This multicentre observational study aimed to compare outcomes of anterior resection (AR) and abdominal perineal excision (APE) in patients treated for rectal cancer.

MethodsBetween March 2006 and March 2009 a cohort of 1598 patients diagnosed with low and mid rectal cancer were operated on in the first 38 hospitals included in the Spanish Rectal Cancer Project. In 1343 patients the procedure was considered curative. Clinical and outcome results were analysed in relation to the type of surgery performed. All patients were included in the analysis of clinical results. The analysis of outcomes was performed only on patients treated by a curative procedure.

ResultsOf the 1598 patients, 1139 (71.3%) were underwent an AR and 459 (28.7%) an APR. In 1343 patients the procedure was performed with curative intent; from these 973 (72.4%) had an AR and 370 (27.6%) an APR. There were no differences between AR and APR in mortality (29 vs 18 patients; P=.141). After a median follow up of 60.0 [49.0–60.0] months there were no differences in local recurrence (HR 1.68 [0.87–3.23]; P=.12) and metastases (HR 1.31 [0.98–1.76]; P=.064). However, overall survival was worse after APR (HR 1.37 [1.00–1.86]; P=.048).

ConclusionThis study did not identify abdominoperineal excision as a determinant of local recurrence or metastases. However, patients treated by this operation have a decreased overall survival.

El objetivo de este trabajo observacional multicéntrico ha sido comparar los resultados de la resección anterior (RA) y la amputación abdominoperineal (AAP) en el tratamiento del cáncer de recto.

MétodoEntre marzo de 2006 y marzo de 2009, 1.598 pacientes diagnosticados de un tumor del tercio medio o inferior de recto fueron operados en los primeros 38 hospitales incluidos en el Proyecto del Cáncer de Recto de la Asociación Española de Cirujanos. La cirugía se consideró curativa en 1.343 pacientes. Los resultados clínicos y oncológicos se analizaron con relación al tipo de resección. Todos los pacientes fueron incluidos en el análisis de los resultados clínicos; para el análisis de los resultados oncológicos solo se consideraron los pacientes con operaciones curativas.

ResultadosEn 1.139 (71,3%) de los 1.598 pacientes se practicó una RA y en 459 (28,7%) una AAP. De los 1.343 pacientes operados con intención curativa, en 973 (72,4%)se practicó una RA y en 370 (27,6%) una AAP. No hubo diferencias entre RA y AAP en la mortalidad operatoria (29 vs. 18 pacientes; p=0,141). Con un seguimiento de 60.0 (49,0–60,0) meses no se encontraron diferencias entre ambas operaciones en la recidiva local (HR 1,68 [0,87–3,23]; p=0,12) ni en las metástasis (HR 1,31 [0,98–1,76]; p=0,064). Sin embargo, la supervivencia global fue menor con la AAP (HR 1,37 [1,00–1,86]; p=0,048).

ConclusiónEste estudio no ha identificado la AAP como factor determinante de recidiva local ni de metástasis, pero sí de la disminución de la supervivencia global.

In the mid and low rectal cancer surgery, sphincter-preserving surgery is the most widely used option.1,2 However, there are patients in whom this option is not possible because they present bulky, locally advanced or very low tumours. In addition, there are patients whose defecatory function is expected to be inadequate if continuity is restored. In such situations, the conventional abdominoperineal resection (APR), originally described with the resection of the levator ani, is indicated mainly in tumours of the lower third.3,4

Although these surgical procedures are not directly comparable, some studies show that patients treated by APR have a worse prognosis than those treated by anterior resection (AR).5,6 However, other studies indicate that there are no differences,7–10 or that, at least, local recurrence rates are similar in both procedures.11

The different oncological outcomes may have a multifactorial origin, depending on patient and tumour characteristics,12 and also on the surgical technique used,13 especially if APR is performed in a synchronous manner.14 Based on the above, there is no evidence yet that APR, in itself, has worse oncological outcomes than AR.

The purpose of this observational study, conducted within the framework of the Rectal Cancer Project of the Spanish Association of Surgeons has been to analyse the differences in the results of both types of surgery.

Material and MethodsThis multicentre observational study has been conducted within the framework of the Rectal Cancer Project of the Spanish Association of Surgeons. This teaching initiative was begun in 2006 with the intention of teaching mesorectal excision surgery to multidisciplinary groups of surgeons, pathologists and radiologists from hospitals belonging to the public health system that treat rectal cancer. A more detailed description of it has been recently published.15

This cohort includes 1598 patients diagnosed with low and mid rectal cancer, treated either by conventional APR or AR, between March 2006 and March 2009, in the first 38 hospitals included in the project. Surgery was considered potentially curative in 1343 patients, who underwent a locally radical procedure (R0 and R1), with tumour-free margins or microscopic invasion of them, in the absence of metastasis. Follow-up was performed until March 2014.

