This clinical case illustrates a rare and life-threatening presentation of celiac disease (CD), a celiac crisis with neurological symptoms. The diagnosis of celiac crisis should be included in the differential diagnosis of some types of diarrhea with serious metabolic disorders to prevent serious future complications. A large number of celiac patients remain undiagnosed for years, especially when the clinical form of the disease is atypical. They are exposed to risks of acute complications, as in the case reported here, or chronic complications, such as infertility, osteoporosis and lymphoma.

CASE REPORTA boy aged 4 years and 7 months was admitted to the emergency room with a chief complaint of unsteady walking that had started 10 h earlier. He felt drowsy and dizzy and was hypoactive. Following the neurological symptoms, he had a large volume of watery diarrhea. Before that, he was in good health, with no history of neurological or metabolic disease, fever or abdominal pain.

On admission, the child was dehydrated, but had normal temperature and blood pressure. His weight was 17 kg (25th percentile), and his height was 108 cm (50th percentile). The physical examination showed moderate muscle hypotrophy, scarce adiposity, abdominal distention and no visceromegaly. The neurological examination showed unsteady walking, dysarthria, hand dysmetria and isochoric light reagent pupils. He had irritability and self-aggressive behavior. Glasgow coma scale was 15. Drug screening tests were negative.

The child was born at term; birth weight was normal, and he was breastfed until 5 months of age. From the age of 2, he had sporadic diarrhea controlled with a low-fiber diet and lactose-free milk, and a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome was made. Enteropathogenic agents and blood in the stools were absent on all occasions. Serology tests for antigliadin (AGA) and antiendomysium antibodies (EMA) IgA and IgG were negative for CD at ages 2 and 4.

Laboratory test results showed hyponatremia (133 mEq/L), hypokalemia (3.1 mEq/L), hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis (pH 7.2; bicarbonate: 7 mmol/L; BE: –19.9). Serum chloride was 122 mEq/L, and lactate (<2 mmol/L) and glucose (85 mg/dL) levels were normal. Blood tests were normal. Liver and kidney functions were normal (TGO: 46 U/mL; TGP: 35 U/mL; urea: 10 mg/dL; creatinine: 0.3 mg/dL). Levels of serum iron, ferritin, cholesterol and albumin were extremely low. Stool analyses revealed no parasites, rare leukocytes and erythrocytes; cultures were negative and no Clostridium difficile toxins were detected. Radiographs showed global abdominal distension; cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT) scans and cerebrospinal fluid tests were normal. Both sleep and waking electroencephalograms were normal.

Similar episodes were observed four consecutive times at 1-week intervals. Before each admission, the child ingested large amounts of bread, cakes and pizza. In the first three hospital admissions, his neurological symptoms faded within 2 days, but the hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis persisted without any evident cause. He had received intravenous hydration and was placed on a low-fiber and hypoallergenic diet without gluten restriction. The need for bicarbonate and potassium chlorate was high, so it was suggested that the loss of potassium and bicarbonate was probably associated with fecal loss because his kidney function was normal. During his fourth admission, a complete investigation for malabsorption was carried out.

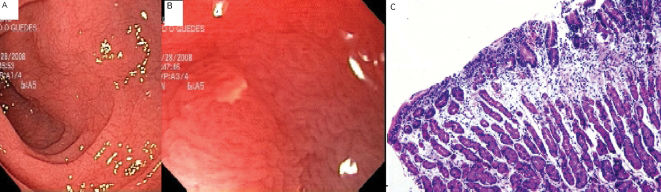

Fecal analysis revealed an increased loss of fats. Serum IgA EMA and IgA anti-tissue transglutaminase antibody (anti-tTG) was reagent, over 100 U/mL. CD was suspected. The mucosa magnified by endoscope showed microhemorrhage, reduction in duodenal folds and multiple erosions (Figure 1A and B). Histological examination showed partial and total villous atrophy, intraepithelial lymphocytes and increased length crypts (Marsh 3C) (Figure 1C).

After the introduction of a gluten-free diet, the child improved progressively, and a supplement of folic acid, iron and calcium was introduced.

