Osteomalacia is one of the most common osteometabolic diseases among the elderly and may be associated with osteoporosis.1 It is typically caused by lack of vitamin D and is characterized by mineralization deficiency of the osteoid matrix in the cortical and trabecular bone, resulting in accumulation of osteoid tissue.2 Vitamin D deficiency is a pathogenic factor of osteoporosis that can be modified.5, 9 The elderly are at particularly high risk for developing osteomalacia, which is frequently misdiagnosed.1, 3

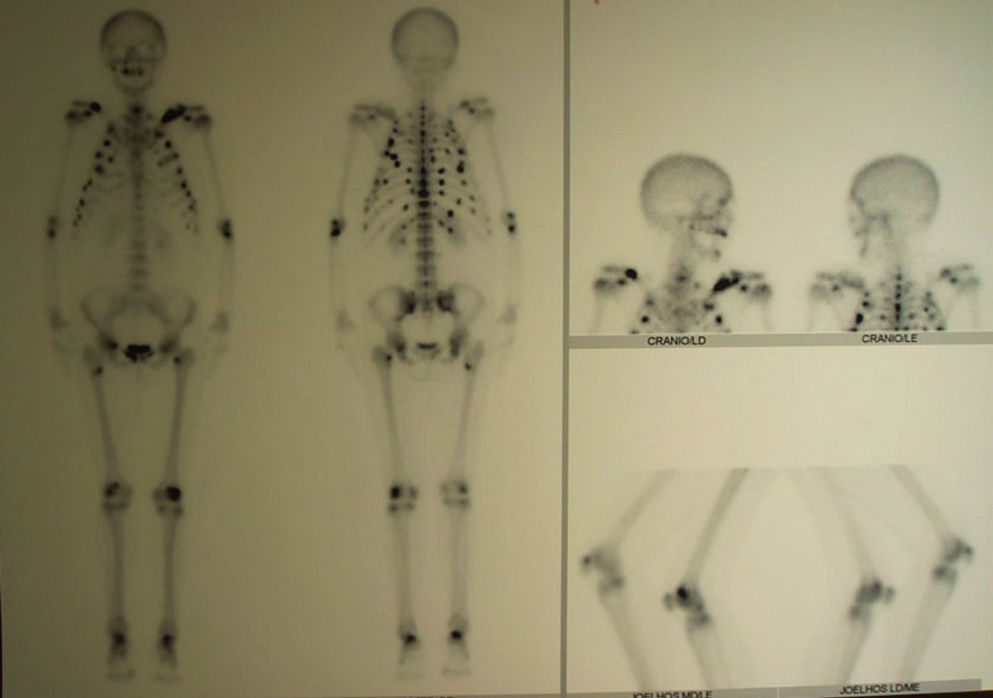

SAMPLE AND METHODSWe report the case of a 62-year-old woman who had experienced body pains and weakness for two years. She had suffered from multiple fractures of the ribs and the left clavicle without trauma for two months before she was admitted to the hospital. Comorbidities included hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, depression and neurological sequelae with left hemiparesis. The patient was using levothyroxine, omeprazole, metformin, glymepiride, milnacipran, mirtazapine and atenolol. Radiography showed fractures of nine costal arches and of the left clavicle. Bone scintigraphy revealed multiple osteogenic reaction areas, with predominance in the axial skeleton (Figure 1). Bone densitometry showed osteoporosis with a lumbar spine (L1–L4) T score of −3.1 and a femur (neck) T score of −2.8. The laboratory test results showed alkaline phosphatase (AP) 491 U/L (RR-ref range < 104 U/L); parathyroid hormone (PTH) 146 pg/ml (RR 7–62 pg/ml); total serum calcium 8.5 mg/dl (RR 8.6–10.2 mg/dl); ionized calcium 4.7 mg/dl (RR 4.6–5.3 mg/dl); serum phosphorus 3.6 mg/dl (RR 2.7–4.5 mg/dl); urinary calcium 42.3 mg/24h (RR 100–320 mg/24h); and urinary phosphate 397.4 mg/24 h (RR 400–1300 mg/24h).