All the patients presented a rectal adenocarcinoma located between 0 and 12cm from the anal margin, as measured by rigid rectoscopy during removal of the rectoscope, or, mainly, by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).16 Due to the small number of patients with an emergency operation (5), these were not included in any analysis. Neoadjuvant therapy, generally long-course chemoradiotherapy, was administered routinely to patients with stages II and III. The usual contraindications of this treatment were the following: advanced age, ischaemic heart disease and previous pelvic radiotherapy.

Although follow-up frequency was left to the discretion of each one of the participating hospitals, in general, it was performed every six months during the first two years, and annually thereafter until completing five years. Generally in these visits, the CEA level was determined, a thoracic and an abdominal CT were performed and, on an annual or biennial basis, a colonoscopy was performed. When recurrence was suspected, the diagnosis was confirmed by MRI of the pelvis and positron emission tomography. Follow-up information was sent to the centralised project registry on an annual basis.

Outcome variables were as follows: (a) clinical: operative mortality, complications and reoperations; and (b) oncological: local recurrence, metastases and overall survival.

DefinitionsLR was defined as pelvic disease recurrence, including the anastomosis and perineal wound, regardless of whether the patient had distant metastases. An isolated recurrence in the ovaries was considered as metastasis.

Overall survival was defined as the time from surgery to death or last follow-up of the patients who had not died.

The tumour stage was determined by the TNM classification (American Joint Committee on Cancer [AJCC] stages I–IV; 5th edition).17

The project was approved by the Ethics Committees of the centres included in the study.

Statistical AnalysisContinuous variables are presented as mean and standard deviations. Categorical variables are presented as absolute values and percentages.

The results related to LR, metastasis, and survival rates were presented as the total number of events. It was considered that patients were at risk of experiencing the listed events until death, lost to follow-up due to a change in city of residence, or termination of follow-up at five years. The incidence of these events was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method.

After assessing the proportionality and linearity of the hazard ratios (HR), event-specific HR modelling was performed using the Cox proportional-hazards regression model. Potential confounders, such as age, sex, tumour location in the rectum, neoadjuvant therapy and tumour stage, were included in the models. HR is presented with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI).

All significant variables were included in the final analysis. Confounding variables with a marginal association (P<.15) were included in the model and were only excluded if they did not significantly change the probability of the model or the estimates of the remaining variables. If a variable was significant in the analysis of LR but not on survival or vice versa, it was included in both regression models.

Data were analysed using the R statistical package, version 2.11 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

ResultsThis cohort includes 1598 patients treated by conventional APR or AR between March 2006 and March 2009 in the first 38 hospitals included in the Rectal Cancer Project of the Spanish Association of Surgeons.

Clinical OutcomesThe analysis of the clinical outcomes of both surgeries was performed with data obtained from 1598 patients. Out of them, 1139 (71.3%) were treated by AR and 459 (28.7%) by APR. There were no differences between AR and APR regarding operative mortality (29 vs 18 patients; P=.141), or rates of reoperations performed in the postoperative period (112 [9.8%] vs 37 [8.1%]; P=.270). However, the postoperative complication rate was higher in APR (445 [39.1%] vs 236 [51.4%]; P<.001).

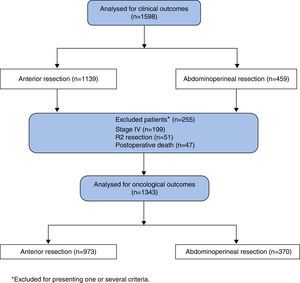

Oncological OutcomesThe analysis of oncological outcomes was performed in 1343 patients with potentially curative surgery, excluding 255 patients due to one or several of the following reasons: metastases at diagnosis (n=199), R2 resections (n=51) or postoperative deaths (n=47) (Fig. 1).

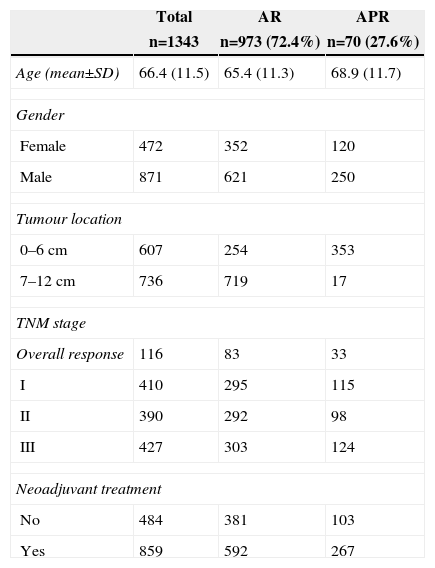

The characteristics of this cohort, where surgery was considered potentially curative, are listed in Table 1. In 973 patients (72.4%), an AR was performed, and 370 (27.6%) underwent an APR. The APR was performed in 18 (2%) tumours of the middle third and in 364 (58.2%) tumours of the lower third.

