Infections are one of the major causes of mortality in the first year after organ transplantation (1). Bacterial infection is the most frequent type of infection. Chang et al. found that 82% of fever episodes in the first two years after liver transplantation were nosocomial infections; bacterial infections were found in 62% of cases (2).

Approximately half of bacterial infections occur within two weeks after liver transplantation. The following risk factors related to these infections were identified: 1. Immunosuppression; 2. Recipient characteristics; 3. Procedural characteristics; and 4. Donor characteristics. Organ transplant donors are exposed to several situations that are associated with a risk of infection; therefore, donors have the potential to transmit microorganisms to organ transplantation recipients (1).

Transmission through the graft is well described for some infections, such as toxoplasmosis in heart transplantation and mycobacteriosis in liver, kidney and lung transplantation (3,4). Virus transmission is also well documented. Donors are typically screened for the following viruses: human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B and C viruses, EBV, CMV and human T-cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV). The transmission of HTLV in this manner has not been documented but is highly probable (5).

Bacteria and fungi can be transferred to the allograft by contamination during the recovery, preservation or handling of the organ or at the time of transplantation. Contamination from a donor infection is most likely the most critical because a large inoculum of microorganisms can be transmitted. Information regarding nosocomial infection (fungal and bacterial) retrieved from donor organs, however, is limited. The donor-to-host transmission of bacterial infection has been documented in some case reports and large series. In Canada, one donor transmitted methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) to two kidney recipients and one cornea recipient (6). Organ contamination by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, S. aureus and Candida species at the time of harvesting has been reported in kidney transplantation. The agents were isolated from donor fluids and graft preservation fluid, and the recipients developed serious infections (7).

Several studies have reported a low risk of recipient infection when the donor had bacteremia and both donor and recipient were treated. Four studies analyzed the outcome of solid organ transplantation when there was documented bacteremia in the donor (7–10). Lumbreras et al. identified bacteremias in 5% of liver and heart donors (10). The most common agent was S. aureus. The majority of recipients received treatment for agents isolated in the donor blood cultures; there was no negative impact on the survival of the graft or of the patient. Freeman et al. analyzed the outcome of 212 patients who received organs from 95 donors with bacteremia (11). Surprisingly, none of the recipients developed infections caused by the agents found in the donors.

The organs of donors with bacterial meningitis can be transplanted without increasing the risk of infection in recipients. Lopez-Navidad et al. (12) reported on 16 recipients who received organs from donors diagnosed with meningitis. All of the recipients were treated post-operatively for the same microorganism as isolated from the donors, and no patient developed an infection. In another series, 33 liver transplants from donors with meningitis were described; there were no cases of transmission to a recipient. In this study, both donors and recipients had been treated for the isolated agents (13). These data suggest that it is safe to transplant organs from donors with bacterial infection if the donors do not have signs of sepsis, the causative agent of the infection is identified, and the recipients receive the appropriate treatment immediately post-transplantation. However, infections that are not correctly identified may be transmitted. Hypothetically, the risk is higher for microorganisms resistant to the prophylaxis regimen routinely used in transplant care units.

Approximately 5% of donors have positive blood cultures at the time of transplantation, but some studies report this figure to be as high as 20% (11,14). The international consensus is that systematic blood culturing should be performed for all transplanted organs. There is no current recommendation in Brazil.

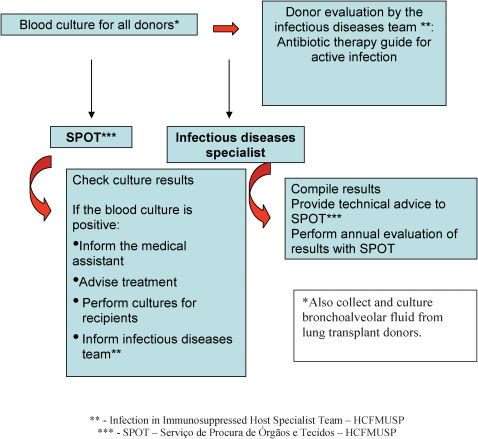

Considering the risks for bacterial infection and the potential benefits of knowing the microbiological status of the donor organ, we propose that systematic cultures of donor materials should be performed. Blood cultures should be performed for all organ transplantations and bronchoalveolar fluid culture should be performed in all cases of lung transplantation (Figure 1).

The primary goal of standardization is to provide important infectious and microbiological information (Figure 1), which could be helpful in determining the appropriate prophylactic and therapeutic measures for use in transplant recipients.

APPENDIXAVALIAÇÃO DE INFECÇÕES BACTERIANAS EM DOADORES DE ÓRGÃOSAs infecções constituem-se em uma das principais causas de morbi-mortalidade no primeiro ano após o transplante de órgãos (1), sendo mais frequentes as infecções bacterianas. Chang et al. demonstraram que 82% dos episódios de febre em dois anos de seguimento após transplante de fígado são de origem hospitalar, e desses 62% são de origem bacteriana (2).

