The study aims to compare individuals diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and healthy individuals in terms of psychosis-like experiences (PLEs) and investigate the relationship between PLEs and OCD severity.

MethodsSociodemographic information form, Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS), the positive dimension of Community Assessment of Psychic Experiences (CAPE-P), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), and Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) were applied to 83 OCD patients and 83 healthy individuals. The 11th item of Y-BOCS (Y-BOCS-11) was used to evaluate the level of insight. The OCD group was compared with the healthy control group in terms of sociodemographic information and CAPE-P score. In the OCD group, mediation analyses were performed to evaluate the factors affecting the relationship between OCD severity and PLEs.

ResultsThe OCD group had higher CAPE-P scores than the healthy control group. CAPE-P scores were weakly correlated with Y-BOCS-11 and Y-BOCS total scores. It was found that the relationship between OCD severity and PLEs was mediated by poor insight; however, the scores of depression and anxiety did not.

ConclusionThe results show that the level of insight is a determinative factor for PLEs in OCD. The fact that PLEs are common in the OCD group and healthy individuals support the concept of the psychosis continuum. We emphasize that being aware of PLEs in OCD can provide new understandings of the phenomenon of OCD and psychosis.

Recent studies have shown that psychotic symptoms are present not only in schizophrenia spectrum disorders but also in nonclinical samples. Psychotic phenomena are considered to be variations that occur along a continuum.1-3 Subthreshold forms of psychotic experiences, such as perceptual abnormalities, delusional or magical thoughts, that do not reach the clinical level, regardless of their apparent severity, are defined as psychotic-like experiences (PLEs).4,5 The frequency of PLEs detected in the general population differs according to the instrument used.6,7

PLEs generally share common risk factors with schizophrenia such as neurocognitive deficits,8,9 cannabis use10 and stress.11,12 In addition, common neurobiological and functional imaging findings have been reported.13-18 PLEs share many sociodemographic characteristics with schizophrenia, such as young age, unemployment, being a migrant, and male gender.19-21 Recent changes to the DSM have emphasized the psychosis continuum, and the "attenuated psychosis syndrome" has been included in the DSM for further research.22 In addition, individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis with mild/transient psychotic symptoms are included in the psychosis continuum.23

PLEs also occur in a number of other psychiatric disorders, including anxiety disorders,24 depression25 and OCD.26 There are conceptual differences between delusions and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Delusions are conceptualized as highly believed, inconsistent with reality, egosyntonic, lacking insight, and obsessions as thoughts, images, and impulses that are intrusive and have a degree of insight.22 Although obsessions, overvalued thoughts and delusions differ in some respects,27 it is suggested that obsessions and overvalued thoughts may predispose the person to the onset of delusions.28 Longitudinal studies have found that both the OCD phenotype is associated with the development of future clinical and subclinical psychosis, and the extended psychosis phenotype is associated with the development of OCD in the future.29,30

There is overlap between OCD and schizophrenia in terms of some functional and structural brain abnormalities, neurotransmitter systems, clinical and sociodemographic characteristics (e.g. being an ethnic minority).31 Environmental factors such as perinatal traumas, childhood traumas, and substance use pose a risk for both OCD and psychosis.32-36 In both disorders, there are common neurocognitive impairments,37 and functional and structural impairments in the basal ganglia, dopaminergic dysregulation, and prefrontal cortex volume changes.38,39 Similar long-term verbal and visual memory performances were found in OCD patients with poor insight and schizophrenia patients.31 Matsunaga et al.40 found that OCD patients with poor insight and patients with OCD and schizophrenia co-diagnosed had similar functional loss, schizotypal personality disorder was common in OCD patients with poor insight, and both groups were similar in terms of early-onset OCD, longer disease duration, and being single. 10–20% of first-episode psychoses initially have obsessive-compulsive symptoms.41,42 Obsessive-compulsive symptom rates are also higher in the high-risk group for psychosis compared to the healthy population.43 There is a study that reported the prevalence of musical hallucinations in OCD patients at a rate of 41%.44

Although the relationship between OCD and psychosis is well known, PLEs in OCD remain an underexplored topic. In a study, OCD and schizophrenia groups scored higher on positive, negative, and depression dimensions of psychosis than healthy controls.45 Bortolon and Raffard46 found that OCD and schizophrenia patients experienced more PLEs than healthy controls, and that the OCD and schizophrenia groups were largely similar in terms of PLEs.

