The aim of the present work is to analyze the differences and similarities between the elements of a conventional autopsy and images obtained from postmortem computed tomography in a case of a homicide stab wound.

METHOD:Comparison between the findings of different methods: autopsy and postmortem computed tomography.

RESULTS:In some aspects, autopsy is still superior to imaging, especially in relation to external examination and the description of lesion vitality. However, the findings of gas embolism, pneumothorax and pulmonary emphysema and the relationship between the internal path of the instrument of aggression and the entry wound are better demonstrated by postmortem computed tomography.

CONCLUSIONS:Although multislice computed tomography has greater accuracy than autopsy, we believe that the conventional autopsy method is fundamental for providing evidence in criminal investigations.

A forensic autopsy is traditionally a tool used to achieve justice because the findings may serve as evidence for investigating the circumstances of death 1,2. Over the last century, the methods of conventional autopsy have undergone few changes; autopsy still involves external examination and evisceration, organ dissection for the macroscopic identification of diseases and injuries and the collection of samples for histopathology 3. However, there have been advances in toxicology exams and DNA analysis. Recently, the adoption of imaging techniques such as multislice computed tomography (MSCT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have established the virtual autopsy as a method of analysis to facilitate autopsy procedures 4,5.

Postmortem computed tomography (PMCT) has been used around the world for more than a decade 4,5. However, Brazilian researchers only began routine studies with an MSCT scanner exclusively for postmortem analysis in 2013, after developing comprehensive infra-structure in a large autopsy center. In the present study, we compare the results of a virtual autopsy performed with PMCT to those obtained by conventional forensic autopsy in a stabbing murder case.

METHODSA 42-year-old male was stabbed in the chest during an argument. An ambulance was called, but the physician arrived after the victim died. All the usual procedures were followed for cases of murder. Prior to the conventional autopsy, we performed a whole-body PMCT approximately four hours after the time of death. The conventional autopsy procedure was performed soon after the PMCT examination at the Medical Legal Institute.

The body was scanned in a dedicated post-mortem 16-slice computed tomography (CT) system (multislice SOMATOM syngo CT 2012E ® Emotion - Siemens, Germany) installed in the main building of the University of São Paulo School of Medicine, with the following parameters: 1.2 mm collimation, 130 kV, 122 mA average, pitch 0.55 and rotation time of 1 s. An acquisition time of 42.1 s for body volume imaging (including lung) and of 29.5 s for lung imaging was used and the images were reconstructed with a 1.5-mm slice thickness, a 0.7-mm gap and a smooth filter.

The image analysis was performed by two radiologists with more than 10 years of professional experience who were not present when the images were collected by the PMCT and who did not know about the results of the conventional autopsy. The images were analyzed with the aid of the software program OsiriX© (v. 10.7 - Pixmeo, Sari - Switzerland) using multiplanar reconstructions (MPRs), maximum intensity projection (MIP), minimum intensity projection (MinIP) and volume-rendering (VR) tools. The window settings were controlled dynamically according to the needs of interpretation and the images were viewed independently on a digital LCD monitor with a contrast ratio of up to 10,000:1.

The forensic autopsy was performed by a conventional medical examiner with over 10 years of experience who was not aware of the results obtained with the PMCT.

All the analyses performed with the PMCT were performed after obtaining permission from the responsible ethical committee and family consent was not required by the committee.

RESULTSPostmortem Computed Tomography (PMCT)Some of the tomography findings were consistent with the findings from the conventional autopsy. However, in addition to the lesions detected by the conventional examination, some findings by PMCT provided additional information.

In the chest region, we noted subcutaneous emphysema around the external injuries, and 2 regions had greater extension into the subcutaneous tissue of the thoracic region (left lateral and axillary area and the anterior thoracic region, Figure1).

