As surgical resection remains the only hope for cure in pancreatic cancer (PC), more aggressive surgical approaches have been advocated to increase resection rates. Venous resection demonstrated to be a feasible technique in experienced centres, increasing survival. In contrast, arterial resection is still an issue of debate, continuing to be considered a general contraindication to resection. In the past few years there have been significant advances in surgical techniques and postoperative management which have dramatically reduced mortality and morbidity of major pancreatic resections. Furthermore, advances in multimodal neo-adjuvant and adjuvant treatments, as well as the better understanding of tumour biology and new diagnostic options have increased overall survival.

In this article we highlight some of the important points that a modern pancreatic surgeon should take into account in the management of PC with arterial involvement in light of the recent advances.

La resección quirúrgica representa en la actualidad la única posibilidad terapéutica para pacientes afectos de carcinoma de páncreas (CP). Procedimientos quirúrgicos agresivos han sido descritos en un intento de incrementar la resecabilidad. La resección venosa representa en la actualidad una técnica quirúrgica aceptada en centros con importante experiencia en cirugía pancreática. Por el contrario, la resección arterial en enfermos afectos de CP sigue siendo una técnica muy controvertida. La infiltración arterial en estos pacientes suele ser considerada un criterio de irresecabilidad. En los últimos años, importantes avances en la técnica quirúrgica y en el tratamiento postoperatorio de estos pacientes han permitido reducir la morbimortalidad de las resecciones pancreáticas. Por otra parte, notables mejoras en el tratamiento neoadyuvante y adyuvante así como un mayor conocimiento en la biología del tumor además de nuevas opciones diagnósticas han permitido mejorar la supervivencia.

En el presente artículo, destacamos importantes puntos que un cirujano moderno debe de considerar para tratar a afectados de CP con infiltración arterial.

In Western countries, pancreatic cancer (PC) is the fourth and fifth cause of cancer-related death in men and women respectively, with more than 100 000 deaths every year in Europe and the U.S.A.1,2 Approximately 80%–90% of PC are locally advanced lesions or have systemic spread at the time of diagnosis. For patients susceptible to surgical treatment, as long as free margins are achieved, surgery is the only treatment which can offer prolonged survival.3

Vascular resection in pancreatectomy for PC is a controversial area. Venous involvement, as long as venous reconstruction is possible, is a technically complex factor, but as a concept it should not determine unresectability. Arterial involvement has long been a contraindication for surgical resection, due to a high morbimortality rate and limited oncological benefit. Recently, a small number of groups have been changing this criterion.4–7 The factors which have contributed towards this change are the standardisation of surgical procedures, the participation of general surgeons with broad experience in vascular surgery and the centralisation of pancreatic surgery in reference hospitals.

The anatomical location of the pancreas and its proximity to the large abdominal blood vessels influence arterial involvement in tumour formation processes. The common hepatic artery (CHA), the coeliac trunk (CT) and the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) are the vessels most frequently affected by the tumour process. In certain cases, either because of tumour spread itself or because of the presence of vascular anatomical variants, other arteries such as the right hepatic artery (RHA) are affected.4

DiagnosisPreoperative staging is a particularly important step in patients with PC. Its purpose is to establish lesions which are considered borderline resectable (BRPC), those which require neoadjuvant treatment and cases where the tumour is inoperable or unresectable.

Portal/mesenteric venous or arterial involvement was the established criterion for defining BRPC in the first definition made of this concept.8 Different classifications have been subsequently described.9–11 In all of them, BRPC or unresectable lesions are defined by arterial involvement.

Computerised axial tomography (CT), PET/CT and endoscopic ultrasound-guided (EU) fine needle biopsy have been demonstrated as suitable methods for diagnosing and staging PC.11 CT and EU are also considered necessary tests to provide information on arterial involvement in PC patients.12

The inclusion of arteries in the tumour mass or the combination of a greater than 50% involvement of the arterial circumference with irregularity or stenosis of the blood vessel wall is radiological criteria for arterial involvement. However, tomography assessment of the condition of the arteries in some PC patients is difficult.13 Very often CT does not manage to identify arterial or venous involvement14 which is in fact relatively frequent (21%–64%).15,16

Sugiyama et al. have reported that EU is more precise in identifying portal vascular involvement than CT, ultrasound and angiography.17 Other groups have reported similar conclusions.18,19 However there is no unanimity on this criterion. Vascular involvement is far more difficult to assess using EU,19,20 which has a reported sensitivity of 50%–100%20–23 and a specificity of 58%–100%.20,23

The diagnostic precision of magnetic resonance for vascular involvement is very similar to that of CT.24,25 Therefore this diagnostic technique is reserved for patients where CT is contraindicated; iodine allergy, renal failure or pregnancy.