In psychiatry practice, insight is conceptualized as the acknowledgement that one has a mental illness and that their unusual experiences are pathological.47,48 Nevertheless, it has been argued that a dichotomous distinction between obsessive-compulsive thoughts and lack of insight cannot be made and that these beliefs are a continuity. The idea of egodystonia has been changed, and it has been stated that obsessions, overvalued thoughts and delusions can take place in a spectrum.27,49 Therefore, in DSM 5, the level of insight is classified as good/fair, poor, and absent (delusional).22 It has been reported that the possibility of psychotic disorder is more common in patients with poor insight.50 The role of insight, which is part of reality testing, in the relationship between OCD and PLEs is not yet clear.

ObjectivesThis study aimed to compare individuals with OCD and healthy controls in terms of psychosis-like experiences, examine the relationship between psychosis-like experiences and OCD severity, and examine the role of insight, anxiety and depression levels in this relationship.

MethodsParticipantsPatients who applied to Samsun Ondokuz Mayıs University Medical Faculty Department of Psychiatry, Turkey, diagnosed with OCD according to DSM-5 constituted the patient group. Healthy volunteers with sociodemographic characteristics similar to the patient group were included in the control group. Those outside the age range of 18–65, those with comorbid psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, mental retardation, autism, dementia, organic state-related mental disorder, alcohol and substance use disorder (except for tobacco use), those with a medical condition that prevents them from understanding the scales given, and those who have immigrated to Turkey from another country in the last five years have been excluded. Both the patient group and the control group consisted of 83 individuals.

The individuals participating in the research were informed about it, and their written consent was obtained. Approval for the research was obtained from the Ondokuz Mayıs University Clinical Research Ethics Committee with decision number 2020/706. The research data were collected between December 2020 and December 2021.

MeasuresThe sociodemographic data form specially prepared by the researchers was used to determine the sociodemographic information, socioeconomic situation, duration of the disorder, psychiatric and treatment history, family history, and physical conditions of the participants. The "monthly income" variable, which reflects the economic situation, was obtained by dividing the total monthly income in the participants' residences by the number of people living in the same residence.

The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) was used to determine the level of depression. The highest total score of 52 is obtained from the scale.51

The Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) was used to determine the level of anxiety. The highest total score of 56 is obtained from the scale.52

The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) was developed by Goodman et al. to measure the type and severity of obsessive-compulsive symptoms. While evaluating the 19-item scale, only the first 10 items are included in the scoring (5 questions for obsession, 5 questions for compulsion). Each item is scored from 0 to 4 points. The total score of the obsession dimension can vary between 0 and 20, the total score of the compulsion dimension can vary between 0 and 20, and the total score of the scale can vary between 0 and 40 points. The 11th item of the scale measures the level of insight. In the insight item, "excellent insight" is scored 0 points, "good insight" 1 point, "moderate insight" 2 points, "poor insight" 3 points, and "insight lost" 4 points. As the score increases, it reflects the impairment in insight.53

The Community Assessment of Psychic Experience (CAPE) has been developed to measure the positive, negative and depression dimensions of psychosis in the general population. There are 42 items in the scale, 20 for positive psychotic experiences, 14 for negative symptoms, and 8 for depressive symptoms. Positive dimension scores for PLEs are taken into account. While answering the scale, the frequency of the experiences and the distress they create are scored.54 Responses “never” and “sometimes” are recoded as 0, “often” and “almost constantly” as 1 to calculate the extent of symptoms.55 The positive dimension of CAPE (CAPE-P) was used in the study.

