Fever of unknown origin (FUO), defined as a temperature higher than 38.3°C on several occasions and lasting longer than three weeks that is associated with a diagnosis that remains uncertain after one week of investigation (1), is a frequent condition in the infectious diseases specialty clinic. The condition is often associated with extensive diagnostic procedures and, not rarely, frustration for both the patient and the physician. An evidence-based approach has been used to group the causes of FUO (2) into four general categories: infectious, rheumatic/inflammatory, neoplastic, and miscellaneous disorders (3). Infectious diseases such as endocarditis, intra-abdominal abscesses, and tuberculosis, as well as inflammatory conditions such as temporal arteritis, adult's Still disease, and late-onset rheumatoid arthritis, are commonly identified causes of FUO (3). However, unexpected and rare causes are sometimes diagnosed, as reported below in a case of sclerosing mesenteritis.

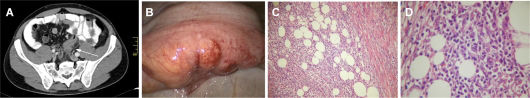

CASE DESCRIPTIONA 44-year-old, previously healthy man was referred to the infectious disease specialist for the investigation of fever that had occurred in the previous 10 days and fatigue that had been present for the previous 30 days. He reported being chronically constipated, which had worsened over the previous 30 days. The daily fever was the main complaint and arose at any time of the day without chills or notable sweats; no weight loss was reported. The physical examination was unremarkable, and the initial laboratory findings revealed only a low positive protein levels as determined by urinalysis and slight increases in the levels of C-reactive protein and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, with a normal complete blood count. Tests for mononucleosis-like agents were negative for active infections. The patient was hospitalized for additional exams and evaluation. Fever (38-38.5°C) was confirmed, but it disappeared right after the introduction of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication (naproxen). Echocardiography, blood cultures, an eye fundoscopic examination, and a colonoscopy were all unremarkable. The patient was then submitted to abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) scans, which revealed a mural thickness in the sigmoid colon with nodular densities in adjacent adipose tissue (Figure 1A). Large numbers of lymph nodes up to 1.0 cm in diameter were observed near the inferior mesenteric vessels. An intestinal lymphoma was initially suspected, and the patient was submitted to abdominal laparoscopic surgery with rectosigmoidectomy and lymph node resection. The intraoperative aspect was of a chronic inflammatory lesion affecting the entire mural thickness and adjacent tissues in addition to moderate dilation of the proximal colon (Figure 1B). After hematoxylin-eosin staining, the histopathologic exam revealed extensive lymphoplasmocytic inflammatory infiltrate with collagenic deposition involving the mesenteric adipocytes (Figures 1C and 1D). Staining for IgG4 was negative in the inflamed tissue.

A: Abdominal and pelvic CT scan showing mural thickening of the sigmoid colon with densification of the adjacent mesenteric fat (white arrow) and an increased number of lymph nodes up to 1.0 cm in diameter near the inferior mesenteric vessels; B: Surgical photography showing the inflamed sigmoid; C and D: microscopic exam after hematoxylin-eosin staining showing an extensive lymphoplasmocytic inflammatory infiltrate with collagenic deposition involving the mesenteric adipocytes at 100x (C) and 400x (D) magnifications.

After the surgical procedure, clinical recovery was adequate, and there was no rebound of fever or weakness after discontinuation of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. At a follow-up visit eight months later, the patient remained asymptomatic and no longer complained of intestinal bowel symptoms or fever.

DISCUSSIONSclerosing mesenteritis is a rare idiopathic condition characterized by a non-neoplastic inflammatory process in the mesenteric fat (4). Men are more commonly affected than women, and the incidence increases in middle-aged and older adults (5). The clinical presentation and radiological findings are nonspecific, which renders the condition a diagnostic challenge for surgeons and internists.

Granulomatous and neoplastic diseases are part of the differential diagnosis for sclerosing mesenteritis on clinical and radiological grounds (6). Therefore, histopathology remains the main diagnostic tool (7). The histological findings are fibrosis, myofibroblasts, and inflammatory cell infiltration of the fatty tissue with degeneration or fat necrosis; aggregations of lipid-laden foamy macrophages are also present (4,8). The process can be predominantly inflammatory with fat tissue inflammation and necrosis (mesenteric panniculitis) or predominantly fibrotic, which leads to retractile mesenteritis (7–9).

