Carotid body tumours, glomus tumours or chemodectomas1 are the most common paragangliomas of the head and neck. They are rare, benign neoplasms, whose most frequent clinical presentation is a slow-growing, asymptomatic mass, which causes compressive symptoms in some cases1,2.

Clinical history, physical examination, and radiological diagnosis are the cornerstones of diagnosis and treatment1,3. Angiography is essential to study the vascular anatomy, particularly the “lyre sign”, typical of large tumours, which can distort the carotid bifurcation, extending the internal carotid artery (ICA) and external carotid artery (ECA)1,2.

Management of these tumours is technically challenging due to the size, location and hypervascularised state. They usually receive their blood supply through branches of the ECA2. Early surgical excision is considered the primary curative treatment option1,2. Advances in endovascular techniques have resulted in endovascular techniques to treat these tumours. Advances in endovascular techniques have enabled hybrid techniques, which involve embolisation of the tumour prior to surgical excision. These techniques are used in large tumours, with the aim of occluding the tumour’s nutrient vessels, reducing intraoperative bleeding and, therefore, morbidity and mortality4–7. Preoperative embolisation remains controversial, as it is not without risks, such as increased subsequent morbidity and inflammatory effects of the tumour, which may hinder accurate subadventitial dissection8. Transarterial embolization is the most commonly used route and is conditioned by the vascular anatomy of the afferent arteries, i.e., their small calibre, tortuosity, or the possibility of vasospasm during embolisation, making the procedure more complex and time-consuming5,6. Embolisation by direct puncture of the tumour is a simpler and less risky technique than transarterial embolisation, thus simplifying the surgical procedure and facilitating complete tumour resection by marking the limits of the tumour, with minimal complication rates5,6,9. Radiotherapeutic treatment is reserved for bilateral cases or in cases of excessive invasion10.

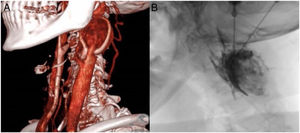

A 59-year-old female patient, active smoker as the only history of interest, was assessed by ENT for a left cervical mass of 2 months’ duration, associated with vertigo and tinnitus. On examination, she presented a left cervical mass, with vertical displacement and murmur. CT angiography showed a heterogeneous mass measuring 39 × 31 × 24 mm in its anteroposterior and transverse longitudinal axes, respectively, which enhanced intensely with contrast medium, located at the bifurcation of the left common carotid artery, between the ICA and ECA, with displacement of these arteries without obstructive signs (Fig. 1a). It was a Shamblin type II tumour.

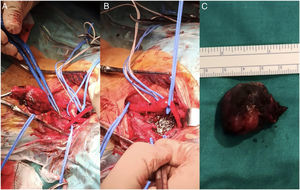

Elective surgery under general anaesthesia was decided, after prior embolisation of the tumour by the interventional radiology department. Embolisation of the paraganglioma was performed by direct percutaneous puncture with Onyx®, under radiological control, via the right femoral artery (Fig. 1b), with good subsequent control, where the absence of staining of the lesion was verified, and a repletion defect was visualised in the ECA due to a small amount of Onyx® inside it. After 3 days, surgical resection was performed transcervically, with a longitudinal incision typical of carotid endarterectomy, dissection by planes, with primary control using vessel loops of internal jugular vein, continuing with arterial dissection and subsequent control of common carotid artery, ECA, ICA, and superior thyroid artery. A tumour of approximately 3 cm was dissected without complications (Fig. 2). Closure was performed by anatomical planes.

The surgery was completed without incident, and the patient had no neurological focality after awakening from anaesthesia. On the first postoperative day, the patient reported mild dysphagia, and was therefore assessed by the ENT specialist, who ruled out disease, and she progressed with symptomatic improvement. She was discharged without complications.

The strategy used in the case described here avoided carotid clamping, thus preventing temporary cerebral ischaemia, and allowing safe surgical resection. A complication of embolisation was inadvertent migration of embolisation agent into the ECA, but it did not compromise vascularisation. However, the decision to perform pre-surgical embolisation must be made on a case-by-case basis, depending on the patient’s needs, the characteristics of the tumour, and always considering risks and benefits.

Conflict of interestsNone.