Statistical analysisStatistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 22 package program. The skewness and kurtosis values were checked to see if the groups were normally distributed. As suggested by Tabachnick and Fidell56 the data were considered to be normally distributed if the skewness and kurtosis values were between −1.5 and +1.5. The data that were not normally distributed were made suitable for the normal distribution by applying statistical transformation. Chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables, Student's-t-test was used to compare normally distributed continuous variables, and Mann Whitney-U test was used to compare continuous variables that were not normally distributed despite statistical transformation between two groups. Pearson correlation analysis was used in the correlation analysis of normally distributed variables, and Spearman correlation analysis was used in the correlation analysis of non-normally distributed variables.

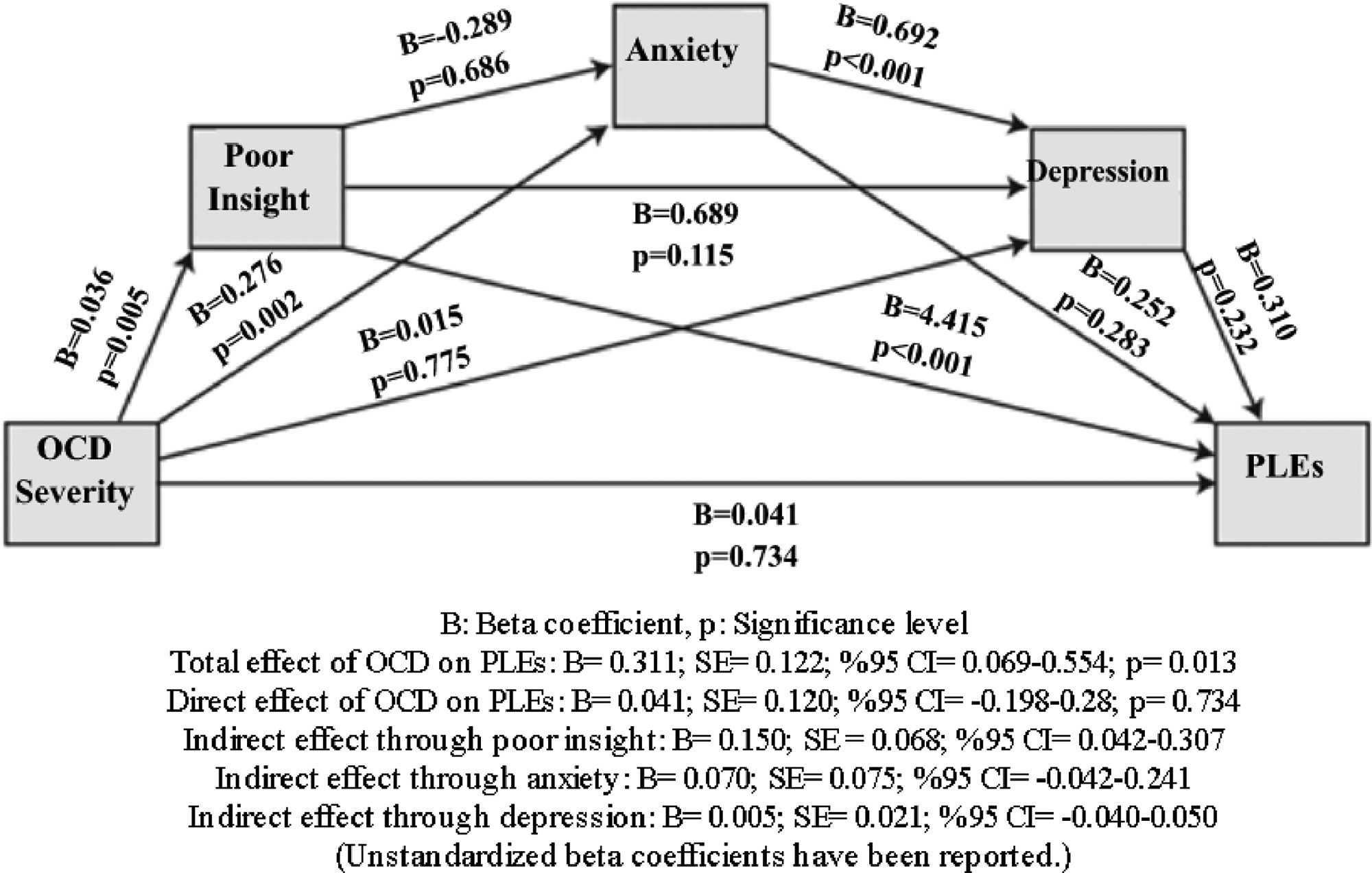

Mediation analyses were performed to examine the factors affecting the relationship between OCD severity and PLEs. Poor insight, anxiety, and depression levels, which can be conceptualized as the linking mechanisms between OCD severity and PLEs, were included in the mediation model as mediating variables, and Process Macro model 6 (serial mediation analysis) was used. In order to test the mediation effects, the regression method based on the bootstrap method was used with the help of the