Surgical Management of Vascular InvolvementSuperior Mesenteric ArteryFinal confirmation of vascular infiltration is determined by surgical exploration. In standard cephalic duodenopancreatectomy, arterial involvement is usually seen on transecting the neck of the pancreas.

The “artery first” approach is a technical modification which enables early identification of arterial involvement in CP patients.26 The SMA is dissected first. The neck of the pancreas and the stomach are divided in the final part of the resection. Plenty of different techniques have been described under this term.27–35

In groups which consider arterial involvement an absolute contraindication for surgical resection, this artery-first approach is necessary in an attempt to avoid the late detection of arterial spread. When this occurs, the surgeon has two options: (1) to consider the cancerous lesion unresectable, or (2) to resect the lesion, leaving the tumour adhered to the affected vessel. A macroscopically positive resection margin (R2) is always associated with poorer survival.36

In groups where arterial involvement is not a criterion for unresectability, the artery-first approach is not as important. However, if it is used, vascular control of the SMA and the SMV is always achieved from the start of surgery; this is advisable in patients with locally advanced tumours.

The most frequent anatomical anomaly of the hepatic artery is a replaced right branch arising from the SMA, which occurs in 9.8%–21% of the normal population.37 The artery-first approach also enables the early identification and preservation of this anomaly.

In PC, involvement of the SMA appears in localised legions, principally in the uncinate process. This involvement is generally limited to the most distal part of the artery. Involvement of the proximal part of the SMA near where it stems from the aorta generally occurs in large lesions where the SMV has also usually been infiltrated.

