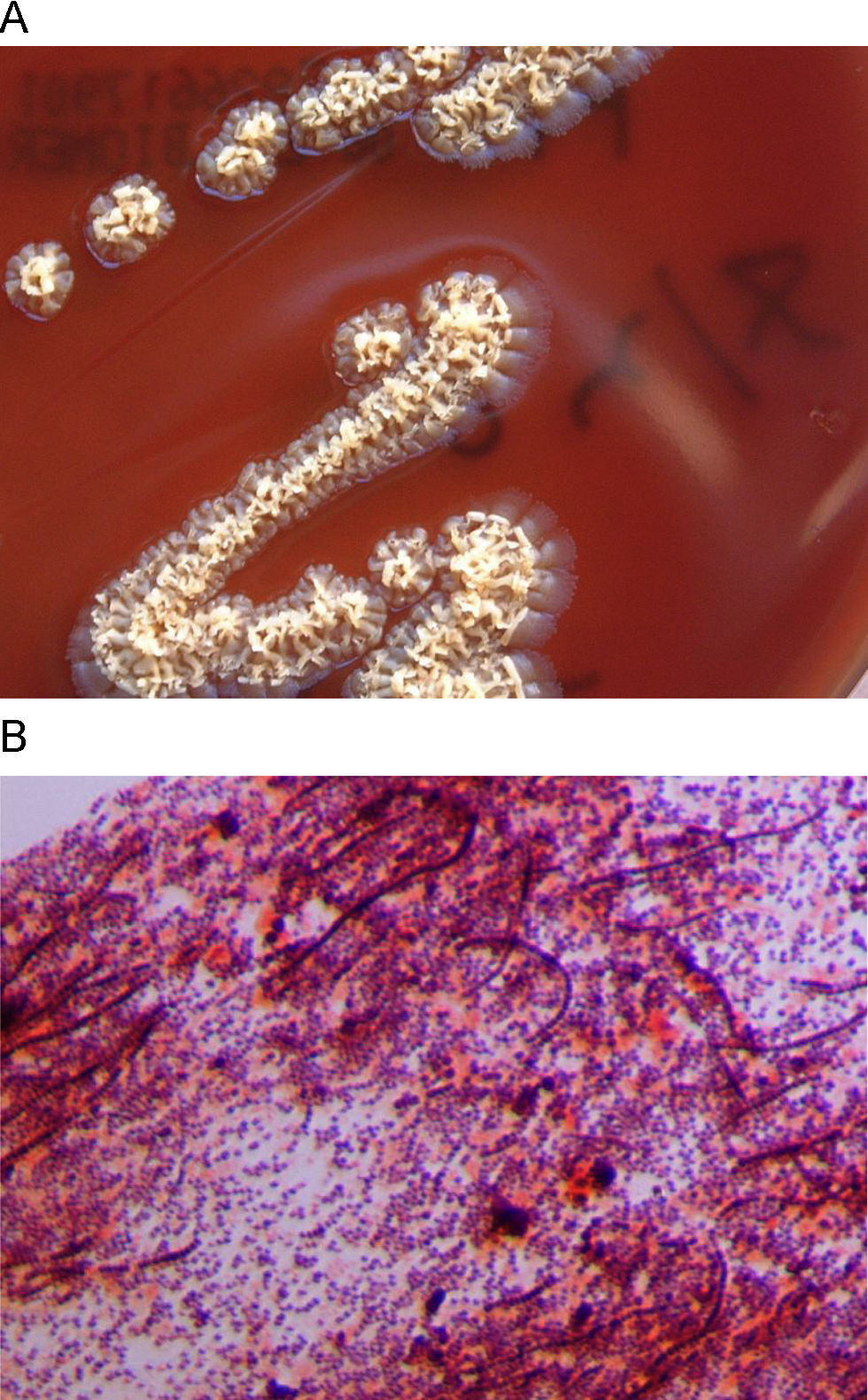

A 25 year-old woman with no notable history presented with a rash that appeared two weeks before, during a journey to Thailand. She noticed the lesions after bathing in a lake in which there were elephants and other exotic animals. The rash began as little reddish spots on both legs, which turned into papules and in some cases into pustules. Skin examination revealed multiple papules or little round reddish plaques with well defined borders on both legs. The rash was not painful but was mildly pruritic. The patient did not refer to any other symptoms. There was no fever, and routine laboratory analyses were within normal ranges. A skin biopsy was taken for histopathological and microbiological studies. After 4 days, an organism grew in a normal blood culture and on chocolate and Brucella agar plates. Colonies were yellowish, slightly beta-haemolytic, irregular, rough, and produced pits in the agar medium (Fig. 1A). Biochemical tests were positive for β -haemolysis, catalase, urease, gelatin hydrolysis, and growth at 35°C, acid from glucose and fructose, arginine dihydrolase, pyrrolidonyl arylamidase. Gram staining showed gram-positive coccoid forms, some of them associated in parallel rows of chains, and long, irregular filaments, sometimes with transverse septa (Fig. 1B). Primers based on the agac gene, coding for an alkaline ceramidase specific for D. congolensis (GenBank accession number AJ496026),1 were designed. PCR/sequencing led to a 2090 bp fragment which was identified as belonging to the alkaline ceramidase specific for D. congolensis. The microorganism was also identified by mass spectrometry, using a MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry device and the MALDI BioTyper software (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Leipzig, Germany).2 MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry also identified the microorganism as D. congolensis with a score of 1.96 (identification reliable at the genus level according usual MALDI-TOF recommendations). The histopathological study showed an epidermis with variable thickness and irregular psoriasiform pattern, with spongiosis, neutrophils, local hyperkeratosis and, occasionally, intracorneal pustules. Dermatophilosis is a cutaneous infection caused by Dermatophilus congolensis, a facultative anaerobe, actinomycetal gram-positive microorganism primarily known as an animal pathogen, associated to acute and chronic dermatitis. Though animal dermatophilosis has been reported in several countries in Europe,3 no human dermatophilosis (HD) cases have been previously reported in Europe, and a small number of HD have been described worldwide, mainly in the United States, Australia and Africa. Most cases are skin infections associated to contact with animals, and the clinical presentation can be very heterogeneous.3–8 In clinical samples, Dermatophilus appears as branching microorganisms which develop both transverse and longitudinal septa. Septation results in the formation of chains of coccoid cells in up to eight parallel rows.3,5 These coccoid cells, under favourable conditions (mainly humid environments) can be released and lead to flagellated, motile zoospores, which are the infective form. The zoospores then lead to germ tubes that develop into branching filaments, the invasive form of the organism.7 After 24h of incubation, colonies appear beta-hemolytic, small, irregular, heaped, rough, yellowish (grey or orange colonies may appear sometimes) and produce pits in the agar medium.4,7 The organism does not grow on MacConkey, Sabouraud and Lowenstein-Jensen agar.7

Infection leads to the formation of scabs harbouring D. congolensis, which can be a source for transmission. In a dry environment, the zoospores can remain inactive in the scab for months. When there is sufficient humidity, the zoospores reactivate and become invasive. This high humidity level seems to be decisive for infectivity.3,5

Authors gratefully acknowledge Prof. Juan Luis Muñoz Bellido (Departamento de Microbiología, Hospital Universitario de Salamanca) for his help in the conventional and molecular identification of the microorganism and the preparation of the manuscript, and to Prof. Jose Manuel González-Buitrago Arriero (Unidad de Investigación, Hospital Universitario de Salamanca) for his help in MALDI-TOFF identification.