After the last global crisis, firms needed to change and adapt better to the environment. In this scenario, knowledge management is the most important strategic resource, and therefore, it is considered critical for improving firm performance.

However, knowledge management processes and the dynamic environment demand new ways of personnel management, especially a break from traditional and rigid forms of working. As a result of these experiments several innovations in work systems, managerial practices, and personnel policies have appeared. This study examines the holistic relationship between knowledge management, flexibility and firm performance in family firms.

The results show that knowledge management has a positive influence on firm performance. Also, flexibility is not significantly related to firm performance. However, flexibility is positive and significantly related to knowledge management. Furthermore, there is no linear relationship between family involvement in ownership and management, and flexibility and knowledge management in the firm.

Tras la última crisis mundial, las empresas tuvieron que realizar cambios y adaptarse mejor al entorno. En este escenario, la gestión del conocimiento es el recurso estratégico más importante y, por lo tanto, se considera crítico para mejorar el desempeño de la empresa.

Sin embargo, los procesos de gestión del conocimiento y el entorno dinámico exigen nuevas formas de gestión del personal, especialmente una ruptura con las formas tradicionales y rígidas de trabajo. Como resultado de estos cambios han aparecido varias innovaciones en los sistemas de trabajo, prácticas de gestión y políticas de personal. Este estudio examina la relación holística entre la gestión del conocimiento, la flexibilidad y el rendimiento de la empresa en las empresas familiares.

Los resultados muestran que la gestión del conocimiento tiene una influencia positiva en el desempeño de la empresa. Además, la flexibilidad no está relacionada significativamente con el rendimiento de la empresa. Sin embargo, la flexibilidad es positiva y significativamente relacionada con la gestión del conocimiento. Además, no existe una relación lineal entre la participación de la familia en la propiedad y la gestión, y la flexibilidad y la gestión del conocimiento en la empresa.

Facing the fast changing industrial environment, the competitive pressure and the low rates of consume, firms needed to develop abilities to respond and adapt better to this dynamic environment (Cheng, 2007). In this scenario, knowledge is regarded as the most important strategic resource in organizations, and therefore, knowledge management process is considered critical for improving organizational performance (Tippins & Sohi, 2003).

However, knowledge management processes and the dynamic environment demand new ways of personnel management, especially a break from traditional and rigid forms of working. Flexible ways of staffing, time organization or internal mobility have become important tools to promote personnel and organizational achievements (Gramm & Schnell, 2001), but also facilitate the movement of knowledge to the required place within a company (Cheng, 2007). New personnel practices enabling enterprises to increase or decrease the number of employees according to the need for manpower. Such practices include, for instance, subcontracting, outsourcing, and use of temporary workers (Abraham & Taylor, 1996; Davis-Blake & Uzzi, 1993; Gramm & Schnell, 2001; Lepak, Takeuchi, & Snell, 2003).

This study examines the relationship between knowledge management, flexibility and firm performance in family firms. These relationships have not been studied holistically in family businesses, although they represent more than the 85% of all businesses in the Iberian Peninsula. Moreover, family firms conjugate features of cooperative stakeholder enterprises, where the role of noneconomic factors in the management of the firm is a key distinguishing feature that separates family firms from other organizational forms (Gomez-Mejia, Cruz, Berrone, & De Castro, 2011). These noneconomic factors could facilitate knowledge management processes as the result of family involvement.

The sample for the study consisted of eight hundred and thirty eight (838) firms from manufacturing and services industries. The main contributions of the paper are as follows: First, we analyze how labor flexibility can become a key element of knowledge management. Second, the study confirms the importance of knowledge management to improve the results. Finally, we analyze how the familiar character affects the practices of knowledge management and flexibility.

This paper is organized as follows: Firstly, we briefly review knowledge management and labor market flexibility and their relationships with firm performance. Then, we review the relationship between knowledge management, labor market flexibility and family involvement. Next, we present the model and the hypotheses that are going to be tested in the last part of this research. Finally, the results, discussion of their implications and future research directions are presented.

The relationship between labor market flexibility, knowledge management and firm performanceFirms must identify, create and continuously manage knowledge (Hitt, Ireland, & Lee, 2000). Knowledge is the most strategically significant resource the firm can possess and on which sustainable competitive advantages can be built (Nonaka, 1994; Simonin, 1999). Some scholars believe that competition is becoming more knowledge-based and that the sources of competitive advantage are shifting to intellectual capabilities from physical assets (Subramaniam & Venkatraman, 1999). Thus, being able to develop, maintain or nurture and exploit competitive advantages depends on the firm's ability to create, diffuse and utilize knowledge throughout the company (Hoopes & Postrel, 1999). In this sense, there is an increasing body of literature (Holsapple & Jones, 2004, 2005) that suggests that knowledge management is positively link to firm performance (Tippins & Sohi, 2003). ThereforeH1A Firm performance will be positively related to knowledge management practices.

Knowledge management processes and the increasing competition in world and domestic markets and rapid technological development has motivated enterprises in several countries to experiment with new ways of organizing work and with new human resource policies (Gulbrandsen, 2005). These tools are important to promote personnel and organizational achievements, but also facilitate the movement of knowledge to the required place within a company (Cheng, 2007). A while number of credible arguments for the use of different employment modes have been presented and related to firm performance (Tsui, Pearce, Porter, & Hite, 1995; Wright & Snell, 1998). Firms may get improved firm performance from a greater use of external employment as a way to improve flexibility to access and utilize human capital (Tsui et al., 1995). With labor market flexibility, firms may regulate the number and/or varieties of skills within their firm to cope with fluctuations in product or service demands (Wright & Snell, 1998). Atkinson (1984) referred to this as a form of numerical flexibility to reflect a firm's ability to fundamentally alter the number of employees working on its behalf. The ability to quickly assemble needed levels and types of human capital would logically be related to the efficiency by which firms utilize their human capital and, as a result, enhanced firm performance (Lepak et al., 2003). Building on these arguments, we expect that:H1B Firm performance will be positively related to labor market flexibility practices.

