Erythema nodosum (EN) is a well defined cutaneous syndrome that can be primary or secondary to systemic and autoimmune diseases, inflammatory bowel disease, pregnancy, neoplastic diseases, drugs or infections.1 Between infectious agents, Streptococci and Mycobacterium tuberculosis are the most common causes in developed and developing countries, respectively. Many other microorganisms have been involved in EN, but Rickettsia spp. have only been related in very few case reports.2,3

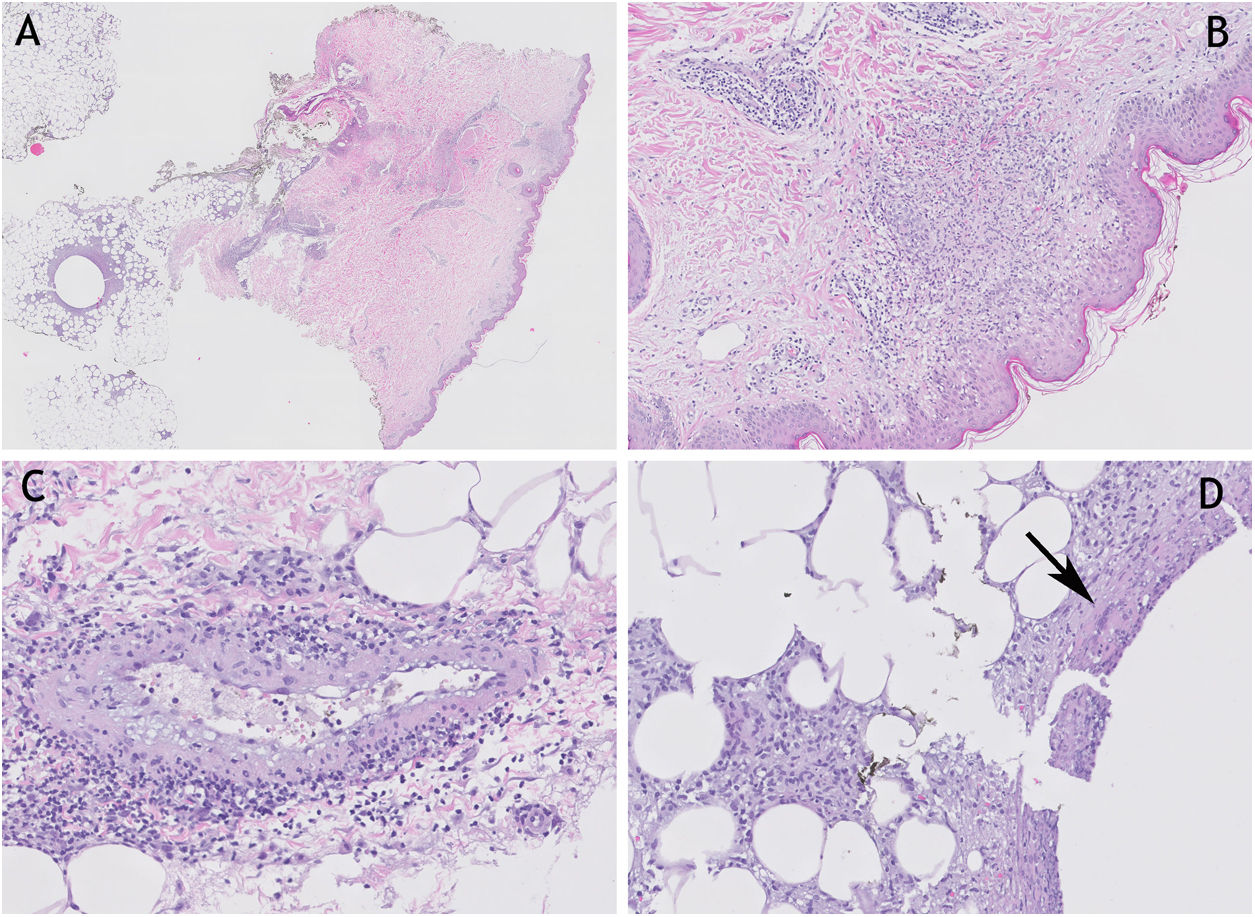

A 30-year-old woman without any previous diseases, had a property vaccinated dog and lived in a rural area. In mid-autumn she began suffering fevers of up to 38°C, headache, stiff neck and vomiting, so she went to the Emergency Department of our hospital. Upon arrival, blood pressure was 110/78mmHg, heart rate 124 beats per minute and oxygen saturation by pulse-oximetry was 100%. At physical exploration, neurological examination was normal; she had a black, scabby and painless skin lesion on her scalp, as well as multiple red, indurated and painful lesions on palpation in both lower limbs, suggestive of EN. A blood test was performed: CRP of 270mg/L, procalcitonin of 1.41ng/mL, neutrophilia of 8710/μL with lymphopenia of 770/μl and discrete prolongation of prothrombin time (15.5s). CSF analysis was normal, and CSF, blood and urine cultures were all negative. Chest x-rays and abdominal ultrasound were normal too. The patient was admitted to the Infectious Diseases Unit. A skin biopsy from one of the lesions in the lower limbs was taken (Fig. 1).

(A) (H&E 20×) cutaneous punch in which superficial, deep dermis and adipose panniculus are appreciated. (B) (H&E 200×) detail of lichenoid dermatitis with vacuolar degeneration of basal epidermal layer, and underlying granulomatous reaction. (C) (H&E 200×) medium-sized vessel with vacuoleated endothelium and enveloping lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate. (D) (H&E 400×) lobular and septal panniculitis with presence of giant multinucleated cell (arrow). H&E: hematoxylin and eosin.

On the day after admission, the patient referred blurred vision. An Ophthalmologist found mild vitritis, retinal vasculitis, patchy retinitis and severe papillitis in her right eye, as well as mild patchy vasculitis in the posterior pole of her left eye.

ANA, antiDNA and ENA antibodies were all negative. Serologies for Coxiella burnetii, HIV, VEB and CMV were negative but Rickettsia spp's serology was positive IgM and negative IgG (Chemiluminiscent immunoassay or CLIA; Rickettsia conorii Virclia, Vircell®: Moroccan strain ATCC VR-141). At that moment, doxycycline 100mg every 12h was initiated for 7 days, along with corticosteroids to treat the ocular disease. The patient became afebrile 36h after starting doxycycline. She improved quickly and could be discharged home. New serologies were made against Rickettsia spp in successive weeks: positive IgM and negative IgG persisted 2 weeks later; 3 months later, serology was still IgM positive by CLIA but undetermined IgM (1/40; Rickettsia conorii IFA IgM, Vircell®: Moroccan strain ATCC VR-141) and positive total antibodies by immunofluorescence assay (IFA).

The dermatological manifestations of rickettsiosis can be diverse. An eschar with epidermal necrosis at the site of inoculation is characteristic (tache noire). In addition, this infection can cause generalized vasculitis with involvement of the intima and media with vascular and perivascular infiltration of polymorphonuclear cells, lymphocytes and histiocytes. Other findings rarely seen are blood extravasation in petechial lesions, vacuolization of basal epidermal layers, and even intraepidermal vesicles with inflammatory infiltrate in the papillary dermis; EN is very uncommon. Cutaneous lesions in the form of a maculopapulopetechial rash with palmoplantar involvement are very characteristic of Rickettsia conorii, although we could not confirm the species in our patient.4

Rickettsiosis usually have a good prognosis, and disease tend to be limited to 10–20 days without sequelae. Complications are usually related to delays in treatment, advanced age and comorbidities. There is also a “malignant” rickettsial form of the disease characterized by multi-organic failure, especially kidney failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation with purpuric exanthema, severe hepatic injury, pulmonary infiltrates and altered consciousnes.5,6

The basis of diagnosis is serology, being limited by cross reactions between members of the group of spotted fevers and those of the typhus group, leading to false positive results.6 Indirect immunofluorescence is the most sensitive and specific of all serological tests. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can also be performed in a eschar biopsy or blood sample and has the advantages of high specificity and being positive in the acute phase of disease.7

Between rickettsial species, Rickettsia conorii and Rickettsia sibirica mongolitimonae are the most frequent between May and September. Rickettsia slovaca and Rickettsia rioja are much more frequent in other times of the year and their eschars are commonly located on the scalp.8 Although in the south of Spain the autumns are getting warmer, either Rickettsia slovaca or Rickettsia rioja could be the causative agents of our case report.

Another recently described tick-borne infection that must be included in the differential diagnosis is the one caused by ‘Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis’. It is transmitted by Ixodes ricinus ticks and it causes an inflammatory disease affecting predominantly patients with underlying diseases.9

Some cases of EN labeled as idiopathic might be secondary to Rickettsial infections in endemic regions.2,3,10 Our case reports an uncommon manifestation of a relatively frequent infection in our country. Rickettsiosis could manifest just with fevers and dermatological manifestation like EN, so we suggest performing at least an initial serology and another one two weeks later in every patient presenting this dermatological sign in order to rule out an easy to treat infection.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict interestAll authors declare no conflicts of interest.