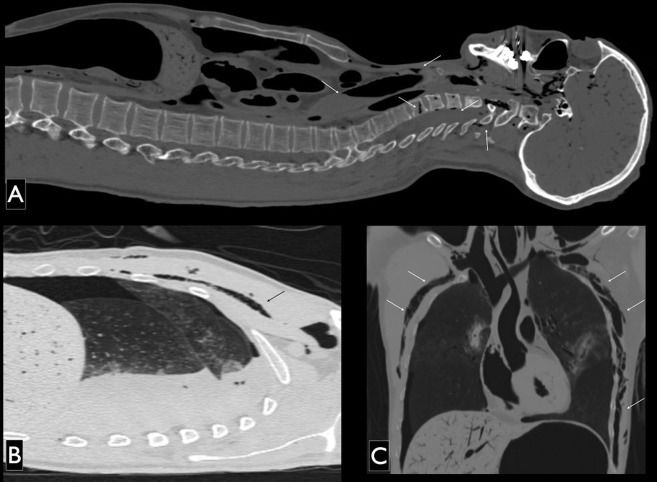

PMCT images, sagittal multiplanar reconstruction (A and B) and coronal (C) pulmonary window settings. The following structures are labeled with arrows pointing to the gas contents: A) dural venous plexus, central vein of the vertebral body of C6 and other veins in the cervical vertebral bodies (note the dense liquid inside the trachea); B) subcutaneous emphysema in the soft tissues of the right anterior thorax; C) and more extensive subcutaneous emphysema in the left lateral aspect of the thorax.

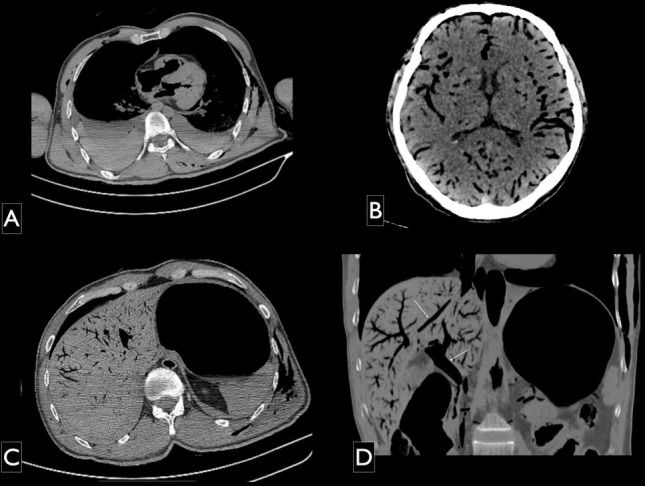

We also noted gas in the internal organs, distributed intravascularly, notably in the brain, heart and liver. Bilateral fluid in the pleural space with the highest volume in the right side was also noted and a higher density was found in the posterior regions, indicating probable hematic components (Figure2).

PMCT images, multiplanar reconstruction axial (A and B) and coronal (C) pulmonary window. Findings in parenchymal organs: A) fluid-fluid level with higher protein decanted in the bilateral pleural space, with a larger volume on the right side; B) gas distributed in intracranial arterial and venous compartments; C) and D) intrahepatic gas in the systemic and portal venous drainage systems (arrows).

A massive number of gas embolisms were found in the vascular structures, especially in the arterial system in the aortic arch, great vessels (trunk brachiobasilic-cephalic subclavian arteries, common carotid, internal and external carotid, right brachial artery, abdominal aorta, iliac and common femoral arteries), the large veins (internal jugular, subclavian, superior and inferior vena cava and portal system), veins in the cervical and thoracic vertebral bodies and the dural plexuses.

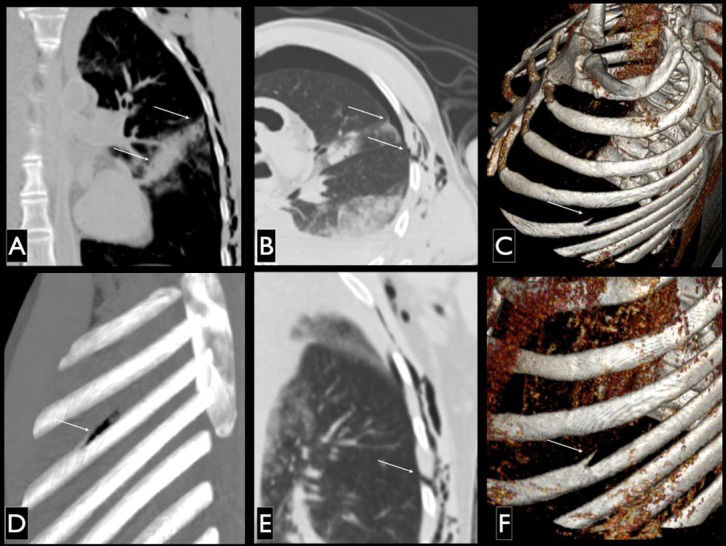

The PMCT images allowed the reconstruction of the trajectory of the cutting instrument (blade) used for aggression, coinciding with the description produced by the conventional autopsy. A wound in the skin was clearly visible in the PMCT volume-rendered images above the anterior part of the third rib (see Discussion) at approximately 3.5 cm from the right nipple in the medial and upper aspects of the thorax; however, the lesion in the left axillary region was more difficult to detect using this method. Nevertheless, the intrathoracic lesions, emphysema volume, skin irregularities and increased density indicated the presence of at least one penetrating injury on this topography. The lesion in the left scapular region was not detected.