With a shorter time frame, the use of contract workers or freelance would likely provide firms with greater flexibility to quickly adapt the composition and skill of their human capital to the needs of the firm. Companies that best manage their knowledge can improve and adapt the variety of tasks and responsibilities of the employees in the firm with the use of labor market flexibility. The needs of high employability of employees in the market improve the employee multiskilling and self-direction (Conner & Prahalad, 1996). In contrast to internal full-time employees, external knowledge workers establish a different psychological contract with organizations that explicitly engenders flexibility (Rousseau, 1995) and high perform, the way to get better employability in the market. It can be expected therefore that companies need expertise, or intend to better fit the needs of the company, attend practices market flexibility. It is therefore expected to:H1C Knowledge management will be positively related to labor market flexibility.

A family firm is defined as one in which there is majority family ownership. In family firms, owners adopt decisions unlike those of nonfamily firms (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011). Gómez-Mejía, Haynes, Núñez-Nickel, Jacobson, and Moyano-Fuentes (2007) explain those dissimilarities as family-owners look for utilities in the form of noneconomic aspect in family firms, and summarize these differences under the concept of preserving the socioemotional wealth in the family business. Decision-making in the family business seek to increase or preserve socioemotional wealth (Kalm & Gomez-Mejia, 2016). In order to understand the family's role in supporting the competitiveness of the family firm, it is key to develop an understanding about different family-based attributes of family firms. The most important attribute that distinguish the influence of the family in the business is the family involvement in ownership and management (Astrachan, Klein, & Smyrnios, 2002).

A higher family involvement should have a positive impact on a family's commitment to the firm in terms of the moral obligation to exercise strong influence, recognition of the costs associated with leaving the firm and emotional bonds (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011). When these conditions are present, the family should be more reluctant to relinquish control. At the same time, in firms in which there is a high family involvement, a low degree of control over family members is exercised (Tosi & Gomez-Mejia, 1994) and few responsibilities to them are required by the lack of results of the company (Verbeke & Kano, 2012). In these firms, there are poorly educated family members, so these businesses tend to be disadvantaged in the development of professional capabilities (Verbeke & Kano, 2012), financial resources are more limited, and/or their families are very concerned with the preservation of wealth, being the majority of its assets invested in the business, and thus limit their investments and risks (Carney, 2005).