DISCUSSIONThis is a rare presentation of celiac crisis, with acute ataxia in a child whose serological blood tests were negative for CD.

Celiac crisis is the most acute form of CD and has not been described in Brazil before. It is characterized by explosive diarrhea, dehydration and severe electrolytic abnormalities, as was observed in this case.1,2 It can be fatal if left untreated.3 Celiac crisis may complicate the diagnosis of CD, or it may be the initial symptom of this disease, as in our patient. Descriptions of neurological disturbances in CD have increased, but no report has included celiac crisis until now. Gupta et al. first described a celiac crisis in a 30-year-old woman with acute quadriparesis and attributed the neurological disturbances to refractory severe hypokalemia.4 Our patient had presented with cerebellar ataxia before the onset of diarrhea and metabolic abnormalities in four hospital admissions, which confirmed the neurological involvement during celiac crisis.

The physiopathology of neurological disturbances in cases of CD is unknown, but immunological, nutritional, toxic and metabolic mechanisms have been suggested. Neurological disturbances occur in 8–10% of adults with CD and are less frequent in children.5 Ataxia is the most frequent neurological symptom, followed by myoclonias, neuropathies and dementia. Some authors believe that there is a positive correlation between gluten sensitivity and cerebellar disease because of the presence of AGA in patients with neurological symptoms of unknown etiology.6 AGA may have a neurotoxic effect in CD when they cross the intestinal mucosa during enteral infections, in case of a “leaky gut”, and they could have a cross-reaction with Purkinje cells.7 The neurotoxic effects caused by the increased ingestion of gluten, in conjunction with the metabolic disturbances caused by diarrhea, may be the cause of the cerebellar ataxia, irritability, drowsiness and muscle weakness seen in our patient. The low serum potassium levels resulting from excessive loss in feces worsened the weakness and led to uncoordinated movements, which may explain the high potassium demand. Vitamin E and vitamin B12 deficiencies, due to chronic malabsorption, may also cause spine cerebellar degeneration and peripheral neuropathies.5

The abrupt increase in gluten ingestion and the recovery from ataxia and diarrhea by reducing gluten ingestion may be strongly associated with dosage. The influence of the amount of gluten on CD is controversial, and no studies have investigated this in cases of celiac crisis. Fasano et al. showed that the gluten-induced upregulation of zonulin, an intestinal peptide involved in the regulation of tight junctions, is responsible, at least in part, for the aberrant increase in gut permeability that is characteristic of the early phase of CD, and it reaches higher levels in the acute phase of CD.8 Also, zonulin seems to facilitate the passage of macromolecules through enterocytes and is responsible for the increased incidence of autoimmune illnesses in untreated CD patients. The excessive amount of gluten ingested by our patient might have led to an increase in intestinal permeability, according to this mechanism. Therefore, under normal conditions, the juxtaposed enterocytes would limit the passage of macromolecules (including gluten peptides) and avoid the crisis. This explains the child's recovery after the reduction in gluten ingestion at the hospital, without any specific neurological treatment; metabolic acidosis, however, persisted.

From the age of 2, the patient had a satisfactory nutritional evolution, together with a state of mild malabsorption. Breastfeeding might have delayed the clinical signs and symptoms of CD; or the patient might have become tolerant to low doses of gluten via intrinsic factors; or both.9 The exposure to gluten before the third month, or its ingestion in large amounts during weaning, may trigger CD in children with a genetic predisposition. Our patient's low exposure to gluten since weaning might not have reached the level necessary to compromise his intestinal mucosa and affect his nutritional state. Later, a large amount of gluten led to uncontrollable diarrhea, and hypoalbuminemia created conditions for low tolerance to fluid loss, metabolic acidosis and hypokalemia, all characteristics of celiac crisis.4

The development of serological markers for CD screening has facilitated its early diagnosis in risk populations. The sensitivity of serological EMA and anti-tTG antibodies is greater than 90%, and these test markers are the best diagnostic options for CD. Our patient had only AGA and EMA antibodies, which are not sufficient to diagnose CD because they are not very accurate in cases of partial villous atrophy.10