Process macro application developed by Hayes57 in IBM SPSS Statistics program and 5000 resampling options were preferred. In mediation analyses made with the bootstrap method, the values in the 95% confidence interval (CI) obtained as a result of the analysis should not contain the zero value in order to support the hypothesis.58 If the effect size (K²) is close to 0.01, it is considered as a low effect, close to 0.09 as a medium effect, and close to 0.25 as a high effect.59

The significance level (p) was accepted as 0.05 for all tests.

In the calculations made with the Minitab program using the mean and standard deviation values obtained from “Self-reported psychotic-like experiences in individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder versus schizophrenia patients: Characteristics and moderation role of trait anxiety” which is the study of Bortolon and Raffard46 when the type I error is 5% and the power of the study is 95%, the number of people required to be included in each group is calculated as at least 71.

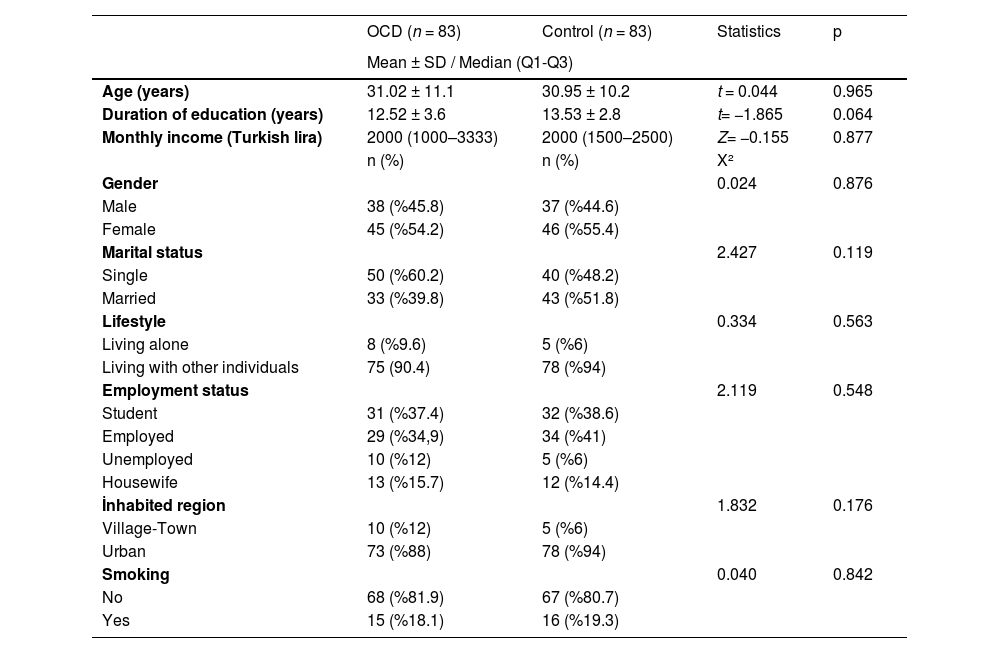

ResultsThe study population consisted of a total of 166 individuals, 83 individuals with OCD and 83 healthy individuals. There was no statistically significant difference between the sociodemographic data of both groups (Table 1).

Comparison of OCD and control groups in terms of sociodemographic characteristics.

p: Significance level, Q1: First quartile, Q3: Third quartile, n: number of samples, SD: Standard deviation, X²: Chi-square.