Characteristics of the 1343 Patients Operated on With Curative Intent.

| Total | AR | APR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=1343 | n=973 (72.4%) | n=70 (27.6%) | |

| Age (mean±SD) | 66.4 (11.5) | 65.4 (11.3) | 68.9 (11.7) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 472 | 352 | 120 |

| Male | 871 | 621 | 250 |

| Tumour location | |||

| 0–6cm | 607 | 254 | 353 |

| 7–12cm | 736 | 719 | 17 |

| TNM stage | |||

| Overall response | 116 | 83 | 33 |

| I | 410 | 295 | 115 |

| II | 390 | 292 | 98 |

| III | 427 | 303 | 124 |

| Neoadjuvant treatment | |||

| No | 484 | 381 | 103 |

| Yes | 859 | 592 | 267 |

APR, abdominoperineal resection; AR, anterior resection.

With a follow-up of 60.0 months (49.0–60.0), the cumulative incidence of LR was 6.22% (7.61–4.81), metastasis was 18.44% (20.61–16.21) and overall survival was 74.46% (76.89–72.11). The results of the Cox regression analysis are presented in Tables 2–4. This analysis showed that the APR itself did not influence the occurrence of LR (HR 1.68 [0.87–3.23]; P=.12)] or metastases (HR 1.31 [0.98–1.76]; P=.064). However, overall survival was lower with APR than with AR (HR 1.37 [1.00–1.86)]; P=.048).

Risk Factors for the Appearance of Local Recurrence.

| No event | Event | Hazard ratio | Univariate | Hazard ratio | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=1270) (94.5%) | (n=73) (5.4%) | 95% CI | P | 95% CI | P | |||

| Age (10 years) | 6.63 (1.1) | 6.73 (1.1) | 1.12 | 0.91; 1.37 | .298 | 1.07 | 0.87; 1.37 | .525 |

| Gender (reference: female) | ||||||||

| Male | 825 (65.0) | 46 (63.0) | 0.94 | 0.59; 1.51 | .805 | 0.99 | 0.62; 1.60 | .983 |

| Tumour location (reference 7–12cm) | ||||||||

| 0–6cm | 568 (44.7) | 39 (53.4) | 1.45 | 0.92; 2.30 | .114 | 1.22 | 0.64; 2.30 | .547 |

| Neoadjuvant treatment (reference: no) | ||||||||

| Yes | 816 (64.3) | 43 (58.9) | 0.78 | 0.49; 1.24 | .228 | 0.80 | 0.49; 1.29 | .357 |

| TNM stage (reference: stage I) | ||||||||

| (5.4%) Complete response | 114 (8.9) | 2 (2.7) | 0.76 | 0.17; 3.54 | .730 | 0.83 | 0.18; 3.90 | .813 |

| (5.4%) II | 371 (29.2) | 19 (26.0) | 2.32 | 1.05; 5.12 | .038 | 2.42 | 1.09; 5.36 | .029 |

| (5.4%) III | 384 (30.2) | 43 (58.9) | 5.52 | 2.69; 11.3 | <.001 | 5.72 | 2.78; 11.76 | <.001 |

| Surgical technique (reference: anterior resection) | ||||||||

| Abdominoperineal resection | 341 (26.9) | 29 (39.7) | 1.86 | 1.16; 2.98 | .009 | 1.68 | 0.87; 3.23 | .12 |

Risk Factors for the Appearance of Metastases.

| No event | Event | Hazard ratio | Univariate | Hazard ratio | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=1118)(83.2%) | (n=225)(16.7%) | 95% CI | P | 95% CI | P | |||

| Age (10 years) | 6.64 (1.15) | 6.60 (1.14) | 1.01 | 0.90; 1.13 | .872 | 1.01 | 0.90; 1.13 | .858 |

| Gender (reference: female) | ||||||||

| Male | 722 (64.6) | 149 (66.2) | 1.09 | 0.83; 1.43 | .551 | 1.13 | 0.85; 1.49 | .404 |

| Tumour location (reference 7–12cm) | ||||||||

| 0–6cm | 487 (43.6) | 120 (53.3) | 1.47 | 1.13; 1.90 | .004 | 1.40 | 1.00; 1.98 | .052 |