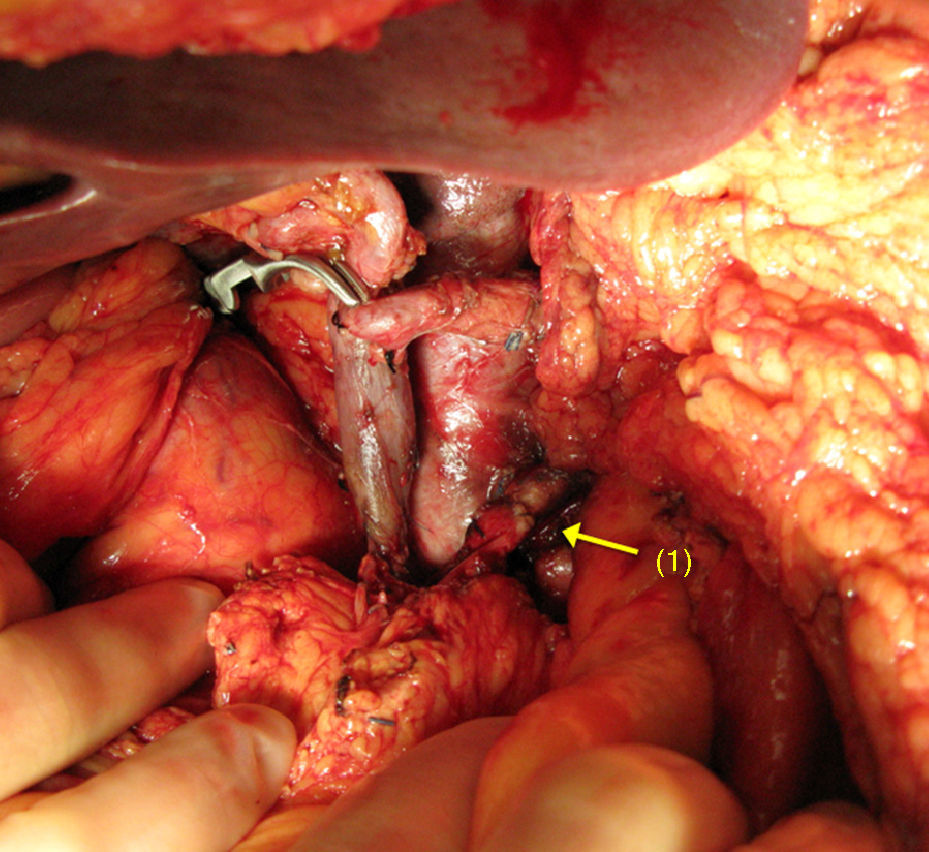

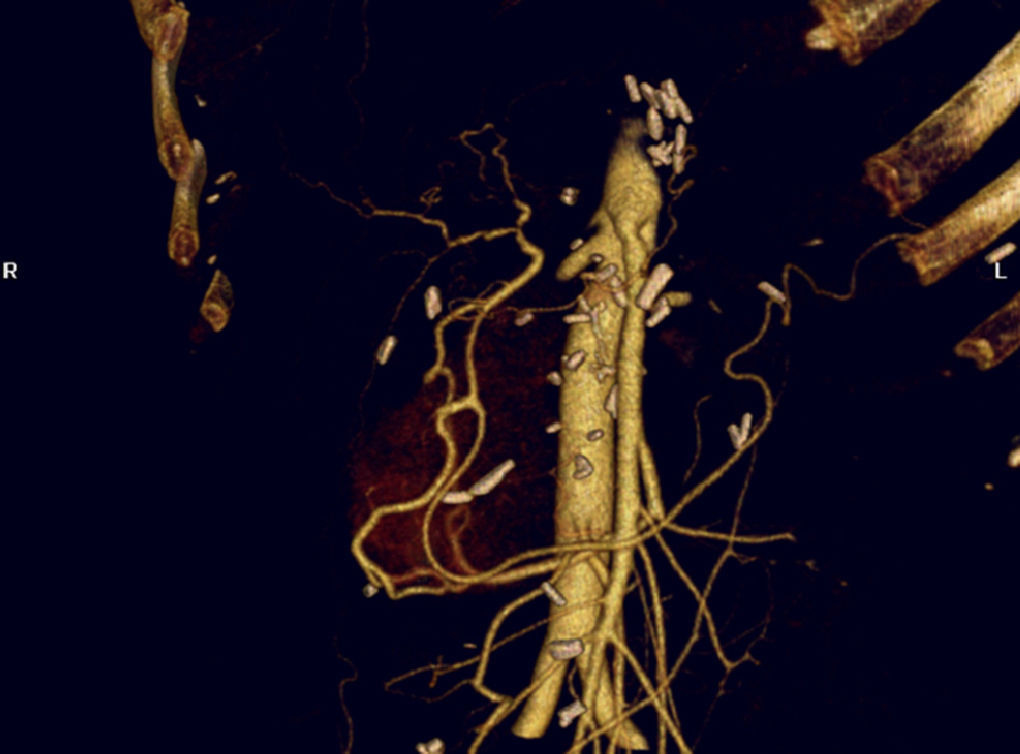

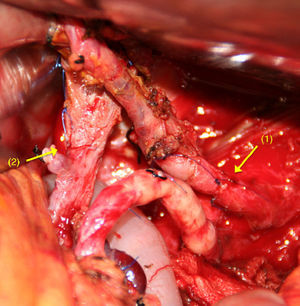

When there is spread to the SMA, reconstruction is performed by end-to-end anastomosis (Fig. 1). Mobilising both ends enables tension-free arterial reconstruction. Vascular grafts are seldom used in these types of tumours.

There is little world experience with this situation and it is reduced to groups with a high volume of pancreatic surgery.3,38–44

Coeliac TrunkDistal pancreatectomy associated with splenectomy45 is the standard oncological resection for tumours of the body and tail of the pancreas. Resection is combined with excision of the coeliac plexus, the lymph-nerve plexus which surrounds the superior mesenteric vessels and the regional lymph nodes around the pancreas. Occasionally vascular resection has to extend to a section of the portal vein, the left adrenal gland, the middle colic vessels and the infiltrated part of the adjacent organs.

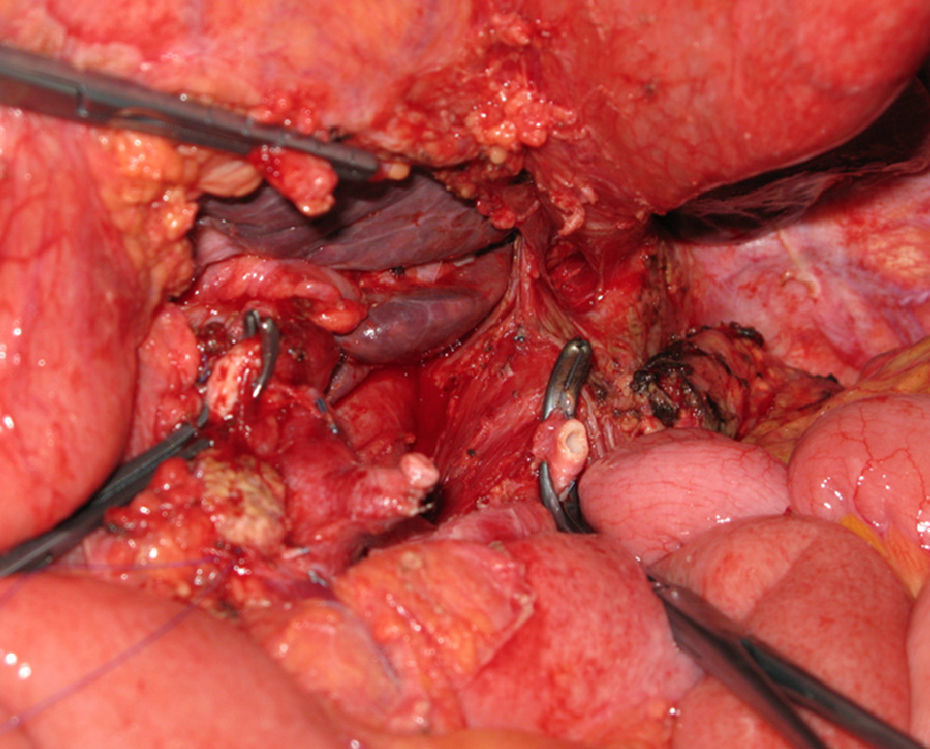

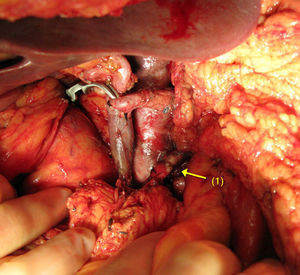

Distal pancreatectomy with en bloc resection of the CT has been widely adopted in pancreatic surgery in recent years (Fig. 2). Reported for the first time by Appleby in 1953 to achieve a radical lymphadenectomy around the coeliac axis in advanced gastric tumours,46 it was adopted by Nimura for the treatment of pancreatic tumours of the pancreatic body.47 In 1991, Nagino48 et al. and Hishinuma et al.49 described modifications to the technique in order to preserve the stomach if it had not been invaded by the PC. Until 2003, fewer than 25 cases had been described in the medical literature.47–50,53,56,58–60 Since then, the number of patients has slightly increased, although experience is limited to a small number of groups.51,52,54,55,57,61,62