The mean disorder duration of the patients in the OCD group was 10.7 ± 9.3 years, and the mean duration of treatment was 7.2 ± 8 years. Of the patients, 9 (10.8%) had a suicide attempt, 13 (15.7%) had a history of inpatient treatment, and 10 (12%) had a medical illness. The mean of the total score of Y-BOCS was 20 ± 8.3, the mean of the 11th item score of Y-BOCS was 1.3 ± 1, the mean of the HAM-D score was 13 ± 5.6, and the mean of the HAM-A score was 13.4 ± 6.3.

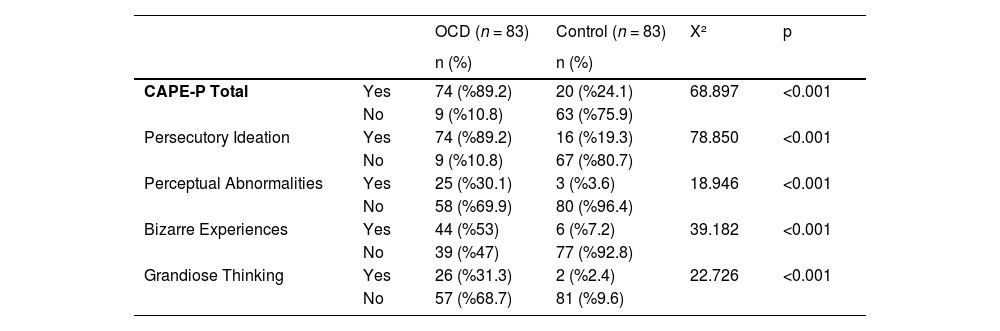

The proportion of those who approved at least one item from certain CAPE-P in the OCD and control groups is shown in Table 2. In order to make a categorical distinction as “yes/no” in this assessment, if no CAPE-P item was answered “often” or “almost constantly”, it was accepted as “no experience”. If any item was answered “often” or “almost constantly”, it was accepted as “experienced”. As a result of this comparison, more types of PLEs were detected in all areas in the OCD group.

Categorical comparison of CAPE-P in OCD and control groups.

p: Significance level, n: Number of samples, X²: Chi-square.

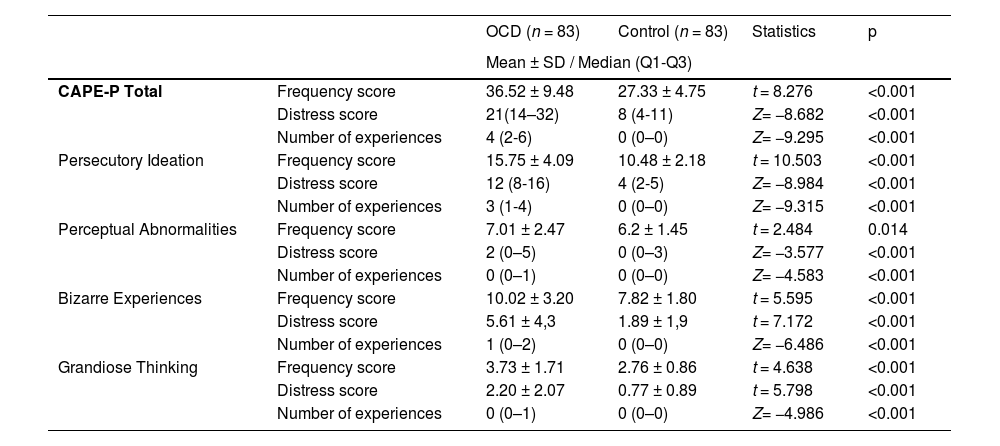

The results of the comparison of OCD and control groups in terms of the CAPE-P frequency and distress score and number of experiences are given in Table 3. The OCD group had higher score than the control group in all areas in terms of the frequency score, the distress score and the number of experiences.