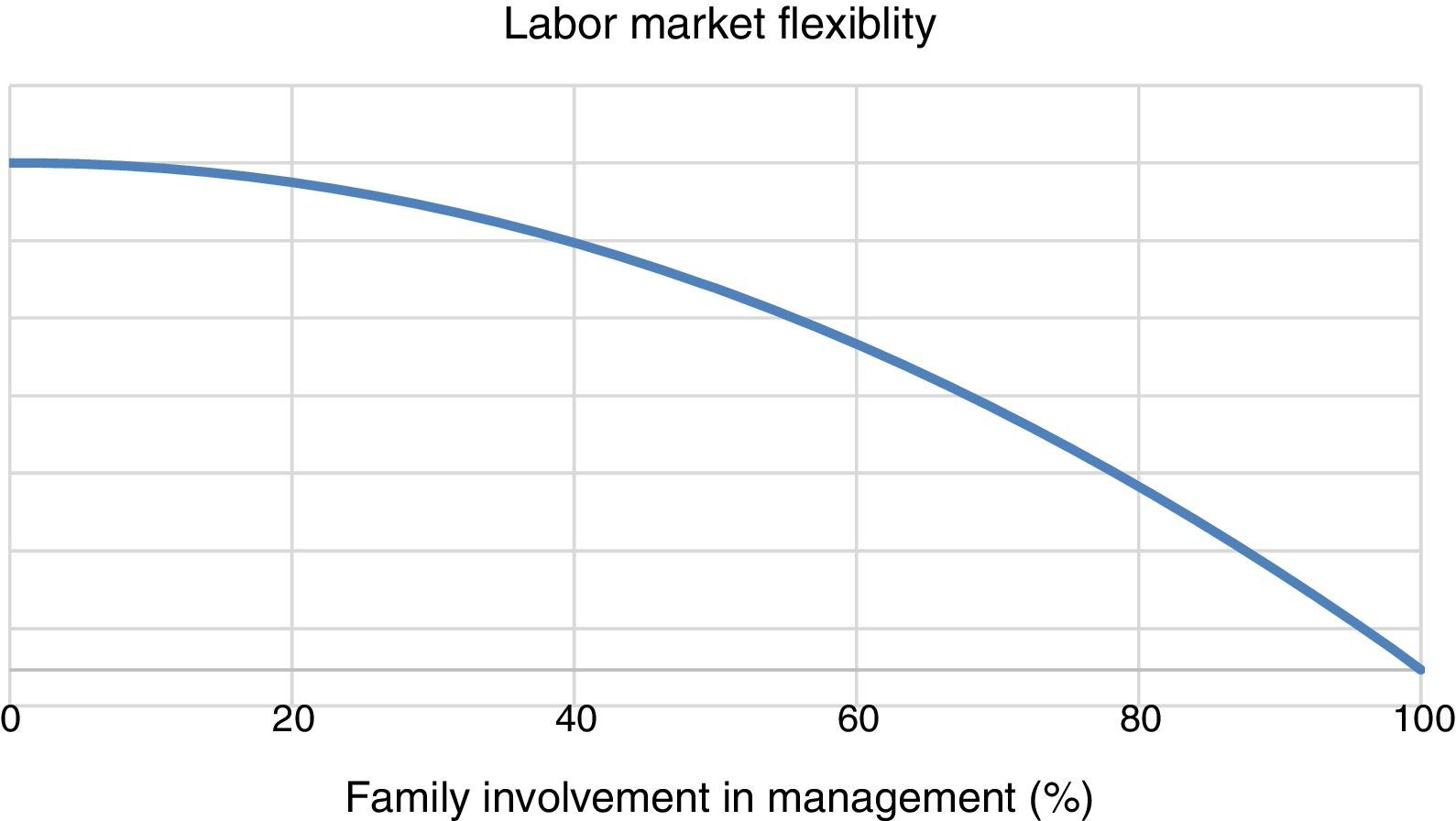

In this sense, labor flexibility is an uncertain and risky process due to lack of information on new and unknown employees, and family businesses tend to have a conservative attitude (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011; Verbeke & Kano, 2012) and be risk averse (Naldi, Nordqvist, Sjöberg, & Wiklund, 2007). Otherwise, families in general, are largely characterized by altruism, loyalty, and trust, even to strangers (Gulbrandsen, 2005). Also, the use of flexibility can reduce firm costs and increase profits. In synthesis, family involvement may have both positive and negative effects on the use of flexibility, so our observations led us to hypothesize a nonlinear relationship between family involvement and labor flexibility (Sciascia & Mazzola, 2008; Sciascia et al., 2012). It is therefore expected to:H2 Labor market flexibility practices will be nonlinear related to family involvement.

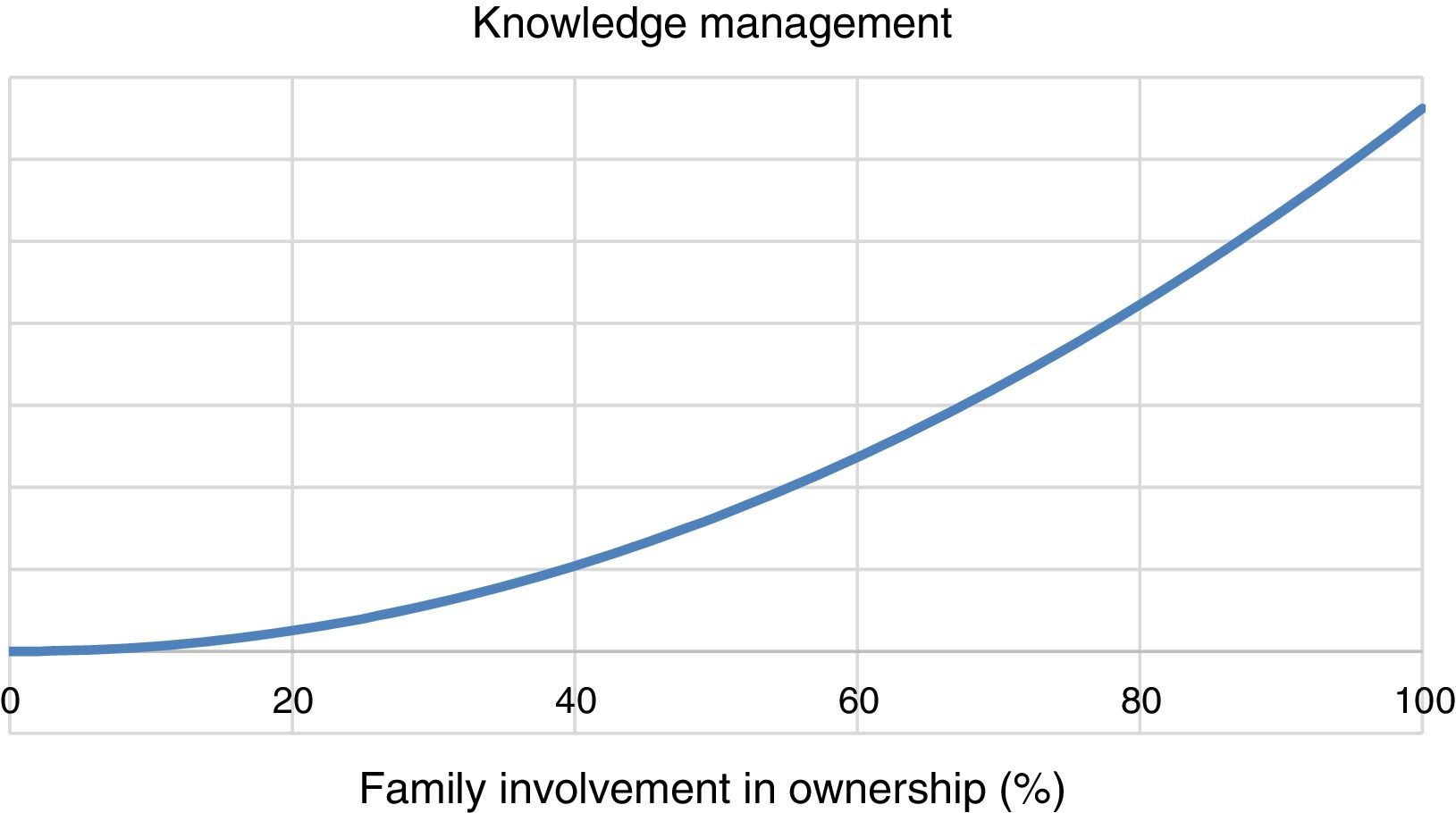

Create knowledge management capabilities requires a large investment in professional capabilities and technological diversification, and usually forces the family to establish associations, or lease of the property to third parties outside the company, such as venture capital or institutional investors. The concern of the family that owns the business to control partner opportunism reduces the company's ability to respond effectively to environmental changes or to take advantage of market opportunities that arise (Zahra, Hayton, & Salvato, 2004; Zahra, Neubaum, & Larrañeta, 2007). We expected the form of the relationship between knowledge management practices and family involvement to be nonlinear. At high levels of family involvement, increasing knowledge management practices promote higher improvement in knowledge management capabilities that in low levels of family involvement. The upper limits of knowledge management practices that can reasonably be achieved through the deliberate actions of managers will do little to enhance knowledge management capabilities in family businesses professionalized. It is therefore expected to:H3 Knowledge management practices will be nonlinear related to family involvement.