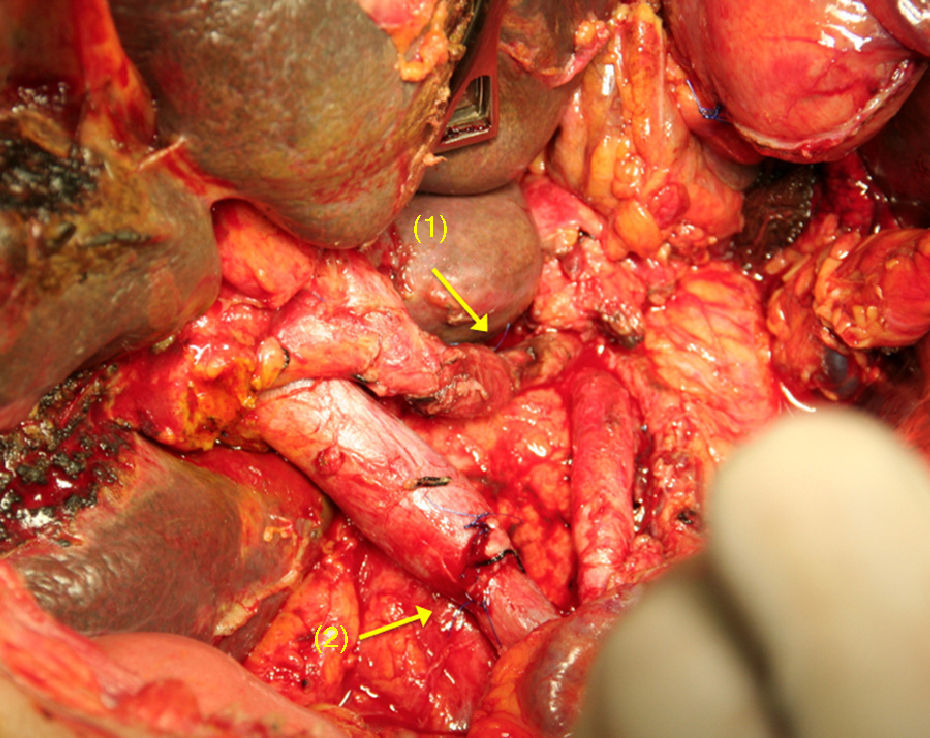

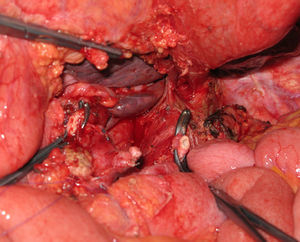

The challenge of the procedure lies in performing the resection of the coeliac trunk with its 3 visceral branches, preserving adequate arterial flow to the liver.56,63,64 In Appleby's operation, hepatic vascularisation should be assessed and preserved during surgery (collateral blood supply from the SMA through the pancreaticoduodenal arcades and the gastroduodenal artery). If it is not possible to preserve vascularisation, the liver should be rearterialised in order to prevent ischaemic consequences in the liver56,63,64 (Fig. 3). Similarly, the right gastric and gastroepiploic arteries should be preserved to ensure blood supply to the stomach.

After clamping the CHA an arterial pulse should be detected in the hepatoduodenal ligament. After that it can be resected, and the gastroduodenal artery is always preserved to ensure adequate blood supply to the liver. The presence of an arterial pulse in the hepatic hilium is usually associated with the confirmation by intraoperative Doppler ultrasound of intrahepatic arterial flow. It is considered that there should be an arterial flow greater than 22cm/s in order to prevent hepatic ischaemia and postoperative liver failure.63

In certain cases where after clamping it is observed that there is: (1) no arterial flow at the hepatic hilium level, (2) a change of liver colour and consistency (3) no intrahepatic arterial flow (intraoperative Doppler ultrasound), it is recommended that the CHA should be reconstructed. Obviously the other reason for rearterialisation of the liver is when a total duodenopancreatectomy is performed due to technical or oncological circumstances.

