: 85% in the series. The most commonly used surgical technique was limited resection, but notably both groups underwent almost 20% MLR (G ≥ 70: 19% vs. G < 70: 22%). The need for transfusion was <10%.

Intraoperative data, expressed in percentages, with the number of patients in brackets.

| ≥70 years (n = 32) | <70 years (n = 69) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laparoscopy | 87% (28) | 84% (58) | p = .651 |

| Conversion | 6.3% (2) | 1.4% (1) | p = .186 |

| Liver resection | p = .487 | ||

| MLR | 19% (6) | 22% (15) | |

| Limited resection | 59% (19) | 53% (37) | |

| Segmentectomy | 22% (7) | 16% (11) | |

| Left lobectomy | 0 | 4% (3) | |

| Cysto-pericystectomy* | 0 | 4% (3) | |

| Pringle | p = .292 | ||

| Yes | 90% (29) | 82% (15) | |

| Duration | 62 min (15–137) | 60 min (11–170) | |

| Transfusion | 12% (4) | 6% (4) | p = .246 |

| Blood loss | 400 cc (50–600) | 600 cc (50–800) | p = .134 |

| Surgery time | 210 min (70–400) | 240 min (120–450) | p = .576 |

| Drain | 53% (17) | 40% (28) | p = .238 |

cc, cubic centimetres; min, minutes; MLR, Major liver resection.

Morbidity and mortality were similar; Clavien I-II (G ≥ 70: 41% vs. G < 70: 30.5%; p = .258) and ≥ III (G ≥ 70: 6% vs. G < 70: 8.5%; p = .672). Overall mortality was <1%. We also found no differences in LOS or readmissions (Table 5). In the overall series, we analysed possible factors influencing the development of Clavien ≥ III complications: age, MLR, transfusion, surgical time, and MELD. Only the need for transfusion (HR: 1.399; 95% CI: 1.260–1.998; p = .049) showed an association).

Postoperative variables.

| ≥70 years (n = 32) | <70 years (n = 69) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complications | |||

| No | 53% (17) | 61% (42) | p = .248 |

| I/II | 41% (13) | 30.5% (21) | p = .258 |

| Ascites | 4 | 2 | |

| Disorientation | 3 | 0 | |

| Impaired kidney function | 2 | 2 | |

| Respiratory | 0 | 3 | |

| Anaemia (iron) | 0 | 2 | |

| Postoperative ileus | 1 | 3 | |

| Sinus tachycardia | 0 | 2 | |

| AF RVR | 1 | 2 | |

| Biliary fistula | 0 | 2 | |

| Transfusion | 1 | 1 | |

| Hyperbilirubinaemia | 0 | 1 | |

| Postoperative collection | 1 | 0 | |

| Jugular thrombosis | 0 | 1 | |

| III/IV | 3% (1) | 8.5% (6) | p = .672 |

| Haematoma | 0 | 1 | |

| Abscess | 0 | 1 | |

| Biloma | 0 | 2 | |

| Grade B liver failure | 0 | 1 | |

| HD instability | 0 | 1 | |

| Epistaxis through NGT | 1 | 0 | |

| Death | 3% (1) | 0% | p = .14 |

| Readmissions | 3% (1) | 10% (7) | p = .224 |

| Biliary fistula | 1 | 2 | |

| Postoperative collection | 4 | ||

| Fever syndrome | 1 | ||

| Length of stay (days) | 2.7 (1−6) | 3.07 (1−23) | p = .528 |

Quantitative variables are expressed as percentages (n).

AF, Atrial fibrillation; HD, Haemodynamic; NGT, Nasogastric tube; RVR, Rapid ventricular response.

ERAS protocols in liver surgery dates have been used since the beginning of the 21 st century.15 However, their incorporation into clinical practice has been slower than in other disciplines. Our group has been applying these protocols for more than a decade.6 The advent of laparoscopy and its benefits, clearly demonstrated at the Southampton Conference,16 has significantly boosted application of the ERAS protocol, allowing it to be used in subgroups in whom there was some reluctance, such as elderly patients.

Age alone should not be the criterion for assessing an elderly person. The concept of frailty is fundamental when considering surgery in these patients. Hewitt et al.17 published a meta-analysis of 2,281 patients aged 61–77 years in abdominal surgery, showing higher 30-day mortality for frail (8%)/pre-frail (4%) versus non-frail (1%) patients. Morbidity was more common in frail (24%) vs. pre-frail (9%) or non-frail (5%) patients. Sandini et al.,9 in a review of 1,153,684 major abdominal surgery patients, confirmed that frailty, regardless of definition, was associated with increased postoperative morbidity (OR: 2.56) and mortality (.57). The PFP score was used to measure frailty in the G ≥ 70. Only two patients were classed as frail. This frailty was related to non-compliance with the protocol, to the occurrence of complications, and to the one deceased patient in the series. We found no differences between pre-frail and non-frail.