Comparison of OCD and control groups in terms of CAPE-P scores.

| OCD (n = 83) | Control (n = 83) | Statistics | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD / Median (Q1-Q3) | |||||

| CAPE-P Total | Frequency score | 36.52 ± 9.48 | 27.33 ± 4.75 | t = 8.276 | <0.001 |

| Distress score | 21(14–32) | 8 (4-11) | Z= −8.682 | <0.001 | |

| Number of experiences | 4 (2-6) | 0 (0–0) | Z= −9.295 | <0.001 | |

| Persecutory Ideation | Frequency score | 15.75 ± 4.09 | 10.48 ± 2.18 | t = 10.503 | <0.001 |

| Distress score | 12 (8-16) | 4 (2-5) | Z= −8.984 | <0.001 | |

| Number of experiences | 3 (1-4) | 0 (0–0) | Z= −9.315 | <0.001 | |

| Perceptual Abnormalities | Frequency score | 7.01 ± 2.47 | 6.2 ± 1.45 | t = 2.484 | 0.014 |

| Distress score | 2 (0–5) | 0 (0–3) | Z= −3.577 | <0.001 | |

| Number of experiences | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–0) | Z= −4.583 | <0.001 | |

| Bizarre Experiences | Frequency score | 10.02 ± 3.20 | 7.82 ± 1.80 | t = 5.595 | <0.001 |

| Distress score | 5.61 ± 4,3 | 1.89 ± 1,9 | t = 7.172 | <0.001 | |

| Number of experiences | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–0) | Z= −6.486 | <0.001 | |

| Grandiose Thinking | Frequency score | 3.73 ± 1.71 | 2.76 ± 0.86 | t = 4.638 | <0.001 |

| Distress score | 2.20 ± 2.07 | 0.77 ± 0.89 | t = 5.798 | <0.001 | |

| Number of experiences | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–0) | Z= −4.986 | <0.001 | |

p: Significance level, Q1: First quartile, Q3: Third quartile, n: number of samples, SD: Standard deviation.

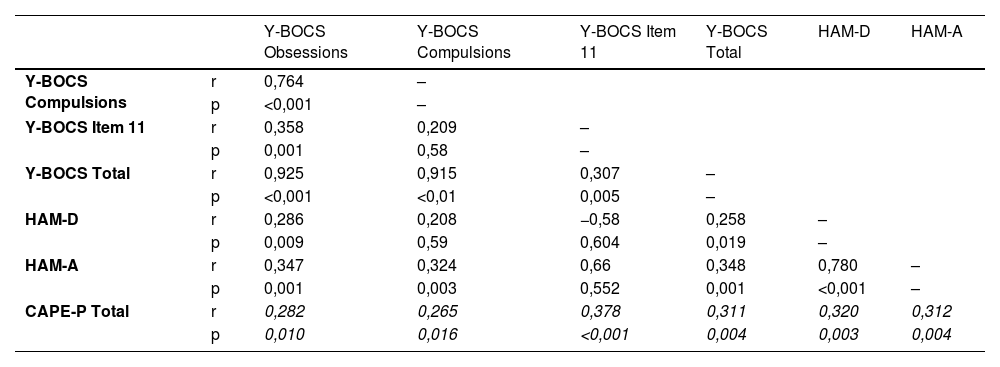

Weak positive correlations were found between CAPE-P score and Y-BOCS total, Y-BOCS insight, HAM-D and HAM-A scores (Table 4).

Correlation of clinical scales with CAPE-P score in the OCD group.

p: significance level, r: correlation coefficient.

Values written in italics were determined by Spearman correlation analysis.

The serial mediation model assumes that mediators affect each other causally. Since three mediating variables (poor insight, anxiety, depression) were used, six different causal sequences were formed. In order to show the mediating effect of poor insight, anxiety and depression levels in the relationship between OCD severity and PLEs, the model formed as a chain of poor insight, anxiety and depression, respectively, is visualized in Fig. 1. Whether OCD severity has an indirect effect on PLEs was determined according to 95% CI obtained by bootstrap method. In the model, it was determined that the effect of OCD severity on PLEs remained significant for poor insight, that is, poor insight mediated the relationship (B = 0.150;%95 CI= 0.042–0.307). This significant effect could not be found for anxiety (B = 0.070; 95% CI=−0.042–0.241) and depression (B = 0.005; 95% CI=−0.040–0.050). With the mediating variables included in the model, the direct effect of OCD severity on PLEs remained insignificant (B = 0.041; p = 0.734). The model explained approximately 31% of the variation in PLEs (R²= 0.311). The fully standardized effect size value (K²) of the mediating effect of poor insight is 0.131, and it can be said that this value indicates a moderate effect. Only the model formed as the chain of poor insight, anxiety, and depression has been reported, but a significant indirect effect has been found only through poor insight in all six models obtained.