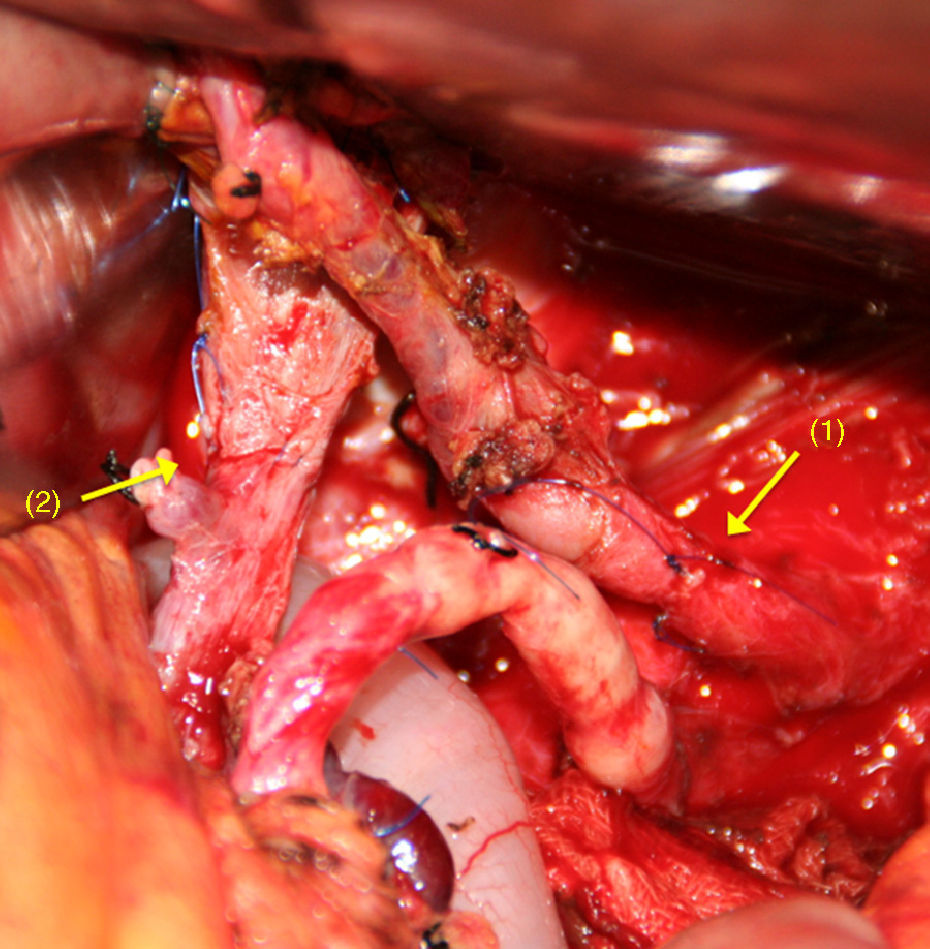

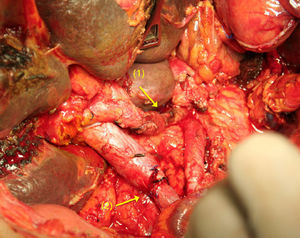

After dividing the CT and the CHA, and after extensive mobilisation of the proximal and distal artery ends,65–70 a tension-free, end-to-end anastomosis is performed (Fig. 4). If this is not possible, an autogenous51,56 (splenic, middle colic or gastropiploic artery) or synthetic71 vascular graft imposition can be performed.

The advantages of performing the Appleby procedure are: (1) resectability is increased, achieving a number of radical R0 resections which would not be possible without this procedure; (2) the patient's quality of life is improved through suitable control of the disabling pain which is characteristic of the presence of cancer of the pancreatic body and (3) there is the possibility of prolonged survival.

Right Hepatic ArteryAn RHA arising from the SMA is located in the area behind the pancreatic head, and runs through the right lateral area of the portal vein.72–74

This anatomical variation should be known preoperatively.75 Inadvertently injuring an anomalous RHA can cause major complications in the early postoperative period (biliary fistula, ischaemia or the formation of liver abscesses) or later (stenosis of the bilioenteric anastomosis).76,77

This anatomical anomaly poses a surgical challenge for PC patients. Not resecting a replaced or accessory RHA during a duodenopancreatectomy can occasionally result in an incomplete resection. Furthermore, single arterial ligation might be associated with significant morbidity. It can only be performed on patients who have a type-six arterial anomaly according to Michel's classification.72,78,79

Several publications have reported that the resection and reconstruction of the RHA is possible and safe.80,81 If the section or lesion is in its most distal part, the diameter and characteristics of the artery make it difficult to perform vascular reconstruction. In this situation it is advisable to perform this using a microsurgical technique. In the area of digestive surgery, especially gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary pancreatic surgery, surgeons are occasionally faced with the need to reconstruct blood vessels of very small diameters82–86; they very often require the help of plastic surgeons in order to do so. Therefore, it is a valuable asset for any surgical department if general surgeons have acquired experience in microsurgery techniques and this offers a solution to major vascular problems.

Preoperative Vascular EmbolisationPreoperative embolisation has been performed on patients with an RHA arising from the SMA, with the intention of increasing hepatic blood flow through the left hepatic artery.87 Collateral circulation develops ten days after embolisation. If possible, surgery should be postponed until this collaterality is sufficient to prevent liver complications secondary to ischaemia. In our opinion and that of other groups,88 this technique should be selectively indicated for patients for whom it is suspected, due to technical circumstances, that safe arterial reconstruction is not possible.

Another different aspect is preoperative embolisation in patients with PC which involves the coeliac trunk. With the intention of avoiding arterial reconstruction after radical resection, embolisation of the CHA can be performed preoperatively aimed at developing collaterality originating from the SMA.89 This is an excellent alternative for patients for whom, due to anatomical or technical circumstances, surgical reconstruction cannot provide adequate arterial flow to the liver. Without reconstruction, “natural hepatic arterialisation” after pancreatectomy with resection of the CT develops in very few days (Fig. 5).

