A 70-year-old man sought treatment for skin lesions on his left shoulder, trunk and thighs over the previous 7 days, as well as, since the previous day, a fever of 38.5 °C, polymyalgia, headache and general malaise. He reported no medical history of note and denied having recently used any medication or having received any insect bites. He worked at a hunting reserve in Zaragoza, in contact with dogs, rabbits, roe deer, wild boars and partridges.

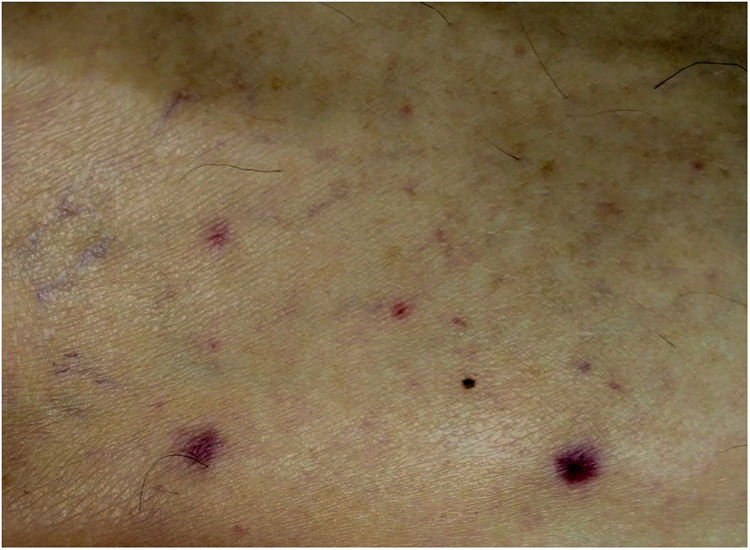

Examination revealed 2 indurated erythematous/oedematous plaques measuring around 3 cm on his left shoulder with central black spots (Fig. 1) and a faint rash consisting of small erythematous papules on his trunk and thighs (Fig. 2). He had no palpable lymphadenopathy. Blood tests showed elevated C-reactive protein, leukopenia, lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia.

As an infectious rash was suspected, serologies were ordered and a skin biopsy was performed, yielding a positive result for Rickettsia conorii IgM antibodies. Histology testing found a marked oedema on the superficial dermis, accompanied by chronic perivascular inflammatory infiltrate with a predominance of lymphocytes, plus endothelial cell swelling and haematic extravasation, all consistent with vasculitis.

Clinical courseThe patient was diagnosed with rickettsiosis and treatment was started with doxycycline 100 mg every 12 h, with complete resolution of the patient's signs and symptoms in 12 days. In addition, given the patient's atypical clinical signs, molecular testing was done by PCR using a fragment of the ompA and ompB genes as a target, and a sample was acquired by swabbing the spot; this confirmed rickettsiosis caused by Rickettsia sibirica mongolitimonae.

Closing remarksIn recent years, the development of new diagnostic techniques, particularly molecular methods, has enabled the characterisation of new species and subspecies of rickettsias that have proven to be pathogenic for human beings. Consequently, in Europe and Spain, when presented with signs and symptoms raising suspicion of Mediterranean spotted fever, clinicians cannot limit themselves to considering Rickettsia conorii as the sole pathogenic species.1,2

Emerging species include Rickettsia sibirica mongolitimonae, which was first isolated in Hyalomma asiaticum ticks in 1991 in Mongolia;3 the first case in humans was reported in 1996 in southern France.4 Since then, around 40 new cases of infection with this subspecies have been reported, the vast majority in Mediterranean countries and in a number of African countries.5,6 Other ticks, such as Rhipicephalus pusillus and Rhipicephalus bursa, have also been confirmed to act as vectors in Spain.5

Clinically, although a combination of multiple black spots, regional lymphadenopathy and lymphangitis was initially reported to be characteristic, so much so that the condition came to be called lymphangitis-associated rickettsiosis (LAR),2 more than half of cases have been seen to present signs and symptoms similar to Mediterranean spotted fever, with fever, myalgia, headache and one or more transmission spots, with no lymphadenopathy or lymphangitis.5,6 Furthermore, although it has not been associated with any deaths, complications such as retinal vasculitis, hyponatraemia, septic shock, myopericarditis, acute kidney failure and encephalitis have been reported.5–7

Regarding diagnosis, it should be borne in mind that, although serology is the most commonly used test, it not only carries a risk of false negatives in the initial stages of the disease, but it also often shows cross-positivity for different species of rickettsias. Therefore, in suspected cases, it is advisable to perform molecular testing by PCR and acquire the sample by means of a smear by swabbing of the spot.2,5–8

Thus, it is important to take into account that infections caused by different species of rickettsias may cause the same clinical manifestations; i.e. signs and symptoms typical of Mediterranean spotted fever often caused by these emerging species. It must also be remembered that rickettsias may also cause different clinical conditions, as in our case, owing to which it is important to maintain a high degree of suspicion and, if possible, attempt to characterise the rickettsia species by PCR testing.5,8

Please cite this article as: Sánchez Bernal J, Lorda-Espés M, Álvarez-Salafranca M, Ara-Martín M. Escaras necróticas y exantema cutáneo con fiebre en un trabajador en coto de caza. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2021;39:100–101.