DiscussionWhen the OCD group was compared with the healthy control group, no statistical difference was found between age, duration of education, monthly income, gender, marital status, lifestyle, employment status, inhabited region and smoking status. This eliminates the confounding effect of sociodemographic factors in the comparison of the two groups.

We found that the OCD group experienced more frequent experiences in the positive dimension, which includes the sub-dimensions of persecutory ideation, perceptual abnormalities, bizarre experiences, and grandiose thinking. In a study, it was reported that delusion-like experiences were found in OCD patients even after statistically adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics, traumatic events, alcohol and substance use disorders, and depressive disorders.26 Moritz and Laroi45 found in their study that all three dimensions of CAPE are more common in OCD than in healthy controls, which is consistent with our study findings. The reason for the higher incidence of PLEs in the OCD group may be that obsessions, compulsions, and psychotic symptoms are phenotypes developing on a similar etiological basis. As a matter of fact, there are similarities between OCD and psychosis in terms of some functional and structural brain abnormalities, neurotransmitter systems, clinical and demographic characteristics, and environmental etiological factors such as perinatal traumas, childhood traumas and, substance use.32-36 Detection of delusions and hallucinations in OCD patients, and more obsessive-compulsive symptoms in first-episode psychosis patients support this idea.60 In addition, attributional biases, which are a factor in the formation of obsessions and delusions, are made at different levels according to the cognitive capacity of the person and may affect the degree of the belief. Consistent with all these findings, we found a weak positive correlation between CAPE-P score and Y-BOCS total score.

Bortolon and Raffard46 reported that state anxiety had a moderating effect on the relationship between obsessive-compulsive symptom severity and delusional thoughts, while the level of depression had no moderating effect. In our study, in the mediation analysis in which anxiety, depression and insight variables were evaluated together, we found that poor insight mediated the relationship between OCD severity and CAPE-P score, that the anxiety and depression variables did not have a mediator effect, and the direct effect of the Y-BOCS total score on the CAPE-P score was not significant. These findings provide some implications: Although it is known that depression and anxiety increase PLEs, the decrease in the mediating effect of depression and anxiety when the level of insight is taken into account may actually indicate that the direct effects of depression and anxiety on PLEs may be partially, and that there are other factors in between. The fact that the direct effect of OCD severity on PLEs could not be determined in our study is consistent with the study of Bortolon and Raffard. However, our finding that this relationship is mediated by the level of insight and not by the levels of anxiety and depression provides inferences that looking only at the level of depression and anxiety may cause a deficiency when evaluating PLEs in OCD, and that insight is a very important factor for PLEs and has a strong effect on the symptoms in psychiatric disorders.

We found that poor insight, which is an important factor in OCD, was positively weakly correlated with CAPE-P scores. The level of insight can be expected to become delusional when the loss of insight deepens as part of reality testing. It is known that OCD patients with poor insight share more similar characteristics with the schizophrenia group than those with good insight.(31 As far as we know, the increase in the frequency of PLEs as the level of impaired insight increases in OCD has not been included in the previous literature, so our findings provide new contributions to this field. This finding is an expected finding in terms of the similar nature of delusions and impaired insight in reality testing. The higher incidence of PLEs in individuals with OCD compared to the healthy control group may be a result of poor insight in OCD patients and cognitive deficits that may cause poor insight.

Our findings contribute to the idea that obsessions and delusions take place on a continuum, but longitudinal studies including individuals with a diagnosis of psychotic disorder are needed to strengthen the evidence.