Our sample was drawn from the SABI database and used single-informants. The population is composed of Spanish companies in the sectors of industry and services with more than 15 employees located in the southeast of Spain, and consists of a total of 1751 companies that may or may not be family companies. In Spain, there is no database that identifies-family businesses and non-family business, the family business study in Spain 2015 (Instituto de Empresa Familiar & Red de Catedras de Empresa Familiar, 2016) shows that the number of family businesses in the south-east of Spain is greater than 90% and greater to others localization of Spain. Also, the proportion of family businesses is greater in the sectors of industry, trade, transport and hospitality (Instituto de Empresa Familiar & Red de Catedras de Empresa Familiar, 2016), sectors used in this study. The use of this geographical area and these sectors is due to the importance of the family business there.

The information was collected by personal interview with the top executive of the company, using a structured questionnaire and directed to all companies belonging to the population. We have tested for common methods variance (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003) which is a potential danger arising from the use of a single informant when collecting data in each firm, and suggest that the absence of a unique factor with an eigenvalue greater than one indicates that this source of error is not significant. The presence of an interviewer increased the cooperation rates and facilitated immediate clarification. In order to collect high-quality data, the interviewers were trained in order to familiarize them with the variety of situations likely to be encountered, as well as the concepts, definitions, and procedures involved.

Eight hundred and thirty eight questionnaires were obtained for family firms, yielding a response rate of 48.71%. To identify family firms, the CEO has been asked their perception of whether or not they are family businesses, as well as previous studies (Hall, Melin, & Nordqvist, 2001; Westhead & Cowling, 1998). This has identified the sample of 838 family businesses. Approximately 57.9% of responses came from manufacturing firms and the rest from the service sector. The sample was composed of companies of different sizes and many of these companies engage in international activity.

The respondent companies were compared with non-respondents on variables such as size and company performance. No statistically significant differences were found between the means of these variables at the 0.01 level in the two groups, suggesting no response bias (F=0.375, p>0.1). Overall, although these variables are frequently used, we cannot be certain that the respondents are not unrepresentative of the population on some other variables.

