Hernias of the ureter are rare anomalies of the urinary system, with around 140 cases described in the literature. They can appear in the scrotum (indirect), inguinal area (indirect or femoral), gluteus (sciatic), thorax (Bochdalek hernia), or the space between the psoas muscle and the iliac vessels. Their presentation may be associated with other anomalies of the urinary tract, such as crossed renal ectopia.1–3 In kidney transplant recipients, hernia of the ureter should be ruled out as the cause of kidney failure,4,5 and it is necessary to consider them as possible findings in inguinal hernia repair surgery in order to avoid iatrogenic injuries.6

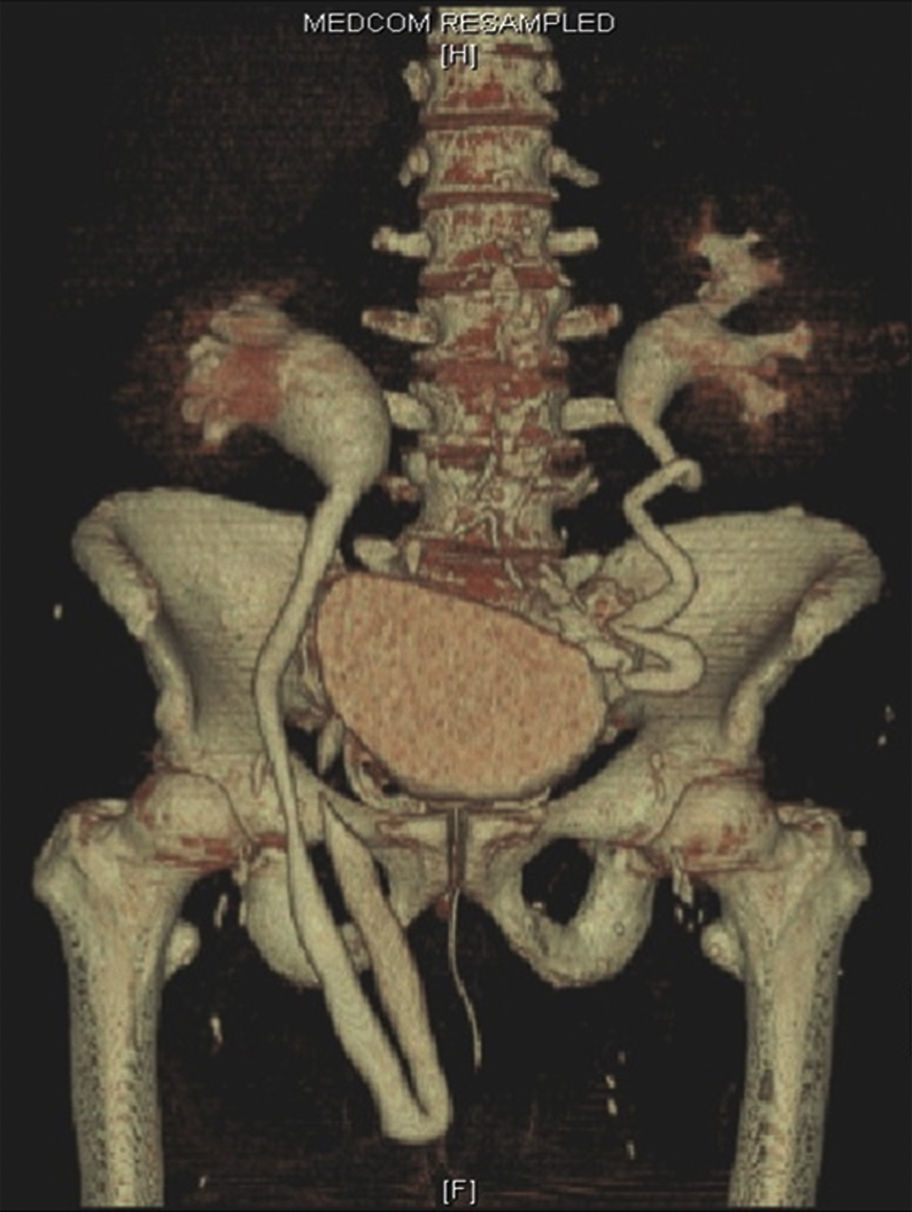

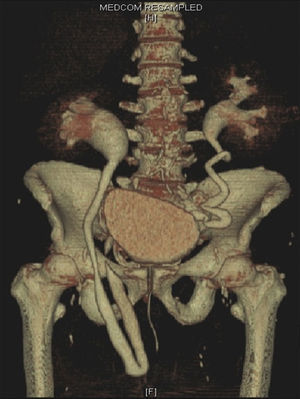

We report the case of a 68-year-old male whose history included arterial hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus and class II obesity (WHO). The patient was studied due to altered bowel movement frequency and mild rectal bleeding during the previous 2 months. Complete colonoscopy detected a mass that was 25cm from the anal margin; biopsy was positive for adenocarcinoma. Physical examination identified an uncomplicated irreducible bilateral inguinal hernia, which the patient had discovered 6 months earlier (Fig. 1).

The CT cancer extension study identified a right tubular structure that was hyperdense during the excretory phase and associated with ipsilateral hydronephrosis.7,8 Likewise, an important protrusion was observed in the right ureter through the deep inguinal orifice, following the pathway of an inguinoscrotal hernia. Although less evident, the left ureter also occupied its corresponding hernia orifice.

Intravenous urography is the diagnostic technique of choice. Three-dimensional reconstructions help determine the most appropriate surgical technique and approach to be used (Fig. 2).

Scheduled surgery involved the following steps:

- 1.

Laparotomy and sigmoidectomy with curative intent and colorectal anastomosis.

- 2.

Surgical fixation of the ureter to avoid postoperative rotations.

- 3.

Open preperitoneal approach: the bilateral hernioplasty was performed with the placement of a partially absorbable prosthesis, following the Rutkow–Robbins technique.

The postoperative period was uneventful and the patient has been evaluated at successive outpatient visits, showing no further symptoms.

Ureteroinguinal hernias are the most common form of ureteral hernias; their presentation can be paraperitoneal (80%) or extraperitoneal (20%). Our patient had a paraperitoneal hernia,9 which are associated with a peritoneal sac. The ureter is a retroperitoneal structure that is not within the sac, but instead forms part of its wall. A sliding hernia is caused by the posterior parietal peritoneum (comparable to the transverse fascia) exerting traction towards the inguinal canal. The extraperitoneal type involves the fatty tissue, but there is no true hernia sac.

The etiopathogenesis of this type of hernias could be related with anomalous development of the Wolff duct. During the testicular migration towards the scrotum, persisting genitourinary ligaments could exert traction over the ureter.10

In a study of 19 patients with ureteroinguinal and ureterofemoral hernias, Rocklin et al. described inguinal masses as generally the most common form of presentation during the fourth or fifth decades of life. Obstructive urinary and intestinal symptoms were present in 10 out of the 19 patients (52.6%). Furthermore, the ureteral hernias were associated with urinary tract anomalies in 46% of cases; the most common findings were crossed renal ectopia and renal ptosis.11,12 Sometimes, images of the urinary tract can reveal the “loop-the-loop” sign, which is pathognomonic of a ureteral hernia and represents the overlapping of the afferent and efferent branches of the ureter through the hernia sac, whose visualization improves with the patient in supine decubitus and the hernia partially reduced.10

Please cite this article as: Pareja-López Á, Sevilla-Cecilia C, Pey-Camps A, Dominguez-Tristancho JL, Muteb M. Hernia ureteroinguinal. Cir Esp. 2015;93:e89–e90.