Osteoarticular infection frequently remains microbiologically unconfirmed in the pediatric age.1 Since the early 1990s Kingella kingae has emerged as a major etiological agent of osteomyelitis and septic arthritis in children aged less than 4 years.2 Recently, the implementation of molecular detection assays (MDA) has established the real role of this microorganism in osteoarticular infections.2–5

We conducted a retrospective study in a cohort of pediatric patients (<18 years at inclusion) diagnosed with septic arthritis and osteomyelitis between January 2012 and May 2016 at Hospital Sant Joan de Déu (Barcelona). Samples were obtained through arthrocentesis or arthrotomy in arthritis and bone debridement in osteomielitis. Depending on the volume of the drained material, samples were partly inoculated in situ in aerobic blood culture bottles (SBCB) (BacT/ALERT, BioMérieux; USA) by the orthopedic surgeon. In febrile patients, blood cultures (BC) from peripheral veins were also obtained. Samples were processed by means of routine microbiological procedures (gram staining; blood agar, blood anaerobic agar, chocolate agar and tioglicolate medium cultures), inoculated in BCB, when it was not previously done, and to be tested by specific real-time PCR.

PCR targeting the rtxA toxin gene of K. kingae (accession number EF067866) slighted adapted from a previously PCR design.5 The primers and probe used in our site were KK-forward (5′-GCGCACAAGCAGGTGTACAA-3′), KK-reverse (5′-ACCTGCTGCTACTGTACCTGTTTTAG-3′) and the TaqMan probe (6FAM-5′-CTTTGAACAAAGCTGGACACGCAGC-3′-BBQ). Real-time for LytA gene of Streptococcus pneumoniae and CtxrA gene for Neisseria meningitidis were also performed.6,7

During the study period, samples from 88 patients (42.0% females, median [IQR] age: 2.1 [1.2–6.8] years) were processed. In 51 (58.0%) patients, blood cultures were also performed. Diagnosis included 67 septic arthritis and 21 osteomyelitis.

Overall, 49 cases (55.7%) were microbiologically confirmed, including 38 (56.7%) cases of septic arthritis and 11 (52.4%) cases of osteomyelitis. K. kingae (25 cases, 51%) and Staphylococcus aureus (18 cases, 36.7%) were the most frequent pathogens. Hip (13), knee (11), ankle (8), elbow (4), shoulder (2) tibia (5), femur (2) ulna (1), fibula (1), astragalus (1) and sternum (1) were the joins and bones affected.

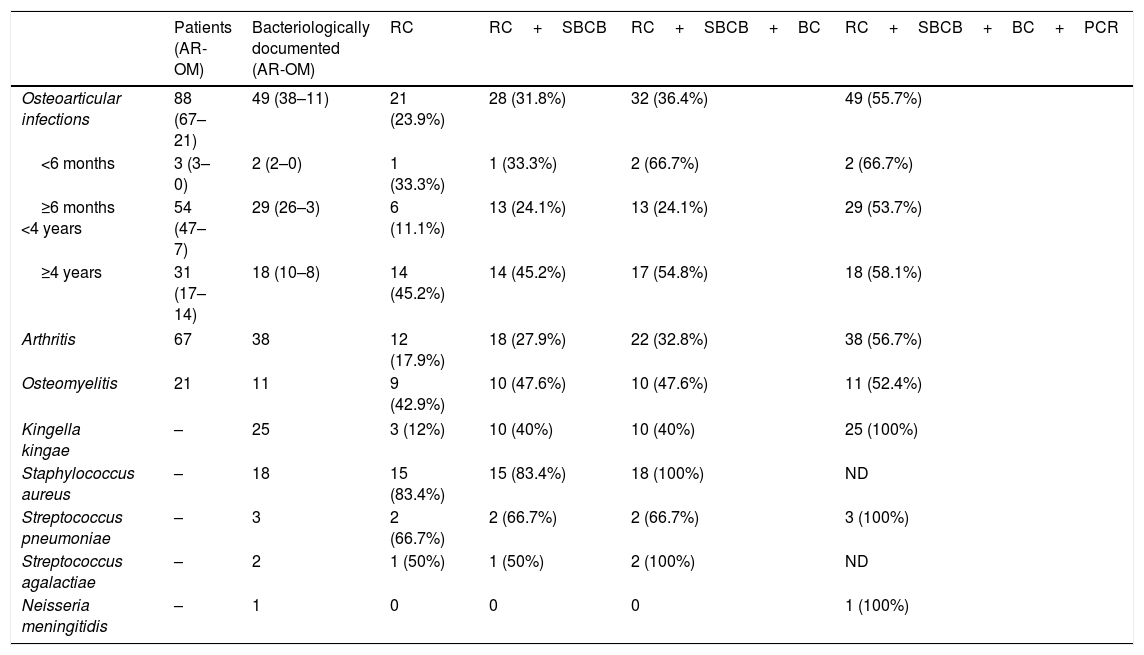

Table 1 shows the distribution of culture and real-time PCR results in patients with microbiologically confirmed osteoarticular infection according to the clinical diagnosis, the age and the species detected.