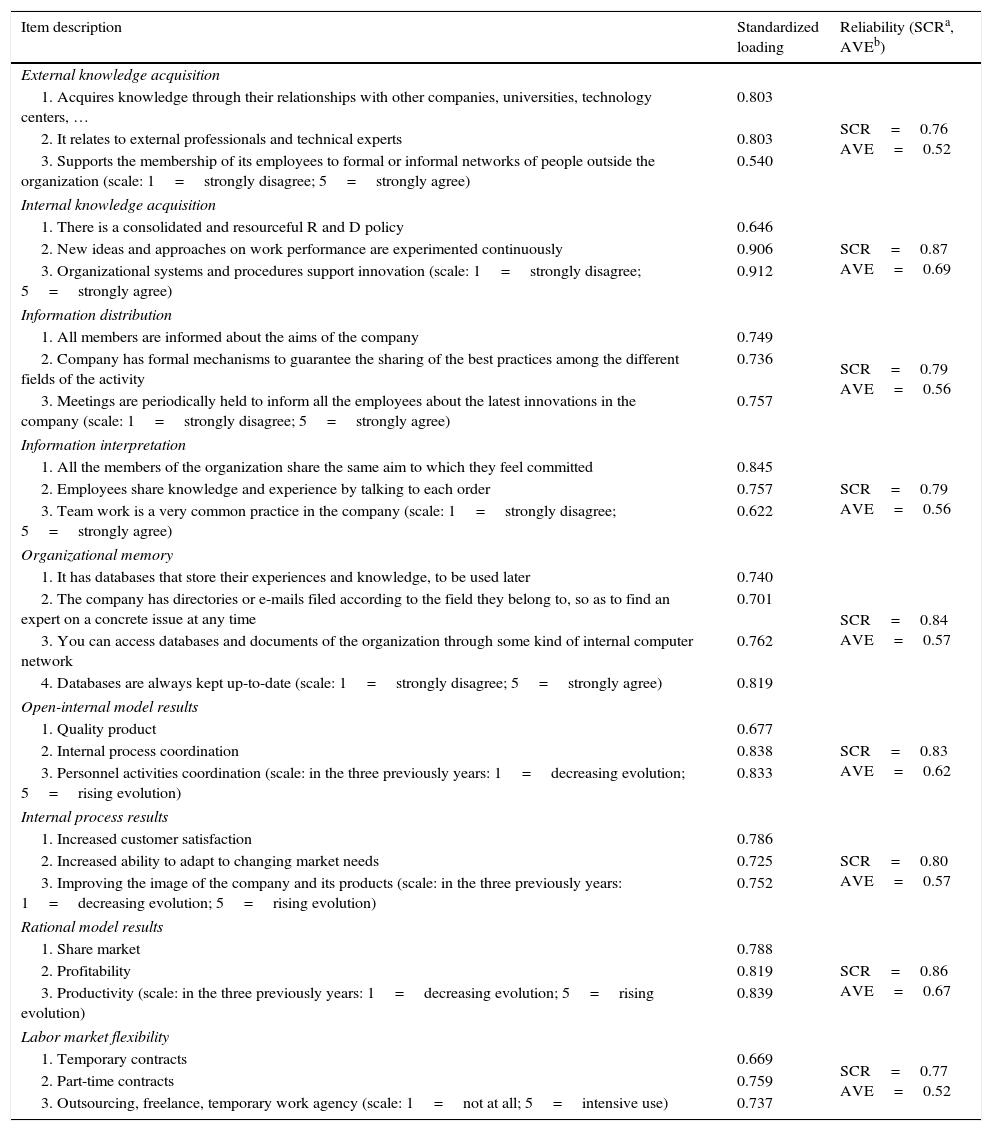

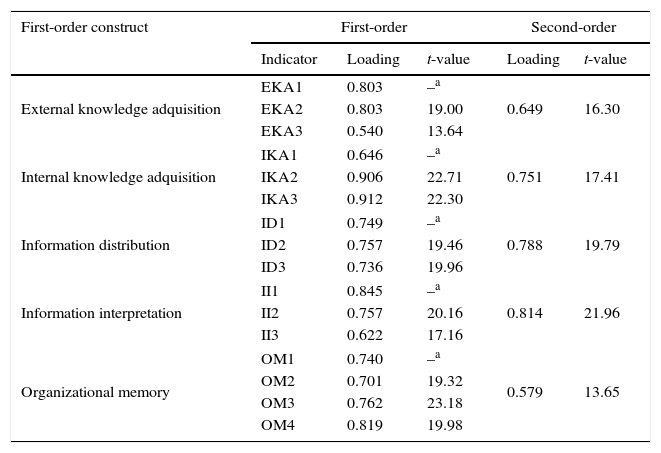

Measures and measurement propertiesKnowledge management. We have used the knowledge management scale from the study of Pérez López, Manuel Montes Peón, and José Vázquez Ordás (2004). The measures of these variables are displayed for every dimension of knowledge management (see Table 1): external knowledge acquisition (scale composite reliability ρc SCR=0.76, average variance extracted ρc AVE=0.52), internal knowledge adquisition (scale composite reliability ρc SCR=0.87, average variance extracted ρc AVE=0.69), information distribution (ρc SCR=0.79, ρc AVE=0.56), information interpretation (ρc SCR=0.79, ρc AVE=0.56) and organizational memory (ρc SCR=0.84, ρc AVE=0.58). These dimensions are considered to be a single construct made up of the five knowledge management dimensions.

Constructs measurements summary: confirmatory factor analysis and scale reliability.

| Item description | Standardized loading | Reliability (SCRa, AVEb) |

|---|---|---|

| External knowledge acquisition | ||

| 1. Acquires knowledge through their relationships with other companies, universities, technology centers, … | 0.803 | SCR=0.76 AVE=0.52 |

| 2. It relates to external professionals and technical experts | 0.803 | |

| 3. Supports the membership of its employees to formal or informal networks of people outside the organization (scale: 1=strongly disagree; 5=strongly agree) | 0.540 | |

| Internal knowledge acquisition | ||

| 1. There is a consolidated and resourceful R and D policy | 0.646 | SCR=0.87 AVE=0.69 |

| 2. New ideas and approaches on work performance are experimented continuously | 0.906 | |

| 3. Organizational systems and procedures support innovation (scale: 1=strongly disagree; 5=strongly agree) | 0.912 | |

| Information distribution | ||

| 1. All members are informed about the aims of the company | 0.749 | SCR=0.79 AVE=0.56 |

| 2. Company has formal mechanisms to guarantee the sharing of the best practices among the different fields of the activity | 0.736 | |

| 3. Meetings are periodically held to inform all the employees about the latest innovations in the company (scale: 1=strongly disagree; 5=strongly agree) | 0.757 | |

| Information interpretation | ||

| 1. All the members of the organization share the same aim to which they feel committed | 0.845 | SCR=0.79 AVE=0.56 |

| 2. Employees share knowledge and experience by talking to each order | 0.757 | |

| 3. Team work is a very common practice in the company (scale: 1=strongly disagree; 5=strongly agree) | 0.622 | |

| Organizational memory | ||

| 1. It has databases that store their experiences and knowledge, to be used later | 0.740 | SCR=0.84 AVE=0.57 |

| 2. The company has directories or e-mails filed according to the field they belong to, so as to find an expert on a concrete issue at any time | 0.701 | |

| 3. You can access databases and documents of the organization through some kind of internal computer network | 0.762 | |

| 4. Databases are always kept up-to-date (scale: 1=strongly disagree; 5=strongly agree) | 0.819 | |

| Open-internal model results | ||

| 1. Quality product | 0.677 | SCR=0.83 AVE=0.62 |

| 2. Internal process coordination | 0.838 | |

| 3. Personnel activities coordination (scale: in the three previously years: 1=decreasing evolution; 5=rising evolution) | 0.833 | |

| Internal process results | ||

| 1. Increased customer satisfaction | 0.786 | SCR=0.80 AVE=0.57 |

| 2. Increased ability to adapt to changing market needs | 0.725 | |

| 3. Improving the image of the company and its products (scale: in the three previously years: 1=decreasing evolution; 5=rising evolution) | 0.752 | |

| Rational model results | ||

| 1. Share market | 0.788 | SCR=0.86 AVE=0.67 |

| 2. Profitability | 0.819 | |

| 3. Productivity (scale: in the three previously years: 1=decreasing evolution; 5=rising evolution) | 0.839 | |

| Labor market flexibility | ||

| 1. Temporary contracts | 0.669 | SCR=0.77 AVE=0.52 |

| 2. Part-time contracts | 0.759 | |

| 3. Outsourcing, freelance, temporary work agency (scale: 1=not at all; 5=intensive use) | 0.737 | |

Fit statistics for measurement model of 28 indicators for nine constructs: χ2(314)=682.32; p<0.001; NFI=0.93; NNFI=0.95; CFI=0.96; IFI=0.96; RMSEA=0.04.

A second-order factor analysis is conducted to demonstrate that the knowledge management dimensions can be modeled by a higher order construct in order to analyze our data (Table 2). We estimated this model using EQS 6.1. The results suggest a good fit of the second-order specification for our measure of knowledge management (χ2=336.65, df=113, p<0.001; Bentler–Bonett normed fit index [NFI]=0.94; Bentler–Bonett non-normed fit index [NNFI]=0.95; incremental fit index [IFI]=0.96; comparative fit index [CFI]=0.96; root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA]=0.05). The NFI, NNFI, IFI and CFI statistics exceed the recommended 0.90 threshold level (Hoyle, 1995). Furthermore, the RMSEA is below 0.080. Although a significant chi-square value indicates that the model is an inadequate fit, the sensitivity of this test to sample size confounds this finding and makes rejection of the model on the basis of this evidence alone inappropriate (Bagozzi, 1980). However, a ratio less than three (χ2/df<3) indicates a good fit for the hypothesized model (Joreskög, 1978). Therefore, it is possible to conclude that these dimensions can be modeled by a second-order construct.