Cerca de metade das infecções bacterianas ocorre em até duas semanas após o transplante. Alguns fatores de risco foram identificados como determinantes na incidência dessas infecções: 1. Fatores relacionados à imunossupressão; 2. Fatores relacionados ao receptor; 3. Fatores relacionados ao procedimento, e 4. Fatores relacionados ao doador. Devido às condições clínicas dos doadores, estes estão submetidos a vários fatores de risco para infecções nosocomiais, com potencial de transmissão para o receptor (1).

Algumas infecções já foram bem definidas como passíveis de serem adquiridas do enxerto, como toxoplasmose em transplantados de coração e mico bacteriose em transplantados de rim, fígado e pulmão (3,4). A transmissão de infecções por vírus também é bem documentada. Pesquisam-se os seguintes vírus, rotineiramente, no doador: vírus da imunodeficiência humana (HIV), vírus das hepatites B e C, EBV, CMV e vírus humano linfotrópico de células T (HTLV), este último sem transmissão documentada, porém altamente provável (5).

Poucas informações existem, entretanto, sobre a possibilidade de transmissão de agentes de infecção hospitalar (bactérias e fungos) através do enxerto. No Canadá, foi descrita a transmissão de Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) resistente a oxacilina de um doador para dois receptores de rim e um de córnea (6). Descreveu-se, em transplante de rim, contaminação do enxerto durante a retirada e preservação do órgão. Os agentes identificados foram Pseudomonas aeruginosa, S. aureus e fungos isolados de fluidos do doador ou da solução de preservação, e responsáveis por graves infecções nos receptores (7).

Alguns estudos mostram que as bacteremias no doador, quando identificadas e tratadas, tanto no receptor quanto no doador, não representam risco de infecção para o receptor. Quatro estudos avaliam a evolução de transplantados que receberam órgãos de doadores com bacteremia documentada (7–10). Lumbreras et al. identificaram 5% de bacteremias em doadores de fígado e coração (10). O principal agente identificado foi S. aureus. A maioria dos receptores recebeu tratamento para o microorganismo identificado na hemocultura do doador. Não houve diminuição na sobrevida do enxerto ou do paciente. Freeman et al. avaliaram a evolução de 212 pacientes que receberam órgãos de 95 doadores com bacteremia (11). A maioria recebeu antibioticoprofilaxia ativa contra essas bactérias, e nenhum receptor evoluiu com infecção pelo mesmo agente do doador.

Doadores com meningite bacteriana também foram utilizados sem que isto acarretasse em maior risco de sepse nos receptores. Lopez-Navidad et al. descreveram 16 transplantados que receberam órgãos de doadores com meningite bacteriana (12). Todos receberam tratamento no pós-operatório para os agentes isolados no doador, e nenhum paciente evoluiu com infecção por esses agentes. Outra série de 33 transplantes de fígado com doadores com meningite foi descrita sem nenhum caso de infecção nos receptores; neste estudo tanto os doadores quanto os receptores receberam tratamento para o agente isolado (13).

Esses dados sugerem que, aparentemente, é seguro receber órgãos de doadores com infecção bacteriana que não apresentem sepse clínica, desde que essas infecções tenham agente etiológico identificado no doador e sejam tratadas adequadamente no pós-operatório imediato. Porém, infecções que não foram diagnosticadas adequadamente podem ser transmitidas. Teoricamente este risco é maior para microorganismos não sensíveis aos antibióticos comumente usados na profilaxia do transplante.

Em média, 5% dos doadores apresentam hemocultura positiva no momento do transplante, porém em algumas séries a positividade das hemoculturas chega a 23% (11,14). Alguns consensos internacionais recomendam a coleta de hemocultura de todos os doadores de órgãos. No Brasil não há recomendação específica.

Considerando os riscos da aquisição de infecção bacteriana e o potencial benefício de se obter dados microbiológicos dos doadores de órgãos, propomos uma sistematização de coleta de culturas destes doadores (Figure 1). Sugere-se incluir basicamente a coleta de hemoculturas, exceto para os casos de transplante de pulmão, em que a identificação de colonização de vias aéreas também tem utilidade demonstrada. O objetivo primário desta padronização é proporcionar informação microbiológica e infecciosa (Figure 1) importante para auxiliar na adoção de medidas profiláticas e terapêuticas no paciente transplantado.

We would like to express our gratitude to Prof. José Otavio Costa Auler Jr, Prof. Tarcísio Eloi Pessoa de Barros Filho and Prof. Eloísa Bonfá for their support as Clinical Directors of Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo.