To determine the frequency of the immunohistochemical profiles of a series of high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast.

METHODSOne hundred and twenty-one cases of high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ, pure or associated with invasive mammary carcinoma, were identified from 2003 to 2008 and examined with immunohistochemistry for estrogen receptor, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, cytokeratin 5, and epidermal growth factor receptor. The tumors were placed into five subgroups: luminal A, luminal B, HER2, basal-like, and “not classified”.

RESULTSThe frequencies of the immunophenotypes of pure ductal carcinoma in situ were the following: luminal A (24/42 cases; 57.1%), luminal B (05/42 cases; 11.9%), HER2 (07/42 cases; 16.7%), basal-like phenotype (00/42 cases; 0%), and “not classified” (06/42 cases; 14.3%). The immunophenotypes of ductal carcinoma in situ associated with invasive carcinoma were the following: luminal A (46/79 cases; 58.2%), luminal B (10/79 cases; 12.7%), HER2 (06/79 cases; 7.6%), basal-like (06/79 cases; 7.6%), and “not classified” (11/79 cases; 13.9%). There was no significant difference in the immunophenotype frequencies between pure ductal carcinoma in situ and ductal carcinoma in situ associated with invasive carcinoma (p>0.05). High agreement was observed in immunophenotypes between both components (kappa = 0.867).

CONCLUSIONThe most common immunophenotype of pure ductal carcinoma in situ was luminal A, followed by HER2. The basal-like phenotype was observed only in ductal carcinoma in situ associated with invasive carcinoma, which had a similar phenotype.

Breast cancer has a heterogeneous natural history and varying morphological and immunohistochemical profiles and prognoses. Until recently, the classification and therapeutic decisions regarding breast carcinoma were based on histological features and classical prognostic and predictive factors.

Recent cDNA microarray studies have identified distinct groups of tumors with disparate prognoses, resulting in a new classification of invasive breast carcinomas. Breast tumors are categorized into five subgroups based on their molecular profile: luminal A, luminal B, HER2, basal-like, and normal breast-like (1–3). Gene expression signatures and protein expression profiles through immunohistochemistry correlate well in invasive breast cancers (4–8).

The basal-like subtype has attracted the attention of researchers and physicians because it has been associated with poor clinical outcomes. These outcomes likely reflect this subtype's high proliferative capacity and the lack of directed therapies, as basal-like tumors do not typically express estrogen receptor or overexpress HER2 (2–3). The basal-like phenotype is more frequent among invasive tumors that have a high histological grade (9–11).

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) represents a precursor lesion to invasive breast cancer, in which most molecular alterations are already present (12). Based on this model, basal-like invasive ductal carcinomas, which are primarily high grade, arise from high-grade DCIS.

Many studies have evaluated invasive mammary carcinomas (IMCs), but few studies have examined the molecular profile of DCIS of the breast through immunohistochemistry. Assuming that DCIS is a precursor of invasive carcinoma, we expect that the molecular phenotypes previously described for IMC will also be identified among cases of DCIS.

The purpose of this study was to determine the frequency of the basal-like phenotype and other immunophenotypes in a series of cases of high-grade DCIS of the breast, either pure or associated with invasive carcinoma, to compare the frequency of immunohistochemical profiles in pure or IMC-associated DCIS cases and to assess the agreement of immunophenotypes between in situ and invasive components in DCIS cases that are associated with invasive components. We chose a specific subset of high-grade DCIS because the basal-like phenotype is more frequent among invasive tumors that have a high histological grade (9–11). By identifying basal-like DCIS, these tumors can be treated more aggressively than other DCIS subtypes to improve the prognosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODSSpecimen selectionIn total, 202 cases of high-grade DCIS, pure or associated with invasive carcinoma, were consecutively identified from the histopathology files of the Breast Pathology Laboratory, School of Medicine, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil, from 2003 to 2008. Seventy-one cases (35%) were excluded: 14 cases showed autolysis (7%), 32 cases received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (16%), 11 cases were a local recurrence following breast-conserving surgery (5%), and 14 cases had insufficient tumor tissue for sectioning (7%). The original hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections from 131 cases were reviewed to confirm the diagnosis of high-grade DCIS and select a representative block for immunostaining. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded blocks were not found in 10 cases (5% of the total). Thus, immunohistochemistry was performed in 121 high-grade DCIS cases (60% of the total).

The criteria defined by the World Health Organization (2012) were used for the histopathological diagnosis of DCIS (13). The DCIS histological grade was determined using the criteria of Scott et al., 1997 (14).

Clinical, tumor, and treatment featuresThe age at diagnosis, menopausal status, tumor size, primary surgical treatment, and adjuvant therapy were retrospectively evaluated.

Menopausal status was defined based upon in-person interview data.

ImmunohistochemistryEstrogen receptor (ER), HER2 overexpression, cytokeratin 5 (CK5), and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) were assessed. The reactions were performed with automated equipment (BenchMark XT/LT™ – Ventana, USA) using the UltraView Universal REF 760–500 DAB kit (Ventana, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The sources and dilutions of the primary antibodies are listed in Table 1.

Allred's scoring system was used to evaluate estrogen receptor status; cases were considered positive when at least 1% of neoplastic cells showed moderate or strong nuclear staining (15). HER2 overexpression was analyzed according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology and College of American Pathologists (16). Any degree of cytoplasmic staining for CK5 and any degree of distinct membranous staining for EGFR were considered positive expression (17).

Immunohistochemical profileThe tumors were divided into five subgroups according to their immunohistochemical profile: luminal A (ER+/HER2-), luminal B (ER+/HER2+), HER2 (ER-/HER2+), basal-like (ER-/HER2-/EGFR+ and/or CK5+), and “not classified” (all markers negative) (17,18). The basal-like phenotype was defined according to Nielsen's criteria (6).

Statistical analysisPearson's asymptotic and exact chi-square tests were used to compare proportions. The Mann-Whitney test was used to compare medians. A p-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The kappa test was used to assess the concordance between phenotypes. Kappa values greater than 0.80 demonstrated excellent agreement (19). This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (protocol 655/08).

RESULTSPure DCIS was detected in 46/131 cases (35% of the total), and 85/131 cases (65% of the total) were DCIS associated with invasive carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry was performed for 121 cases, including 42 cases of pure DCIS (35% of the total) and 79 cases of DCIS associated with invasive carcinoma (65% of the total).

The median age at diagnosis was 51 years (standard deviation ±14 years) among cases of pure DCIS and 53 years (standard deviation ±19 years) among cases of IMC-associated DCIS (p = 0.913). The median DCIS size was 13 mm. There was no significant difference in menopausal status (p = 0.779) or median tumor size (p = 0.836) between pure and IMC-associated DCIS cases. There was a significant difference in primary surgical treatment and adjuvant therapy between pure and IMC-associated DCIS cases (p<0.05). Cases with DCIS associated with IMC were treated with more extensive surgery and more often received adjuvant therapy.

The frequencies of the molecular immunophenotypes of DCIS are shown in Table 2 and Figure 1. Among samples of pure DCIS, the luminal A phenotype was the most common (24/42 cases; 57.1%), followed by the HER2 phenotype (07/42 cases; 16.7%), the “not classified” phenotype (06/42 cases; 14.3%), and the luminal B phenotype (5/42 cases; 11.9%). The basal-like phenotype was not identified among the pure DCIS cases. The immunophenotypes of DCIS associated with invasive carcinoma were the following: luminal A (46/79 cases; 58.2%), luminal B (10/79 cases; 12.7%), HER2 (06/79 cases; 7.6%), basal-like (06/79 cases; 7.6%), and “not classified” (11/79 cases; 13.9%).

Immunohistochemical profile of high-grade DCIS (pure or associated with invasive mammary carcinoma).

| Pure DCIS | DCIS + IMC | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotype | N (%) | N (%) | p-value∗) |

| Luminal A | 24 (57.1%) | 46 (58.2%) | 0.264 |

| Luminal B | 05 (11.9%) | 10 (12.7%) | |

| HER2 | 07 (16.7%) | 06 (7.6%) | |

| Basal-like | 00 (0%) | 06 (7.6%) | |

| “Not classified” | 06 (14.3%) | 11 (13.9%) | |

| TOTAL | 42 (100%) | 79 (100%) |

DCIS = ductal carcinoma in situ; IMC = invasive mammary carcinoma

Luminal A: ER+/HER2-; Luminal B: ER+/HER2+; HER2: ER-/HER2+; Basal: ER-/HER2-/EGFR+ and/or CK5+; “Not classified”: ER-/HER2-/EGFR-/CK5-.

p = significance level.

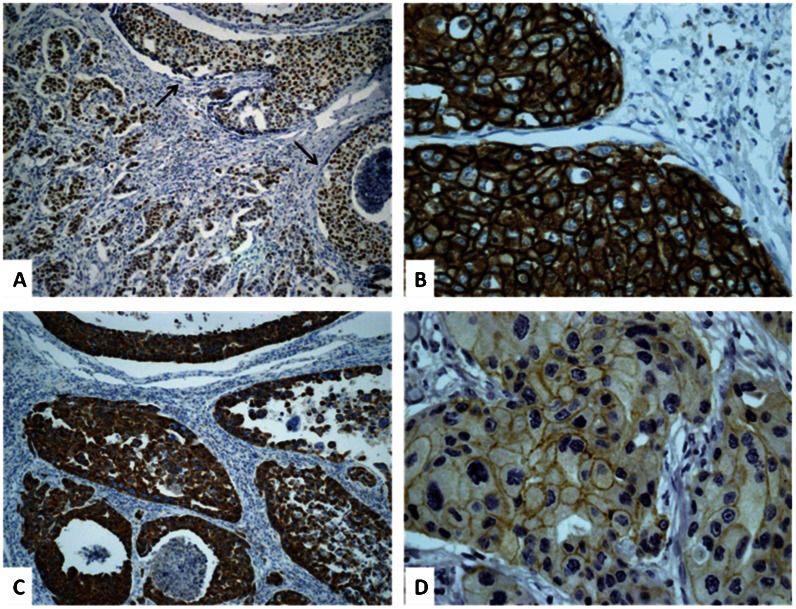

A) High-grade ductal carcinoma in situ associated with invasive mammary carcinoma positive for estrogen receptor (100x). Arrows indicate the in situ component. B) High-grade ductal carcinoma in situ positive for HER2 (400x). C) High-grade ductal carcinoma in situ positive for cytokeratin 5 (100x). D) High-grade ductal carcinoma in situ positive for epidermal growth factor receptor (400x).

There was no significant difference in frequency between immunophenotypes in pure and IMC-associated DCIS samples (p>0.05). Excellent agreement was observed between in situ and invasive components with regard to immunophenotypes (kappa = 0.867).

DISCUSSIONBreast cancer comprises a heterogeneous group of diseases with regard to presentation, morphology, biological characteristics, clinical behavior, and response to therapy (6,9,20). In the past 20 years, concomitant with the wide use of screening mammography, the DCIS incidence has risen dramatically (21–22). The understanding of the biology and clinical behavior of DCIS is currently limited. Molecular profiling through gene array studies is likely to have a major impact on breast cancer classification and management, and it is important that similar approaches are taken to advance the understanding of DCIS.

The immunohistochemical staining of paraffin sections using antibody panels has been shown to be a reliable surrogate for the molecular classification of invasive breast cancers through gene expression profiling studies. Antibodies against estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, HER2, cytokeratin 5/6, and EGFR have been particularly useful for this purpose (4–8). In fact, this approach to molecular classification (that is, using immunostaining as a surrogate for expression profiling) is arguably the most practical approach to phenotyping a large number of archived specimens for which fresh tissue is not available for expression array analysis.

Recent advances have led to an emerging molecular classification for invasive breast cancer based on the biological characteristics of the tumor rather than being limited to morphological analysis. Much less attention has been focused on dissecting the biological subtypes of DCIS, the immediate precursor to invasive breast cancer. There have been discrepancies in the results of those studies. There have also been discrepancies in the relative frequency of subtypes between in situ and invasive disease (17,20,23–26).

In our series, we showed that DCIS can be classified into the five immunophenotypes that have been described for invasive breast carcinomas using a panel of four markers. Molecular classification improves the current morphological classification and provides insight into the biology underlying DCIS heterogeneity.

Previous studies have evaluated the immunoprofiles of DCIS independently of histological grade (17,20,23). Bryan et al. restricted their study to high-nuclear-grade DCIS lesions because basal-like invasive carcinomas are poorly differentiated tumors in histopathological studies (24). In our study, we chose a specific subset of high-grade DCIS of the breast to determine the frequency of the basal-like phenotype because this subtype is more frequent among invasive tumors that have a high histological grade (9–11,24).

Basal-like tumors have attracted the attention of pathologists, surgeons, and oncologists and constitute a prognostic group of breast cancers with aggressive behavior. These tumors affect younger patients, are more prevalent in African-American women, and exist more often as interval cancers (18). Basal-like tumors are candidates for specific targeted therapy. By identifying basal-like DCIS, surgeons and oncologists can likely treat these tumors more aggressively to improve the prognosis.

There is no consensus regarding markers that define basal-like tumors by immunohistochemistry (11). Some groups have suggested that basal-like tumors are triple negative, i.e., negative for estrogen and progesterone receptors and HER2. However, the triple-negative phenotype is not synonymous with the basal-like phenotype (9,27). Other authors consider the basal-like phenotype as showing positivity for basal cytokeratins, regardless of the expression of other markers (5). EGFR positivity, which is associated with positivity for basal cytokeratins and negativity for estrogen receptor and HER2, defines basal-like breast cancers for other authors (6,17–18). EGFR gene amplification and/or high EGFR expression are biological predictors of poor prognosis in breast carcinomas. EGFR has also been used as a marker of the basal phenotype and has been investigated as a potential target therapy for human breast cancer (17–18). In our study, we classified the basal-like phenotype according to Nielsen's criteria (6), which includes EGFR evaluation.

Our data demonstrated good agreement between the molecular profile of DCIS and synchronous IMC with regard to immunohistochemical phenotypes. Contemporary models suggest that high- and low-grade invasive ductal cancers arise through disparate pathways: high-grade IMC develops directly from poorly differentiated DCIS rather than low-grade IMC or low-grade DCIS. DCIS represents a stage in the development of breast cancer in which most molecular alterations are already present [12,28). Based on this model, basal-like invasive ductal carcinomas, which are primarily high grade, arise from high-grade DCIS. Until recently, however, a basal-like in situ component was not known to exist.

Livasy et al., Paredes et al., Bryan et al., and Clark et al. observed the following frequencies of the basal phenotype in pure DCIS: 8%, 10.1%, 6%, and 4.2%, respectively (17,23–24,26). In our study, the basal-like phenotype was not identified among pure DCIS. We identified the basal phenotype in 7.6% of IMC-associated DCIS cases. Tamimi et al. observed a similar frequency (7.7%) of the basal phenotype for the in situ component (20). This difference in frequencies might be related to the criteria used to classify tumors as well as variables from the preanalytical and analytical phases of immunohistochemical reactions, such as the choice of primary antibodies. According to the tumor type-specific evolution from DCIS to invasive carcinoma (28), another possible interpretation of these differences in frequencies is that the DCIS lesions in the cited papers were diagnosed at different stages of progression.

Our data showed an increased frequency of the HER2 phenotype in pure high-grade DCIS, which is consistent with previous studies demonstrating a higher prevalence of HER2 protein overexpression and gene amplification among DCIS in comparison to invasive breast cancers and suggesting that HER2/neu gene amplification is inversely related to invasive progression in DCIS patients (28–29).

We did not observe a significant difference in the frequencies of molecular phenotypes in pure or IMC-associated DCIS. Tamimi et al. showed differences in the frequencies of luminal A, luminal B, and HER2 phenotypes in pure DCIS versus invasive breast cancers, but there was no difference in the basal-like phenotype and “not classified” cases (20).

We did not observe the basal-like phenotype in pure DCIS, despite the presence of this profile in IMC-associated DCIS cases. Based on the tumor type-dependent model of breast cancer progression from DCIS to invasive cancer, triple-negative cancers may progress much faster than the other three tumor types, suggesting that some unrecognized mechanisms or features might help these tumors progress. At the time of breast tumor diagnosis, more aggressive types will have fewer DCIS lesions in comparison to the less aggressive types, with more tumors still in the DCIS phase. With regard to the speed of becoming invasive breast cancers, the fastest are the triple-negative lesions, while pure HER2-positive tumors are almost three times slower. Luminal A and luminal B DCIS are two tumor types that show intermediate probabilities of progression to invasive carcinoma (28). Therefore, our results are in agreement with the tumor type-dependent model of breast cancer progression from DCIS to invasive cancer.

In conclusion, immunophenotypes that were previously identified among invasive mammary carcinomas were also observed among cases of DCIS. The most common immunophenotype of pure DCIS was luminal A, followed by the HER2 phenotype. The basal-like phenotype was observed only in DCIS associated with invasive carcinoma, which had a similar phenotype. No significant difference was identified between pure DCIS and IMC-associated DCIS phenotypes. There is a critical need for prospective analyses of new and known breast cancer molecular markers in large cohorts of patients with DCIS to differentiate indolent from aggressive DCIS and better tailor the need and extent of current therapies.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONSPerez AA conceived the study, participated in the review of the original slides and analysis of the immunohistochemical reactions, and drafted the manuscript. Rocha RM performed the immunohistochemical reactions. Balabram D performed the statistical analysis. Souza AS separated the original slides and blocks for immunohistochemistry. Gobbi H participated in the design and coordination of the study, review of original slides, and analysis of the immunohistochemical reactions and helped drafting the manuscript. All of the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

We are grateful to Sandra J. Olson, MBs, for editing the manuscript for language. This work was supported in part by grants from Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa de São Paulo (FAPESP), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES).

No potential conflict of interest was reported.