The main findings in the right thoracic region were the entry wound and the hyperdensity path in the pulmonary parenchyma, with air gaps in the upper and middle lung lobes that almost coincided (see further discussion) with the opening in the skin up to the region of the left atrium in a linear pathway, with opacification of the right bronchus source. Although more difficult to detect, the entrance hole in the left armpit and the hyperdensity path in the left hemithorax, with an upper lobe oblique trajectory reaching close to the cardiac area were also noted. The key finding used to determine the entry wound was the detachment of part of the superior cortex on the upper edge of the fifth rib on the left; this most likely corresponds to the point where the blade tip penetrated and injured the bone. This finding (the object entry point in the skin below the lesion topography) and intrathoracic rib injuries are discussed below. These findings are detailed in Figure3.

PMCT images, multiplanar reconstruction coronal (A), coronal minimum intensity projection (B) and axial (C) pulmonary window; three-dimensional reconstruction technique for maximum intensity projection (D) and volume rendering showing bony structures in the left oblique lateral view. Note the lesion wound in the skin and the lung injury (A and B), the details of the lesion in the fifth left rib (in C, D and F) and the distance between the lateral aspect of the path of lung injuries and skin lesions and rib while the arm is positioned down (detail B).

The accuracy of the element depiction described by both autopsy methods is summarized in the following table (Table1), with the number of crosses indicating detection efficacy.

- Comparison between the autopsy methods.

| Post-mortem computed tomography | Conventional Autopsy | |

|---|---|---|

| External lesions | + | + + |

| Right hemothorax | + + | + |

| Left hemothorax | + + | + |

| Pneumothorax | + + | - |

| Lung lesions | + | + |

| Pulmonary hilar injury | + | + + |

| Subcutaneous emphysema | + + | - |

| Air embolism | + + | - |

| Lesion pathway | + + | + |

| Cause of death | + + | + |

PMCT: post-mortem computed tomography; +: detected element, -: non-detected element.

After the image analysis, we came to the conclusion that death occurred by acute internal hemorrhage associated with traumatic air embolism.

Conventional AutopsyThe external lesions were described in greater detail by the conventional autopsy: a stab wound measuring 2 cm in the right pectoral region close to the nipple; an incised wound measuring 2.5 cm in the left axillary region; and a stab wound of 2.5 cm in the left scapular region. The right thoracic cavity contained 1.8 liters of blood (hemothorax); the left side contained 0.7 liters. On the left side, we observed transfixing lesions in the upper right and hilar regions of the right lung and the upper lobe of the left lung, which showed localized parenchymal hemorrhage. The conventional autopsy determined that the cause of death was due to traumatic acute internal hemorrhage.

DISCUSSIONAutopsy examinations of knife assault victims are part of the daily practice of Brazilian coroners because the numbers of homicides in the major urban centers of the country are among the highest in the Americas, even higher than countries at war 6.

The present case shows that imaging in the autopsy room is valuable for bringing criminals to justice because imaging increases the precision of the elements that are being investigated as evidence, thereby allowing extensive documentation in cases of trauma 7-10.

Although an examination of the soft tissues was performed by PMCT, regarding external injuries, conventional autopsy still provides better results when compared with PMCT. Only two of the three lesions described in the autopsy were detected by conventional imaging. Moreover, only the first method detailed the format and vitality of the edges of the lesions, consistent with related studies 11,12. The left scapular lesion was not detected by PMCT. Nevertheless, in a post hoc analysis, suspicion about the existence of this lesion according to the external elements (presence of higher density in the tissue surrounding the lesion referred to) would be raised, but this finding did not initially catch the attention of the radiologists who analyzed the images. We believe this was due to the supine position used for imaging, which compresses the tissue and prevents the documentation of three-dimensional images of the surface. We also have to consider that a visual inspection would be sufficient to detect these lesions in the CT room, in the same manner as a conventional autopsy. Because this procedure is noninvasive, it can and should be performed in all cases.

The path of the lesions in the lungs was similarly described by the two methods. However, conventional autopsy is more time consuming than PMCT because a description must be made prior to each planned dissection. Moreover, the instrument trajectory is destroyed after conventional autopsy; thus, evidence is not preserved and documentation reproducible in the Courts is not provided. Therefore, some authors have considered PMCT to be superior to conventional autopsy 7.