Some studies have found the prevalence of PLEs greater than 60% in young adults.61 In a study conducted in Tunisia in 2020 with healthy individuals, the mean CAPE-P score was found to be 36.1 ± 8, the prevalence of persecutory ideation was 96.6%, the prevalence of magical thoughts was 95.2%, the prevalence of bizarre experiences was 93.5%, and the prevalence of perceptual abnormalities was 53.3%.62 In a study conducted with adolescents in Spain, the mean CAPE-P score was found to be 31.8 ± 7.2. In this study, 98.3% of the participants answered positively to at least one CAPE-P item. 39% of respondents reported that some positive experiences almost always occur.6 In our study, the rate of healthy individuals who reported at least one CAPE-P item as "often" or "almost always" was found to be 24.1%, with a mean CAPE-P score of 27.33 ± 4.75. Our findings are similar to epidemiological data, but there are some differences in terms of prevalence. Studies that found a high incidence of PLEs in the general population accepted at least the “sometimes” option in CAPE for the presence of PLEs. In our study, the presence of PLEs was accepted by reporting the response as "often" or "almost always". In addition, the compatibility of PLEs with sociocultural characteristics in some regions may cause different prevalence of PLEs.

The fact that PLEs are present in the general population with a lower degree of belief, less impairment in functionality and independent of any psychiatric disease provides support for the idea of phenomenological continuity of psychosis. It can be argued that all psychological phenomena do not have a categorically natural distinction and become visible to varying degrees.

Strengths and limitationsOne of the strengths of the study is that it is the first study to examine the relationship between PLEs in OCD and OCD severity, level of insight, anxiety and depression levels. Although it is known that PLEs are also found in the general population and other psychiatric diseases apart from psychotic disorders, studies on OCD are very few, and our study contributes to this field. Studies in this field and the findings obtained may contribute to a better understanding of the nature of psychiatric diseases and, therefore, their treatment. In addition, the other strengths of our study are that the patient and control groups did not differ statistically in terms of sociodemographic characteristics and the use of mediation analysis.

One of the limitations of the study is that it is cross-sectional. Since all parameters are evaluated cross-sectionally, a causal relationship cannot be mentioned. The fact that the self-report scales used were filled according to the statements of the participants affects the objectivity of the data. The fact that the individuals in the OCD group consisted only of patients who applied to the clinic makes it difficult to generalize the study results to all OCD patients. Moreover, we did not consider the role of other potentially relevant variables: age of OCD onset (childhood or adult), family history of psychosis, history of traumatic events during childhood or adulthood, comorbidity with other psychiatric or somatic disorders, personality traits, or the type of pharmacological treatment received. We do not have any data about punctual substance use, which may have a crucial role in psychotic experiences. In addition, evaluating the level of insight in OCD patients only according to the 11th item of Y-BOCS is among the limitations of the study. We recommend using multidimensional scales to assess insight in OCD in future studies.

ConclusionsThe results of our study show that PLEs are more common in OCD patients than healthy individuals, that CAPE-P scores in OCD patients and the level of insight, OCD severity, depression and anxiety levels are correlated, and that the level of insight mediates the relationship between OCD severity and PLEs, thus revealing the determinant of the level of insight on PLEs. These results are compatible with studies on psychosis continuity and provide support in this regard. It also emphasizes the importance of the dimensional approach in psychiatry. It is essential to be aware of the fact that PLEs can be present in all individuals and that PLEs vary quantitatively, both in terms of classification of psychiatric disorders and treatment interventions.

Future longitudinal studies with larger samples, different variables, and different patient groups (for example, psychotic disorders) will guide us in this regard and contribute to our better understanding of the phenomenon of psychosis.

Obsessive-compulsive symptoms and OCD in psychotic disorders are frequently researched topics. However, studies investigating psychotic symptoms in OCD have found relatively little space in the literature. Examination of PLEs and associated factors in OCD may provide additional information about the etiology and the phenomenology of the disorder and the determination of disorder severity.

Ethical considerationsThe individuals participating in the research were informed about it, and their written consent was obtained. Approval for the research was obtained from the Ondokuz Mayıs University Clinical Research Ethics Committee with decision number 2020/706. The research data were collected between December 2020 and December 2021.

Funding statementNo funding was received for this manuscript.

The authors declare no actual or potential conflicts of interest related to this study.

All authors solemnly declare that no financial support has been from any individual or company for the submitted work. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.