Minimally Invasive SurgeryVascular resection in patients with PC using minimally invasive surgical techniques poses a real surgical challenge. Despite the little experience in this field with laparoscopic surgery, the results obtained with venous resections90 offer hope for the future. The only reference on arterial resection using this approach was performed in two stages.91

Robotic-assisted surgery (RS) is an excellent alternative within minimally invasive surgery. Since it started in 1997,92 it has progressed constantly and progressively and has revolutionised the concept of modern surgery. RS offers a solution to many of the shortcomings of laparoscopic surgery.93

Many of the greatest advances in RS have taken place in the area of pancreatic surgery.94–97 Using this innovative robotic system, it has been possible to undertake highly complex procedures with similar results to those obtained with open surgery.94,95,98

It has been possible to undertake resection of the mesenteric-portal axis using the robotic-assisted system with satisfactory results.95,99 For Appleby's operation using robotic assistance, Guilionotti99 performed a posterior approach towards the coeliac trunk described in open surgery.54 Although the 2 surgical procedures performed were undertaken for locally advanced tumours, the surgical time and intraoperative blood loss were appropriate to the characteristics of this complex surgical procedure.

Justification for Performing Arterial Resections in patients With Pancreatic CancerTechnical JustificationOne of the major complications of radical pancreatic surgery is the formation of a pseudoaneurysm.100–103 This is manifested clinically by spontaneous rupture into the peritoneal cavity or the gastrointestinal tract.104,105

In the absence of complications after pancreatic reconstruction, it has been suggested that skeletisation of the visceral arteries when excising perineural and lympho-adipose tissue could affect the involvement of the vascular wall.104,105 In other cases it might be associated with an adjacent focus of infection.106

It is not always easy to recognise the arterial lesion during radical surgery. Very often after performing extensive vascular dissections, the artery presents a transmural haematoma or a loss of its consistency might be observed. In these cases resection of the affected artery is fully justified. However the presence of an artery with apparently normal characteristics after complex dissection does not rule out a parietal lesion. Alteration of the arterial wall makes it necessary to resect the affected vessel.

The prognosis of patients with postoperative arterial pseudoaneurysms depends on 3 factors: the time it occurred, early diagnosis and the possibility of treatment using interventional radiological techniques.104,107–110

Oncological JustificationSignificance of Arterial InvolvementThere are two different theories which define the meaning of vascular involvement and justify which therapeutic approach to use:

- 1.

Arterial involvement defines a more aggressive tumour. Micrometastatic spread not noticed at the time of presentation limits the oncological benefit of radical surgery, even when the resection was R0.111,112

- 2.

Vascular spread does not predict a more aggressive tumour, but reflects the location of the lesion. This theory would enable radical resection to be justified including the arterial axis.113,114

With the exception of large tumours, it appears that the presence of arterial involvement is not connected with risk factors and traditional prognoses, such as metastatic lymph spread, perineural infiltration, tumour differentiation and the high rate of resections with positive margins.115 Rehders et al.115 have also confirmed that there is no correlation between vascular spread and the incidence of spread of tumour cells. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that the presence of arterial involvement is an indicator of unfavourable tumour topography rather than an indicator of adverse tumour biology.

Importance of Free MarginsThe surgical margins of PC patients are not well defined.116 According to the NCCN clinical guidelines,11 the margins in pancreatoduodenectomy are: SMA margin (retroperitoneal/uncinate), posterior margin, margin of the portal vein groove, the portal vein itself, margin of pancreatic neck transection and the margin of the bile duct.

Although there is some debate as to the significance of the involvement of the margins in terms of the patient's prognosis,117,118 the objective of surgical treatment of PC must always be to achieve an R0 tumour resection. Although long-term survival after R1 resections has been described,121–124 any incomplete resection (R1 or R2) should be considered palliative.124,125 R1 or R2 resection should be avoided by undertaking a suitable preoperative study and appropriate surgical technique.119,120

Arterial resection appears to be justified in a select number of patients in whom otherwise it would not be possible to achieve an R0 resection.