The vascular lesions found in the internal examination were also better described by postmortem CT, as mentioned in a recent study 11. However, as postmortem angiography was not performed, this conclusion is based strictly on the analysis using non-contrast PMCT.

The lesions in the lung parenchyma and hemothorax were described in a similar manner by both methods. According to previous analyses, the difference between conventional and postmortem CT descriptions of such elements is less than 20%, which is consistent with the findings in our case 13.

The subcutaneous emphysema detected by PMCT is rarely described by coroners, even experienced ones. Indeed, when opening cavities, the chance of detecting such a change is close to zero. Thus, for this particular aspect, PMCT imaging is superior to conventional autopsy 14,15. In particular, the detection of the pneumothorax by PMCT is consistent with the evidence from other authors showing that this finding may be underdiagnosed using conventional autopsy, whereas it can be quite evident on PMCT 16.

The superiority of PMCT was also noted with regard to the description of the air embolism, an element that was lost in the conventional autopsy. The presence of air embolism in the large veins can be explained by the discontinuation of the vessel walls, which allowed the external air to enter the vessels while the victim was still alive. The greater precision of the imaging in relation to this change has been demonstrated previously by several authors 11,13,15. Thus, although PMCT is not able to detect vital reactions at the edges of the lesion, in this case, it showed that the lesions occurred during life because subcutaneous emphysema and gas embolism were found, which could be considered signs of vitality and no cardiopulmonary resuscitation maneuvers were performed.

Other authors have also noted the presence of gas embolism detected by PMCT. A study conducted on 27 Israeli soldiers (victims of military trauma) reported 2 cases with extensive findings of gas embolism, similar to the case described here. These authors state that the etiology and interpretation of the findings are still questionable because the mechanism resulting in these images had not been fully elucidated; they stated that it was not possible to conclude whether the gas was allowed into the circulation post mortem or while the victims were still alive 17. Another study conducted in Japan shows that this finding may be associated with resuscitation maneuvers and the authors guardedly did not state the cause of the presence of gas in the arterial circulation and parenchymal organs 18. The finding of intrahepatic gas has also been described in autopsies and is even more commonly associated with open trauma. Particularly when using CT after death, intrahepatic gas is found in up to 59% of cases with open injuries, including pulmonary barotrauma related to artificial respiration 19. According to these authors, this finding is not unusual in cases of simple putrefaction and it is only observed when there are macroscopic signs of putrefaction.

Regarding the mechanism of death, PMCT detected massive gas embolisms in vital organs, such as the brain and liver, indicating that gas embolism is directly related to the cause of death. An alternate source for this finding is unlikely because of the following: 1) the time of death until the image was produced was less than 6 hours; 2) no resuscitation was performed; and 3) the individual did not receive artificial ventilation. Thus, we believe that this is a key point in our case. The conventional autopsy identified only the internal acute hemorrhage due to the traumatic hemothorax formed mainly by the injured hilum as the cause of death because it was not able to detect the air embolism. However, the discrepancy between the tests cannot be considered an error because the detection of gas embolisms is extremely difficult for a medical examiner. In fact, the non-description of gas embolisms is very common 11.

The authors believe that the two methods – conventional autopsy and PMCT – are still complementary because the analyses did not prove which method is superior. However, we are confident that a new field is coming into existence worldwide. Because such studies demand professionals with the capacity to understand pathology, forensic medicine and radiology simultaneously, a new specialty is imminent.

Although PMCT shows some findings with greater accuracy than autopsy, we believe that the conventional method in the present case is still fundamental for providing evidence for criminal investigations, especially regarding external examination. However, the findings of gas embolism, pneumothorax pulmonary emphysema and the relationship between the internal path of the instrument of aggression and the entry wound were better demonstrated by PMCT. Thus, we believe that further studies should be designed to acknowledge the pros and cons of each approach and to pave the way for fully integrated procedures.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThe authors wish to thank the Instituto Médico Legal of São Paulo and Serviço de Verificação de Óbitos de São Paulo for collaborating on the present study and the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo – FAPESP for financial support.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONSThe authorship contribution for the present article occurred as follows. Silva LF, Saldiva PH and Pasqualucci CA conceived and designed the study and final approved the final version of the manuscript. Kay FU and Amaro Jr E were responsible for the postmortem computed tomography study. Ferro AC was responsible for the conventional autopsy. Zerbini T was responsible for the manuscript drafting.

No potential conflict of interest was reported.