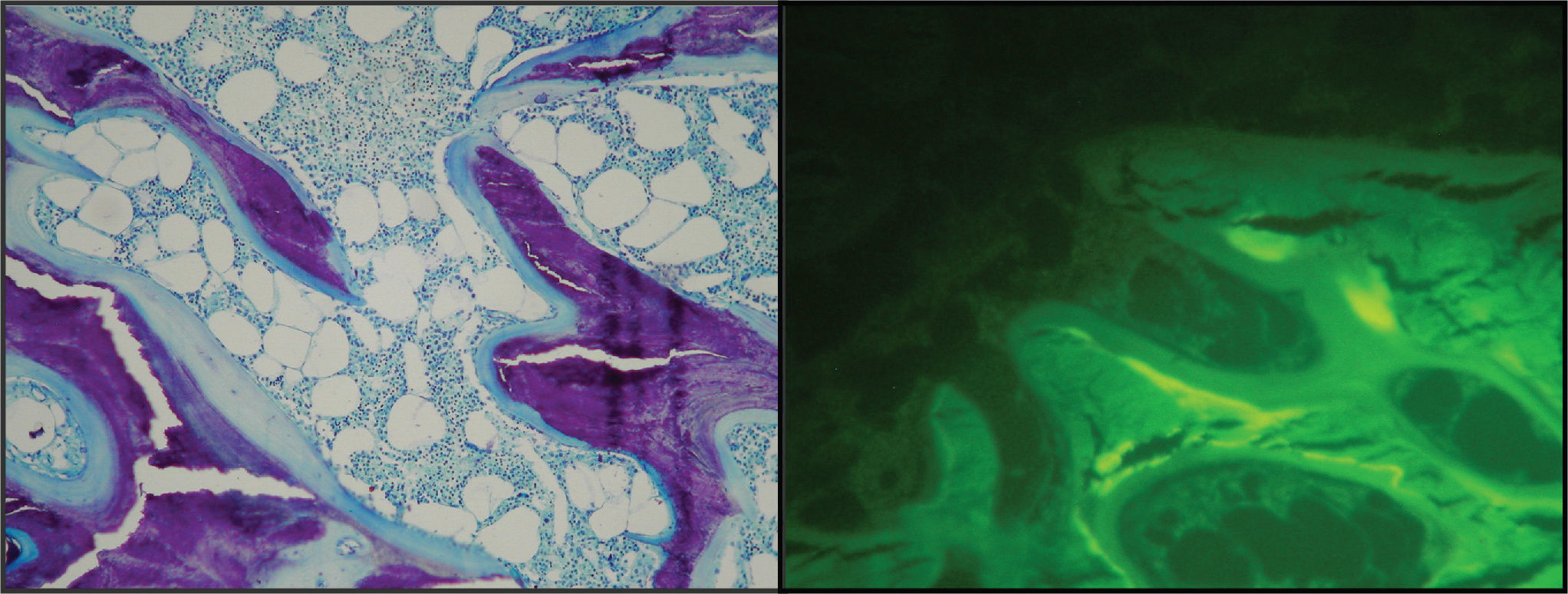

These findings led us to hypothesize that the patient had osteomalacia. It was decided to perform a trans-iliac bone biopsy. The patient was pre-labeled with oral tetracycline (20 mg/kg/day for 3 days) administered over two separate intervals 10 days apart.

The biopsy revealed diminished trabecular volume (13.3%), increased osteoid surface (82%) and volume (43%), and confluent tetracycline labeling (Figure 2); thus, the hypothesis was confirmed. Serum 25-OH-vitamin D levels were determined to be 11 ng/ml (RR > 40 ng/ml). The patient was prescribed calcitriol at 0.75 mg/day and 2 g of calcium carbonate to normalize PTH and alkaline phosphatase (AP) levels. Body pains and weakness were eventually reduced. Over a follow-up period of three years, the patient did not have any new fractures. Her bone mineral density improved by 38% in the lumbar spine (L1-L4 T-score −0.56) and 67.3% in the femur (neck T-score −1.21). Laboratory test levels had normalized to alkaline phosphatase (AP) 81 U/L (RR-ref range < 104 U/L); parathormone (PTH) 53 pg/ml (RR 7–62 pg/ml); total serum calcium 9.4 mg/dl (RR 8.6–10.2 mg/dl); ionized calcium 4.9 mg/dl (RR 4.6–5.3 mg/dl); serum phosphorus 4.4 mg/dl (RR 2.7–4.5 mg/dl); urinary calcium 151 mg/24 h (RR 100–320 mg/24 h) and serum 25-OH-vitamin D 42 ng/ml (RR > 40 ng/ml). At present, the patient is using colecalciferol at 1000UI a day with good results.

DISCUSSIONVitamin D plays a role in bone mineralization and in the regulation of circulating calcium. Deficiency of this vitamin results in increased parathyroid hormone (PTH) synthesis and secretion.5 This secondary hyperparathyroidism increases bone turnover, resulting in increased risk of fracture.1 Osteomalacia develops when this process is intense and chronic and was histologically apparent in 13 to 33% of patients with osteoporotic femoral neck fractures.1, 5

Vitamin D deficiency has been implicated in osteoporotic pathophysiology of the elderly and can cause muscle weakness as well as predisposition to falls and fractures. Osteomalacia may be associated with fractures due to minimal stress trauma and should be suspected when laboratory exams show increased levels of alkaline phosphatase (AP) with normal or decreased serum calcium and phosphorus, increased PTH (secondary hyperparathyroidism), and absence of lithic lesions and neoplasic bone disease. In most cases, osteomalacia can be diagnosed by assaying for 25-OH-vitamin D,8 which can be useful for early detection of the deficiency. Vitamin D3, or cholecalciferol, is synthesized in the skin by ultraviolet radiation from the sun. In order to become active, it must furthermore undergo two hydroxylations in the liver and kidneys.5 Low intake, poor absorption, and insufficient exposure to the sun can all result in Vitamin D deficiency. In some cases, the defect occurs in the receptor, and the diagnosis can only be confirmed through bone biopsy, which also allows for differentiation between osteomalacia and osteoporosis.2

Cancer and prolonged use of anticonvulsants such phenytoin can also cause osteomalacia. The main differential diagnosis is osteoporosis, which shows normal results on biochemical tests for calcium, phosphorus, AP and PTH. Vitamin D deficits among the elderly have been reported in several countries,1,3,4,8 even in Brazil, despite its tropical location.5 Vitamin D deficiency has been implicated in various pathological conditions including osteoporosis, muscle weakness and predisposition to falls and fractures.4,7,10,11 Epidemiological studies suggest that adequate serum concentrations of Vitamin D are related to reduced risk of autoimmune diseases, falls,9 and prostate, colon, breast and ovarian cancer.6,9

CONCLUSIONVitamin D deficit may cause osteomalacia, which should be included in the differential diagnosis for fractures caused by minimal trauma. It is suggested that Vitamin D assays should be included in routine assessments of the elderly and that Vitamin D supplementation should be considered even in tropical countries.