| Neoadjuvant treatment (reference: no) | ||||||||

| Yes | 704 (63.0) | 155 (68.9) | 1.22 | 0.92; 1.62 | .161 | 1.31 | 0.98; 1.76 | .064 |

| TNM stage (reference: stage I) | ||||||||

| Complete response | 113 (10.1) | 3 (1.33) | 0.35 | 0.11; 1.14 | .080 | 0.30 | 0.09; 1.00 | .051 |

| II | 333 (29.8) | 57 (25.4) | 2.19 | 1.40; 3.42 | .001 | 2.25 | 1.44; 3.53 | <.001 |

| III | 291 (26.0) | 136 (60.4) | 5.74 | 3.84; 8.58 | .000 | 6.01 | 4.02; 8.99 | <.001 |

| Surgical technique (reference: anterior resection) | ||||||||

| Abdominoperineal resection | 289 (25.8) | 81 (36.0) | 1.63 | 1.24; 2.14 | <.001 | 1.29 | 0.90; 1.84 | .116 |

Risk Factors for Mortality.

| No event | Event | Hazard ratio | Univariate | Hazard ratio | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=1011) | (n=332) | 95% CI | P | 95% CI | P | |||

| Age (10 years) | 6.49 (1.13) | 7.09 (1.10) | 1.56 | 1.40; 1.74 | <.001 | 1.52 | 1.36; 1.69 | <.001 |

| Gender (reference: female) | ||||||||

| Male | 644 (63.7) | 227 (69.9) | 1.20 | 0.95; 1.51 | .127 | 1.35 | 1.07; 1.70 | .012 |

| Tumour location (reference 7–12cm) | ||||||||

| 0-6cm | 437 (43.2) | 170 (51.2) | 1.32 | 1.07; 1.64 | .011 | 1.16 | 0.86; 1.56 | .329 |

| Neoadjuvant treatment (reference: no) | ||||||||

| Yes | 670 (66.3) | 189 (56.9) | 0.71 | 0.57; 0.89 | .002 | 0.82 | 0.66; 1.03 | .089 |

| TNM stage (reference: stage I) | ||||||||

| Complete response | 109 (10.8) | 7 (2.11) | 0.36 | 0.16; 0.77 | .009 | 0.40 | 0.18; 0.88 | .023 |

| II | 305 (30.2) | 95 (25.6) | 1.39 | 1.01; 1.91 | .044 | 1.39 | 1.00; 1.91 | .047 |

| III | 254 (25.1) | 173 (52.1) | 2.97 | 2.24; 3.94 | <.001 | 3.10 | 3.24; 4.12 | <.001 |

| Surgical technique (reference: anterior resection) | ||||||||

| Abdominoperineal resection | 246 (24.3) | 124 (37.3) | 1.69 | 1.35; 2.11 | <.001 | 1.37 | 1.00; 1.86 | .048 |

Tumour stages II and III had a negative impact on all the results. Complete pathological response increased overall survival. Furthermore, patient age and male sex had also an influence on overall survival.

DiscussionThis study shows that APR, in itself, has no influence on the occurrence of local recurrence or metastases, even though it deteriorates patient overall survival.

The main weakness of this study is related to the voluntary nature of data inclusion in the Rectal Cancer Project of the Spanish Association of Surgeons, especially when compared with Scandinavian countries’ registries,7,11 where the inclusion of data in the registry is compulsory, or with randomised studies.5,9,18 However, as already indicated,15 several initiatives have been taken to ensure data quality. With a view to avoiding inclusion biases, during the period of admission to the project, each hospital requesting admission was required to state the number of patients operated on annually over the past five years. After inclusion in the project, a 10% deviation in the annual casuistry was checked with the responsible surgeon. The database was updated continuously and the quality of data was reviewed monthly. When an inconsistency was detected (e.g. an MRI showing invasion of the visceral mesorectal fascia and a study of disease in which no circular resection margin invasion was observed), the registry requested the responsible person in the hospital to review the operative reports, pathology reports and photographs of specimens, if available. Patient follow-up included data on local recurrence, metastases, second tumours and survival/death. Follow-up information was sent monthly to the registry by the responsible surgeon in each hospital. The results were audited by the project coordinator and, in some instances, by health authorities.19

The participation of 38 hospitals may be considered as a study limitation due to the variability of practice.13,19 However, participating centres were included in a uniform teaching programme led by the director of the Norwegian Colorectal Cancer Project, and the results observed in the Rectal Cancer Project of the Spanish Association of Surgeons2,20 have replicated those of that project in two previous studies11,21 and in this one. Therefore, its multicentre nature reflects the external validity of the study.