Lack of Knowledge of the Evolution of the TumourThe mean survival achieved for PC patients after radical surgical resection has slightly improved. Current total survival at 5 and 10 years is 19% and 10% respectively.126 The former is 2% greater than that described by the same group 21 years earlier.127 Other groups have achieved similar outcomes.128,129

Prolonged survival has been described recently for PC patients after multidisciplinary treatments.128,130,131 In general these patients have small tumours which are well differentiated, with no lymph node involvement and with no involvement of the resection margins. But this is not always the case. Prolonged survival has been observed in patients with locally advanced and even metastatic tumours.130 These results demonstrate the heterogeneity of the biological behaviour of PC. In certain cases, it is the biology of the cancer rather than the traditional factors that determines the patients’ prognosis.

Performing radical surgery with free margins is an essential requirement in order to achieve prolonged survival.

Current Status of Neoadjuvant and Adjuvant TreatmentsNew and interesting concepts which have arisen in recent years have produced changes in the therapeutic strategy of patients with PC:

PC is the result of successive accumulation of genetic mutations.132 The majority of patients carry one or more genetic defects.133,134

PC has a dense stroma.135,136 Pancreatic stellite cells (or myofibrobasts) play a major role in the formation and renewal of the stroma.135–138 Not simply a mechanical barrier, the stroma participates in the formation, progression and production of metastasis.135,136 Stroma cells express a variety of proteins which have been associated with resistance to treatment and as a consequence poor prognosis. These proteins constitute new therapeutic targets.139,140

Therapy directed at modifying the stroma facilitates an increase in tumour vascularisation with the consequent increase in the diffusion of drugs into pancreatic tumours. This aspect improves the efficacy of these drugs.141

Within the tumours, a subset of neoplastic cells has been identified with pluripotential properties.142,143 In PC these stem cells (1%–5% of the tumour population) are resistant to radiation and chemotherapy, which could explain the lack of efficacy of these treatments and the recent interest in directing treatment at these specific cells.143,144

Gemcitabine has been the treatment of choice for PC145 in recent years. Several agents with mechanisms of action different from gemcitabine have been combined in a variety of clinical studies without improved results.146,147 The only agent which in combination with gemcitabine has demonstrated a slight improvement in the survival of PC patients is erlotinib (molecular epidermal growth factor inhibitor).148

New concepts with regard to the characteristics of CP are opening up new and promising therapeutic perspectives. The new drugs include small signalling pathway inhibitor molecules and oncogenes.149–156 The recognition of the fact that both the tumour microenvironment and the neoplastic stem cells are critical elements of PC has resulted in the development of agents such as hedgehog signalling pathway inhibitors which block these components.136,141,143,144 The possibility of there being preclinical models available to review the complexity of this disease helps to establish strategies and priorities for the development of new drugs and innovative therapies.157 The genomic complexity of PC demonstrates the heterogeneity of this type of cancer and makes it advisable to use individualised treatment methods.158

ConclusionsA great many medical experts have long remained sceptical and non-discriminatory with regard to PC, especially in terms of the role played by radical surgery. This attitude was justified by the limited available therapies. It is clear that the situation has changed as a consequence of the advances achieved in the last 10 years. These advances which have repercussions on the medical and surgical specialities involved in the diagnosis and treatment of the tumour process enable the problem to be viewed differently.

Current results cannot be considered exceptional as yet. However, it is undeniable that a novel and promising therapeutic pathway has been established based on biological knowledge of the tumour process.

Surgeons involved in these morbid processes cannot remain on the sidelines of this new situation. The principal objective of the surgical treatment they provide should be to achieve resections with free margins. This can completely change the patients’ expectations. The vascular structures affected by the tumour should not be an impediment to undertaking radical treatment in a very select group of patients. Precise knowledge of the site of the tumour and suitable experience in digestive tract and vascular surgery will be decisive factors in achieving good outcomes from surgical treatment.

For selected patients with PC, arterial resection should be considered as a technical option in the current surgical arsenal. This technical possibility should be incorporated into modern multidisciplinary treatment. Its use outside this context is questionable.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare and have received no funding.

The authors would like to thank Isabel de Salas and Pablo Ruiz for their collaboration in this article.

Please cite this article as: Vicente E, Quijano Y, Ielpo B, Duran H, Diaz E, Fabra I, et al. ¿Sigue representando la infiltración arterial un criterio de irresecabilidad en el carcinoma de páncreas? Cir Esp. 2014;92:305–315.