Distribution of culture and molecular methods results in patients with microbiologically osteoarticular infection according to disease type (septic arthritis or osteomyelitis), age and the species detected.

| Patients (AR-OM) | Bacteriologically documented (AR-OM) | RC | RC+SBCB | RC+SBCB+BC | RC+SBCB+BC+PCR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteoarticular infections | 88 (67–21) | 49 (38–11) | 21 (23.9%) | 28 (31.8%) | 32 (36.4%) | 49 (55.7%) |

| <6 months | 3 (3–0) | 2 (2–0) | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (66.7%) | 2 (66.7%) |

| ≥6 months <4 years | 54 (47–7) | 29 (26–3) | 6 (11.1%) | 13 (24.1%) | 13 (24.1%) | 29 (53.7%) |

| ≥4 years | 31 (17–14) | 18 (10–8) | 14 (45.2%) | 14 (45.2%) | 17 (54.8%) | 18 (58.1%) |

| Arthritis | 67 | 38 | 12 (17.9%) | 18 (27.9%) | 22 (32.8%) | 38 (56.7%) |

| Osteomyelitis | 21 | 11 | 9 (42.9%) | 10 (47.6%) | 10 (47.6%) | 11 (52.4%) |

| Kingella kingae | – | 25 | 3 (12%) | 10 (40%) | 10 (40%) | 25 (100%) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | – | 18 | 15 (83.4%) | 15 (83.4%) | 18 (100%) | ND |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | – | 3 | 2 (66.7%) | 2 (66.7%) | 2 (66.7%) | 3 (100%) |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | – | 2 | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) | 2 (100%) | ND |

| Neisseria meningitidis | – | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100%) |

RC: Routine culture.

SBCB: Osteoarticular sample in blood-culture bottle.

BC: Blood culture.

PCR: Molecular methods.

AR: Arthritis.

OM: Osteomyelitis.

Streptococcus agalactiae was isolated in 2 out of the 3 cases of septic arthritis diagnosed in patients younger than 6 months.

All 25 cases (92% with septic arthritis) of osteoarticular infections caused by K. Kingae were observed in patients aged between 6 months and 4 years. Only 10 (40%) strains of K. kingae were identified by one of the culture methods used (10 in SBCB and 3 also in routine cultures), but 100% of them tested positive by real-time PCR. In patients aged over 4 years (54.8% with septic arthritis) S. aureus was the most frequent pathogen and was found in 17 (54.8%) out of 31 cases. Most S. aureus isolates (15 out of 18) grew both in BCB and routine culture, while the other 3 were only isolated in BC.

Etiological diagnosis was exclusively attributable to real-time PCR in 17 out of 49 cases (34.7%).

Overall, patients with arthritis were younger (1.5 vs 6.5 years) and more often diagnosed with K. kingae infections (34.3% vs 9.5%) than those affected with osteomyelitis.

This study shows that the bacterial etiology of osteoarticular infections in children is closely related to the age of patient, and clearly outlines three different periods. During the first months of life osteoarticular infection is an infrequent event but usually caused by group B streptococci, as in late-onset neonatal sepsis.8K. kingae almost exclusively affects infants and toddlers, in fact, in 22 out of 25 (88%) K. kingae cases, patients were aged between six months and two years. Because K. kingae osteoarticular infections usually associate negative gram stain (100% in this study), mild clinical symptoms and mild alteration of plasmatic inflammation markers,2 differential diagnosis with non-infectious causes of arthritis (i.e. transient synovitis of the hip) is difficult.9 In these cases, culture in SBCB is important to isolate the microorganism,2 but MDA are critical for proper diagnosis and early treatment. That is why, specific K. kingae MDA should be available as a routine test in hospitals with pediatric patients. MDA also improve the detection of S. pneumoniae and N. meningitidis.

In patients aged >4 years, S. aureus remains the main cause of both arthritis and osteomyelitis,5 in our study 94.4% cases. Due to the efficiency of routine cultures for S. aureus, inoculation of samples in BCB does not improve the isolation rate. Moreover, previous studies have shown that S. aureus-specific PCR assays offer no advantages over classical cultures.3,10

FundingThis study has not received specific funding.