Although some reference centres have shown that APR and AR outcomes are identical,8,10 the results obtained from randomised studies conducted to compare outcome variables based on the use of neoadjuvant treatments show that local recurrence and survival rates are worse with APR.5,22 These results against APR may be explained by the technical difficulties presented by low rectal cancer surgery, especially in patients with narrow pelvises or bulky tumours, and also by the idea that resection should not include the levator ani.

Only two previous articles7,11 developed with the same methodology used in this study evaluated the influence of APR itself as a predictor variable. The Norwegian Colorectal Cancer Project11 showed that APR did not lead to an increase in local recurrence rates although overall survival was worse. In another study conducted by the Stockholm Colorectal Cancer Study Group,7 it could not be demonstrated that APR was a predictor variable of any oncological outcome variables. In this sense, the results observed in the Rectal Cancer Project of the Spanish Association of Surgeons are similar to those of the Norwegian Colorectal Cancer Project.

It has been suggested that a more radical surgery called “Extralevator APR” may reduce the risk of invasion of the circumferential resection margin and of intraoperative perforation by achieving a standardisation of the technique.14 However, in a recent study edited within the framework of this project, it has not been verified that this technique has any advantage over conventional APR.23

To conclude, this study has not identified APR as a determining factor for local recurrence or metastases, but of decreased overall survival.

FundingThis project has been funded with the following research grants: FIS (Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria [Health Research Fund]) number: PI11/00010, and Department of Health, Government of Navarra: 20/11.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they do not to have any conflicts of interest.

Rectal Cancer Project of the Spanish Association of Surgeons Collaborator Group (years 2006–2009):

Virgen de la Arrixaca (Juan Luján), Bellvitge (Doménico Fraccalvieri, Sebastiano Biondo), Complejo Hospitalario de la Navarra [Navarra Hospital Complex] (Miguel Ángel Ciga), Clínico de Valencia [Clinical Hospital of Valencia] (Alejandro Espí), Josep Trueta (Antonio Codina), Sagunto (María D. Ruiz), Vall de Hebrón (Eloy Espín), La Fe (Rosana Palasí), Complejo Hospitalario Ourense [Ourense Hospital Complex] (Alberto Parajo), Germans Trias i Pujol (Ignasi Camps, Marta Piñol), Lluis Alcanyis (Vicent Viciano), Complejo Asistencial Burgos [Burgos Health Care Complex] (Evelio Alonso), Hospital del Mar [Del Mar Hospital] (Miguel Pera), Meixoeiro (Teresa García, Enrique Casal), Complejo Asistencial Salamanca [Salamanca Health Care Complex] (Jacinto García), Gregorio Marañón (Marcos Rodríguez), Torrecárdenas (Ángel Reina), General de Valencia [Valencia General Hospital] (José Roig), Txagorritxu (José Errasti), Donostia (José A. Múgica), Reina Sofía (José Gómez), Juan Ramón Jiménez (Ricardo Rada, Mónica Orelogio), Arnau de Vilanova de Valencia [Arnau de Vilanova Hospital of Valencia] (Natalia Uribe), General de Jerez [Jerez General Hospital] (Juan de Dios Franco), Arnau de Vilanova de Lleida [Arnau de Vilanova Hospital of Lleida] (José Enrique Sierra), Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Pilar Hernández), Clínico de Santiago de Compostela [Santiago de Compostela Clinical Hospital] (Jesús Paredes), Universitario de Jaén [Jaén University Hospital] (Gabriel Martínez), Clínico San Carlos [San Carlos Clinical Hospital] (Mauricio García), Cabueñes (Guillermo Carreño), General de Albacete [Albacete General Hospital] (Jesús Cifuentes), Miguel Servet (José Monzón), Xeral de Lugo [Xeral Hospital of Lugo] (Olga Maseda), Universitario de Fuenlabrada [Fuenlabrada University Hospital] (Daniel Huerga), Clínico y Provincial de Barcelona [Clinic and Provincial Hospital of Barcelona] (Luis Flores), Joan XXIII (Fernando Gris), Virgen de las Nieves (Inmaculada Segura, Pablo Palma), Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria (José G. Díaz).

Please cite this article as: Ciga Lozano MÁ, Codina Cazador A, Ortiz Hurtado H, en representación de los centros participantes en el Proyecto del Cáncer de Recto de la Asociación Española de Cirujanos. Resultados oncológicos según el tipo de resección en el tratamiento del cáncer de recto. Cir Esp. 2015;93:229–235.

Further information on the participants in the Rectal Cancer Project of the Spanish Association of Surgeons is available in Appendix A.