Second-order confirmatory factor analysis of knowledge management.

| First-order construct | First-order | Second-order | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Loading | t-value | Loading | t-value | |

| External knowledge adquisition | EKA1 | 0.803 | –a | 0.649 | 16.30 |

| EKA2 | 0.803 | 19.00 | |||

| EKA3 | 0.540 | 13.64 | |||

| Internal knowledge adquisition | IKA1 | 0.646 | –a | 0.751 | 17.41 |

| IKA2 | 0.906 | 22.71 | |||

| IKA3 | 0.912 | 22.30 | |||

| Information distribution | ID1 | 0.749 | –a | 0.788 | 19.79 |

| ID2 | 0.757 | 19.46 | |||

| ID3 | 0.736 | 19.96 | |||

| Information interpretation | II1 | 0.845 | –a | 0.814 | 21.96 |

| II2 | 0.757 | 20.16 | |||

| II3 | 0.622 | 17.16 | |||

| Organizational memory | OM1 | 0.740 | –a | 0.579 | 13.65 |

| OM2 | 0.701 | 19.32 | |||

| OM3 | 0.762 | 23.18 | |||

| OM4 | 0.819 | 19.98 | |||

Fit statistics for measurement model of 12 indicators for four constructs: χ2 (113)=336.65; p<0.001; NFI=0.94; NNFI=0.95; IFI=0.96; CFI=0.96; RMSEA=0.05.

Labor market flexibility. The labor flexibility (scale composite reliability ρc SCR=0.77, average variance extracted ρc AVE=0.53) is measured from the major options offered by the latest reform of the labor market in Spain, the direct hiring of employees through temporary contracts or part-time contracts, and through indirect contracting (outsourcing, freelance, temporary work agency).

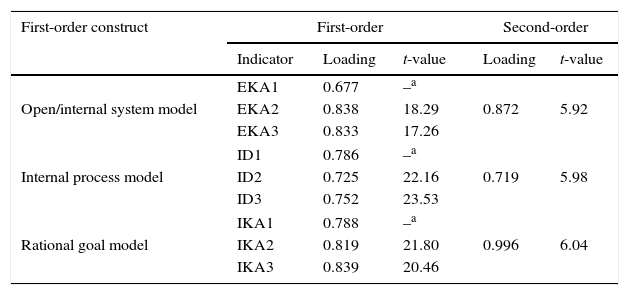

Firm performance. In order to measure the impact of knowledge management and labor market flexibility on company performance, self-explanatory measures of performance, such as change in market share, new product success, growth, profitability, etc. are usually employed, because, as has been shown in previous tests, subjective and objective measures of performance are highly correlated. Furthermore, the literature defends the use of non-financial performance measures alone (Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1983). So, the measures of these variables are taken from Quinn and Rohrbaugh (1983), who suggest that the criteria for organizational effectiveness can be sorted to different value dimensions. These dimensions make the identification of four basic models of organizational effectiveness possible: the human relations model, the internal process model, the open system model and the rational goal model. The preliminary exploratory analysis and the confirmatory factor analysis (Table 1) suggest that only three of these models are useful in the present study: the open/internal system model (ρc SCR=0.80, ρc AVE=0.57), the rational goal model (ρc SCR=0.86, ρc AVE=0.67) and the internal process model (ρc SCR=0.83, ρc AVE=0.62). With the aim of analyzing company results, another second order construct has been constructed (see Table 3).

Second-order confirmatory factor analysis of firm performance.

| First-order construct | First-order | Second-order | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Loading | t-value | Loading | t-value | |

| Open/internal system model | EKA1 | 0.677 | –a | 0.872 | 5.92 |

| EKA2 | 0.838 | 18.29 | |||

| EKA3 | 0.833 | 17.26 | |||

| Internal process model | ID1 | 0.786 | –a | 0.719 | 5.98 |

| ID2 | 0.725 | 22.16 | |||

| ID3 | 0.752 | 23.53 | |||

| Rational goal model | IKA1 | 0.788 | –a | 0.996 | 6.04 |

| IKA2 | 0.819 | 21.80 | |||

| IKA3 | 0.839 | 20.46 | |||

Fit statistics for measurement model of 12 indicators for four constructs: χ2 (23)=62.29; p<0.001; NFI=0.97; NNFI=0.97; IFI=0.98; CFI=0.98; RMSEA=0.05.

The results suggest a good fit of the second-order specification (χ2=62.29, df=23, p=0.001; NFI=0.97; NNFI=0.97; CFI=0.98; IFI=0.98; RMSEA=0.04). All, GFI, CFI, TLI and IFI exceed the recommended 0.90 threshold level (Hoyle, 1995). The RMSEA is below 0.050. Although a significant chi-square value indicates that the model is an inadequate fit, the sensitivity of this test to sample size confounds this finding and makes rejection of the model on the basis of this evidence alone inappropriate (Bagozzi, 1980). However, a ratio less than three (χ2/df<3) indicates a good fit for the hypothesized model (Joreskög, 1978). Therefore, it is possible to conclude that the three result dimensions can be modeled by a second-order construct.

Family involvement in ownership (FIO) and family involvement in management (FIM). FIO was measured using the percentage of the firm's equity held by the owning family (Sciascia & Mazzola, 2008). FIM was measured using the percentage of a firm's managers who were also family members in 2000 (Sciascia & Mazzola, 2008). The average value of FIO in our sample is 66.99%, while the average value of FIM is 56.31%.

Control variables: Firm age, firm size and economic activity. Firm age was measured by the number of years the firm has been in existence, whereas firm size was measured by the number of full-time employees. The average company age in our sample is 20.30 years, with a standard deviation of 15.55. The average number of employees is 58.18, with a standard deviation of 152.78. Thus, for kurtosis considerations and following Sciascia and Mazzola (2008), the two variables were measured respectively by the logarithm of the number of years the firm has been in existence and by the logarithm of the number of full-time employees. We controlled also for economic activity using dummy coding: manufacturing firms were coded 1 and other firms in the sample were coded 0.

To assess the unidimensionality of each construct (Table 1), a confirmatory factor analysis of the nine constructs employing 28 items was conducted (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). The measurement model provides a reasonable fit to the data (χ2=682.31, df=314, p<0.001; NFI=0.93; NNFI=0.95; CFI=0.96; IFI=0.96; RMSEA=0.04). The traditionally reported fit indices are within the acceptable range. Reliability of the measures is calculated with Bagozzi and Yi's (1988) composite reliability index and with Fornell and Larcker's (1981) average variance extracted index. For all the measures, both indices are higher than the evaluation criteria of 0.6 for the composite reliability and 0.5 for the average variance extracted (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988). Furthermore, all items load on their hypothesized factors (see Table 1), and the estimates are positive and significant (the lowest t-value is 11.60), which provides evidence of convergent validity (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988).

Discriminant validity was tested using three different procedures recommended by Anderson and Gerbing (1988) and Fornell and Larcker (1981). First, discriminant validity is indicated since the confidence interval (±2 S.E.) around the correlation estimate between any two latent indicators never includes 1.0 (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). Second, discriminant validity was tested by comparing the square root of the AVEs for a particular construct to its correlations with the other constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Finally, we compared the chi-square statistic between the constrained model where the correlation of a pair of factors was fixed to unity and the unconstrained model with the correlation freely estimated (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). The results of these three test provided strong evidence of discriminant validity among the constructs.

After the confirmatory factor analysis has been performed to get a rigorous analysis of the measurement model (see Tables 1–3), the hypotheses were tested by running regression analyses.

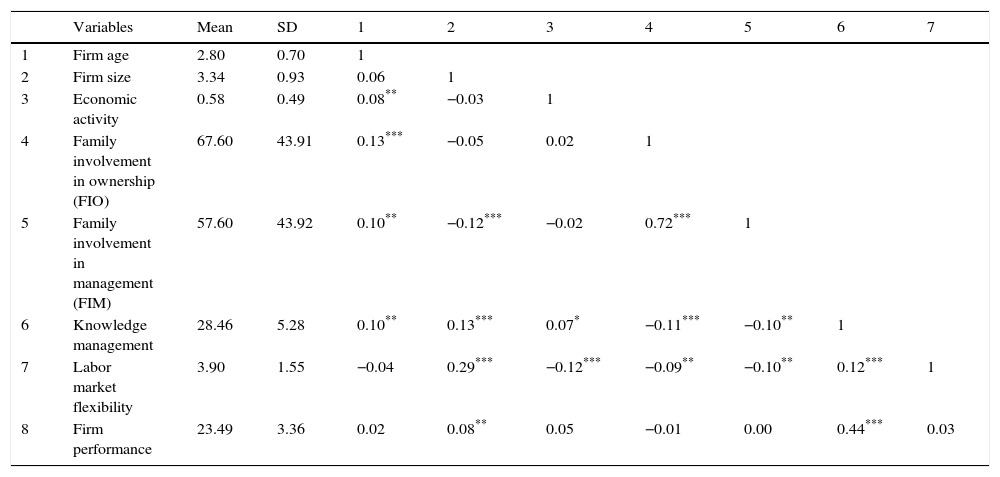

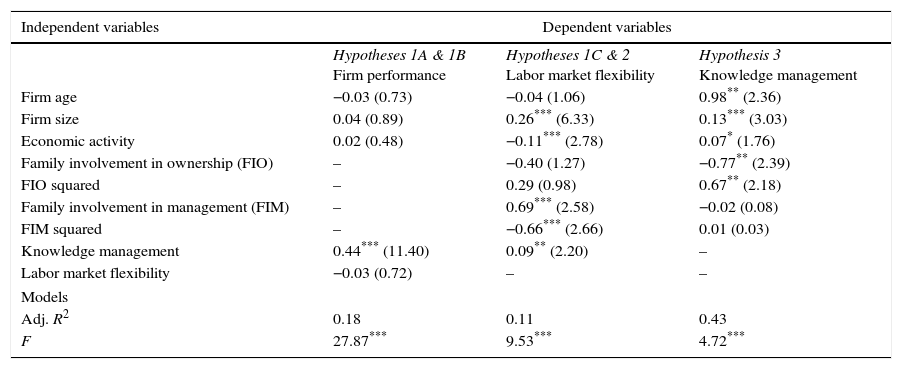

Analysis and resultsThe regression model provides a suitable tool to examine nonlinear relations between variables, or when the phenomenon under study has a behavior that can be considered as parabolic (Hair, Anderson, Black, & Babin, 2016). The use of regression analysis has been used by other previous research (Sciascia & Mazzola, 2008; Sciascia et al., 2012, among others) in family firms to examine the quadratic relations. Table 4 presents the correlations between variables and Table 5 shows the regression results for firm performance, knowledge management and labor market flexibility.

Means, standard deviation and correlation analysis.

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Firm age | 2.80 | 0.70 | 1 | ||||||

| 2 | Firm size | 3.34 | 0.93 | 0.06 | 1 | |||||

| 3 | Economic activity | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.08** | −0.03 | 1 | ||||

| 4 | Family involvement in ownership (FIO) | 67.60 | 43.91 | 0.13*** | −0.05 | 0.02 | 1 | |||

| 5 | Family involvement in management (FIM) | 57.60 | 43.92 | 0.10** | −0.12*** | −0.02 | 0.72*** | 1 | ||

| 6 | Knowledge management | 28.46 | 5.28 | 0.10** | 0.13*** | 0.07* | −0.11*** | −0.10** | 1 | |

| 7 | Labor market flexibility | 3.90 | 1.55 | −0.04 | 0.29*** | −0.12*** | −0.09** | −0.10** | 0.12*** | 1 |

| 8 | Firm performance | 23.49 | 3.36 | 0.02 | 0.08** | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.44*** | 0.03 |

Regression analysis.