Sclerosing mesenteritis is sometimes observed in association with a multisystem clinical syndrome affecting the pancreas, biliary tract, liver, kidneys, and lungs; this condition has been described as “IgG4-related systemic sclerosing disease”, and one of the most common histopathological features is the presence of IgG4+ plasma cells within involved tissues (10). However, cases of sclerosing mesenteritis have also been described in the absence of other sites of involvement.

The likely causal relationship of the disease and FUO in this case is supported by the lack of any other diagnosis, the confirmatory histological findings of sclerosing mesenteritis, and the remission of fever with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and the surgical removal of involved tissue. At a follow-up visit, the patient remained asymptomatic, suggesting that the local process was the only cause of FUO. Case reports of sclerosing mesenteritis as a cause of FUO are rare, and we were able to identify only seven cases after a thorough review of the medical literature (Table 1).

Case reports of sclerosing mesenteritis as a cause of FUO.

| Author, year | Age (years), gender | Days with fever | Associated symptoms | Diagnostic criteria | Tissue IgG4 | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Otto et al., 199111 | 76, M | 14 | Abdominal pain, weight loss, shivering | CT and laparoscopic biopsy | Not available | Fever resolved under corticosteroid therapy, and the patient remained well three months after the onset of treatment |

| Sans et al., 199512 | 40, M | 30 | Shivering and myalgia | USG, CT, NMR and laparoscopic biopsy | Not available | Intermittent episodes of fever and muscle pain 2 years and 5 months after prednisone and azathioprine therapy |

| Hemaidan et al., 199913 | 61, M | 60 | Headache, myalgia, mental status changes, Sjögreńs syndrome | CT, autopsy | Not available | Symptoms maintained until death by sudden cardiac arrest |

| Papadaki et al., 200014 | 66, M | 90 | Anorexia, weight loss, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, chylous ascites | CT and laparotomy biopsy | Not available | Improvement in anemia and fever relief following prednisone and azathioprine with no change in the mesenteric lesions |

| Martínez Odriozola et al., 200315 | 59, F | 21 | None | CT and laparoscopic biopsy | Not available | Symptoms resolved after treatment with prednisone 1 mg/kg/d for 6 months |

| Ruiz García et al., 200716 | 55, M | >15 | Malaise and sweating | CT and open-surgery biopsy | Not available | Symptoms resolved after treatment with oral corticosteroids for 2 years |

| Ferrari et al, 200817 | 36, M | 42 | Chills, weight loss | Open-surgery biopsy | Not available | Symptoms resolved after treatment with oral corticosteroids for 5 months |

| Avelino-Silva et al., 2011 | 44, M | 10 | Fatigue and worsened constipation | CT and laparoscopic resection | Normal | Symptoms resolved after surgical treatment |

M = male; F = female; CT = computed tomography; USG = ultrasonography; NMR = nuclear magnetic resonance.

The best treatment for sclerosing mesenteritis remains unclear. Asymptomatic or mild clinical forms may sometimes be left untreated with spontaneous recovery (8). Surgical resection is required for patients with intestinal obstruction and perforation, and immunosuppressive therapy with corticosteroids, thalidomide, and other drugs has been recommended by some authors (7,8). In the present case, surgical removal was able to limit the process. The prognosis is mainly dependent on a correct diagnosis and on the extension of the fibrotic process (9).

Fever has not often been described as a symptom of sclerosing mesenteritis. In this case report, a long-lasting fever was the clinical hallmark of FUO. Although rare, physicians should be aware of this possibility.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONSAvelino-Silva VI conceived and coordinated the study and participated in the acquisition of data and manuscript writing. Leal FE participated in the design of the study, data acquisition and manuscript writing. Coelho-Netto C, Cotti GC, Souza RA, Azambuja RL, and Rocha MS participated in the acquisition of data and in manuscript writing. Kallas EG coordinated the study and participated in the acquisition of data and in manuscript writing.

This report is not a result of a specific funded grant. We acknowledge Professor Christopher D.M. Fletcher for his contribution to the histopathologic diagnosis.

No potential conflict of interest was reported.