A total of 72% of the series complied with >90% of the ERAS protocol, which was similar in both groups. Ninety per cent of patients in both groups verified completing >70% of the ERAS protocol. Therefore, age did not constitute a problem for compliance with the protocol. However, Takamoto et al.18 report an 82.5% compliance (target: discharge 6th POD), and indicate age >65 years (OR: 3.48) and blood transfusions (OR: 5.47) as independent factors for failure of the ERAS. The use the open approach, delayed tube and epidural catheter removal may have affected the discharge of the elderly patients.

As Pisarska et al.11 demonstrated in colorectal surgery, we observed a higher number of complications (ERAS < 70%: 80% vs. ERAS 70%–90%: 45% vs. ERAS > 90%: 20%; p = .02) and greater severity (Clavien > III; p = .03) when there was poorer compliance with the ERAS protocol.

Surgical technique was superimposable in both groups. We highlight the use of the laparoscopic approach (G ≥ 70: 87%), which was more than that published in these patients.19,20 Although the use of drains should be restricted in the ERAS protocol, 53% of G ≥ 70 required a drain, possibly determined by the 30% of cirrhotic and 19% MLR patients. Tufo et al.21 report using the ERAS protocol in liver surgery in 161 patients >70 years, with 61% use of drains, higher than our group, which may be explained by predominant use of the open route and higher number of MLR (29%).

Rapid introduction of diet and mobilisation after liver surgery under the ERAS protocol has been reported.15,21–23 We found differences in favour of G < 70 in tolerance at 6 h (G ≥ 70: 62% vs. G < 70: 81%). These differences disappeared on the first POD, with 97% full tolerance. We also observed differences in active mobilisation on the first POD (G ≥ 70: 38% vs. G < 70: 67%) in favour of G < 70, which again equalised on the second POD (G ≥ 70: 97% vs. G < 70: 98%). All patients spent their first 24 h in the intensive care unit (ICU) unaccompanied; this may have delayed these parameters, because as soon as they had a caregiver the data equalised. The literature shows that the absence of caregivers in elderly patients may raise morbidity and increase LOS.24 Nevertheless, G ≥ 70 had a similar LOS (G ≥ 70: 2.7days vs. G < 70: 3.07 days). Tufo et al.21 report an LOS of 6 days. They describe only 4% laparoscopic surgery, which could explain their increased length of stay. Chong et al.22 report in the ERAS group (mean age: 58 years) 30% of cirrhotic patients, with a LOS of 5 days, despite a 45% laparoscopic approach. The LOS was higher than ours despite a lower mean age and a similar percentage of cirrhotic patients. Wabitsch et al.,23 in their series of 67 patients >70 years, not using the ERAS protocol and using a minimally invasive procedure, describe a hospital stay of 9 days. Using the laparoscopic approach improves LOS,20–23,25 but it is under an ERAS protocol where elderly patients achieve true recovery, as we demonstrated in our series.

Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses26,27 have reported fewer complications after the application of ERAS protocols in liver surgery. We observed a slight increase in Clavien I/II complications in G ≥ 70, particularly due to ascites in cirrhotic patients and the typical disorientation of elderly subjects undergoing surgery, which improved with the presence of their caregivers, as described in literature.28 This did not prevent the adequate recovery or discharge of these patients. Clavien ≥ III complications (G ≥ 70: 6% vs G < 70: 8.5%) were lower than both the Tufo et al21 (11%) and Wang et al15 publications in ERAS and also lower than studies about the elderly and laparoscopy,19,23–25 which range from 11% - 24%. We believe that the lack of a laparoscopic approach in certain instances and the lack of ERAS protocols in others are what explain the increase in complications.

The limitations of this study are as follows: 1) As a single-center study, the recruitment of patients was consequently limited; 2) Due to the lack of data collection, we have not analyzed the influence of prehabilitation and the frailty score on the development of complications in the global series; 3) The use of the frailty score in clinical practice, especially in the elderly population, since its application allows us to select patients who would not benefit from surgical treatment.

ConclusionElderly patients are clear candidates for ERAS protocols. As described in the text, the implementation of the concept of frailty can help select patients for liver resection. Perfect compliance with ERAS guidelines will enable us to reduce complications. Although the clinical evidence is limited, we believe that laparoscopy is a fundamental pillar in the compliance with ERAS protocols, resulting in minimal complications and a rapid return to normal life.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.