| Independent variables | Dependent variables | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypotheses 1A & 1B Firm performance | Hypotheses 1C & 2 Labor market flexibility | Hypothesis 3 Knowledge management | |

| Firm age | −0.03 (0.73) | −0.04 (1.06) | 0.98** (2.36) |

| Firm size | 0.04 (0.89) | 0.26*** (6.33) | 0.13*** (3.03) |

| Economic activity | 0.02 (0.48) | −0.11*** (2.78) | 0.07* (1.76) |

| Family involvement in ownership (FIO) | – | −0.40 (1.27) | −0.77** (2.39) |

| FIO squared | – | 0.29 (0.98) | 0.67** (2.18) |

| Family involvement in management (FIM) | – | 0.69*** (2.58) | −0.02 (0.08) |

| FIM squared | – | −0.66*** (2.66) | 0.01 (0.03) |

| Knowledge management | 0.44*** (11.40) | 0.09** (2.20) | – |

| Labor market flexibility | −0.03 (0.72) | – | – |

| Models | |||

| Adj. R2 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.43 |

| F | 27.87*** | 9.53*** | 4.72*** |

Each model, apart from control variables, includes those variables necessary to test hypotheses. To test Hypothesis 1A and Hypothesis 1B, we introduced control variables, knowledge management and labor market flexibility as independent variables and firm performance as dependent variable (Table 5). We obtained that firm performance is only positively and significantly related to knowledge management. Thus, Hypothesis 1A was supported and Hypothesis 1B was not supported. Our data cannot confirm the existence of any relationship between labor market flexibility and firm performance.

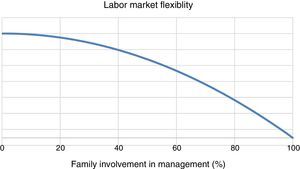

To test Hypothesis 1C and Hypothesis 2, we introduced control variables, FIO, FIO SQUARED, FIM, FIM squared and knowledge management as independent variables and labor market flexibility as dependent variable (Table 5). We obtained that labor market flexibility is positively and significantly related to firm size, service activities and knowledge management, but only family involvement in management is significantly related to labor market flexibility. Our data cannot confirm the existence of any relationship between family involvement in ownership and labor market flexibility. Thus, Hypothesis 1C was supported and Hypothesis 2 was partially supported, our data show the existence of a nonlinear relationship between FIM and labor market flexibility. This means that labor market flexibility decreases as FIM increases, and the decrease is more noticeable at lower levels of FIM (Fig. 1).

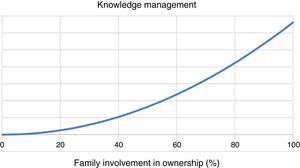

To test Hypothesis 3, we introduced control variables, FIO, FIO SQUARED, FIM and FIM squared as independent variables and knowledge management as dependent variable (Table 5). We obtained that knowledge management is positively and significantly related to firm age, firm size and manufacturing activities, but only family involvement in ownership is significantly related to knowledge management. Our data cannot confirm the existence of any relationship between family involvement in management and knowledge management. Thus, even Hypothesis 3 was partially supported, our data show the existence of a nonlinear relationship between FIO and knowledge management. This means that knowledge management increases as FIO increases, and the increase is more noticeable at higher levels of FIO (Fig. 2).

ConclusionsThe relationship between knowledge management, flexibility and firm performance has been discussed by several studies previously. There are no holistic models that have referred to the above relationships, nor examining the effect of family within the company. No previous work has analyzed the effect of family involvement in ownership and management, and examined its influence on knowledge management and flexibility.

The results show that there is a positive effect of knowledge management on firm performance. Our results are consistent with the assertions of Holsapple and Jones (2004, 2005). They support that knowledge is the most strategically resource the firm can posses and on which sustainable competitive advantages can be built. Furthermore, our findings show that there is not a positive relationship between labor market flexibility and firm performance. Our findings do not support the evidence from previous studies (Lepak et al., 2003; Tsui et al., 1995) that argue firms may get improved firm performance from a greater use of external employment.

On the other hand, it has been found that knowledge management is an important resource that can positively influence the labor market flexibility practices. Companies that best manage their knowledge can improve and adapt the variety of tasks and responsibilities of the employees in the firm with the use of labor market flexibility. The needs of high employability of employees in the market improve the employee multiskilling and self-direction (Conner & Prahalad, 1996).

The results show that the influence of the family can be positive or negative, and the existence of nonlinear relationship as previous studies suggest (Sciascia & Mazzola, 2008; Sciascia et al., 2012). In this sense, our data show the existence of a nonlinear relationship between family involvement in management and labor market flexibility. This means that labor market flexibility decreases as family involvement in management increases, and the decrease is more noticeable at lower levels of family involvement in management. Also, the results show the existence of a nonlinear relationship between family involvement in ownership and knowledge management. This means that knowledge management increases as family involvement in ownership increases, and the increase is more noticeable at higher levels of family involvement in ownership.

From a practical level, when family involvement increases in corporate ownership, the firm identify, create and manage better knowledge. The family owners understand that knowledge is a strategic resource for the business and its development and exploitation is necessary to develop competitive advantages that protect and sustain the socioemotional wealth of the family business. In addition, socioemotional wealth management, understood as a set of knowledge aspects introduced by the family in the company, is possible as long as the company knows how to manage existing knowledge within the family business. Also, the family firms that better manage their knowledge, in order to preserve and improve their socioemotional wealth, obtain better firm performance.

Nevertheless, this study has some limitations. First, the survey used single informants as primary source of information. Although the use of single informants is usual in most studies, multiple informants would enhance the validity of the research findings. In order to get round this limitation, analyses have tested the absence of potential for common methods variance caused by collecting data from a single informant in each firm. The results have confirmed the lack of a unique factor with eigenvalue greater than one (Podsakoff et al., 2003). A second limitation is the problem of heterogeneity of the sample that may affect to the extracted conclusions. A third limitation is the cross-sectional design of this research. Thus, researchers should interpret with caution the causality between the constructs (Tippins & Sohi, 2003). Future research should use longitudinal studies, structural equation model analysis, and the inclusion of others individual characteristics of the family businesses.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.